Siddhaṃ script

Siddhaṃ (also Siddhāṃ[8]), also known in its later evolved form as Siddhamātṛkā,[9] is a medieval Brahmic abugida, derived from the Gupta script and ancestral to the Nāgarī, Assamese, Bengali, Tirhuta, Odia, Meitei and Nepalese scripts.[10]

| Siddhaṃ 𑖭𑖰𑖟𑖿𑖠𑖽 | |

|---|---|

The word Siddhaṃ in the Siddhaṃ script | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Sanskrit |

Time period | c. late 6th century[1] – c. 1200 CE [2] |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | |

Sister systems | Śāradā,[3][4][6] Tibetan script[5][6] |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Sidd, 302 |

Unicode alias | Siddham |

| U+11580–U+115FF Final Accepted Script Proposal | |

| |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

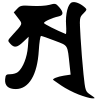

The word Siddhaṃ means "accomplished" or "perfected" in Sanskrit. The script received its name from the practice of writing Siddhaṃ, or Siddhaṃ astu (may there be perfection), at the head of documents. Other names for the script include bonji (Japanese: 梵字) lit. "Brahma's characters" and "Sanskrit script" and Chinese: 悉曇文字; pinyin: Xītán wénzi lit. "Siddhaṃ script".

Siddhaṃ is an abugida rather than an alphabet, as each character indicates a syllable, including a consonant and (possibly) a vowel. If the vowel sound is not explicitly indicated, the short 'a' is assumed. Diacritic marks are used to indicate other vowels, as well as the anusvara and visarga. A virama can be used to indicate that the consonant letter stands alone with no vowel, which sometimes happens at the end of Sanskrit words.

History

The Siddham script evolved from the Gupta Brahmi script in the late 6th century CE.[1]

Many Buddhist texts taken to China along the Silk Road were written using a version of the Siddhaṃ script. This continued to evolve, and minor variations are seen across time, and in different regions. Importantly it was used for transmitting the Buddhist tantra texts. At the time it was considered important to preserve the pronunciation of mantras, and Chinese was not suitable for writing the sounds of Sanskrit. This led to the retention of the Siddhaṃ script in East Asia. The practice of writing using Siddhaṃ survived in East Asia where Tantric Buddhism persisted.

Kūkai introduced the Siddhaṃ script to Japan when he returned from China in 806, where he studied Sanskrit with Nalanda-trained monks including one known as Prajñā (Chinese: 般若三藏; pinyin: Bōrě Sāncáng, 734–c. 810). By the time Kūkai learned this script, the trading and pilgrimage routes over land to India had been closed by the expanding Abbasid Caliphate.[12]

In Japan, the writing of mantras and copying/reading of sutras using the Siddhaṃ script is still practiced in the esoteric schools of Shingon Buddhism and Tendai as well as in the syncretic sect of Shugendō. The characters are known as shittan (悉曇) or bonji (梵字, Chinese: Fànzì). The Taishō Tripiṭaka version of the Chinese Buddhist canon preserves the Siddhaṃ characters for most mantras, and Korean Buddhists still write bījas in a modified form of Siddhaṃ. A recent innovation is the writing of Japanese language slogans on T-shirts using Bonji. Japanese Siddhaṃ has evolved from the original script used to write sūtras and is now somewhat different from the ancient script.[13][14][15]

It is typical to see Siddhaṃ written with a brush, as with Chinese writing; it is also written with a bamboo pen. In Japan, a special brush called a bokuhitsu (朴筆, Cantonese: pokbat) is used for formal Siddhaṃ calligraphy. The informal style is known as "fude" (筆, Cantonese: "moubat").

In the middle of the 9th century, China experienced a series of purges of "foreign religions", thus cutting Japan off from the sources of Siddhaṃ texts. In time, other scripts, particularly Devanagari, replaced Siddhaṃ in India, while Siddhaṃ evolved to become the Assamese, Bengali, Tirhuta, Odia, Nepalese and Meitei scripts in the eastern and northeastern regions of South Asia, leaving East Asia as the only region where Siddhaṃ is still used.

A northeastern derivative of Siddhaṃ emerged in ancient India around the 10th century CE, called Gaudi or Proto-Bengali which became the ancestor of Eastern Nagari scripts, eventually becoming the forerunner of the Bengali script.[16][17]

There were special forms of Siddhaṃ used in Korea that varied significantly from those used in China and Japan, and there is evidence that Siddhaṃ was written in Central Asia, as well, by the early 7th century.

As was done with Chinese characters, Japanese Buddhist scholars sometimes created multiple characters with the same phonological value to add meaning to Siddhaṃ characters. This practice, in effect, represents a 'blend' of the Chinese style of writing and the Indian style of writing and allows Sanskrit texts in Siddhaṃ to be differentially interpreted as they are read, as was done with Chinese characters that the Japanese had adopted. This led to multiple variants of the same characters.[18]

With regards to directionality, Siddhaṃ texts were usually read from left-to-right then top-to-bottom, as with Indic languages, but occasionally they were written in the traditional Chinese style, from top-to-bottom then right-to-left. Bilingual Siddhaṃ-Japanese texts show the manuscript turned 90 degrees clockwise and the Japanese is written from top-to-bottom, as is typical of Japanese, and then the manuscript is turned back again, and the Siddhaṃ writing is continued from left-to-right (the resulting Japanese characters look sideways).

Over time, additional markings were developed, including punctuation marks, head marks, repetition marks, end marks, special ligatures to combine conjuncts and rarely to combine syllables, and several ornaments of the scribe's choice, which are not currently encoded. The nuqta is also used in some modern Siddhaṃ texts.

The script

Vowels

Independent form Romanized As diacritic with

Independent form Romanized As diacritic with

a

ā

i

ī

u

ū

e

ai

o

au

aṃ

aḥ

Independent form Romanized As diacritic with

Independent form Romanized As diacritic with

ṛ

ṝ

ḷ

ḹ

Alternative forms  ā

ā i

i i

i ī

ī ī

ī u

u ū

ū o

o au

au aṃ

aṃ

Consonants

Stop Approximant Fricative Tenuis Aspirated Voiced Breathy voiced Nasal Glottal  h

hVelar  k

k kh

kh g

g gh

gh ṅ

ṅPalatal  c

c ch

ch j

j jh

jh ñ

ñ y

y ś

śRetroflex  ṭ

ṭ ṭh

ṭh ḍ

ḍ ḍh

ḍh ṇ

ṇ r

r ṣ

ṣDental  t

t th

th d

d dh

dh n

n l

l s

sBilabial  p

p ph

ph b

b bh

bh m

mLabiodental  v

v

Conjuncts in alphabet  kṣ

kṣ llaṃ

llaṃ

Alternative forms  ch

ch j

j ñ

ñ ṭ

ṭ ṭh

ṭh ḍh

ḍh ḍh

ḍh ṇ

ṇ ṇ

ṇ th

th th

th dh

dh n

n m

m ś

ś ś

ś v

v

Conjuncts

kkṣ -ya -ra -la -va -ma -na  k

k kya

kya kra

kra kla

kla kva

kva kma

kma kna

kna rk

rk rkya

rkya rkra

rkra rkla

rkla rkva

rkva rkma

rkma rkna

rkna kh

khtotal 68 rows.

- ↑ The combinations that contain adjoining duplicate letters should be deleted in this table.

ṅka

ṅka ṅkha

ṅkha ṅga

ṅga ṅgha

ṅgha ñca

ñca ñcha

ñcha ñja

ñja ñjha

ñjha ṇṭa

ṇṭa ṇṭha

ṇṭha ṇḍa

ṇḍa ṇḍha

ṇḍha nta

nta ntha

ntha nda

nda ndha

ndha mpa

mpa mpha

mpha mba

mba mbha

mbha

ṅya

ṅya ṅra

ṅra ṅla

ṅla ṅva

ṅva ṅśa

ṅśa ṅṣa

ṅṣa ṅsa

ṅsa ṅha

ṅha ṅkṣa

ṅkṣa

ska

ska skha

skha dga

dga dgha

dgha ṅktra

ṅktra vca/bca

vca/bca vcha/bcha

vcha/bcha vja/bja

vja/bja vjha/bjha

vjha/bjha jña

jña ṣṭa

ṣṭa ṣṭha

ṣṭha dḍa

dḍa dḍha

dḍha ṣṇa

ṣṇa sta

sta stha

stha vda/bda

vda/bda vdha/bdha

vdha/bdha rtsna

rtsna spa

spa spha

spha dba

dba dbha

dbha rkṣma

rkṣma

rkṣvya

rkṣvya rkṣvrya

rkṣvrya lta

lta tkva

tkva ṭśa

ṭśa ṭṣa

ṭṣa sha

sha bkṣa

bkṣa

pta

pta ṭka

ṭka dsva

dsva ṭṣchra

ṭṣchra

jja

jja ṭṭa

ṭṭa ṇṇa

ṇṇa tta

tta nna

nna mma

mma lla

lla vva

vva

- Alternative forms of conjuncts that contain ṇ.

ṇṭa

ṇṭa ṇṭha

ṇṭha ṇḍa

ṇḍa ṇḍha

ṇḍha

ṛ syllables

kṛ

kṛ khṛ

khṛ gṛ

gṛ ghṛ

ghṛ ṅṛ

ṅṛ cṛ

cṛ chṛ

chṛ jṛ

jṛ jhṛ

jhṛ ñṛ

ñṛ

Some sample syllables

rka

rka rkā

rkā rki

rki rkī

rkī rku

rku rkū

rkū rke

rke rkai

rkai rko

rko rkau

rkau rkaṃ

rkaṃ rkaḥ

rkaḥ ṅka

ṅka ṅkā

ṅkā ṅki

ṅki ṅkī

ṅkī ṅku

ṅku ṅkū

ṅkū ṅke

ṅke ṅkai

ṅkai ṅko

ṅko ṅkau

ṅkau ṅkaṃ

ṅkaṃ ṅkaḥ

ṅkaḥ

Siddhaṃ fonts

Siddhaṃ is still largely a hand written script. Some efforts have been made to create computer fonts, though to date none of these are capable of reproducing all of the Siddhaṃ conjunct consonants. Notably, the Chinese Buddhist Electronic Texts Association has created a Siddhaṃ font for their electronic version of the Taisho Tripiṭaka, though this does not contain all possible conjuncts. The software Mojikyo also contains fonts for Siddhaṃ, but split Siddhaṃ in different blocks and requires multiple fonts to render a single document.

A Siddhaṃ input system which relies on the CBETA font Siddhamkey 3.0 has been produced.

Unicode

Siddhaṃ script was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0.

The Unicode block for Siddhaṃ is U+11580–U+115FF:

| Siddham[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1158x | 𑖀 | 𑖁 | 𑖂 | 𑖃 | 𑖄 | 𑖅 | 𑖆 | 𑖇 | 𑖈 | 𑖉 | 𑖊 | 𑖋 | 𑖌 | 𑖍 | 𑖎 | 𑖏 |

| U+1159x | 𑖐 | 𑖑 | 𑖒 | 𑖓 | 𑖔 | 𑖕 | 𑖖 | 𑖗 | 𑖘 | 𑖙 | 𑖚 | 𑖛 | 𑖜 | 𑖝 | 𑖞 | 𑖟 |

| U+115Ax | 𑖠 | 𑖡 | 𑖢 | 𑖣 | 𑖤 | 𑖥 | 𑖦 | 𑖧 | 𑖨 | 𑖩 | 𑖪 | 𑖫 | 𑖬 | 𑖭 | 𑖮 | 𑖯 |

| U+115Bx | 𑖰 | 𑖱 | 𑖲 | 𑖳 | 𑖴 | 𑖵 | 𑖸 | 𑖹 | 𑖺 | 𑖻 | 𑖼 | 𑖽 | 𑖾 | 𑖿 | ||

| U+115Cx | 𑗀 | 𑗁 | 𑗂 | 𑗃 | 𑗄 | 𑗅 | 𑗆 | 𑗇 | 𑗈 | 𑗉 | 𑗊 | 𑗋 | 𑗌 | 𑗍 | 𑗎 | 𑗏 |

| U+115Dx | 𑗐 | 𑗑 | 𑗒 | 𑗓 | 𑗔 | 𑗕 | 𑗖 | 𑗗 | 𑗘 | 𑗙 | 𑗚 | 𑗛 | 𑗜 | 𑗝 | ||

| U+115Ex | ||||||||||||||||

| U+115Fx | ||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Delhi: Pearson. p. 43. ISBN 9788131716779.

- Its usage survives into the modern period for liturgical purposes in Japan and Korea.

- https://archive.org/details/epigraphyindianepigraphyrichardsalmonoup_908_D/mode/2up,p39-41

- Malatesha Joshi, R.; McBride, Catherine (11 June 2019). Handbook of Literacy in Akshara Orthography. ISBN 9783030059774.

- Daniels, P.T. (January 2008). "Writing systems of major and minor languages". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan languages. p. 143.

- Handbook of Literacy in Akshara Orthography, R. Malatesha Joshi, Catherine McBride(2019),p.27

- Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary, page 1215, col. 1 http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier/

- Rajan, Vinodh; Sharma, Shriramana (2012-06-28). "L2/12-221: Comments on naming the "Siddham" encoding" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- "Devanagari: Development, Amplification, and Standardisation". Central Hindi Directorate, Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Govt. of India. 3 April 1977. Retrieved 3 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- e-museum 2018 Ink on pattra (palmyra leaves used for writing upon) ink on paper Heart Sutra: 4.9x28.0 Dharani: 4.9x27.9/10.0x28.3 Late Gupta period/7–8th century Tokyo National Museum N-8.

- Pandey, Anshuman (2012-08-01). "N4294: Proposal to Encode the Siddham Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2.

- SM Dine, 2012, Sanskrit Beyond Text: The Use of Bonji (Siddham) in Mandala and Other Imagery in Ancient and Medieval Japan, University of Washington.

- Siddhaṃ : the perfect script.

- Buddhism guide: Shingon.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy.

- Handbook of Literacy in Akshara Orthography, R. Malatesha Joshi, Catherine McBride(2019)

- Kawabata, Taichi; Suzuki, Toshiya; Nagasaki, Kiyonori; Shimoda, Masahiro (2013-06-11). "N4407R: Proposal to Encode Variants for Siddham Script" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2.

Sources

- Bonji Taikan (梵字大鑑). (Tōkyō: Meicho Fukyūkai, 1983)

- Chaudhuri, Saroj Kumar (1998). Siddham in China and Japan, Sino-Platonic papers No. 88

- e-Museum, National Treasures & Important Cultural Properties of National Museums, Japan (2018), "Sanskrit Version of Heart Sutra and Viyaya Dharani", e-Museum

- Stevens, John. Sacred Calligraphy of the East. (Boston: Shambala, 1995.)

- Van Gulik, R.H. Siddham: An Essay on the History of Sanskrit Studies in China and Japan (New Delhi, Jayyed Press, 1981).

- Yamasaki, Taikō. Shingon: Japanese Esoteric Buddhism. (Fresno: Shingon Buddhist International Institute, 1988.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Siddham script. |

- Fonts:

- Noto Sans Siddham from the Noto fonts project

- Muktamsiddham—Free Unicode Siddham font

- ApDevaSiddham—(Japanese) Free Unicode 8.0 Siddham Font (mirror)

- Siddham alphabet on Omniglot

- Examples of Siddham mantras Chinese language website.

- Visible Mantra an extensive collection of mantras and some sūtras in Siddhaṃ script

- Bonji Siddham Character and Pronunciation

- SiddhamKey Software for inputting Siddham characters