List of languages by first written accounts

This is a list of languages arranged by the approximate dates of the oldest existing texts recording a complete sentence in the language. It does not include undeciphered scripts, though there are various claims without wide acceptance, which, if substantiated, would push backward the first attestation of certain languages. It also does not include inscriptions consisting of isolated words or names from a language. In most cases, some form of the language had already been spoken (and even written) considerably earlier than the dates of the earliest extant samples provided here.

A written record may encode a stage of a language corresponding to an earlier time, either as a result of oral tradition, or because the earliest source is a copy of an older manuscript that was lost. An oral tradition of epic poetry may typically bridge a few centuries, and in rare cases, over a millennium. An extreme case is the Vedic Sanskrit of the Rigveda: the earliest parts of this text may date to c. 1500 BC,[1] while the oldest known manuscripts date to c. 1040 AD.[2] Similarly the oldest Avestan texts, the Gathas, are believed to have been composed before 1000 BC, but the oldest Avestan manuscripts date from the 13th century AD.[3]

For languages that have developed out of a known predecessor, dates provided here follow conventional terminology. For example, Old French developed gradually out of Vulgar Latin, and the Oaths of Strasbourg (842) listed are the earliest text that is classified as "Old French".

Before 1000 BC

Writing first appeared in the Near East at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. A very limited number of languages are attested in the area from before the Bronze Age collapse and the rise of alphabetic writing:

- the Sumerian, Hurrian, Hattic and Elamite language isolates,

- Afro-Asiatic in the form of the Egyptian and Semitic languages and

- Indo-European (Anatolian languages and Mycenaean Greek).

In East Asia towards the end of the second millennium BC, the Sino-Tibetan family was represented by Old Chinese.

There are also a number of undeciphered Bronze Age records:

- Proto-Elamite script and Linear Elamite

- the Indus script (claimed to record a "Harappan language")

- Cretan hieroglyphs and Linear A (encoding a possible "Minoan language")[4][5]

- the Cypro-Minoan syllabary[6]

Earlier symbols, such as the Jiahu symbols, Vinča symbols and the marks on the Dispilio tablet, are believed to be proto-writing, rather than representations of language.

| Date | Language | Attestation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2690 BC | Egyptian | Egyptian hieroglyphs in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen (2nd Dynasty), Umm el-Qa'ab[7] | "proto-hieroglyphic" inscriptions from about 3300 BC (Naqada III; see Abydos, Egypt, Narmer Palette) |

| 26th century BC | Sumerian | Instructions of Shuruppak, the Kesh temple hymn and other cuneiform texts from Shuruppak and Abu Salabikh (Fara period)[8][9] | "proto-literate" period from about 3500 BC (see Kish tablet); administrative records at Uruk and Ur from c. 2900 BC. |

| c. 2400 BC | Canaanite | Semitic protective spells attested in an Egyptian inscription in the pyramid of Unas[10][11] | Initial attempts at deciphering the texts failed due to Egyptologists mistaking the Semitic spells for Egyptian, thus rendering them unintelligible. |

| c. 2400 BC | Akkadian | a few dozen pre-Sargonic texts from Mari and other sites in northern Babylonia[12] | Some proper names attested in Sumerian texts at Tell Harmal from about 2800 BC.[13] Fragments of the Legend of Etana at Tell Harmal c. 2600 BC.[14] |

| c. 2400 BC | Eblaite | Ebla tablets[15] | |

| c. 2250 BC | Elamite | Awan dynasty peace treaty with Naram-Sin[16][17] | |

| 21st century BC | Hurrian | temple inscription of Tish-atal in Urkesh[18] | |

| c. 1700 BC | Hittite | Anitta text in Hittite cuneiform[19] | Isolated Hittite words and names occur in Assyrian texts found at Kültepe, from the 19th century BC.[19] |

| 16th century BC | Palaic | Hittite texts CTH 751–754[20] | |

| c. 1450 BC | Mycenaean Greek | Linear B tablet archive from Knossos[21][22][23] | These are mostly administrative lists, with some complete sentences.[24] |

| c. 1400 BC | Luwian | Hieroglyphic Luwian monumental inscriptions, Cuneiform Luwian tablets in the Hattusa archives[25] | Isolated hieroglyphs appear on seals from the 18th century BC.[25] |

| c. 1400 BC | Hattic | Hittite texts CTH 725–745 | |

| c. 1300 BC | Ugaritic | tablets from Ugarit[26] | |

| c. 1200 BC | Old Chinese | oracle bone and bronze inscriptions from the reign of Wu Ding[27][28][29] |

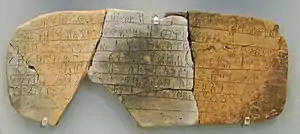

Seal impression from the tomb of Seth-Peribsen, containing the oldest known complete sentence in Egyptian, c. 2690 BC[7]

Seal impression from the tomb of Seth-Peribsen, containing the oldest known complete sentence in Egyptian, c. 2690 BC[7] Letter in Sumerian cuneiform sent by the high-priest Lu'enna, informing the king of Lagash of his son's death in battle, c. 2400 BC[30]

Letter in Sumerian cuneiform sent by the high-priest Lu'enna, informing the king of Lagash of his son's death in battle, c. 2400 BC[30]

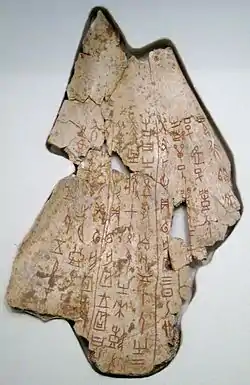

Ox scapula inscribed with three records of divinations in the reign of Wu Ding of the Chinese Shang dynasty, c. 1200 BC

Ox scapula inscribed with three records of divinations in the reign of Wu Ding of the Chinese Shang dynasty, c. 1200 BC

First millennium BC

The earliest known alphabetic inscriptions, at Serabit el-Khadim (c. 1500 BC), appear to record a Northwest Semitic language, though only one or two words have been deciphered. In the Early Iron Age, alphabetic writing spread across the Near East and southern Europe. With the emergence of the Brahmic family of scripts, languages of India are attested from after about 300 BC.

There is only fragmentary evidence for languages such as Iberian, Tartessian, Galatian and Messapian.[31] The North Picene language of the Novilara Stele from c. 600 BC has not been deciphered.[32] The few brief inscriptions in Thracian dating from the 6th and 5th centuries BC have not been conclusively deciphered.[33] The earliest examples of the Central American Isthmian script date from c. 500 BC, but a proposed decipherment remains controversial.[34]

| Date | Language | Attestation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1000 BC | Phoenician | Ahiram epitaph[35] | |

| 10th century BC | Aramaic | royal inscriptions from Aramean city-states[36] | |

| 10th century BC | Hebrew or Phoenician | Gezer calendar[37] | Paleo-Hebrew employed a slightly modified Phoenician alphabet, hence the uncertainty between which is attested to here. |

| c. 850 BC | Ammonite | Amman Citadel Inscription[38] | |

| c. 840 BC | Moabite | Mesha Stele | |

| c. 800 BC | Phrygian | Paleo-Phrygian inscriptions at Gordion[39] | |

| 8th century BC | Sabaean (Old South Arabian) | mainly boustrophedon inscriptions from Yemen[40] | |

| c. 700 BC | Etruscan | proto-Corinthian vase found at Tarquinia[41] | |

| 7th century BC | Latin | Vetusia Inscription and Fibula Praenestina[42] | |

| c. 600 BC | Lydian | inscriptions from Sardis[25] | |

| c. 600 BC | Carian | inscriptions from Caria and Egypt[25] | |

| c. 600 BC | Faliscan | Ceres inscription found at Falerii[43] | |

| early 6th century BC | Umbrian | text painted on the handle of a krater found near Tolfa[44] | |

| c. 550 BC | Taymanitic | Esk 168 and 177[45] | The Taymanitic script is mentioned in an 8th century BC document from Carchemish.[46] |

| c. 550 BC | South Picene | Warrior of Capestrano[47] | |

| mid-6th century BC | Venetic | funerary inscriptions at Este[48] | |

| c. 500 BC | Old Persian | Behistun inscription | |

| c. 500 BC | Lepontic | inscriptions CO-48 from Pristino (Como) and VA-6 from Vergiate (Varese)[49][50] | Inscriptions from the early 6th century consist of isolated names. |

| c. 300 BC | Oscan | Iovilae from Capua[51] | Coin legends date from the late 5th century BC.[52] |

| 3rd century BC | Gaulish | Transalpine Gaulish inscriptions in Massiliote Greek script[53] | |

| 3rd century BC | Volscian | Tabula Veliterna[54] | |

| c. 260 BC | Prakrit (Middle Indo-Aryan) | Edicts of Ashoka[55][56] | Pottery inscriptions from Anuradhapura have been dated c. 400 BC.[57][58] |

| early 2nd century BC | Tamil | rock inscription ARE 465/1906 at Mangulam caves, Tamil Nadu[59] (Other authors give dates from late 3rd century BC to 1st century AD.[60][61]) | 5th century BC inscriptions on potsherds found in Kodumanal, Porunthal and Palani have been claimed as Tamil-Brahmi,[62][63] but this is disputed.[64] Pottery fragments dated to the 6th century BC and inscribed with personal names have been found at Keeladi,[65] but the dating is disputed.[66] |

| 2nd century BC | Meroitic | graffiti on the temple of Amun at Dukki Gel, near Kerma[67] | |

| c. 146 BC | Numidian | Punic-Libyan Inscription at Dougga[68] | |

| c. 100 BC | Celtiberian | Botorrita plaques | |

| 1st century BC | Parthian | ostraca at Nisa and Qumis[69] | |

| 1st century BC | Sanskrit | Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana, and Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions (both near Chittorgarh)[70] | The Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman (shortly after 150 AD) is the oldest long text.[71] |

First millennium AD

From Late Antiquity, we have for the first time languages with earliest records in manuscript tradition (as opposed to epigraphy). Thus, Old Armenian is first attested in the Armenian Bible translation.

The Vimose inscriptions (2nd and 3rd centuries) in the Elder Futhark runic alphabet appear to record Proto-Norse names. Some scholars interpret the Negau helmet inscription (c. 100 BC) as a Germanic fragment.

| Date | Language | Attestation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 150 | Bactrian | Rabatak inscription | |

| c. 200 | Proto-Norse | inscription NITHIJO TAWIDE on shield grip from the Illerup Ådal weapon deposit | Single Proto-Norse words are found on the Øvre Stabu spearhead (second half of the 2nd century) and the Vimose Comb (c. 160). |

| 292 | Mayan | Stela 29 from Tikal[72] | A brief undeciphered inscription at San Bartolo is dated to the 3rd century BC.[73] |

| 312–313 | Sogdian | Ancient Letters, found near Dunhuang[74] | |

| 328 | Arabic | Namara inscription | |

| c. 350 | Ge'ez | inscriptions of Ezana of Aksum[75] | |

| c. 350 | Cham | Đông Yên Châu inscription found near Tra Kiêu[76] | |

| 4th century | Gothic | Gothic Bible, translated by Wulfila[77] | A few problematic Gothic runic inscriptions may date to the early 4th century. |

| c. 400 | Tocharian B | THT 274 and similar manuscripts[78] | Some Tocharian names and words have been found in Prakrit documents from Krorän dated c. 300.[79] |

| c. 430 | Georgian | Bir el Qutt inscriptions[80] | |

| c. 450 | Kannada | Halmidi inscription[81] | Kavirajamarga (c. 850) is the oldest literary work.[81] |

| c. 500 | Armenian | inscription at the Tekor Basilica[82] | Saint Mesrob Mashtots is traditionally held to have translated an Armenian Bible in 434. |

| c. 510 | Old Dutch | formula for freeing a serf in the Malbergse Glossen on the Salic law[83] | A word in the mid-5th century Bergakker inscription yields the oldest evidence of Dutch morphology, but there is no consensus on the interpretation of the rest of the text.[83] |

| second half of 6th century | Old High German | Pforzen buckle[84] | |

| c. 575 | Telugu | Erragudipadu inscription[81] | Telugu place names are found in Prakrit inscriptions from the 2nd century AD.[81] |

| 591 | Korean | Sinseong (新城) Stele in Namsan (Gyeongju)[85][86] | |

| 611 | Khmer | Angkor Borei inscription K. 557/600[87] | |

| c. 650 | Old Japanese | mokkan wooden tablets[88] | Poems in the Kojiki (711–712) and Nihon Shoki (720) have been transmitted in copied manuscripts. |

| c. 650–700 | Old Udi | Sinai palimpsest M13 | |

| c. 683 | Old Malay | Kedukan Bukit Inscription[89] | |

| 7th century | Tumshuqese and Khotanese Saka | manuscripts mainly from Dunhuang[90] | Some fragments of Khotanese Saka have been dated to the 5th and 6th centuries |

| 7th century | Beja | ostracon from Saqqara[91][92] | |

| late 7th century | Pyu | Hpayahtaung funeral urn inscription of kings of Sri Ksetra | |

| c. 700 | Old English | runic inscription on the Franks Casket | The Undley bracteate (5th century) and West Heslerton brooch (c. 650) have fragmentary runic inscriptions. |

| 732 | Old Turkic | Orkhon inscriptions | |

| c. 750 | Old Irish | Würzburg glosses[93] | Primitive Irish Ogham inscriptions from the 4th century consist of personal names, patronymics and/or clan names.[94][95] |

| c. 765 | Old Tibetan | Lhasa Zhol Pillar[96] | Dated entries in the Tibetan Annals begin at 650, but extant manuscripts postdate the Tibetan occupation of Dunhuang in 786.[97] |

| late 8th century | Breton | Praecepta medica (Leyden, Codex Vossianus Lat. F. 96 A)[98] | A botanical manuscript in Latin and Breton |

| c. 750–900 | Old Frisian | Westeremden yew-stick | |

| c. 800 | Old Norse | runic inscriptions | |

| 804 | Javanese | initial part of the Sukabumi inscription[99] | |

| 9th century | Malayalam | Vazhappally copper plate[100] | Ramacaritam (12th century) is the oldest literary work.[100] |

| 9th century | Old Welsh | Cadfan Stone (Tywyn 2)[101] | |

| c. 842 | Old French | Oaths of Strasbourg | |

| 882 | Balinese | dated royal inscription[102] | |

| c. 900 | Old Occitan | Tomida femina | |

| c. 959–974 | Leonese | Nodicia de Kesos | |

| c. 960–963 | Italian | Placiti Cassinesi[103] | The Veronese Riddle (c. 800) is considered a mixture of Italian and Latin.[104] |

| 986 | Khitan | Memorial for Yelü Yanning | |

| late 10th century | Old Church Slavonic | Kiev Missal | Cyril and Methodius translated religious literature from c. 862, but only later manuscripts survive. |

| late 10th century | Konkani/Marathi | inscription on the Gommateshwara statue[105] | The inscription is in Devanagari script, but the language has been disputed between Marathi and Konkani scholars.[106][107] |

1000–1500 AD

| Date | Language | Attestation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 972–1093 | Slovene | Freising manuscripts | |

| 10th century | Romansh | a sentence in the Würzburg manuscript[108] | |

| c. 1000 | Old East Slavic | Novgorod Codex[109] | |

| c. 1000 | Basque, Aragonese | Glosas Emilianenses | |

| c. 1028 | Catalan | Jurament Feudal[110] | |

| 11th century | Mozarabic | kharjas appended to Arabic and Hebrew poems[111] | Isolated words are found in glossaries from the 8th century.[112] |

| c. 1100 | Croatian | Baška tablet | |

| c. 1100 | Ossetian | Zelančuk inscription[113] | |

| c. 1106 | Irish | Lebor na hUidre ("Book of the Dun Cow") | |

| 1113 | Burmese | Myazedi inscription | |

| 1114 | Newar | palm-leaf manuscript from Uku Baha, Patan[114] | |

| 1138–1153 | Jurchen | stele in Kyongwon[115] | Aisin-Gioro Ulhicun has identified an inscription found on the Arkhara River as Jurchen and dated it to 1127. |

| 1160–1170 | Middle Dutch | Het Leven van Sint Servaes ("Life of Saint Servatius") by Heinrich von Veldeke[116] | |

| c. 1175 | Galician-Portuguese | Notícia de Fiadores[117] | The Notícia de Torto and the will of Afonso II of Portugal, dated 1214, are often cited as the first documents written in Galician-Portuguese.[118] A date prior to 1175 has been proposed for the Pacto dos Irmãos Pais.[119] |

| 1186–1190 | Serbian | Miroslav Gospel | |

| 1189 | Bosnian | Charter of Ban Kulin | |

| 1192 | Old Hungarian | Funeral Sermon and Prayer | There are isolated fragments in earlier charters such as the charter of Veszprém (c. 1000) and the charter of Tihany (1055). |

| c. 1200 | Spanish | Cantar de mio Cid | Previously the Glosas Emilianenses and the Nodicia de kesos were considered the oldest texts in Spanish; however, later analyses concluded them to be Aragonese and Leonese, respectively.[120] |

| c. 1200 | Finnic | Birch bark letter no. 292 | |

| c. 1200–1230 | Czech | founding charter of the Litoměřice chapter | |

| 1224–1225 | Mongolian | Genghis stone | |

| early 13th century | Punjabi | poetry of Fariduddin Ganjshakar | |

| early 13th century | Cornish | prophesy in the cartulary of Glasney College[121] | A 9th century gloss in De Consolatione Philosophiae by Boethius: ud rocashaas is controversially interpreted.[122][123] |

| c. 1250 | Kashmiri | Mahanayakaprakash ("Light of the supreme lord") by Shitikantha[124] | |

| c. 1270 | Old Polish | Book of Henryków | |

| 1272 | Yiddish | blessing in the Worms mahzor | |

| c. 1274 | Western Lombard | Liber di Tre Scricciur, by Bonvesin de la Riva | |

| c. 1292 | Thai | Ramkhamhaeng stele | Some scholars argue that the stele is a forgery. |

| 13th century | Tigrinya | a text of laws found in Logosarda | |

| c. 1350 | Oghuz Turkic (including Azeri and Ottoman Turkish) | Imadaddin Nasimi | |

| c. 1369 | Old Prussian | Basel Epigram[125] | |

| 1372 | Komi | Abur inscriptions | |

| early 15th century | Bengali, Assamese and other Bengali-Assamese languages | poems of Chandidas[126] | The 10th-century Charyapada are written in a language ancestral to Bengali, Assamese and Oriya.[126] |

| c. 1440 | Vietnamese | Quốc âm thi tập[127] | Isolated names in Chữ nôm date from the early 13th century. |

| 1462 | Albanian | Formula e pagëzimit, a baptismal formula in a letter of Archbishop Pal Engjëll | Some scholars interpret a few lines in the Bellifortis text (1405) as Albanian.[128] |

| c. 1470 | Finnish | single sentence in a German travel journal[129] | The first printed book in Finnish is Abckiria (1543) by Mikael Agricola. |

| c. 1470 | Maltese | Il Cantilena | |

| 1485 | Yi | bronze bell inscription in Dafang County, Guizhou[130] | |

| 15th century | Tulu | inscriptions in an adaptation of Malayam script[131] |

After 1500

| Date | Language | Attestation | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1503 | Lithuanian | hand-written Lord's Prayer, Hail Mary and Creed[132] | Katekizmas (1547) by Martynas Mažvydas was the first printed book in Lithuanian. | |

| 1517 | Belarusian | Psalter of Francysk Skaryna | ||

| 1521 | Romanian | Neacșu's Letter | Cyrillic orthographic manual of Constantin Kostentschi from 1420 documents earlier written usage.[133] Four 16th century documents, namely Codicele Voronetean, Psaltirea Scheiana, Psaltirea Hurmuzachi and Psaltirea Voroneteana, are arguably copies of 15th century originals.[134] | |

| 1530 | Latvian | Nicholas Ramm's translation of a hymn | ||

| 1535 | Estonian | Wanradt-Koell catechism | ||

| 1536 | Modern Portuguese | Grammatica da lingoagem portuguesa by Fernão de Oliveira. | by convention.[135] | |

| 1549 | Sylheti | Talib Husan by Ghulam Husan | earliest extant manuscript found using the Sylheti Nagri script.[136] | |

| 1550 | Classical Nahuatl | Doctrina cristiana en lengua española y mexicana[137] | The Breve y mas compendiosa doctrina cristiana en lengua mexicana y castellana (1539) was possibly the first printed book in the New World. No copies are known to exist today.[137] | |

| c. 1550 | Standard Dutch | Statenbijbel | The Statenbijbel is commonly accepted to be the start of Standard Dutch, but various experiments were performed around 1550 in Flanders and Brabant. Although none proved to be lasting they did create a semi-standard and many formed the base for the Statenbijbel. | |

| 1554 | Wastek | grammar by Andrés de Olmos | ||

| 1557 | Kikongo | a catechism[138] | ||

| 1561 | Ukrainian | Peresopnytsia Gospel | ||

| 1593 | Tagalog | Doctrina Cristiana | ||

| c. 1600 | Classical Quechua | Huarochirí Manuscript by a writer identified only as "Thomás"[139] | Paraphrased and annotated by Francisco de Ávila in 1608. | |

| 1600 | Buginese | |||

| c. 1610 | Manx | Book of Common Prayer[140] | ||

| 1619 | Pite Sami | primer and missal by Nicolaus Andreaus[141] | Early literary works were mainly based on dialects underlying modern Ume Sami and Pite Sami. First grammar and dictionary in 1738. | |

| 1638 | Ternate | treaty with Dutch governor[142] | ||

| 1639 | Guarani | Tesoro de la lengua guaraní by Antonio Ruíz de Montoya | ||

| c. 1650 | Ubykh, Abkhaz, Adyghe and Mingrelian | Travel Book of Evliya Çelebi[143] | ||

| 1651 | Pashto | copy of Xayru 'l-bayān in the library of the University of Tübingen[144] | The Pata Khazana, purporting to date from the 8th century, is considered by most scholars to be a forgery.[144] | |

| 1663 | Massachusett | Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God | Also known as the Eliot Indian Bible or the Algonquian Bible | |

| 1693 | Tunisian Arabic | copy of a Tunisian poem written by Sheykh Hassan el-Karray [145] | Before 1700, lyrics of songs were not written in Tunisian Arabic but in Classical Arabic.[145] | |

| c. 1695 | Seri | grammar and vocabulary compiled by Adamo Gilg | No longer known to exist.[146] | |

| 17th century | Hausa | Riwayar Annabi Musa by Abdallah Suka[147] | ||

| 18th century | Língua Geral of São Paulo | Vocabulário da Língua Geral dos Índios das Américas (anonymous)[148] | Another source is the dictionary by Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1867) and the vocabulary (1936) by José Joaquim Machado de Oliveira. The language is now extinct. | |

| 1711 | Swahili | letters written in Kilwa[149] | ||

| 1728 | Northern Sami | Catechism | An early wordlist was published in 1589 by Richard Hakluyt. First grammar in 1743 | |

| 1736 | Greenlandic | Grönländische Grammatica by Paul Egede[150] | A poor-quality wordlist was recorded by John Davis in 1586.[151] | |

| 1743 | Chinese Pidgin English | sentence recorded in Macau by George Anson[152] | ||

| 1757 | Haitian Creole | Lisette quitté la plaine by Duvivier de la Mahautière[153][154] | ||

| 1788 | Sydney language | notebooks of William Dawes[155][156] | ||

| 1795 | Afrikaans | doggerel verses[157] | ||

| 1800 | Inuktitut | "Eskimo Grammar" by Moravian missionaries[150] | A list of 17 words was recorded in 1576 by Christopher Hall, an assistant to Martin Frobisher.[150][151] | |

| 1806 | Tswana | Heinrich Lictenstein – Upon the Language of the Beetjuana | The first complete Bible translation was published in 1857 by Robert Moffat. | |

| 1819 | Cherokee | Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary | ||

| 1820 | Maori | grammar by Thomas Kendall and Samuel Lee | Kendal began compiling wordlists in 1814. | |

| 1820 | Aleut | description by Rasmus Rask | A short word list was collected by James King in 1778. | |

| 1823 | Xhosa | John Bennie's Xhosa reading sheet | Complete Bible translation 1859 | |

| c. 1833 | Vai | Vai syllabary created by Momolu Duwalu Bukele. | ||

| 1833 | Sotho | reduced to writing by French missionaries Casalis and Arbousset | First grammar book 1841 and complete Bible translation 1881 | |

| 1837 | Zulu | Incwadi Yokuqala Yabafundayo | First grammar book 1859 and complete Bible translation 1883 | |

| 1839 | Lule Sami | pamphlet by Lars Levi Laestadius | Dictionary and grammar by Karl Bernhard Wiklund in 1890-1891 | |

| 1845 | Santali | A Santali Primer by Jeremiah Phillips[158] | ||

| 1851 | Sakha (Yakut) | Über die Sprache der Jakuten, a grammar by Otto von Böhtlingk | Wordlists were included in Noord en Oost Tartarije (1692) by Nicolaas Witsen and Das Nord-und Ostliche Theil von Europa und Asia (1730) by Philip Johan von Strahlenberg. | |

| 1854 | Inari Sami | grammar by Elias Lönnrot | Primer and catechism published in 1859. | |

| 1856 | Gamilaraay | articles by William Ridley[159] | Basic vocabulary collected by Thomas Mitchell in 1832. | |

| 1872 | Venda | reduced to writing by the Berlin Missionaries | First complete Bible translation 1936 | |

| 1878 | Kildin Sami | Gospel of Matthew | ||

| 1882 | Mirandese | O dialecto mirandez by José Leite de Vasconcelos[160] | The same author also published the first book written in Mirandese: Flores mirandezas (1884)[161] | |

| 1884 | Skolt Sami | Gospel of Matthew in Cyrillic | ||

| 1885 | Carrier | Barkerville Jail Text, written in pencil on a board in the then recently created Carrier syllabics | Although the first known text by native speakers dates to 1885, the first record of the language is a list of words recorded in 1793 by Alexander MacKenzie. | |

| 1885 | Motu | grammar by W.G. Lawes | ||

| 1886 | Guugu Yimidhirr | notes by Johann Flierl, Wilhelm Poland and Georg Schwarz, culminating in Walter Roth's The Structure of the Koko Yimidir Language in 1901.[162][163] | A list of 61 words recorded in 1770 by James Cook and Joseph Banks was the first written record of an Australian language.[164] | |

| 1891 | Galela | grammatical sketch by M.J. van Baarda[165] | ||

| 1893 | Oromo | translation of the New Testament by Onesimos Nesib, assisted by Aster Ganno | ||

| 1903 | Lingala | grammar by Egide de Boeck | ||

| 1905 | Istro-Romanian | Calindaru lu rumeri din Istrie by Andrei Glavina and Constantin Diculescu[166] | Compilation of Istro-Romanian popular words, proverbs and stories.[166] | |

| c. 1940 | Kamoro | materials by Peter Drabbe[165] | A Kamoro wordlist recorded in 1828 by Modera and Müller, passengers on a Dutch ship, is the oldest record of any of the non-Austronesian languages of New Guinea.[165][167] | |

| 1968 | Southern Ndebele | small booklet published with praises of their kings and a little history | A translation of the New Testament of the Bible was completed in 1986; translation of the Old Testament is ongoing. | |

| 1984 | Gooniyandi | survey by William McGregor[168] |

By family

Attestation by major language family:

- Afro-Asiatic: since about the 27th century BC

- Hurro-Urartian: c. 21st century BC

- Indo-European: since about the 17th century BC

- 17th century BC: Anatolian (Hittite)

- 15th century BC: Greek

- 7th century BC: Italic (Latin)

- 6th century BC: Celtic (Lepontic)

- c. 500 BC: Indo-Iranian (Old Persian)

- 4th century AD: Germanic (Gothic)

- 10th century AD: Balto-Slavic (Old Church Slavonic)

- Sino-Tibetan: c. 1200 BC

- c. 1200 BC: Old Chinese

- 8th century AD: Tibeto-Burman (Tibetan)

- Dravidian: c. 200 BC (Tamil)

- Mayan: 3rd century AD

- Austronesian: 4th century AD (Cham)

- South Caucasian: 5th century (Georgian)

- Northeast Caucasian: 7th century (Udi)

- Austroasiatic: 7th century (Khmer)

- Turkic: 8th century (Old Turkic)

- Japonic: 8th century

- Nilo-Saharan: 8th century (Old Nubian)

- Basque: c. 1000

- Uralic: 12th century

- Mongolic: 13th century (Possibly related Khitan language: 10th century)

- Kra–Dai: 13th century (Thai)

- Uto-Aztecan: 16th century (Classical Nahuatl)

- Quechuan: 16th century

- Niger–Congo (Bantu): 16th century (Kikongo)

- Northwest Caucasian: 17th century (Abkhaz, Adyghe, Ubykh)

- Indigenous Australian languages: 18th century

- Iroquoian: 19th century (Cherokee)

- Hmong-Mien: 20th century

Constructed languages

| Date | Language | Attestation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1879 | Volapük | created by Johann Martin Schleyer | |

| 1887 | Esperanto | Unua Libro | created by L. L. Zamenhof |

| 1907 | Ido | based on Esperanto | |

| 1917 | Quenya | created by J. R. R. Tolkien | |

| 1928 | Novial | created by Otto Jespersen | |

| 1935 | Sona | Sona, an auxiliary neutral language | created by Kenneth Searight |

| 1943 | Interglossa | Later became Glosa | created by Lancelot Hogben |

| 1951 | Interlingua | Interlingua-English Dictionary | created by the International Auxiliary Language Association |

| 1955 | Loglan | created by James Cooke Brown | |

| 1984 | Klingon | Star Trek III: The Search for Spock | created by Marc Okrand |

| 1987 | Lojban | based on Loglan, created by the Logical Language Group | |

| 2001 | Atlantean | Atlantis: The Lost Empire | created by Marc Okrand |

| 2005–6 | Na'vi | Avatar | created by Dr. Paul Frommer and James Cameron |

| 2009 | Dothraki | created by George R. R. Martin and David J. Peterson for Game of Thrones | |

| 2013 | Kiliki | Baahubali: The Beginning, Baahubali 2: The Conclusion | created by Madhan Karky for Baahubali: The Beginning |

References

- Notes

- Jamison, Stephanie W. (2008). "Sanskrit". In Woodward, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–32. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1. pp. 6–7.

- Witzel, Michael (1997). "The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools : The Social and Political Milieu" (PDF). In Witzel, Michael (ed.). Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies. pp. 257–348. ISBN 978-1-888789-03-4. p. 259.

- Hale, Mark (2008). "Avestan". In Woodward, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–122. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1.

- Woodard (2008), p. 2.

- "Linear A – Undeciphered Writing System of the Minoans". Archaeology.about.com. 2013-07-13. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- Woodard (2008), p. 3.

- Allen, James P. (2003). The Ancient Egyptian Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-107-66467-8.

- Hayes, John (1990). A Manual of Sumerian: Grammar and Texts. Malibu, CA.: UNDENA. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-0-89003-197-1.

- Woods (2010), p. 87.

- "Earliest Semitic Text Revealed In Egyptian Pyramid Inscription". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- "לחשים בקדם־כנענית בכתבי הפירמידות: סקירה ראשונה של תולדות העברית באלף השלישי לפסה"נ | האקדמיה ללשון העברית". hebrew-academy.org.il (in Hebrew). 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- Hasselbach, Rebecca (2005). Sargonic Akkadian: A Historical and Comparative Study of the Syllabic Texts. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-447-05172-9.

- Andrew George, "Babylonian and Assyrian: A History of Akkadian", In: Postgate, J. N., (ed.), Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, pp. 31–71.

- Clay, Albert T. (2003). Atrahasis: An Ancient Hebrew Deluge Story. Book Tree. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-58509-228-4.

- Huehnergard, John; Woods, Christopher (2008). "Akkadian and Eblaite". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–145. ISBN 978-0-521-68497-2.

- Stolper, Matthew W. (2008). "Elamite". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–82. ISBN 978-0-521-68497-2.

- Potts, D.T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-521-56496-0.

- van Soldt, Wilfred H. (2010). "The adaptation of Cuneiform script to foreign languages". In De Voogt, Alexander J.; Finkel, Irving L. (eds.). The Idea of Writing: Play and Complexity. BRILL. pp. 117–128. ISBN 978-90-04-17446-7.

- Watkins, Calvert (2008). "Hittite". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–30. ISBN 978-0-521-68496-5.

- Melchert, H. Craig (2008). "Palaic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–45. ISBN 978-0-521-68496-5.

- Shelmerdine, Cynthia. "Where Do We Go From Here? And How Can the Linear B Tablets Help Us Get There?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Olivier (1986), pp. 377f.

- "Clay tablets inscribed with records in Linear B script". British Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-05-04. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Bennett, Emmett L. (1996). "Aegean scripts". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 125–133. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Baldi (2002), p. 30.

- Pardee, Dennis (2008). "Ugaritic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–35. ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9.

- Bagley (1999), pp. 181–182.

- Keightley (1999), pp. 235–237.

- DeFrancis, John (1989). "Chinese". Visible Speech. The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 89–121. ISBN 978-0-8248-1207-2.

- "Lettre du grand-prêtre Lu'enna". Louvre. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Woodard (2008), pp. 4, 9, 11.

- Woodard (2008), p. 4.

- Dimitrov, Peter A. (2009). Thracian Language and Greek and Thracian Epigraphy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-1-4438-1325-9.

- Robinson, Andrew (2008). Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World's Undeciphered Scripts. Thames & Hudson. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-500-51453-5.

- Cook, Edward M. (1994). "On the Linguistic Dating of the Phoenician Ahiram Inscription (KAI 1)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 53 (1): 33–36. doi:10.1086/373654. JSTOR 545356. S2CID 162039939.

- Creason, Stuart (2008). "Aramaic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 108–144. ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9.

- Silvan, Daniel (1998). "The Gezer Calendar and Northwest Semitic Linguistics". Israel Exploration Journal. 48 (1/2): 101–105. JSTOR 27926502.

- Fulco, William J. (1978). "The Ammn Citadel Inscription: A New Collation". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 230 (230): 39–43. doi:10.2307/1356612. JSTOR 1356612. S2CID 163239060.

- Brixhe, Claude (2008). "Phrygian". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–80. ISBN 978-0-521-68496-5.

- Nebes, Norbert; Stein, Peter (2008). "Ancient South Arabian". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–178. ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9.

- F. W. Walbank; A. E. Astin; M. W. Frederiksen, eds. (1990). Part 2 of The Cambridge Ancient History: The Hellenistic World. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

- Clackson, James (2011). A Companion to the Latin Language. John Wiley & Sons. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4443-4336-6.

- Bakkum, Gabriël C. L. M. (2009). The Latin dialect of the Ager Faliscus: 150 years of scholarship, Volume 1. University of Amsterdam Press. pp. 393–406. ISBN 978-90-5629-562-2.

- Wallace, Rex E. (1998). "Recent Research on Sabellian Inscriptions". Indo-European Studies Bulletin. 8 (1): 1–9. p. 4.

- Macdonald, M.C.A (2008). "Ancient North Arabian". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–224. ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9. p. 181.

- Macdonald, M.C.A (2000). "Reflections on the linguistic map of pre-Islamic Arabia" (PDF). Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 11 (1): 28–79. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2000.aae110106.x.

- Clackson, James; Horrocks, Geoffrey (2007). The Blackwell History of the Latin Language. Blackwell. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4051-6209-8.

- Wallace, Rex E. (2008). "Venetic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–140. ISBN 978-0-521-68495-8.

- Lexicon Leponticum Archived 2014-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, by David Stifter, Martin Braun and Michela Vignoli, University of Vienna.

- Stifter, David (2012). "Celtic in northern Italy: Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish" (PDF). Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- Buck, Carl Darling (1904). A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With a Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Boston: The Athenaeum Press. pp. 247–248.

- Buck (1904), p. 4.

- Eska, Joseph F. (2008). "Continental Celtic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–188. ISBN 978-0-521-68495-8.

- Baldi (2002), p. 140.

- Rogers, Henry (2004). Writing Systems. Black Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23464-7. p. 204

- Pollock (2003), p. 60.

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2006). "Inscribed pots, emerging identities". In Olivelle, Patrick (ed.). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. pp. 113–143. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1., pp. 121–122.

- Coningham, R.A.E.; Allchin, F.R.; Batt, C.M.; Lucy, D. (1996). "Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the Early Use of the Brahmi Script". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 6 (1): 73–97. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001608.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy. Harvard University Press. pp. 7, 97. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.

- Zvelebil, Kamil Veith (1992). Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature. BRILL. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-19-509984-2.

- Rajan, K. (2016). "Situating Iron Age moduments in South Asia: a textual and ethnographic approach". In Robbins Schug, Gwen; Walimbe, Subhash R. (eds.). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 310–318. ISBN 978-1-119-05548-8. p. 311.

- Rajan, K. (2014). Iron Age – Early Historic Transition in South India: an appraisal (PDF). Institute of Archaeology. p. 9.

- Falk, Harry (2014). "Owner's graffiti on pottery from Tissamaharama". Zeitschrift für Archäologie Außereuropäischer Kulturen. 6: 46, with footnote 2. Falk has criticized the Kodumanal and Porunthal claims as "particularly ill-informed"; Falk argues that some of the earliest supposed inscriptions are not Brahmi letters at all, but merely misinterpreted non-linguistic Megalithic graffiti symbols, which were used in South India for several centuries during the pre-literate era.

- Sivanantham, R.; Seran, M., eds. (2019). Keeladi: an Urban Settlement of Gangam Age on the Banks of the River Vigai (Report). Chennai: Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu. pp. 8–9, 14.

- Charuchandra, Sukanya (17 October 2019). "Experts Question Dates of Script in Tamil Nadu's Keeladi Excavation Report". The Wire.

- Rilly, Claude; de Voogt, Alex (2012). The Meroitic Language and Writing System. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-139-56053-5.

- "Frieze, Mausoleum of Ateban". British Museum. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Tafazzoli, A. (1996). "Sassanian Iran: Intellectual Life, Part One: Written Works" (PDF). In Litvinsky, B.A (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, volume 3. UNESCO. pp. 81–94. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0, page 94.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Salomon (1998), p. 89.

- Bricker, Victoria R. (2008). "Mayab". In Woodward, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. pp. 163–1922. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1.

- Saturno, William A.; Stuart, David; Beltrán, Boris (2006). "Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala" (PDF). Science. 311 (5765): 1281–1283. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1281S. doi:10.1126/science.1121745. PMID 16400112. S2CID 46351994.

- Henning, W. B. (1948). "The Date of the Sogdian Ancient Letters". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 12 (3/4): 601–615. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00083178. JSTOR 608717.

- Gragg, Gene (2008). "Ge'ez (Aksum)". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–237. ISBN 978-0-521-68497-2.

- Thurgood, Graham (1999). From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change. University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8248-2131-9.

- Jasanoff, Jay H. (2008). "Gothic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–214. ISBN 978-0-521-68495-8.

- Pan, Tao (2017). "A Glimpse into the Tocharian Vinaya Texts". In Andrews, Susan; Chen, Jinhua; Liu, Cuilan (eds.). Rules of Engagement: Medieval Traditions of Buddhist Monastic Regulation. Numata Center for Buddhist Studies. pp. 67–92. ISBN 978-3-89733428-1.

- Mallory, J.P. (2010). "Bronze Age languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Expedition. 52 (3): 44–53.

- Hewitt, B.G. (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins. p. 4. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3.

- Krishnamurti (2003), p. 23.

- Clackson, James P.T. (2008). "Classical Armenian". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–144. ISBN 978-0-521-68496-5.

- Willemyns, Roland (2013). Dutch: Biography of a Language. Oxford University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-19-932366-1.

- Düwel, Klaus (2004). "Runic". In Murdoch, Brian; Read, Malcolm Kevin (eds.). Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 121–147. ISBN 978-1-57113-199-7.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (2000). The Korean Language. SUNY Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-7914-4831-1.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-521-66189-8.

- Zakharov, Anton O. (2019). "The earliest dated Cambodian inscription K. 557/600 from Angkor Borei, Cambodia: an English translation and commentary". Vostok (Oriens) (1): 66–80. doi:10.31857/S086919080003960-3.

- Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010). A History of the Japanese Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-521-65320-6.

- Mahdi, Waruno (2005). "Old Malay". In Adelaar, Alexander; Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. (eds.). The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar. Routledge. pp. 182–201. ISBN 978-0-7007-1286-1.

- Emmerick, Ronald E. (2009). "Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian languages. Routledge. pp. 378–379. ISBN 978-0-7007-1131-4.

- Browne, Gerald (2003). Textus blemmyicus in aetatis christianae. Champaign: Stipes. ISBN 978-1-58874-275-9.

- Wedekind, Klaus (2010). "More on the Ostracon of Browne's Textus Blemmyicus". Annali dell'Università Degli Studi di Napoli l'Orientale. 70: 73–81.

- McCone, Kim (2005). A first Old Irish grammar and reader. National University of Ireland. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-901519-36-8.

- Edwards, Nancy (2006). The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-415-22000-2.

- McManus, Damien (1991). A Guide to Ogam. Maynooth, Co. Kildare: An Sagart. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-870684-17-0.

- Walter, Michael L.; Beckwith, Christopher I. (2010). "The Dating and Interpretation of the Old Tibetan Inscriptions". Central Asiatic Journal. 54 (2): 291–319. JSTOR 41928562.

- Schaeffer, Kurtis R.; Kapstein, Matthew; Tuttle, Gray, eds. (2013). Sources of Tibetan Tradition. Columbia University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-231-13599-3.

- Kerlouégan, François (1987). Le De Excidio Britanniae de Gildas. Les destinées de la culture latine dans l'île de Bretagne au VIe siècle (in French). Publications de la Sorbonne. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-2-85944-064-0.

- de Casparis, J. G. (1975). Indonesian Palaeography: A History of Writing in Indonesia from the Beginnings to C. A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Issue 1. BRILL. p. 31. ISBN 978-90-04-04172-1.

- Krishnamurti (2003), p. 22.

- Vousden, N. (2012). "St Cadfan's Church, Tywyn". Coflein. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- De Casparis, J. G. (1978). Indonesian Chronology. BRILL. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-04-05752-4.

- Geary, Patrick J. (1999). "Land, Language and Memory in Europe 700–1100". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 9: 169–184. doi:10.2307/3679398. JSTOR 3679398. p. 182.

- Indovinello Veronese (Italian) treccani.it

- Pollock (2003), p. 289.

- "Kamat's Potpourri- The origin and development of the Konkani language". www.kamat.com.

- Saradesāya, Manohararāya (2000). A History of Konkani Literature: From 1500 to 1992. ISBN 9788172016647.

- Liver, Ricarda (1999). Rätoromanisch: eine Einführung in das Bündnerromanische. Gunter Narr. p. 84. ISBN 978-3-8233-4973-0.

- Pereltsvaig, Asya; Lewis, Martin W. (2015). The Indo-European Controversy. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-107-05453-0.

- Josep Moran; Joan Anton Rabella, eds. (2001). Primers textos de la llengua catalana. Proa (Barcelona). ISBN 978-84-8437-156-4.

- Wilhelm, James J., ed. (2014). Lyrics of the Middle Ages: An Anthology. Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-135-03554-9.

- Sayahi, Lotfi (2014). Diglossia and Language Contact: Language Variation and Change in North Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-521-11936-8.

- Aronson, Howard Isaac (1992). The Non-Slavic Languages of the USSR. Chicago Linguistic Society, University of Chicago. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-914203-41-4.

- Malla, Kamal P. (1990). "The Earliest Dated Document in Newari: The Palmleaf From Ukū Bāhāh NS 235/AD 1114". Kailash. 16 (1–2): 15–26.

- Kane, Daniel (1989). The Sino-Jurchen Vocabulary of the Bureau of Interpreters. Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-933070-23-3.

- Willemyns (2013), p. 50.

- "Documentos relativos a Soeiro Pais, Urraca Mendes, sua mulher, e a Paio Soares Romeu, seu segundo filho e Notícia de Fiadores". Torre do Tombo National Archive. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- Azevedo, Milton M. (2005). Portuguese: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-521-80515-5.

- Agência Estado (May 2002). "Professor encontra primeiro texto escrito em português". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- Wolf, H.J. (1997). "las glosas emilianenses, otra vez". Revista de Filología Románica. 1 (14): 597–604. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Jenner, Henry (1904). A handbook of the Cornish language. London: David Nutt. p. 25.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick (2005). "A New Brittonic Gloss on Boethius: ud rocashaas". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 50: 77–86. ISSN 1353-0089.

- Breeze, Andrew (2007). "The Old Cornish Gloss on Boethius". Notes & Queries. 54 (4): 367–368. doi:10.1093/notesj/gjm184.

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005). A history of Indian literature, AD.500–1399: from courtly to the popular. Sahitya Akademi. p. 193. ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0.

- Baldi (2002), p. 35.

- Thompson, Hanne-Ruth (2012). Bengali. John Benjamins. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-272-3819-1.

- MacLeod, Mark W.; Nguyen, Thi Dieu (2001). Culture and customs of Vietnam. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-313-30485-9.

- Elsie, Robert (1986). "The Bellifortis Text and Early Albanian" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Balkanologie. 22 (2): 158–162.

- Wulff, Christine. "Zwei Finnische Sätze aus dem 15. Jahrhundert". Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher NF Bd. 2 (in German): 90–98.

- Zhou, Minglang; Sun, Hongkai, eds. (2004). Language Policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and Practice since 1949. Springer. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

- Bhat, D.N.S. (2015) [1998]. "Tulu". In Steever, Sanford B. (ed.). The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. pp. 158–177. ISBN 978-1-136-91164-4.

- Schmalstieg, Walter R. (1998). "The Baltic Languages". In Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo (eds.). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. pp. 454–479. ISBN 978-0-415-06449-1. page 459.

- Istoria Romaniei in Date (1971), p. 87

- Roegiest, Eugeen (2006). Vers les sources des langues romanes: un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania. ACCO. p. 136. ISBN 978-90-334-6094-4.

- Frias e Gouveia, Maria Carmen de (2005). "A categoria gramatical de género do português antigo ao português actual" (PDF). Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

- Islam, Muhammad Ashraful (2012). "Sylheti Nagri". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Schwaller, John Frederick (1973). "A Catalogue of Pre-1840 Nahuatl Works Held by The Lilly Library". The Indiana University Bookman. 11: 69–88.

- (in French) Balandier, Georges, Le royaume de Kongo du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Hachette, 1965, p. 58.

- Salomon, Frank; Urioste, George L., eds. (1991). The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion. University of Texas Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-292-73053-3.

- Russell, Paul (1995). An Introduction to the Celtic Languages. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-582-10081-7.

- Korhonen, Mikko (1988). "The history of the Lapp language". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages. Brill. pp. 264–287. ISBN 978-90-04-07741-6.

- Voorhoeve, C. L. (1994). "Contact-induced change in the non-Austronesian languages in the north Moluccas, Indonesia". In Dutton, Thomas Edward; Tryon, Darrell T. (eds.). Language Contact and Change in the Austronesian World. de Gruyter. pp. 649–674. ISBN 978-3-11-012786-7. pp. 658–659.

- Gippert, Jost (1992). "The Caucasian language material in Evliya Çelebi's 'Travel Book'" (PDF). In Hewitt, George (ed.). Caucasian Perspectives. Munich: Lincom. pp. 8–62. ISBN 978-3-92907501-4.

- MacKenzie, D.N. (1997). "The Development of the Pashto Script". In Akiner, Shirin; Sims-Williams, N. (eds.). Languages and Scripts of Central Asia. Routledge. pp. 137–143. ISBN 978-0-7286-0272-4.

- (in French) Fakhfakh, N. (2007). Le répertoire musical de la confrérie religieuse" al-Karrâriyya" de Sfax (Tunisie) (Doctoral dissertation, Paris8).

- Marlett, Stephen A. (1981). "The Structure of Seri" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Philips, John Edward (2004). "Hausa in the twentieth century: an overview" (PDF). Sudanic Africa. 15: 55–84. JSTOR 25653413.

- https://www.unicamp.br/unicamp/ju/591/registro-raro-de-lingua-paulista-e-identificado

- E. A. Alpers, Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa, London, 1975.., pp. 98–99 ; T. Vernet, "Les cités-Etats swahili et la puissance omanaise (1650–1720), Journal des Africanistes, 72(2), 2002, pp. 102–105.

- Nowak, Elke (1999). "The 'Eskimo language' of Labrador: Moravian missionaries and the description of Labrador Inuttut 1733–1891". Études/Inuit/Studies. 23 (1/2): 173–197. JSTOR 42870950.

- Nielsen, Flemming A. J. (2012). "The Earliest Greenlandic Bible: A Study of the Ur-Text from 1725". In Elliott, Scott S.; Boer, Roland (eds.). Ideology, Culture, and Translation. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 113–137. ISBN 978-1-58983-706-5.

- Baker, Philip; Mühlhäusler, Peter (1990). "From Business to Pidgin". Journal of Asian Pacific Communication. 1 (1): 87–116.

- Ayoun, Dalila, ed. (2008). Studies in French Applied Linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 230. ISBN 978-90-272-8994-0. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Jenson, Deborah, ed. (2012). Beyond the Slave Narrative: Politics, Sex, and Manuscripts in the Haitian Revolution. Liverpool University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-84631-760-6. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Troy, Jakelin (1992). "The Sydney Language Notebooks and responses to language contact in early colonial NSW" (PDF).

- "The notebooks of William Dawes on the Aboriginal language of Sydney".

- Mesthrie, Rajend, ed. (2002). Language in South Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780521791052.

- Ghosh, Arun (2008). "Sandali". In Anderson, Gregory D.S. (ed.). The Munda Languages. Routledge. pp. 11–98. ISBN 978-0-415-32890-6.

- Austin, Peter K. (2008). "The Gamilaraay (Kamilaroi) Language, northern New South Wales — A Brief History of Research" (PDF). In McGregor, William (ed.). Encountering Aboriginal languages: studies in the history of Australian linguistics. Australian National University. pp. 37–58. ISBN 978-0-85883-582-5.

- Ferreira, M. Barros. "A descoberta do mirandês – Marcos principais". Sítio de l Mirandés (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Universidade de Lisboa. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- LUSA (2015-06-20). "Portugueses e espanhóis assinam protocolo para promoção das línguas mirandesa e asturiana". Expresso (in Portuguese).

- Roth, Walther (1910). North Queensland Ethnography, Bulletin 2: The Structure of the Koko Yimidir Language. Brisbane: Government Printer.

- Haviland, John B. (1979). "Guugu Yimidhirr" (PDF). In Dixon, R. M. W.; Blake, Barry J. (eds.). Handbook of Australian Languages, Volume 1. Canberra: John Benjamins. pp. 26–181. ISBN 978-90-272-7355-0. p. 35

- Haviland, John B. (1974). "A last look at Cook's Guugu Yimidhirr word list" (PDF). Oceania. 44 (3): 216–232. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1974.tb01803.x. JSTOR 40329896.

- Voorhoeve, C.L. (1975). "A hundred years of Papuan Linguistic Research: Western New Guinea Area" (PDF). In Wurm, Stephen A. (ed.). New Guinea Area Languages and Language Study, Volume 1: Papuan Languages and the New Guinea Linguistic Scene. Australian National University. pp. 117–141.

- Curtis, Ervino (1992). "La lingua, la storia, la tradizione degli istroromeni" (in Italian). Trieste: Associazione di Amicizia Italo-Romena Decebal. pp. 6–13.

- Foley, William A. (1986). The Papuan Languages of New Guinea. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-28621-3.

- McGregor, William (1990). A Functional Grammar of Gooniyandi. John Benjamins. p. 26. ISBN 978-90-272-3025-6.

- Works cited

- Bagley, Robert (1999), "Shang Archaeology", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 124–231, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Baldi, Philip (2002), The Foundations of Latin, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017208-9.

- Keightley, David N. (1999), "The Shang: China's first historical dynasty", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 232–291, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003), The Dravidian Languages, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- Olivier, J.-P. (1986), "Cretan Writing in the Second Millennium B.C", World Archaeology, 17 (3): 377–389, doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979977.

- Pollock, Sheldon (2003), The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24500-6.

- Woodard, Roger D. (2008), "Language in ancient Europe: an introduction", in Woodard, Roger D. (ed.), The Ancient Languages of Europe, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–13, ISBN 978-0-521-68495-8.

- Woods, Christopher (ed.) (2010), Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond (PDF), Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)