Brahmic scripts

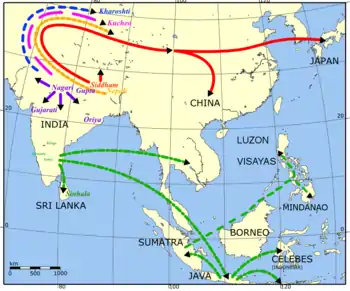

The Brahmic scripts are a family of abugida writing systems. They are used throughout the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and parts of East Asia, including Japan in the form of Siddhaṃ. They have descended from the Brahmi script of ancient India and are used by various languages in several language families in South, East and Southeast Asia: Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Mongolic, Austroasiatic, Austronesian and Tai. They were also the source of the dictionary order (gojūon) of Japanese kana.[2]

| Predominant national and selected regional or minority scripts |

|---|

|

| Alphabetical |

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

|

Ethiopic |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

History

Brahmic scripts descended from the Brahmi script. Brahmi is clearly attested from the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ashoka, who used the script for imperial edicts, but there are some claims of earlier epigraphy found on pottery in South India and Sri Lanka. The most reliable of these were short Brahmi inscriptions dated to the 4th century BC and published by Coningham et al. (1996).[3] Northern Brahmi gave rise to the Gupta script during the Gupta period, which in turn diversified into a number of cursives during the medieval period. Notable examples of such medieval scripts, developed by the 7th or 8th century, include Nagari, Siddham and Sharada.

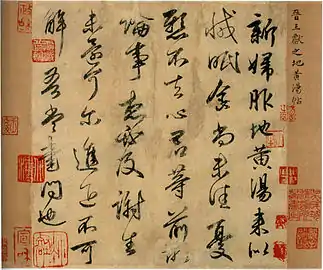

The Siddhaṃ script was especially important in Buddhism, as many sutras were written in it. The art of Siddham calligraphy survives today in Japan. The syllabic nature and dictionary order of the modern kana system of Japanese writing is believed to be descended from the Indic scripts, most likely through the spread of Buddhism.[4]

Southern Brahmi evolved into the Old Kannada, Pallava and Vatteluttu scripts, which in turn diversified into other scripts of South India and Southeast Asia.

The present Telugu script is derived from the Kannada-Telugu script, also known as "Old Kannada script", owing to its similarity to the same.[5]

A fragment of Ashoka's 6th pillar edict, in Brahmi, the ancestor of all Brahmic scripts

A fragment of Ashoka's 6th pillar edict, in Brahmi, the ancestor of all Brahmic scripts Spread of Brahmic family of scripts from India

Spread of Brahmic family of scripts from India

Characteristics

|

| Calligraphy |

|---|

Some characteristics, which are present in most but not all the scripts, are:

- Each consonant has an inherent vowel which is usually a short 'a' (in Bengali, Assamese and Odia it is a short 'ô' due to sound shifts). Other vowels are written by adding to the character. A mark, known in Sanskrit as a virama/halant, can be used to indicate the absence of an inherent vowel.

- Each vowel has two forms, an independent form when not attached to a consonant, and a dependent form, when attached to a consonant. Depending on the script, the dependent forms can be either placed to the left of, to the right of, above, below, or on both the left and the right sides of the base consonant.

- Consonants (up to 4 in Devanagari) can be combined in ligatures. Special marks are added to denote the combination of 'r' with another consonant.

- Nasalization and aspiration of a consonant's dependent vowel is also noted by separate signs.

- The alphabetical order is: vowels, velar consonants, palatal consonants, retroflex consonants, dental consonants, bilabial consonants, approximants, sibilants, and other consonants. Each consonant grouping had four stops (with all four possible values of voicing and aspiration), and a nasal consonant.

Comparison

Below are comparison charts of several of the major Indic scripts, organised on the principle that glyphs in the same column all derive from the same Brahmi glyph. Accordingly:

- The charts are not comprehensive. Glyphs may be unrepresented if they don't derive from any Brahmi character, but are later inventions.

- The pronunciations of glyphs in the same column may not be identical. The pronunciation row is only representative; the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) pronunciation is given for Sanskrit where possible, or another language if necessary.

The transliteration is indicated in ISO 15919.

Consonants

| ISO[lower-alpha 1] | ka | kha | ga | gha | ṅa | ca | cha | ja | jha | ña | ṭa | ṭha | ḍa | ḍha | ṇa | ta | tha | da | dha | na | ṉa | pa | pha | ba | bha | ma | ya | ẏa | ra | ṟa | la | ḷa | ḻa | va | śa | ṣa | sa | ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assamese | ক | খ | গ | ঘ | ঙ | চ | ছ | জ | ঝ | ঞ | ট | ঠ | ড | ঢ | ণ | ত | থ | দ | ধ | ন | প | ফ | ব | ভ | ম | য় | য | ৰ | ল | ৱ | শ | ষ | স | হ | ||||

| Bengali | ক | খ | গ | ঘ | ঙ | চ | ছ | জ | ঝ | ঞ | ট | ঠ | ড | ঢ | ণ | ত | থ | দ | ধ | ন | প | ফ | ব | ভ | ম | য় | য | র | ল | শ | ষ | স | হ | |||||

| Sylheti Nagari | ꠇ | ꠈ | ꠉ | ꠊ | ꠌ | ꠍ | ꠎ | ꠏ | ꠐ | ꠑ | ꠒ | ꠓ | ꠔ | ꠕ | ꠖ | ꠗ | ꠘ | ꠙ | ꠚ | ꠛ | ꠜ | ꠝ | ꠞ | ꠟ | ꠡ | ꠢ | ||||||||||||

| Devanagari | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | ऩ | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | य़ | र | ऱ | ल | ळ | ऴ | व | श | ष | स | ह |

| Gujarati | ક | ખ | ગ | ઘ | ઙ | ચ | છ | જ | ઝ | ઞ | ટ | ઠ | ડ | ઢ | ણ | ત | થ | દ | ધ | ન | પ | ફ | બ | ભ | મ | ય | ર | લ | ળ | વ | શ | ષ | સ | હ | ||||

| Odia | କ | ଖ | ଗ | ଘ | ଙ | ଚ | ଛ | ଜ | ଝ | ଞ | ଟ | ଠ | ଡ | ଢ | ଣ | ତ | ଥ | ଦ | ଧ | ନ | ପ | ଫ | ବ | ଭ | ମ | ୟ | ଯ | ର | ଲ | ଳ | ୱ | ଶ | ଷ | ସ | ହ | |||

| Gurmukhi | ਕ | ਖ | ਗ | ਘ | ਙ | ਚ | ਛ | ਜ | ਝ | ਞ | ਟ | ਠ | ਡ | ਢ | ਣ | ਤ | ਥ | ਦ | ਧ | ਨ | ਪ | ਫ | ਬ | ਭ | ਮ | ਯ | ਰ | ਲ | ਲ਼ | ਵ | ਸ਼ | ਸ | ਹ | |||||

| Meitei Mayek[lower-alpha 2] | ꯀ | ꯈ | ꯒ | ꯘ | ꯉ | ꯆ | ꫢ | ꯖ | ꯓ | ꫣ | ꫤ | ꫥ | ꫦ | ꫧ | ꫨ | ꯇ | ꯊ | ꯗ | ꯙ | ꯅ | ꯄ | ꯐ | ꯕ | ꯚ | ꯃ | ꯌ | ꯔ | ꯂ | ꯋ | ꫩ | ꫪ | ꯁ | ꯍ | |||||

| Tibetan | ཀ | ཁ | ག | གྷ | ང | ཅ | ཆ | ཇ | ཛྷ | ཉ | ཊ | ཋ | ཌ | ཌྷ | ཎ | ཏ | ཐ | ད | དྷ | ན | པ | ཕ | བ | བྷ | མ | ཡ | ར | ལ | ཝ | ཤ | ཥ | ས | ཧ | |||||

| Lepcha | ᰀ | ᰂ | ᰃ | ᰅ | ᰆ | ᰇ | ᰈ | ᰉ | ᱍ | ᱎ | ᱏ | ᰊ | ᰋ | ᰌ | ᰍ | ᰎ | ᰐ | ᰓ | ᰕ | ᰚ | ᰛ | ᰜ | ᰟ | ᰡ | ᰡ᰷ | ᰠ | ᰝ | |||||||||||

| Limbu | ᤁ | ᤂ | ᤃ | ᤄ | ᤅ | ᤆ | ᤇ | ᤈ | ᤉ | ᤊ | ᤋ | ᤌ | ᤍ | ᤎ | ᤏ | ᤐ | ᤑ | ᤒ | ᤓ | ᤔ | ᤕ | ᤖ | ᤗ | ᤘ | ᤙ | ᤚ | ᤛ | ᤜ | ||||||||||

| Tirhuta | 𑒏 | 𑒐 | 𑒑 | 𑒒 | 𑒓 | 𑒔 | 𑒕 | 𑒖 | 𑒗 | 𑒘 | 𑒙 | 𑒚 | 𑒛 | 𑒜 | 𑒝 | 𑒞 | 𑒟 | 𑒠 | 𑒡 | 𑒢 | 𑒣 | 𑒤 | 𑒥 | 𑒦 | 𑒧 | 𑒨 | 𑒩 | 𑒪 | 𑒬 | 𑒭 | 𑒮 | 𑒯 | ||||||

| Kaithi | 𑂍 | 𑂎 | 𑂏 | 𑂐 | 𑂑 | 𑂒 | 𑂓 | 𑂔 | 𑂕 | 𑂖 | 𑂗 | 𑂘 | 𑂙 | 𑂛 | 𑂝 | 𑂞 | 𑂟 | 𑂠 | 𑂡 | 𑂢 | 𑂣 | 𑂤 | 𑂥 | 𑂦 | 𑂧 | 𑂨 | 𑂩 | 𑂪 | 𑂫 | 𑂬 | 𑂭 | 𑂮 | 𑂯 | |||||

| Early Brahmi | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀴 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | ||||

| Middle Brahmi | 𑀴 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Late Brahmi | 𑀴 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tocharian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Telugu | క | ఖ | గ | ఘ | ఙ | చ | ఛ | జ | ఝ | ఞ | ట | ఠ | డ | ఢ | ణ | త | థ | ద | ధ | న | ప | ఫ | బ | భ | మ | య | ర | ఱ | ల | ళ | ೞ | వ | శ | ష | స | హ | ||

| Kannada | ಕ | ಖ | ಗ | ಘ | ಙ | ಚ | ಛ | ಜ | ಝ | ಞ | ಟ | ಠ | ಡ | ಢ | ಣ | ತ | ಥ | ದ | ಧ | ನ | ಪ | ಫ | ಬ | ಭ | ಮ | ಯ | ರ | ಱ | ಲ | ಳ | ೞ | ವ | ಶ | ಷ | ಸ | ಹ | ||

| Sinhala | ක | ඛ | ග | ඝ | ඞ | ච | ඡ | ජ | ඣ | ඤ | ට | ඨ | ඩ | ඪ | ණ | ත | ථ | ද | ධ | න | ප | ඵ | බ | භ | ම | ය | ර | ල | ළ | ව | ශ | ෂ | ස | හ | ||||

| Malayalam | ക | ഖ | ഗ | ഘ | ങ | ച | ഛ | ജ | ഝ | ഞ | ട | ഠ | ഡ | ഢ | ണ | ത | ഥ | ദ | ധ | ന | ഩ | പ | ഫ | ബ | ഭ | മ | യ | ര | റ | ല | ള | ഴ | വ | ശ | ഷ | സ | ഹ | |

| Grantham | 𑌕 | 𑌖 | 𑌗 | 𑌘 | 𑌙 | 𑌚 | 𑌛 | 𑌜 | 𑌝 | 𑌞 | 𑌟 | 𑌠 | 𑌡 | 𑌢 | 𑌣 | 𑌤 | 𑌥 | 𑌦 | 𑌧 | 𑌨 | 𑌪 | 𑌫 | 𑌬 | 𑌭 | 𑌮 | 𑌯 | 𑌰 | 𑌲 | 𑌳 | 𑌵 | 𑌶 | 𑌷 | 𑌸 | 𑌹 | ||||

| Tamil | க | ங | ச | ஜ | ஞ | ட | ண | த | ந | ன | ப | ம | ய | ர | ற | ல | ள | ழ | வ | ஶ | ஷ | ஸ | ஹ | |||||||||||||||

| Chakma[lower-alpha 3] | 𑄇 | 𑄈 | 𑄉 | 𑄊 | 𑄋 | 𑄌 | 𑄍 | 𑄎 | 𑄏 | 𑄐 | 𑄑 | 𑄒 | 𑄓 | 𑄔 | 𑄕 | 𑄖 | 𑄗 | 𑄘 | 𑄙 | 𑄚 | 𑄛 | 𑄜 | 𑄝 | 𑄞 | 𑄟 | 𑄠 | 𑄡 | 𑄢 | 𑄣 | 𑅄 | 𑄤 | 𑄥 | 𑄦 | |||||

| Burmese | က | ခ | ဂ | ဃ | င | စ | ဆ | ဇ | ဈ | ဉ / ည | ဋ | ဌ | ဍ | ဎ | ဏ | တ | ထ | ဒ | ဓ | န | ပ | ဖ | ဗ | ဘ | မ | ယ | ရ | ၒ | လ | ဠ | ၔ | ဝ | ၐ | ၑ | သ | ဟ | ||

| Khmer | ក | ខ | គ | ឃ | ង | ច | ឆ | ជ | ឈ | ញ | ដ | ឋ | ឌ | ឍ | ណ | ត | ថ | ទ | ធ | ន | ប | ផ | ព | ភ | ម | យ | រ | ល | ឡ | វ | ឝ | ឞ | ស | ហ | ||||

| Thai | ก | ข,ฃ[lower-alpha 4] | ค,ฅ[lower-alpha 4] | ฆ | ง | จ | ฉ | ช,ซ[lower-alpha 4] | ฌ | ญ | ฎ,[lower-alpha 4]ฏ | ฐ | ฑ | ฒ | ณ | ด,[lower-alpha 4]ต | ถ | ท | ธ | น | บ,[lower-alpha 4]ป | ผ,ฝ[lower-alpha 4] | พ,ฟ[lower-alpha 4] | ภ | ม | ย | ร | ล | ฬ | ว | ศ | ษ | ส | ห,ฮ[lower-alpha 4] | ||||

| Lao | ກ | ຂ | ຄ | ງ | ຈ | ຊ | ຕ | ຖ | ທ | ນ | ປ | ຜ | ພ | ມ | ຍ | ຣ | ລ | ວ | ສ | ຫ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cham | ꨆ | ꨇ | ꨈ | ꨉ | ꨋ | ꨌ | ꨍ | ꨎ | ꨏ | ꨑ | ꨓ | ꨔ | ꨕ | ꨖ | ꨘ | ꨚ | ꨜ | ꨝ | ꨞ | ꨠ | ꨢ | ꨣ | ꨤ | ꨥ | ꨦ | ꨧ | ꨨ | |||||||||||

| Balinese | ᬓ | ᬔ | ᬕ | ᬖ | ᬗ | ᬘ | ᬙ | ᬚ | ᬛ | ᬜ | ᬝ | ᬞ | ᬟ | ᬠ | ᬡ | ᬢ | ᬣ | ᬤ | ᬥ | ᬦ | ᬧ | ᬨ | ᬩ | ᬪ | ᬫ | ᬬ | ᬭ | ᬮ | ᬯ | ᬰ | ᬱ | ᬲ | ᬳ | |||||

| Javanese[lower-alpha 5] | ꦏ | ꦑ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦒ | ꦓ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦔ | ꦕ | ꦖ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦗ | ꦙ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦚ | ꦛ | ꦜ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦝ | ꦞ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦟ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦠ | ꦡ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦢ | ꦣ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦤ | ꦘ | ꦥ | ꦦ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦧ | ꦨ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦩ | ꦪ | ꦫ | ꦭ | ꦮ | ꦯ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦰ[lower-alpha 5] | ꦱ | ꦲ | ||||

| Sundanese | ᮊ | ᮮ | ᮌ | ᮍ | ᮎ | ᮏ | ᮑ | ᮒ | ᮓ | ᮔ | ᮕ | ᮘ | ᮽ | ᮙ | ᮚ | ᮛ | ᮜ | ᮝ | ᮯ | ᮞ | ᮠ | |||||||||||||||||

| Lontara | ᨀ | ᨁ | ᨂ | ᨌ | ᨍ | ᨎ | ᨈ | ᨉ | ᨊ | ᨄ | ᨅ | ᨆ | ᨐ | ᨑ | ᨒ | ᨓ | ᨔ | ᨕ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rejang | ꤰ | ꤱ | ꤲ | ꤹ | ꤺ | ꤻ | ꤳ | ꤴ | ꤵ | ꤶ | ꤷ | ꤸ | ꤿ | ꤽ | ꤾ | ꥀ | ꤼ | ꥁ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Batak (Toba) | ᯂ | ᯎ | ᯝ | ᯐ | ᯠ/ᯛ | ᯖ | ᯑ | ᯉ | ᯇ | ᯅ | ᯔ | ᯒ | ᯞ | ᯞ | ᯘ | ᯂ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baybayin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Buhid | ᝃ | ᝄ | ᝅ | ᝆ | ᝇ | ᝈ | ᝉ | ᝊ | ᝋ | ᝌ | ᝍ | ᝎ | ᝏ | ᝐ | ᝑ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanunuo | ᜣ | ᜤ | ᜥ | ᜦ | ᜧ | ᜨ | ᜩ | ᜪ | ᜫ | ᜬ | ᜭ | ᜮ | ᜯ | ᜰ | ᜱ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagbanwa | ᝣ | ᝤ | ᝥ | ᝦ | ᝧ | ᝨ | ᝩ | ᝪ | ᝫ | ᝬ | ᝮ | ᝯ | ᝰ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO | ka | kha | ga | gha | ṅa | ca | cha | ja | jha | ña | ṭa | ṭha | ḍa | ḍha | ṇa | ta | tha | da | dha | na | ṉa | pa | pha | ba | bha | ma | ya | ẏa | ra | ṟa | la | ḷa | ḻa | va | śa | ṣa | sa | ha |

- Notes

- This list (tries to) includes characters of same origins, not same sounds. In Bengali র is pronounced as rô but it is originally va which is still used for wa sound in Mithilakshar and modern Assamese ৱ (wabbô) was derived from middle Assamese র (wô). Compare with জ (ja) য (ya) and য় (ẏ) which are pronounced as jô, jô and yô in Bengali and zô, zô and yô in Assamese respectively. য is related to Devanagari य (ya) and it is still pronounced as "ya" in Mithilakshar. Since their sounds shifted, the dots were added to keep the original sounds.

- includes supplementary consonants not in contemporary use

- inherent vowel is ā

- Modified forms of these letters are used for, but are not restricted to, Sanskrit and Pali in the Thai script.

- Letters used in Old Javanese. They are now obsolete, but are used for honorifics in contemporary Javanese.

Vowels

Vowels are presented in their independent form on the left of each column, and in their corresponding dependent form (vowel sign) combined with the consonant k on the right. A glyph for ka is an independent consonant letter itself without any vowel sign, where the vowel a is inherent.

| ISO | a | ā | ê | ô | i | ī | u | ū | e | ē | ai | o | ō | au | r̥ | r̥̄ [lower-alpha 1] | l̥ [lower-alpha 1] | l̥̄ [lower-alpha 1] | ṁ | ḥ | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ka | ā | kā | ê | kê | ô | kô | i | ki | ī | kī | u | ku | ū | kū | e | ke | ē | kē | ai | kai | o | ko | ō | kō | au | kau | r̥ | kr̥ | r̥̄ | kr̥̄ | l̥ | kl̥ | l̥̄ | kl̥̄ | ṁ | kṁ | ḥ | kḥ | k | |

| Assamese | অ | ক | আ | কা | অ্যা | ক্যা | ই | কি | ঈ | কী | উ | কু | ঊ | কূ | এ | কে | ঐ | কৈ | অৗ | কৗ | ও | কো | ঔ | কৌ | ঋ | কৃ | ৠ | কৄ | ঌ | কৢ | ৡ | কৣ | অং | কং | অঃ | কঃ | ক্,ক্ | ||||

| Bengali | অ | ক | আ | কা | অ্যা | ক্যা | ই | কি | ঈ | কী | উ | কু | ঊ | কূ | এ | কে | ঐ | কৈ | অ | ক | ও | কো | ঔ | কৌ | ঋ | কৃ | ৠ | কৄ | ঌ | কৢ | ৡ | কৣ | অং | কং | অঃ | কঃ | ক্,ক্ | ||||

| Devanagari | अ | क | आ | का | ॲ | कॅ | ऑ | कॉ | इ | कि | ई | की | उ | कु | ऊ | कू | ऎ | कॆ | ए | के | ऐ | कै | ऒ | कॊ | ओ | को | औ | कौ | ऋ | कृ | ॠ | कॄ | ऌ | कॢ | ॡ | कॣ | अं | कं | अः | कः | क्,क् |

| Gujarati | અ | ક | આ | કા | ઇ | કિ | ઈ | કી | ઉ | કુ | ઊ | કૂ | એ | કે | ઐ | કૈ | ઓ | કો | ઔ | કૌ | ઋ | કૃ | ૠ | કૄ | ઌ | કૢ | ૡ | કૣ | અં | કં | અઃ | કઃ | ક્,ક્ | ||||||||

| Odia | ଅ | କ | ଆ | କା | ଇ | କି | ଈ | କୀ | ଉ | କୁ | ଊ | କୂ | ଏ | କେ | ଐ | କୈ | ଓ | କୋ | ଔ | କୌ | ଋ | କୃ | ୠ | କୄ | ଌ | କୢ | ୡ | କୣ | ଂ | କଂ | ଃ | କଃ | କ୍ | ||||||||

| Gurmukhi | ਅ | ਕ | ਆ | ਕਾ | ਇ | ਕਿ | ਈ | ਕੀ | ਉ | ਕੁ | ਊ | ਕੂ | ਏ | ਕੇ | ਐ | ਕੈ | ਓ | ਕੋ | ਔ | ਕੌ | ਅਂ | ਕਂ | ਅਃ | ਕਃ | ਕ੍ | ||||||||||||||||

| Meitei Mayek[lower-alpha 2] | ꯑ | ꯀ | ꯑꯥ | ꯀꯥ | ꯏ | ꯀꯤ | ꯑꫫ | ꯀꫫ | ꯎ | ꯀꯨ | ꯑꫬ | ꯀꫬ | ꯑꯦ | ꯀꯦ | ꯑꯩ | ꯀꯩ | ꯑꯣ | ꯀꯣ | ꯑꯧ | ꯀꯧ | ꯑꯪ | ꯀꯪ | ꯑꫵ | ꯀꫵ | ꯛ | ||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཨ | ཀ | ཨཱ | ཀཱ | ཨི | ཀི | ཨཱི | ཀཱི | ཨུ | ཀུ | ཨཱུ | ཀཱུ | ཨེ | ཀེ | ཨཻ | ཀཻ | ཨོ | ཀོ | ཨཽ | ཀཽ | རྀ | ཀྲྀ | རཱྀ | ཀཷ | ལྀ | ཀླྀ | ལཱྀ | ཀླཱྀ | ཨཾ | ཀཾ | ཨཿ | ཀཿ | ཀ྄ | ||||||||

| Lepcha | ᰣ | ᰀ | ᰣᰦ | ᰀᰦ | ᰣᰧ | ᰀᰧ | ᰣᰧᰶ | ᰀᰧᰶ | ᰣᰪ | ᰀᰪ | ᰣᰫ | ᰀᰫ | ᰣᰬ | ᰀᰬ | ᰣᰨ | ᰀᰨ | ᰣᰩ | ᰀᰩ | ᰣᰴ | ᰀᰴ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Limbu | ᤀ | ᤁ | ᤀᤠ | ᤁᤠ | ᤀᤡ | ᤁᤡ | ᤀᤡ᤺ | ᤁᤡ᤺ | ᤀᤢ | ᤁᤢ | ᤀ᤺ᤢ | ᤁ᤺ᤢ | ᤀᤧ | ᤁᤧ | ᤀᤣ | ᤁᤣ | ᤀᤤ | ᤁᤤ | ᤀᤨ | ᤁᤨ | ᤀᤥ | ᤁᤥ | ᤀᤦ | ᤁᤦ | ᤀᤲ | ᤁᤲ | ᤁ᤻ | ||||||||||||||

| Tirhuta | 𑒁 | 𑒏 | 𑒂 | 𑒏𑒰 | 𑒃 | 𑒏𑒱 | 𑒄 | 𑒏𑒲 | 𑒅 | 𑒏𑒳 | 𑒆 | 𑒏𑒴 | 𑒏𑒺 | 𑒋 | 𑒏𑒹 | 𑒌 | 𑒏𑒻 | 𑒏𑒽 | 𑒍 | 𑒏𑒼 | 𑒎 | 𑒏𑒾 | 𑒇 | 𑒏𑒵 | 𑒈 | 𑒏𑒶 | 𑒉 | 𑒏𑒷 | 𑒊 | 𑒏𑒸 | 𑒁𑓀 | 𑒏𑓀 | 𑒁𑓁 | 𑒏𑓁 | 𑒏𑓂 | ||||||

| Kaithi | 𑂃 | 𑂍 | 𑂄 | 𑂍𑂰 | 𑂅 | 𑂍𑂱 | 𑂆 | 𑂍𑂲 | 𑂇 | 𑂍𑂳 | 𑂈 | 𑂍𑂴 | 𑂉 | 𑂍𑂵 | 𑂊 | 𑂍𑂶 | 𑂋 | 𑂍𑂷 | 𑂌 | 𑂍𑂸 | 𑂃𑂁 | 𑂍𑂁 | 𑂃𑂂 | 𑂍𑂂 | 𑂍𑂹 | ||||||||||||||||

| Sylheti Nagari | ꠇ | ꠀ | ꠇꠣ | ꠁ | ꠇꠤ | ꠃ | ꠇꠥ | ꠄ | ꠇꠦ | ꠅꠂ | ꠇꠂ | ꠅ | ꠇꠧ | ꠀꠋ | ꠇꠋ | ꠇ꠆ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brahmi | 𑀅 | 𑀓 | 𑀆 | 𑀓𑀸 | 𑀇 | 𑀓𑀺 | 𑀈 | 𑀓𑀻 | 𑀉 | 𑀓𑀼 | 𑀊 | 𑀓𑀽 | 𑀏 | 𑀓𑁂 | 𑀐 | 𑀓𑁃 | 𑀑 | 𑀓𑁄 | 𑀒 | 𑀓𑁅 | 𑀋 | 𑀓𑀾 | 𑀌 | 𑀓𑀿 | 𑀍 | 𑀓𑁀 | 𑀎 | 𑀓𑁁 | 𑀅𑀂 | 𑀓𑀂 | 𑀅𑀃 | 𑀓𑀃 | 𑀓𑁆 | ||||||||

| Telugu | అ | క | ఆ | కా | ఇ | కి | ఈ | కీ | ఉ | కు | ఊ | కూ | ఎ | కె | ఏ | కే | ఐ | కై | ఒ | కొ | ఓ | కో | ఔ | కౌ | ఋ | కృ | ౠ | కౄ | ఌ | కౢ | ౡ | కౣ | అం | కం | అః | కః | క్ | ||||

| Kannada | ಅ | ಕ | ಆ | ಕಾ | ಇ | ಕಿ | ಈ | ಕೀ | ಉ | ಕು | ಊ | ಕೂ | ಎ | ಕೆ | ಏ | ಕೇ | ಐ | ಕೈ | ಒ | ಕೊ | ಓ | ಕೋ | ಔ | ಕೌ | ಋ | ಕೃ | ೠ | ಕೄ | ಌ | ಕೢ | ೡ | ಕೣ | అం | ಕಂ | అః | ಕಃ | ಕ್ | ||||

| Sinhala | අ | ක | ආ | කා | ඇ | කැ | ඈ | කෑ | ඉ | කි | ඊ | කී | උ | කු | ඌ | කූ | එ | කෙ | ඒ | කේ | ඓ | කෛ | ඔ | කො | ඕ | කෝ | ඖ | කෞ | සෘ | කෘ | සෲ | කෲ | ඏ | කෟ | ඐ | කෳ | අං | කං | අඃ | කඃ | ක් |

| Malayalam | അ | ക | ആ | കാ | ഇ | കി | ഈ | കീ | ഉ | കു | ഊ | കൂ | എ | കെ | ഏ | കേ | ഐ | കൈ | ഒ | കൊ | ഓ | കോ | ഔ | കൗ | ഋ | കൃ | ൠ | കൄ | ഌ | കൢ | ൡ | കൣ | അം | കം | അഃ | കഃ | ക്,ക് | ||||

| Tamil | அ | க | ஆ | கா | இ | கி | ஈ | கீ | உ | கு | ஊ | கூ | எ | கெ | ஏ | கே | ஐ | கை | ஒ | கொ | ஓ | கோ | ஔ | கௌ | அஂ | கஂ | அஃ | கஃ | க் | ||||||||||||

| Chakma | 𑄃𑄧 | 𑄇𑄧 | 𑄃 | 𑄇 | 𑄃𑄬𑄬 | 𑄇𑄬𑄬 | 𑄃𑅅 | 𑄇𑅅 | 𑄄, 𑄃𑄨 | 𑄇𑄨 | 𑄃𑄩 | 𑄇𑄩 | 𑄅, 𑄃𑄪 | 𑄇𑄪 | 𑄃𑄫 | 𑄇𑄫 | 𑄆, 𑄃𑄬 | 𑄇𑄬 | 𑄃𑄰 | 𑄇𑄰 | 𑄃𑄮 | 𑄇𑄮 | 𑄃𑄯 | 𑄇𑄯 | 𑄃𑄧𑄁 | 𑄇𑄧𑄁 | 𑄃𑄧𑄂 | 𑄇𑄧𑄂 | 𑄇𑄴 | ||||||||||||

| Burmese | အ | က | အာ | ကာ | အယ် | ကယ် | အွ | ကွ | ဣ | ကိ | ဤ | ကီ | ဥ | ကု | ဦ | ကူ | ဧ | ကေ | အေး | ကေး | အိုင် | ကိုင် | ဩ | ကော | ဪ | ကော် | ၒ | ကၖ | ၓ | ကၗ | ၔ | ကၘ | ၕ | ကၙ | အံ | ကံ | အး | ကး | က် | ||

| Khmer[lower-alpha 3] | អ | ក | អា | កា | ឥ | កិ | ឦ | កី | ឧ | កុ | ឩ | កូ | ឯ | កេ | ឰ | កៃ | ឱ | កោ | ឳ | កៅ | ឫ | ក្ឫ | ឬ | ក្ឬ | ឭ | ក្ឭ | ឮ | ក្ឮ | អំ | កំ | អះ | កះ | ក៑ | ||||||||

| Thai[lower-alpha 4] | อ (อะ) | ก (กะ) | อา | กา | แอ | แก | (ออ) | (กอ) | อิ | กิ | อี | กี | อุ | กุ | อู | กู | (เอะ) | (เกะ) | เอ | เก | ไอ | ไก | (โอะ) | (โกะ) | โ | โก | เอา | เกา | ฤ | กฺฤ | ฤๅ | กฺฤๅ | ฦ | กฺฦ | ฦๅ | กฺฦๅ | อํ | กํ | อะ (อะฮฺ) | กะ (กะฮฺ) | กฺ (ก/ก์) |

| Lao[lower-alpha 4] | ກະ,ກັ | ກາ | ກິ | ກີ | ກຸ | ກູ | ເກ | ໄກ/ໃກ | ໂກ | ເກົາ/ກາວ | ອํ | ກํ | ອະ | ກະ | ກ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cham | ꨀ | ꨆ | ꨀꨩ | ꨆꨩ | ꨁ | ꨆꨪ | ꨁꨩ | ꨆꨫ | ꨂ | ꨆꨭ | ꨂꨩ | ꨆꨭꨩ | ꨃ | ꨆꨯꨮ | ꨄ | ꨆꨰ | ꨅ | ꨆꨯ | ꨀꨯꨱ | ꨆꨯꨱ | ꨣꨮ | ꨆꨴꨮ | ꨣꨮꨩ | ꨆꨴꨮꨩ | ꨤꨮ | ꨆꨵꨮ | ꨤꨮꨩ | ꨆꨵꨮꨩ | ꨀꩌ | ꨆꩌ | ꨀꩍ | ꨆꩍ | ꩀ | ||||||||

| Balinese | ᬅ | ᬓ | ᬆ | ᬓᬵ | ᬇ | ᬓᬶ | ᬈ | ᬓᬷ | ᬉ | ᬓᬸ | ᬊ | ᬓᬹ | ᬏ | ᬓᬾ | ᬐ | ᬓᬿ | ᬑ | ᬓᭀ | ᬒ | ᬓᭁ | ᬋ | ᬓᬺ | ᬌ | ᬓᬻ | ᬍ | ᬓᬼ | ᬎ | ᬓᬽ | ᬅᬂ | ᬓᬂ | ᬅᬄ | ᬓᬄ | ᬓ᭄ | ||||||||

| Javanese | ꦄ | ꦏ | ꦄꦴ | ꦏꦴ | ꦆ | ꦏꦶ | ꦇ | ꦏꦷ | ꦈ | ꦏꦸ | ꦈꦴ | ꦏꦹ | ꦌ | ꦏꦺ | ꦍ | ꦏꦻ | ꦎ | ꦏꦺꦴ | ꦎꦴ | ꦏꦻꦴ | ꦉ | ꦏꦽ | ꦉꦴ | ꦏꦽꦴ | ꦊ | ꦏ꧀ꦭꦼ | ꦋ | ꦏ꧀ꦭꦼꦴ | ꦄꦁ | ꦏꦁ | ꦄꦃ | ꦏꦃ | ꦏ꧀ | ||||||||

| Sundanese | ᮃ | ᮊ | ᮆ | ᮊᮦ | ᮉ | ᮊᮩ | ᮄ | ᮊᮤ | ᮅ | ᮊᮥ | ᮈ | ᮊᮦ | ᮇ | ᮊᮧ | ᮻ | ᮊ᮪ᮻ | ᮼ | ᮊ᮪ᮼ | ᮃᮀ | ᮊᮀ | ᮃᮂ | ᮊᮂ | ᮊ᮪ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lontara | ᨕ | ᨀ | ᨕᨛ | ᨕ | ᨕᨗ | ᨀᨛ | ᨕᨘ | ᨀᨘ | ᨕᨙ | ᨀᨙ | ᨕᨚ | ᨀᨚ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rejang | ꥆ | ꤰ | ꥆꥎ | ꤰꥎ | ꥆꥍ | ꤰꥍ | ꥆꥇ | ꤰꥇ | ꥆꥈ | ꤰꥈ | ꥆꥉ | ꤰꥉ | ꥆꥊ | ꤰꥊ | ꥆꥋ | ꤰꥋ | ꥆꥌ | ꤰꥌ | ꥆꥏ | ꤰꥏ | ꥆꥒ | ꤰꥒ | ꤰ꥓ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Batak (Toba) | ᯀ | ᯂ | ᯤ | ᯂᯪ | ᯥ | ᯂᯮ | ᯂᯩ | ᯂᯬ | ᯀᯰ | ᯂᯰ | ᯀᯱ | ᯂᯱ | ᯂ᯲ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baybayin | ᜀ | ᜃ | ᜁ | ᜃᜒ | ᜂ | ᜃᜓ | ᜁ | ᜃᜒ | ᜂ | ᜃᜓ | ᜃ᜔ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Buhid | ᝀ | ᝃ | ᝁ | ᝃᝒ | ᝂ | ᝃᝓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanunuo | ᜠ | ᜣ | ᜡ | ᜣᜲ | ᜢ | ᜣᜳ | ᜣ᜴ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagbanwa | ᝠ | ᝣ | ᝡ | ᝣᝲ | ᝢ | ᝣᝳ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO | a | ka | ā | kā | ê | kê | ô | kô | i | ki | ī | kī | u | ku | ū | kū | e | ke | ē | kē | ai | kai | o | ko | ō | kō | au | kau | r̥ | kr̥ | r̥̄ | kr̥̄ | l̥ | kl̥ | l̥̄ | kl̥̄ | ṁ | kṁ | ḥ | kḥ | k |

| a | ā | ê | ô | i | ī | u | ū | e | ē | ai | o | ō | au | r̥ | r̥̄ | l̥ | l̥̄ | ṁ | ḥ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

- Notes

- Letters for r̥̄, l̥, l̥̄ and a few others are obsolete or very rarely used.

- includes supplementary vowels not in contemporary use

- When used to write their own languages, Khmer can have either an a or an o as the inherent vowel, following the rules of its orthography.

- Thai and Lao scripts do not have independent vowel forms, for syllables starting with a vowel sound, a "zero" consonant, อ and ອ, respectively, to represent the glottal stop /ʔ/.

Numerals

| Hindu-Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brahmi numbers | 𑁒 | 𑁓 | 𑁔 | 𑁕 | 𑁖 | 𑁗 | 𑁘 | 𑁙 | 𑁚 | |

| Brahmi digits | 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 |

| Assamese | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Bengali | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Tirhuta | 𑓐 | 𑓑 | 𑓒 | 𑓓 | 𑓔 | 𑓕 | 𑓖 | 𑓗 | 𑓘 | 𑓙 |

| Odia | ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

| Devanagari | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Gujarati | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ |

| Gurmukhi | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Meitei (Manipuri) | ꯰ | ꯱ | ꯲ | ꯳ | ꯴ | ꯵ | ꯶ | ꯷ | ꯸ | ꯹ |

| Tibetan | ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ |

| Mongolian[lower-alpha 1] | ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ |

| Lepcha | ᱀ | ᱁ | ᱂ | ᱃ | ᱄ | ᱅ | ᱆ | ᱇ | ᱈ | ᱉ |

| Limbu | ᥆ | ᥇ | ᥈ | ᥉ | ᥊ | ᥋ | ᥌ | ᥍ | ᥎ | ᥏ |

| Sinhala astrological numbers | ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ |

| Sinhala archaic numbers | 𑇡 | 𑇢 | 𑇣 | 𑇤 | 𑇥 | 𑇦 | 𑇧 | 𑇨 | 𑇩 | |

| Telugu | ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| Kannada | ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ |

| Malayalam | ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ |

| Tamil | ೦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ |

| Saurashtra | ꣐ | ꣑ | ꣒ | ꣓ | ꣔ | ꣕ | ꣖ | ꣗ | ꣘ | ꣙ |

| Ahom | 𑜰 | 𑜱 | 𑜲 | 𑜳 | 𑜴 | 𑜵 | 𑜶 | 𑜷 | 𑜸 | 𑜹 |

| Chakma | 𑄶 | 𑄷 | 𑄸 | 𑄹 | 𑄺 | 𑄻 | 𑄼 | 𑄽 | 𑄾 | 𑄿 |

| Burmese | ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ |

| Shan | ႐ | ႑ | ႒ | ႓ | ႔ | ႕ | ႖ | ႗ | ႘ | ႙ |

| Khmer | ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ |

| Thai | ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ |

| Lao | ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ |

| Cham | ꩐ | ꩑ | ꩒ | ꩓ | ꩔ | ꩕ | ꩖ | ꩗ | ꩘ | ꩙ |

| Tai Tham[lower-alpha 2] | ᪐ | ᪑ | ᪒ | ᪓ | ᪔ | ᪕ | ᪖ | ᪗ | ᪘ | ᪙ |

| Tai Tham (Hora)[lower-alpha 3] | ᪀ | ᪁ | ᪂ | ᪃ | ᪄ | ᪅ | ᪆ | ᪇ | ᪈ | ᪉ |

| New Tai Lue | ᧐ | ᧑ | ᧒ | ᧓ | ᧔ | ᧕ | ᧖ | ᧗ | ᧘ | ᧙ |

| Balinese | ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ |

| Javanese | ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ |

| Sundanese | ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ |

| Hindu-Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

- Notes

- Mongolian numerals are derived from Tibetan numerals and used in conjunction with the Mongolian and Clear script

- for liturgical use

- for everyday use

List of Brahmic scripts

Historical

Early Brahmic scripts IAST Ashoka Girnar Chandra

-guptaGujarat Allahabad Narbada Kistna a

ā

i

ī

u

ū

ṛ

e

ai

o

au

k

kh

g

gh

ṅ

c

ch

j

jh

ñ

ṭ

ṭh

ḍ

ḍh

ṇ

t

th

d

dh

n

p

ph

b

bh

m

y

r

l

v

ś

ṣ

s

h

The Brahmi script was already divided into regional variants at the time of the earliest surviving epigraphy around the 3rd century BC. Cursives of the Brahmi script began to diversify further from around the 5th century AD and continued to give rise to new scripts throughout the Middle Ages. The main division in antiquity was between northern and southern Brahmi. In the northern group, the Gupta script was very influential, and in the southern group the Vatteluttu and Old-Kannada/Pallava scripts with the spread of Buddhism sent Brahmic scripts throughout Southeast Asia.

Northern Brahmic

Southern Brahmic

- Tamil-Brahmi, 2nd century BC

- Sinhala

- Bhattiprolu

Unicode

As of Unicode version 13.0, the following Brahmic scripts have been encoded:

| script | derivation | period of derivation | usage notes | ISO 15924 | Unicode range(s) | sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahom | Burmese[6] | 13th century | Extinct Ahom language | Ahom | U+11700–U+1173F | 𑜒𑜠𑜑𑜨𑜉 |

| Balinese | Kawi | 11th century | Balinese language | Bali | U+1B00–U+1B7F | ᬅᬓ᭄ᬲᬭᬩᬮᬶ |

| Batak | Pallava | 14th century | Batak languages | Batk | U+1BC0–U+1BFF | ᯘᯮᯒᯖ᯲ ᯅᯖᯂ᯲ |

| Baybayin | Kawi | 14th century | Tagalog, other Philippine languages | Tglg | U+1700–U+171F | |

| Bengali-Assamese | Siddhaṃ | 11th century | Assamese language (Assamese script variant), Bengali language (Bengali script variant), Bishnupriya Manipuri, Maithili, Angika | Beng | U+0980–U+09FF |

|

| Bhaiksuki | Gupta | 11th century | Was used around the turn of the first millennium for writing Sanskrit | Bhks | U+11C00–U+11C6F | |

| Buhid | Kawi | 14th century | Buhid language | Buhd | U+1740–U+175F | ᝊᝓᝑᝒᝇ |

| Burmese | Pyu | 11th century | Burmese language, numerous modifications for other languages including Chakma, Eastern and Western Pwo Karen, Geba Karen, Kayah, Mon, Rumai Palaung, S’gaw Karen, Shan | Mymr | U+1000–U+109F, U+A9E0–U+A9FF, U+AA60–U+AA7F | မြန်မာအက္ခရာ |

| Chakma | Burmese | 8th century | Chakma language | Cakm | U+11100–U+1114F | 𑄌𑄋𑄴𑄟𑄳𑄦 |

| Cham | Pallava | 8th century | Cham language | Cham | U+AA00–U+AA5F | ꨌꩌ |

| Devanagari | Nagari | 13th century | Numerous Indo-Aryan languages, including Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, Bhili, Konkani, Bhojpuri, Nepal Bhasa and sometimes Sindhi and Kashmiri. Formerly used to write Gujarati. Sometimes used to write or transliterate Sherpa | Deva | U+0900–U+097F, U+A8E0–U+A8FF | देवनागरी |

| Dhives Akuru | Grantha | Was used to write the Maldivian language up until the 20th century.[7] | Diak | U+11900–U+1195F | 𑤞𑥂𑤧𑤭𑥂 | |

| Dogra | Takri | Was used to write Dogri. Dogra script is closely related to Takri.[8] | Dogr | U+11800–U+1184F | 𑠖𑠵𑠌𑠤𑠬 | |

| Grantha | Pallava | 6th century | Restricted use in traditional Vedic schools to write Sanskrit. Was widely used by Tamil speakers for Sanskrit and the classical language Manipravalam. | Gran | U+11300–U+1137F | |

| Gujarati | Nagari | 17th century | Gujarati language, Kutchi language | Gujr | U+0A80–U+0AFF | ગુજરાતી લિપિ |

| Gunjala Gondi | 16th century | Used for writing the Adilabad dialect of the Gondi language.[9] | Gong | U+11D60–U+11DAF | ||

| Gurmukhi | Sharada | 16th century | Punjabi language | Guru | U+0A00–U+0A7F | ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ |

| Hanunó'o | Kawi | 14th century | Hanuno'o language | Hano | U+1720–U+173F | ᜱᜨᜳᜨᜳᜢ |

| Javanese | Kawi | 16th century | Javanese language, Sundanese language, Madurese language | Java | U+A980–U+A9DF | ꦄꦏ꧀ꦱꦫꦗꦮ |

| Kaithi | Nagari | 16th century | Historically used for writing legal, administrative, and private records. | Kthi | U+11080–U+110CF | 𑂍𑂶𑂟𑂲 |

| Kannada | Telugu-Kannada | 9th century | Kannada language, Konkani language Tulu, Badaga, Kodava, Beary others | Knda | U+0C80–U+0CFF | ಕನ್ನಡ ಅಕ್ಷರಮಾಲೆ |

| Khmer | Pallava | 11th century | Khmer language | Khmr | U+1780–U+17FF, U+19E0–U+19FF | អក្សរខ្មែរ |

| Khojki | Landa | 16th century | Some use by Ismaili communities. Was used by the Khoja community for Muslim religious literature. | Khoj | U+11200–U+1124F | |

| Khudawadi | Landa | 16th century | Was used by Sindhi communities for correspondence and business records. | Sind | U+112B0–U+112FF | 𑊻𑋩𑋣𑋏𑋠𑋔𑋠𑋏𑋢 |

| Lao | Khmer | 14th century | Lao language, others | Laoo | U+0E80–U+0EFF | ອັກສອນລາວ |

| Lepcha | Tibetan | 8th century | Lepcha language | Lepc | U+1C00–U+1C4F | ᰛᰩᰴ |

| Limbu | Lepcha | 9th century | Limbu language | Limb | U+1900–U+194F | ᤛᤡᤖᤡᤈᤨᤅ |

| Lontara | Kawi | 17th century | Buginese language, others | Bugi | U+1A00–U+1A1F | ᨒᨚᨈᨑ |

| Mahajani | Landa | 16th century | Historically used in northern India for writing accounts and financial records. | Mahj | U+11150–U+1117F | |

| Makasar | Kawi | Was used in South Sulawesi, Indonesia for writing the Makassarese language.[10] Makasar script is also known as "Old Makassarese" or "Makassarese bird script" in English-language scholarly works.[11] | Maka | U+11EE0–U+11EFF | ||

| Malayalam | Grantha | 12th century | Malayalam language | Mlym | U+0D00–U+0D7F | മലയാളലിപി |

| Marchen | Tibetan | 7th century | Was used in the Tibetan Bön tradition to write the extinct Zhang-Zhung language | Marc | U+11C70–U+11CBF | 𑱳𑲁𑱽𑱾𑲌𑱵𑲋𑲱𑱴𑱶𑲱𑲅𑲊𑱱 |

| Meetei Mayek | Siddhaṃ | 17th century | Historically used for the Meitei language. Some modern usage. | Mtei | U+AAE0–U+AAFF, U+ABC0–U+ABFF | ꯃꯤꯇꯩ ꯃꯌꯦꯛ |

| Modi | Devanagari | 17th century | Was used to write the Marathi language | Modi | U+11600–U+1165F | 𑘦𑘻𑘚𑘲 |

| Multani | Landa | Was used to write the Multani language | Mult | U+11280–U+112AF | ||

| Nandinagari | Nāgarī | 7th century | Historically used to write Sanskrit in southern India | Nand | U+119A0–U+119FF | |

| New Tai Lue | Tai Tham | 1950s | Tai Lü language | Talu | U+1980–U+19DF | ᦟᦲᧅᦎᦷᦺᦑ |

| Odia | Siddhaṃ | 13th century | Odia language | Orya | U+0B00–U+0B7F | ଓଡ଼ିଆ ଅକ୍ଷର |

| 'Phags-Pa | Tibetan | 13th century | Historically used during the Mongol Yuan dynasty. | Phag | U+A840–U+A87F | ꡖꡍꡂꡛ ꡌ |

| Prachalit (Newa) | Nepal | Has been used for writing the Sanskrit, Nepali, Hindi, Bengali, and Maithili languages | Newa | U+11400–U+1147F | 𑐥𑑂𑐬𑐔𑐮𑐶𑐟 | |

| Rejang | Kawi | 18th century | Rejang language, mostly obsolete | Rjng | U+A930–U+A95F | ꥆꤰ꥓ꤼꤽ ꤽꥍꤺꥏ |

| Saurashtra | Grantha | 20th century | Saurashtra language, mostly obsolete | Saur | U+A880–U+A8DF | ꢱꣃꢬꢵꢰ꣄ꢜ꣄ꢬꢵ |

| Sharada | Gupta | 8th century | Was used for writing Sanskrit and Kashmiri | Shrd | U+11180–U+111DF | 𑆯𑆳𑆫𑆢𑆳 |

| Siddham | Gupta | 7th century | Was used for writing Sanskrit | Sidd | U+11580–U+115FF | 𑖭𑖰𑖟𑖿𑖠𑖽 |

| Sinhala | Brahmi[12] | 4th century[13] | Sinhala language | Sinh | U+0D80–U+0DFF, U+111E0–U+111FF | ශුද්ධ සිංහල |

| Sundanese | Kawi | 14th century | Sundanese language | Sund | U+1B80–U+1BBF, U+1CC0–U+1CCF | ᮃᮊ᮪ᮞᮛ ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ |

| Sylheti Nagari | Nagari | 16th century | Historically used for writing the Sylheti language | Sylo | U+A800–U+A82F | ꠍꠤꠟꠐꠤ ꠘꠣꠉꠞꠤ |

| Tagbanwa | Kawi | 14th century | various languages of Palawan, nearly extinct | Tagb | U+1760–U+177F | ᝦᝪᝨᝯ |

| Tai Le | Mon | 13th century | Tai Nüa language | Tale | U+1950–U+197F | ᥖᥭᥰᥖᥬᥳᥑᥨᥒᥰ |

| Tai Tham | Mon | 13th century | Northern Thai language, Tai Lü language, Khün language | Lana | U+1A20–U+1AAF | ᨲᩫ᩠ᩅᨾᩮᩬᩥᨦ |

| Tai Viet | Thai | 16th century | Tai Dam language | Tavt | U+AA80–U+AADF | ꪼꪕꪒꪾ |

| Takri | Sharada | 16th century | Was used for writing Chambeali, and other languages | Takr | U+11680–U+116CF | 𑚔𑚭𑚊𑚤𑚯 |

| Tamil | Pallava | 5th century CE[14] | Tamil language | Taml | U+0B80–U+0BFF, U+11FC0–U+11FFF | தமிழ் அரிச்சுவடி |

| Telugu | Telugu-Kannada | 5th century | Telugu language | Telu | U+0C00–U+0C7F | తెలుగు లిపి |

| Thai | Khmer | 13th century | Thai language | Thai | U+0E00–U+0E7F | อักษรไทย |

| Tibetan | Gupta | 8th century | Tibetan language, Dzongkha language, Ladakhi language | Tibt | U+0F00–U+0FFF | བོད་ཡིག་ |

| Tirhuta | Siddham | 13th century | Historically used for the Maithili language | Tirh | U+11480–U+114DF | 𑒞𑒱𑒩𑒯𑒳𑒞𑒰 |

See also

- Devanagari transliteration

- International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration

- National Library at Kolkata romanization

- Bharati Braille, the unified braille assignments of Indian languages

- Indus script – the earliest writing system on the Indian subcontinent

- ISCII – the coding scheme specifically designed to represent Indic scripts

References

- https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/63062039

- Trautmann, Thomas R. (2006). Languages and Nations: The Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras. University of California Press. pp. 65–66.

- Coningham, R. A. E.; Allchin, F. R.; Batt, C. M.; Lucy, D. (April 1996). "Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the Early Use of the Brahmi Script". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 6 (1): 73–97. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001608.

- "Font: Japanese". Monotype Corporation. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Adluri, Seshu Madhava Rao; Paruchuri, Sreenivas (February 1999). "Evolution of Telugu Character Graphs". Notes on Telugu Script. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Terwiel; Khamdaengyodtai (2003). Shan Manuscripts,Part 1. p. 13.

- Pandey, Anshuman (23 January 2018). "L2/18-016R: Proposal to encode Dives Akuru in Unicode" (PDF).

- Pandey, Anshuman (4 November 2015). "L2/15-234R: Proposal to encode the Dogra script" (PDF).

- "Chapter 13: South and Central Asia-II" (PDF). The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0. Mountain View, CA: Unicode, Inc. June 2018. ISBN 978-1-936213-19-1.

- "Chapter 17: Indonesia and Oceania" (PDF). The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0. Mountain View, CA: Unicode, Inc. June 2018. ISBN 978-1-936213-19-1.

- Pandey, Anshuman (2 November 2015). "L2/15-233: Proposal to encode the Makasar script in Unicode" (PDF).

- Daniels (1996), p. 379.

- Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. p. 389.

- Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. p. 385.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brahmic scripts. |

- Online Tool which supports Conversion between various Brahmic Scripts

- Windows Indic Script Support

- An Introduction to Indic Scripts

- South Asian Writing Systems

- Enhanced Indic Transliterator Transliterate from romanised script to Indian Languages.

- Indian Transliterator A means to transliterate from romanised to Unicode Indian scripts.

- Imperial Brahmi Font and Text-Editor

- Brahmi Script

- Xlit: Tool for Transliteration between English and Indian Languages

- Padma: Transformer for Indic Scripts – a Firefox add-on