Architecture of Africa

Like other aspects of the culture of Africa, the architecture of Africa is exceptionally diverse. Throughout the history of Africa, Africans have developed their own local architectural traditions. In some cases, broader regional styles can be identified, such as the Sudano-Sahelian architecture of West Africa. A common theme in traditional African architecture is the use of fractal scaling: small parts of the structure tend to look similar to larger parts, such as a circular village made of circular houses.[1]

African architecture in some areas has been influenced by external cultures for centuries, according to available evidence. Western architecture has influenced coastal areas since the late 15th century and is now an important source of inspiration for many larger buildings, particularly in major cities.

African architecture uses a wide range of materials, including thatch, stick/wood, mud, mudbrick, rammed earth, and stone. These material preferences vary by region: North Africa for stone and rammed earth, the Horn of Africa for stone and mortar, West Africa for mud/adobe, Central Africa for thatch/wood and more perishable materials, Southeast and Southern Africa for stone and thatch/wood.

Early architecture

Probably the most famous class of structure in all Africa, the Pyramids of Egypt remain one of the world's greatest early architectural achievements, regardless of practicality and origins in a funerary context. Egyptian architectural traditions also favored the building of vast temple complexes.

Little is known of ancient architecture south and west of the Sahara. Harder to date than the pyramids are the monoliths around the Cross River, which have geometric or human designs. The vast number of Senegambian stone circles is also evidence of an emerging architecture.

Egypt

Egypt's achievements in architecture included temples, enclosed cities, canals, and dams.

Amazigh architecture

Thousands of pre-Christian tombs were left by the Berbers, whose architecture was unique to northwest Africa. The most famous was the Tomb of the Christian Woman in western Algeria. This structure consists of columns, a dome, and spiral pathways that lead to a single chamber.[3]

Massive Amazigh pisé mudbrick buildings date from 110 BCE. A common feature of Amazigh architecture is the agadir, or fortified granary.[2][4] Cities such as Ceuta, Chellah, and Volubilis were influenced by Phoenician and Roman architecture.[5]

Nubia

Nubian architecture is one of the most ancient in the world. The earliest style of Nubian architecture includes the speos, structures carved out of solid rock under the A-Group culture (3700-3250 BCE). Egyptians borrowed and made extensive use of the process at Speos Artemidos and Abu Simbel.[6] A-Group culture led eventually to the C-Group culture, which began building using light, supple materials—animal skins and wattle and daub—with larger structures of mudbrick later becoming the norm.

The C-Group culture was related to that of the city of Kerma,[7] which was settled around 2400 BC. It was a walled city containing religious buildings, large circular dwellings, a palace, and well-laid-out roads. On the east side of the city, a funerary temple and chapel were laid out. It supported a population of 2,000. One of its most enduring structures was the Deffufa, a mudbrick temple, on top of which ceremonies were performed.

Between 1500 and 1085 BC, Egypt conquered and dominated Nubia, which brought about the Napatan phase of Nubian history: the birth of the Kingdom of Kush. Kush was immensely influenced by Egypt and eventually conquered Egypt. During this phase, we see the building of numerous pyramids and temples. Gebel Barkal, in the town of Napata, was a significant site, where Kushite pharaohs received legitimacy.

Thirteen temples and two palaces have been excavated in Napata, which has yet to be fully excavated. Sudan contains 223 Nubian pyramids, more numerous but smaller than the Egyptian pyramids, at three major sites: El Kurru, Nuri, and Meroe. The elements of Nubian pyramids, built for kings and queens, included steep walls, a chapel facing east, a stairway facing east, and a chamber accessed via the stairway.[8][9] The Meroe site has the most pyramids and is considered the largest archaeological site in the world. Around AD 350, the area was invaded by the Kingdom of Aksum and the Napatan kingdom collapsed.[10]

Aksumite

Aksumite architecture flourished in the Ethiopian region, as attested by the numerous Aksumite influences in and around the medieval churches of Lalibela, where stelae (hawilts) and, later, entire churches were carved out of single blocks of rock. Other monumental structures include massive underground tombs often located beneath stelae. Other well-known structures employing monolithic construction include the Tomb of the False Door, and the tombs of Kaleb and Gebre Mesqel in Axum.

Most structures, however—such as palaces, villas, commoner's houses, and other churches and monasteries—were built of alternating layers of stone and wood. Some examples of this style had whitewashed exteriors and/or interiors, such as the medieval 12th-century monastery of Yemrehanna Krestos, which was built in Aksumite style. Contemporary houses were one-room stone structures, two-storey square houses, or roundhouses of sandstone with basalt foundations. Villas were generally two-to-four storeys tall and had sprawling rectangular plans (cf. Dungur ruins). A good example of still-standing Aksumite architecture is the monastery of Debre Damo from the 6th century.

Tichitt Walata

Tichitt Walata is the oldest surviving collection of settlements in West Africa and the oldest of all stone-base settlement south of the Sahara. It was built by the Soninke people and is thought to be the precursor of the Ghana empire.[11] It was settled by agropastoral people around 2000–300 BCE, which makes it almost 1000 years older than previously thought.[12] One finds well-laid-out streets and fortified compounds, all made out of skilled stone masonry. In all, there were 500 settlements.[13][14]

Nok

Nok culture artifacts—located on the Jos Plateau in Nigeria, between the Niger River and Benue River—have been dated as far back as 790 BCE. The excavation of the Nok settlement in Samun Dikiya shows a tendency to build on hill tops and mountain peaks. However, Nok settlements have not been extensively excavated.[15]

Sao civilization sites of walled-cities are in the Lake Chad region, along the Chari River; the oldest site—at Zilum, Chad—dates to at least the first millennium.

Gobarau Mosque

Gobarau Mosque is believed to have been completed during the reign of Muhammadu Korau (1398–1408), the first Muslim king of Katsina. Originally built as the central mosque of Katsina town, it was later also used as a school. By the beginning of the 16th century, Katsina had become a very important commercial and academic center in Hausaland, and Gobarau Mosque had grown into a famed Islamic institution of higher learning. Gobarau continued to be Katsina's central mosque until the beginning of the 19th century AD.

Other pre-colonial Nigerian societies

Several societies in pre-colonial Nigeria built structures from earth and stone. In general, these structures were primarily defensive, repelling invaders from other tribes, but many settlements put spiritual elements into their construction. These defensive structures were primarily constructed from earth, occasionally plastered.

Dump ramparts consist of an outer ditch and inner bank and can span from 1/2 meter to 20 meters across in the largest settlements such as Benin and Sungbo's Eredo. Coursed mud walls in the Guinea and Sudan savannas were laid in layers of mud. Each layer of mud would be held in place by wooden framing, allowed to dry, and built on top of. At the most significant settlement in Koso, these walls averaged 6 meters in height, tapering from 2 meters thick at the base to 1/2 meter thick at the top. Tubali walls in northern Nigeria have two components: sun-dried mud bricks held together with mud mortar. Walls in this style have a tendency to deteriorate in wetter climates.[16]

These mud constructions were usually plastered with mud mixed with other materials. The defensive purpose of this was to create a smoother, unscalable surface to help repel attackers. However, some plaster has been found with blood, bone remains, gold dust, oil, and straw mixed in. Some of these materials were functional, adding strength, while others had spiritual meanings, possibly to defend against evil spirits.[16]

Benin City in particular had sophisticated house and urban planning. Houses had several rooms and were usually roofed, enclosing private quarters, sacred spaces, and rooms for receiving guests. Usually, multiple houses would enclose a shared courtyard. When it rained, the house roofs would collect water into a space in the courtyard for later use. Houses would have public frontage along long, straight roads. The city had markets and the chief's palace in the center of the city, with dominant and subordinate roads leading outwards. HM Stanely, quoted in Asomani-Boateng, Raymond (2011-11), described the roads as "...fenced with tall [water cane] neatly set very close together in uniform rows..." possibly for privacy.[17]

More sophisticated construction methods include stone and brick constructions, with and without mortar, plaster, and accompanying defensive structures. Fired brick constructions were observed in settlements in northeast Nigeria, such as historic Kanuri buildings. Many of the bricks have since been removed for new constructions. Laterite block walls with clay mortar were found in northwest Nigeria, possibly inspired by Songhai constructions. Walls built from stone without mortar have been found where societies could obtain sufficient stone, most notably in Sukur. None of these constructions have been observed with additional plastering.[16]

The Sukur World Heritage Site is especially significant, with extensive terraces, walls, and infrastructure. Walls separate homes, animal pens, and granaries, while terraces often include spiritual items such as sacred trees or ceramic shrines. Early iron foundries were also present, usually placed close to the homes of their owners.[18]

Broadly, three styles of residential architecture can be identified in indigenous Nigerian architecture, relating to the people groups which developed them.

- Hausa architecture uses plastered adobe to create monolithic walls. Roofing is provided by shallow domes and vaults made from structural timber beams covered by laterite and earth. Homesteads are bounded by perimeter walls with both circular and linear interior divisions with one clearly defined entrance.

- Yoruba architecture uses cured earth walls to support roof timbers, over which leaf or woven grass roofing is applied. These walls are usually homogeneous mud structures, though wattle-and-daub techniques can be found in certain locations. Space is divided into individual units which are then connected by proximity and walls into a compound with courtyards and private spaces. Multiple entrances and exits allow access to accessory facilities such as kitchens.

- Igbo architecture uses similar construction techniques and materials as Yoruba architecture, but varies significantly in spatial arrangement. No unified compound walls exist in these constructions. Instead, individual units are related to a central leader's hut, with significance attached to relative position and size.

These elements are believed to affect present-day residential house design, especially when designating spaces as public, semi-public, semi-private, or private.[19]

Medieval architecture

North Africa

The Islamic conquest of North Africa saw the development of Islamic architecture in the region, including such famous structures as the Great Mosque of Kairouan or the Cairo Citadel. The sahn is a prominent early feature of Islamic architecture.

Around 1000 AD, cob (tabya) first appears in the Maghreb and al-Andalus.[20]

Morocco

Islamic architecture developed in Morocco under the Idrisid dynasty, with structures such as the University of al-Qarawiyyin.[21] The Almoravid dynasty united northwest Africa and Iberia under one empire, and brought Andalusi architects to North Africa.[22][23] Some features of Moroccan Islamic architecture are the riad, square-based minarets, tadelakt plaster, and decorative features such as arabesque and zellige.[24]

Under the Saadi dynasty, Marble from Carrara, bought with Moroccan sugar, was used in the furnishing of palaces and mosques.[25]

Remains of an Idrisid mosque at Lixus.

Remains of an Idrisid mosque at Lixus..jpg.webp)

El Badi Palace in Marrakesh.

El Badi Palace in Marrakesh.

Somalia

Somali architecture has a rich and diverse tradition of designing and engineering different types of construction, such as masonry, castles, citadels, fortresses, mosques, temples, aqueducts, lighthouses, towers and tombs, during the ancient, medieval, and early modern periods in Somalia. It also encompasses the fusion of Somalo-Islamic architecture with Western designs in modern times.

In ancient Somalia, pyramidical structures known in Somali as taalo were a popular burial style, with hundreds of these dry stone monuments scattered around the country today. Houses were built of dressed stone similar to the ones in Ancient Egypt,[26] and there are examples of courtyards, and large stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall, enclosing settlements.

The peaceful introduction of Islam in the early medieval era of Somalia's history brought Islamic architectural influences from Arabia and Persia, which stimulated a shift in construction from dry stone, and other related materials, to coral stone, sun-dried bricks, and the widespread use of limestone in Somali architecture. Many of the new architectural designs, such as mosques, were built on the ruins of older structures, a practice that would continue over and over again throughout the following centuries.[27]

Aksumite

Throughout the medieval period, the monolithic influences of Aksumite architecture persisted, with its influence felt strongest in the early medieval (Late Aksumite) and Zagwe periods (when the churches of Lalibela were carved). Throughout the medieval period, and especially during the 10th to 12th centuries, churches were hewn out of rock throughout Ethiopia, especially in the northernmost region of Tigray, which was the heart of the Aksumite Empire. However, rock-hewn churches have been found as far south as Adadi Maryam (15th century), about 100 kilometres (62 mi) south of Addis Abeba.

The most famous examples of Ethiopian rock-hewn architecture are the 11 monolithic churches of Lalibela, carved out of the red volcanic tuff found around the town. Although later medieval hagiographies attribute all 11 structures to the eponymous king Lalibela (the town was called Roha and Adefa before his reign), new evidence indicates that they may have been built separately over a period of a few centuries, with only a few of the more recent churches having been built under his reign. Archaeologist and Ethiopisant David Phillipson postulates that Bete Gebriel-Rufa'el was actually built in the very early medieval period, some time between 600 and 800 AD, originally as a fortress but later turned into a church.

West Africa

Ghana

At Kumbi Saleh, locals lived in dome-shaped dwellings in the king's section of the city, surrounded by a great enclosure. Traders lived in stone houses in a section which possessed 12 beautiful mosques (as described by al-Bakri), one of which was for Friday prayer.[28] The king is said to have owned several mansions, one of which was sixty-six feet long and forty-two feet wide, contained seven rooms, was two stories high, and had a staircase, with paintings on the walls and chambers filled with sculpture.[29]

Sahelian architecture initially grew from the two cities of Djenné and Timbuktu. The Sankore Mosque, constructed from mud on timber, was similar in style to the Great Mosque of Djenné.

Ashanti

Ashanti architecture from Ghana is perhaps best known from the reconstruction at Kumasi. Its key features are courtyard-based buildings, and walls with striking reliefs in brightly painted mud plaster. An example of a shrine can be seen at Bawjiase in Ghana. Four rectangular rooms, constructed from wattle and daub, lie around a courtyard. Animal designs mark the walls, and palm leaves cut to a tiered shape provide the roof.

Yoruba

The Yoruba surrounded their settlements with massive mud walls. Their buildings had a similar plan to the Ashanti shrines, but with verandahs around the court. The walls were of puddled mud and palm oil. The most famous of the Yoruba fortifications, and the second largest wall edifice in Africa, is Sungbo's Eredo, a structure that was built in honour of a traditional oloye by the name of Bilikisu Sungbo, in the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries. The structure is made up of sprawling mud walls among the valleys that surrounded the town of Ijebu-Ode in Ogun State. Sungbo's Eredo is the largest pre-colonial monument in Africa, larger than the Great Pyramids or Great Zimbabwe.

Kanem-Bornu

Kanem-Bornu's capital city, Birni N'Gazargamu, may have had a population of 200,000. It had four mosques, which could hold up to 12,000 worshippers. It was surrounded by a 25-foot-high (7.6 m) wall more than 1-mile (1.6 km) in circumference. Many large streets extended from the esplanade and connected to 660 roads. The main buildings were built with red brick. Other buildings were built with straw and adobe.[30]

Hausa Kingdoms

The important Hausa Kingdoms city state of Kano was surrounded by a wall of reinforced ramparts of stone and bricks. Kano contained a citadel near which the royal court resided. Individual residences were separated by earthen walls. The higher the status of the resident the more elaborate the wall. The entrance-way was maze-like to keep women secluded. Inside, near the entrance, were the abodes of unmarried women. Further on were slave quarters.[31]

Benin

The rise of kingdoms in the West African coastal region produced architecture which drew on indigenous traditions, utilizing wood. Benin City, destroyed during the Benin Expedition of 1897, was a large complex of homes in coursed mud, with hipped roofs of shingles or palm leaves. The palace contained a sequence of ceremonial rooms and was decorated with brass plaques. The Walls of Benin City were the world's largest man-made structure.[32] Fred Pearce wrote in New Scientist:

They extend for some 16,000 kilometres in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They cover 6500 square kilometres and were all dug by the Edo people. In all, they are four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops. They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet.[33]

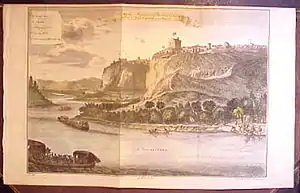

Kongo

With a population of more than 30,000, Mbanza Congo was the capital of the Kingdom of Kongo. The city sat atop a cliff, with a river running below through a forested valley. The king's dwelling was described as an enclosure, a mile-and-a-half in extent, with walled pathways, courtyard, gardens, decorated huts, and palisades. An early explorer described it as looking like a Cretan labyrinth.[34]

Kuba

The capital of the Kuba Kingdom was surrounded by a 40-inch-high (1.0 m) fence. Inside the fence were roads, a walled royal palace, and urban buildings. The palace was rectangular and in the center of the city.[35]

Luba

The Luba tended to cluster in small villages, with rectangular houses facing a single street. Kilolo, patrilineal chieftains, headed the local village government, under the protection of the king. Cultural life centered around the kitenta, the royal compound, which later came to be a permanent capital. The kitenta drew artists, poets, musicians and craftsmen, spurred by royal and court patronage.

Lunda

Musumba the capital of the Kingdom of Lunda, was 100 kilometres (62 mi) from the Kasai River, in open woodland, between two rivers 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) apart. The city was surrounded by fortified earthen ramparts and dry moats. The compound of the Mwato Yamvo (sovereign ruler) was surrounded by large fortifications of double-layered tree, or wood, ramparts. Musumba had multiple courtyards with designated functions, straight roads, and public squares. Its cleanliness was noted by European observers.[36]

Eastern Lunda

The Eastern Lunda dwelling of the Kazembe was described as containing fenced roads a mile long. The enclosing walls were made of grass, 12 to 13 span in height. The enclosed roads led to a rectangular hut opened on the west side. In the center was a wooden base with a statue on top of about 3 span in height.[37]

Maravi

The Maravi people built bridges (uraro) of bamboo because of changing river depths. Bamboo was placed parallel to each other and tied together by bark (maruze). One end of the bridge would be tied to a tree. The bridge would curve downward.

Tanzania

Engaruka is a ruined settlement on the slopes of Mount Ngorongoro in northern Tanzania. Seven stone-terraced villages comprised the settlement. A complex structure of stone channels along the mountain's base was used to dike, dam, and level surrounding river waters for irrigation of individual plots of land. Some of these irrigation channels were several kilometers long. The channels irrigated a total area of 5,000 acres (20 km2).[38][39]

Burundi

Burundi never had a fixed capital. The closest thing to it was a royal hill. When the king moved, his new location became the insago. The compound itself was enclosed inside a high fence and had two entrances. One was for herders and herds. The other was to the royal palace, which was itself surrounded by a fence. The royal palace had three royal courtyards, each serving a particular function: one for herders, one as a sanctuary, and one encompassed by kitchen and granary.[40]

Rwanda

Nyanza was the royal capital of Rwanda. The king's residence, the Ibwami, was built on a hill. Surrounding hills were occupied by permanent or temporary dwellings. These dwellings were round huts surrounded by big yards and tall hedges to separate the compounds. The Rugo, the royal compound, was encircled by reed fences encompassing thatched houses. The houses for the king's entourage were carpeted with mats and had clay hearths in the center. For the king and his wife, the royal house was close to 200-100 yards in length and looked like a huge maze of connected huts and granaries. It had one entrance that lead to a large public square called the karubanda.[41]

Kitara and Bunyoro

In western Uganda, there are numerous earthworks near the Katonga River. These earthworks have been attributed to the Empire of Kitara. The most famous, Bigo Bya Mugenyi, is about 4 square miles (10 km2). The ditch was dug by cutting through 200,000 cubic metres (7,100,000 cu ft) of solid bedrock and earth. The earthwork rampart was about 12 feet (3.7 m) high. It is not certain whether its function was for defense or pastoral use. Little is known about the Ugandan earthworks.[42]

Buganda

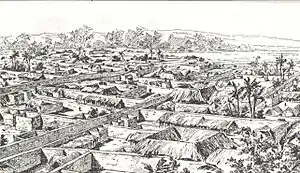

Initially, the hilltop capital, or kibuga, of Buganda would be moved to a new hill with each new ruler, or Kabaka. In the late 19th century, a permanent kibuga of Buganda was established at Mengo Hill. The capital, 1.5 miles across, was divided into quarters corresponding to provinces, with each chief building dwellings for his wife, slaves, dependents and visitors. Large plots of land were available for planting bananas and fruits. Roads were wide and well maintained.[43]

Nubia (Christian and Islamic)

The Christianization of Nubia began in the 6th century. Its most representative architecture consists of churches, whose design is based on Byzantine basilicas, but which are relatively small and made of mud bricks. Vernacular architecture of the Christian period is scarce. Soba is the only city that has been excavated. Its structures are made of sun-dried bricks, the same as today, except for an arch. During the Fatimid phase of Islam, Nubia became Arabized. Its most import mosque was the Mosque of Derr.[44][45]

Swahili States

Farther south, increased trade with Arab merchants, and the development of ports, saw the birth of Swahili architecture. An outgrowth of indigenous Bantu settlements,[46] one of the earliest examples is the Palace of Husuni Kubwa, lying west of Kilwa, built about 1245. As with many other early Swahili buildings, coral rag was the main construction material, and even the roof was constructed by attaching coral to timbers. The palace at Kilwa Kisiwani was a two-story tower, in a walled enclosure. Other notable structures from the period include the pillar tombs of Malindi and Mnarani in Kenya and elsewhere, originally made of coral rag, and later from stone. Later examples include Zanzibar's Stone Town, with its famous carved doors and the Great Mosque of Kilwa.

Afrikaner

Cape Dutch architecture is traditional Afrikaner architecture and is one of the most distinctive types of settler architecture in the world. It was developed during the century-and-a-half that the Cape was a Dutch colony. Even by the end of that period, the early 19th-century, the colony was inhabited by fewer than fifty thousand people, spread over an area roughly the size of the United Kingdom. The Cape Dutch–style buildings showed a remarkable consistency and were clearly related to rural architecture in northwestern Europe but equally clearly having its own unmistakable African character and features.[47]

Shona

Mapungubwe is considered the most socially complex society in southern Africa and the first southern African culture to display economic differentiation. The elite lived separately in a mountain settlement made of sandstone. It was the precursor to Great Zimbabwe. Large amounts of dirt were carried to the top of the hill. At the bottom of the hill was a natural amphitheater, and at the top an elite graveyard. There were only two pathways to the top, one following a narrow steep cleft along the side of the hill of which observers at the top had a clear view.

Great Zimbabwe was the largest medieval city in sub-Saharan Africa. It was constructed and expanded for more than 300 years in a local style that eschewed rectilinearity for flowing curves. Neither the first nor the last of some 300 similar complexes located on the Zimbabwean plateau, Great Zimbabwe is set apart by the large scale of its structures. Its most formidable edifice, commonly referred to as the Great Enclosure, has dressed stone walls as high as 36 feet (11 m) extending for approximately 820 feet (250 m),[48] making it the largest ancient structure south of the Sahara. Houses within the enclosure were circular and constructed of wattle and daub, with conical thatched roofs.

Khami was the capital of the Torwa State. It was the successor to Great Zimbabwe and where the techniques of Great Zimbabwe were further refined and developed. Elaborate walls were constructed by connecting carefully cut stones to form terraced hills.[49]

Sotho-Tswana

Sotho–Tswana architecture represents the other stone-building tradition of southern Africa, centered in the transvaal, highveld north and south of the Vaal. Numerous large stonewalled enclosures and stone-house foundations have been found in the region.[50] Tswana, the capital of the Kwena (ruler), was a stone-walled town as large as the capital of Eastern Lunda.[51]

Zulu and Nguni

Zulu Architecture was constructed with more perishable materials. Dome-shaped huts typically come to mind when one thinks of Zulu dwellings, but later on their design evolved into dome over cylinder-shaped walls. Zulu capital cities were elliptical in plan. The exterior was lined with a durable wood palisade. Domed huts, in rows of 6 to 8, stood just inside the palisade. In the center was the kraal, used by the king to examine his soldiers, hold cattle, or conduct ceremonies. It was an empty circular area at the center of the capital, enclosed by a less durable interior palisade, compared to the exterior. The entrance to the city was opposite to the fortified royal enclosure called the Isigodlo.

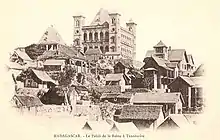

Madagascar

The Southeast Asian origins of the first settlers of Madagascar are reflected in the island's architecture, typified by rectangular dwellings topped with peaked roofs and often built on short stilts. Coastal dwellings, generally made of plant materials, are more like those of East Africa; those of the central highlands tend to be constructed in cob or brick. The introduction of brick-making, by European missionaries in the 19th century, led to the emergence of a distinctly Malagasy architectural style that blends the norms of traditional wooden aristocratic homes with European details.[52]

Namibia

The fortress of ǁKhauxaǃnas, built by the Oorlam in southeastern Namibia, included a wall that was 700 metres (2,300 ft) in length and 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) in height. It was built with stone slabs and displays features of both the Zimbabwean and Transvaal-Free-State styles of stone construction.[53]

Modern architecture

Multiple influences in Ethiopia

In the early modern period, Ethiopia's absorption of diverse new influences—such as Baroque, Arab, Turkish and Gujarati Indian styles—began with the arrival of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries. Portuguese soldiers had initially come in the mid-16th century as allies to aid Ethiopia in its fight against Adal, and the Jesuits came hoping to convert the country.

Some Turkish influence may have entered the country during the late 16th century during Ethiopia's war with the Ottoman Empire (see Habesh), which resulted in an increased building of fortresses and castles. Ethiopia, naturally hard to defensible because of its numerous ambas or flat-topped mountains and rugged terrain, gained little tactical use from these structures, in contrast to advantages they bestowed when placed on the flat terrain of Europe and other areas; and so Ethiopia had not nurtured the tradition. Castle building, especially around the Lake Tana region, began with the reign of Sarsa Dengel; and subsequent emperors maintained the tradition, eventually resulting in the creation of the Fasil Ghebbi (royal enclosure of castles) in the newly founded capital, Gondar (1635).

Emperor Susenyos (r. 1606-1632) converted to Catholicism in 1622 and attempted to make it the state religion, declaring it as such from 1624 until his abdication. During this time, he employed Arab, Gujarati (brought by the Jesuits), Jesuit and local masons, some of whom were Beta Israel, and adopted their styles. With the reign of his son Fasilides, most of these foreigners were expelled, although some of their architectural styles were absorbed into the prevailing Ethiopian architectural style. This style of the Gondarine dynasty would persist throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, especially, and influenced modern 19th-century-and-later styles.

West African colonial fortifications

Early European colonies on the West African coast built large forts, as can be seen at Elmina Castle, Cape Coast Castle, Christiansborg, Fort Jesus, and elsewhere. These were usually plain, with little ornamentation, but with more adornment at Dixcove Fort. Other embellishments were gradually accreted, with the style inspiring later buildings such as Lamu Fort and the stone palace of Kumasi.

European eclecticism

European artists in the 18th century would go out to Africa and the Middle East in hopes of finding new inspiration to include in their art. These travels became common and changed political and cultural relations between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.[54] By the late 19th century, most buildings reflected the fashionable European eclecticism and pastisched Mediterranean, or even Northern European, styles. Examples of colonial towns from this era survive at Saint-Louis, Grand-Bassam, Swakopmund, Cape Town, Luanda. A few buildings were pre-fabricated in Europe and shipped over for erection. This European tradition continued well into the 20th century, with the construction of European-style manor houses, such as Shiwa Ng'andu in what is now Zambia, or the Boer homesteads in South Africa, and with many town buildings.

Traditional revival

The revival of interest in traditional styles can be traced to Cairo in the early 19th century. This had spread to Algiers and Morocco by the early 20th century, from which time colonial buildings across the continent began to consist of pastiches of traditional African architecture, the Jamia Mosque in Nairobi being a typical example. In some cases, architects attempted to mix local and European styles, such as at Bagamoyo.

Modernism

The effect of modern architecture began to be felt in the 1920s and 1930s. Le Corbusier designed several never-built schemes for Algeria, including ones for Nemours and for the reconstruction of Algiers. Elsewhere, Steffen Ahrends was active in South Africa, and Ernst May in Nairobi and Mombasa.

Morocco

Elie Azagury became the first Moroccan modernist architect in the 1950s.[55][56] The Groupe des Architectes Modernes Marocains—at first led by Michel Écochard, director of urban planning under the French Protectorate—was active building public housing in the Hay Mohammedi neighborhood of Casablanca that provided a "culturally specific living tissue" for laborers and migrants from the countryside.[57] Sémiramis, Nid d’Abeille (Honeycomb), and Carrières Centrales were some of the first examples of this Vernacular Modernism.[58] The French-Moroccan architect Jean-François Zevaco also built experimental modernist works in Morocco.[59]

Eritrea

Italian futurist architecture heavily influenced the designs of Asmara. Planned villages were constructed in Libya and Italian East Africa, including the new town of Tripoli, all utilising modern designs.

After 1945, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew extended their work on British schools into Ghana, and also designed the University of Ibadan. The reconstruction of Algiers offered more opportunities, with Sacred Heart Cathedral of Algiers, and universities by Oscar Niemeyer, Kenzo Tange, Jakob Zweifel, and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. But modern architecture in this sense largely remained the preserve of European architects until the 1960s, one notable exception being Le Groupe Transvaal in South Africa, which built homes inspired by Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier.

Post-colonial architecture

A number of new cities were built following the end of colonialism, while others were greatly expanded. Perhaps the best known example is that of Abidjan, where the majority of buildings were still designed by high-profile non-African architects. In Yamoussoukro, the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro is an example of a desire for monumentality in these new cities, but Arch 22 in the old Gambian capital of Banjul displays the same bravado.

Experimental designs have also appeared, most notably the Eastgate Centre in Zimbabwe. With an advanced form of natural air-conditioning, this building was designed to respond precisely to Harare's climate and needs, rather than import less suitable designs. Neo-vernacular architecture continues, for instance with the Great Mosque of Niono or Hassan Fathy's New Gourna.

Other notable structures of recent years have been some of the world's largest dams. The Aswan High Dam and Akosombo Dam hold back the world's largest reservoirs. In recent years, there has also been renewed bridge building in many nations, while the Trans-Gabon Railway is perhaps the last of the great railways to be constructed.

References

- Eglash, Ron (1999). African Fractals Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. ISBN 978-0-8135-2613-3.

- "Greniers collectifs - Patrimoine de l'Anti Atlas au Maroc | Holidway Maroc". Holidway (in French). 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Davidson, Basil (1995). Africa in History. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-684-82667-7.

- "Collective Granaries, Morocco". Global Heritage Fund. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Nijst, A. L. M. T. (1973). Living on the edge of the Sahara: a study of traditional forms of habitation and types of settlement in Morocco. Govt. Pub. Office.

- Bianchi, Robert Steven (2004). Daily Life of the Nubians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-313-32501-4.

- Bietak, Manfred. The C-Group culture and the Pan Grave culture Archived May 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Cairo: Austrian Archaeological Institute

- Kendall, Timothy. The 25th Dynasty Archived April 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Nubia Museum Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine: Aswan

- Kendall, Timothy. The Meroitic State: Nubia as a Hellenistic African State. 300 B.C.-350 AD Archived April 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Nubia Museum Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine:Aswan

- Prof. James Giblin, Department of History, The University of Iowa. Issues in African History Archived April 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Munson, Patrick J. (1980). "Archaeology and the prehistoric origins of the Ghana empire". The Journal of African History. 21 (4): 457–466. doi:10.1017/S0021853700018685.

- Holl, Augustin F.C. (2009). "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, (ca. 4000–2300 BP)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 341 (8–9): 703–712. Bibcode:2009CRGeo.341..703H. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005.

- Fage, J.D.; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1978). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- African indigenous knowledge and the sciences : journeys into the past and present. Emeagwali, Gloria T.,, Shizha, Edward. Rotterdam. 2016-07-08. ISBN 9789463005159. OCLC 953458729.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Asomani-Boateng, Raymond (2011-11-01). "Borrowing from the past to sustain the present and the future: indigenous African urban forms, architecture, and sustainable urban development in contemporary Africa". Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. 4 (3): 239–262. doi:10.1080/17549175.2011.634573. ISSN 1754-9175. S2CID 144469644.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Sukur Cultural Landscape". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Osasona, Cordelia O., From traditional residential architecture to the vernacular: the Nigerian experience (PDF), Ile-Ife, Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University, retrieved 3 December 2019

- Donald Routledge Hill (1996), "Engineering", p. 766, in (Rashed & Morelon 1996, pp. 751–95)

- Stewart, Courtney Ann. "Art and Architecture of Morocco and Muslim Spain: Bronze Age to Idrisid Dynasty". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ruggles, D. (1999-04-22). "D. Fairchild Ruggles. Review of "The Minbar from Kutubiyya Mosque" by Jonathan M. Bloom". Caa.reviews. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.1999.75. ISSN 1543-950X.

- Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062455-2.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020-06-30). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21870-1.

- Soo-Hoo, Anna. ""A Very Sweet Present: Moroccan Sugar Loaves" by Iziar de Miguel". Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Man, God and Civilization pg 216

- Diriye, p.102

- Historical Society of Ghana. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, The Society, 1957, pp81

- Davidson, Basil. The Lost Cities of Africa. Boston: Little Brown, 1959, pp86

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. pp. 123–126. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Wesler,Kit W.(1998). Historical archaeology in Nigeria. Africa World Press pp.143,144 ISBN 9780865436107.

- Pearce, Fred. African Queen. New Scientist, 11 September 1999, Issue 2203.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Birmingham, David (1981). Central Africa to 1870 Zambezia, Zaire and the South Atlantic. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-521-28444-8.

- Davidson, Basil (1991). African Civilization Revisiteed From Antiquity to Modern Times. pp. 343–344. ISBN 978-0-86543-124-9.

- Hull, Richard W. (1976). African Cities and Towns Before the European Conquest. New York : Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05581-8.

- Shillington, Kevin (2004). Encyclopedia of African history. p. 1368. ISBN 978-1-57958-453-5.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Tracy, James D. (2000). City Walls The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine (2005). The History of African Cities South of the Sahara From the Origins to Colonization. Markus Wiener Pub. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-55876-303-6.

- Grossmann, Peter. Christian Nubia and Its Churches Archived May 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Cairo: German Archaeological Institute

- Shinnie, P.L. Medieval Nubia. Khartoum:Sudan Antiquities Service,1954

- African Archaeological Review, Volume 15, Number 3, September 1998 , pp. 199-218(20)

- Jona Schellekens, "Dutch Origins of South-African Colonial Architecture," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 56 (1997), pp. 204–206.

- Ireland, Jeannie (2009). History of Interior Design. Fairchild Books & Visuals. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-56367-462-4.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). History of Africa, Revised 2nd Edition. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-333-59957-0.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). History of Africa, Revised 2nd Edition. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-333-59957-0.

- Iliffe, John (2007). Africans The History of a Continent. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-521-68297-8.

- Acquier, Jean-Louis. Architectures de Madagascar. Paris: Berger-Levrault.

- Tracy, James D. (2000). City Walls The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6.

- Jiménez-Vicario, Pedro Miguel; García-Martínez, Pedro; Ródenas-López, Manuel Alejandro (2018-07-03). "The influence of North African and Middle Eastern architectures in the birth and development of modern architecture in Central Europe (1898–1937)". Mediterranean Historical Review. 33 (2): 179–198. doi:10.1080/09518967.2018.1535394. ISSN 0951-8967.

- Dahmani, Iman; El moumni, Lahbib; Meslil, El mahdi (2019). Modern Casablanca Map. Translated by Borim, Ian. Casablanca: MAMMA Group. ISBN 978-9920-9339-0-2.

- جديد, الدار البيضاء-العربي. "إيلي أزاجوري.. استعادة عميد المعماريين المغاربة". alaraby (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- Dahmani, Iman; El moumni, Lahbib; Meslil, El mahdi (2019). Modern Casablanca Map. Translated by Borim, Ian. Casablanca: MAMMA Group. ISBN 978-9920-9339-0-2.

- "Adaptations of Vernacular Modernism in Casablanca". Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- Hofbauer, Lucy (2010-07-01). "Transferts de modèles architecturaux au Maroc. L'exemple de Jean-François Zévaco, architecte (1916-2003)". Les Cahiers d'EMAM. Études sur le Monde Arabe et la Méditerranée (in French) (20): 71–86. doi:10.4000/emam.77. ISSN 1969-248X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of Africa. |