Indian Ocean slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade, sometimes known as the East African slave trade, was multi-directional slave trade and has changed over time. Africans were sent as slaves to the Middle East, to Indian Ocean islands (including Madagascar), to the Indian subcontinent, and later to the Americas.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Early Indian Ocean slave trade

Slave trading in the Indian Ocean goes back to 2500 BCE.[3] Ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Indians and Persians all traded slaves on small scale across the Indian Ocean (and sometimes the Red Sea).[4] Slave trading in the Red Sea around the time of Alexander the Great is described by Agatharchides.[4] Strabo's Geographica (completed after 23 CE) mentions Greeks from Egypt trading slaves at the port of Adulis and other ports on the Somali coast.[5] Pliny the Elder's Natural History (published in 77 CE) also describes Indian Ocean slave trading.[4] In the 1st century CE, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea advised of slave trading opportunities in the region, particularly in the trading of "beautiful girls for concubinage."[4] According to this manual, slaves were exported from Omana (likely near modern-day Oman) and Kanê to the west coast of India.[4] The ancient Indian Ocean slave trade was enabled by building boats capable of carrying large numbers of human beings in the Persian Gulf using wood imported from India. These shipbuilding activities go back to Babylonian and Achaemenid times.[6]

Gujarati merchants evolved into the first explorers of the Indian Ocean as they traded slaves as well as other African goods such as ivory and tortoise shells. The Guajaratis were participants in the slavery business at Nairobi, Mombasa, Zanzibar and to some extent on the South African region.[7] Indonesians also participants, they brought spices to Africa's shores, they would have returned via India and Sri Lanka with ivory, iron, skins, and slaves.[8]

After the involvement of the Byzantine Empire and Sassanian Empire in slave trading in the 1st century, it became a major enterprise.[4] Cosmas Indicopleustes wrote in his Christian Topography (550 CE) that slaves captured in Ethiopia would be imported into Byzantine Egypt via the Red Sea.[5] He also mentioned the import of eunuchs by the Byzantines from Mesopotamia and India.[5] After the 1st century, the export of black Africans became a "constant factor".[6] Under the Sassanians, Indian Ocean trade was used not just to transport slaves, but also scholars and merchants.[4]

Muslim Period

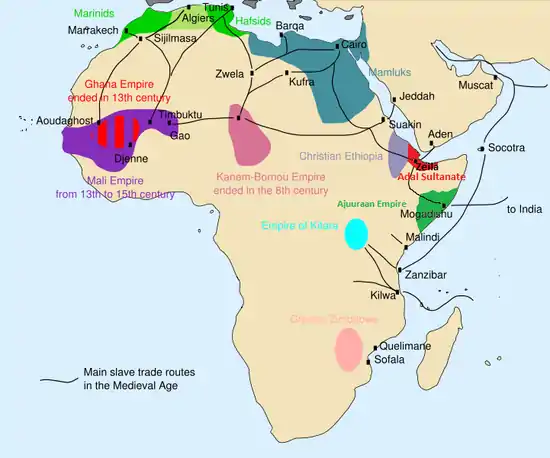

Exports of slaves to the Muslim world from the Indian Ocean began after Muslim Arab and Swahili traders won control of the Swahili Coast and sea routes during the 9th century (see Sultanate of Zanzibar). These traders captured Bantu peoples (Zanj) from the interior in the present-day lands of Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania and brought them to the coast.[9][10] There, the slaves gradually assimilated in the rural areas, particularly on the Unguja and Pemba islands.[11] Muslim merchants traded an estimated 1000 African slaves annually between 800 and 1700, a number that grew to c. 4000 during the 18th century, and 3700 during the period 1800–1870.[12]

William Gervase Clarence-Smith writes that estimating the number of slaves traded has been controversial in the academic world, especially when it comes to the slave trade in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea.[13] When estimating the number of people enslaved from East Africa, author N'Diaye and French historian Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau[14][15] estimate 17 million as the total number of people transported from the 7th century until 1920, amounting to an average of 6,000 people per year. Many of these slaves were transported by the Indian Ocean and Red Sea via Zanzibar.[16] Historian Lodhi challenged the 17 million figure by arguing that the total population of Africa "at that time" was less than 40 million.[17]

The captives were sold throughout the Middle East. This trade accelerated as superior ships led to more trade and greater demand for labour on plantations in the region. Eventually, tens of thousands of captives were being taken every year.[11][18][19]

Slave labor in East Africa was drawn from the Zanj, Bantu peoples that lived along the East African coast.[10][20] The Zanj were for centuries shipped as slaves by Muslim traders to all the countries bordering the Indian Ocean. The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs recruited many Zanj slaves as soldiers and, as early as 696, there were revolts of Zanj slave soldiers in Iraq.[21] A 7th-century Chinese text mentions ambassadors from Java presenting the Chinese emperor with two Seng Chi (Zanj) slaves as gifts in 614, and 8th- and 9th-century chronicles mention Seng Chi slaves reaching China from the Hindu kingdom of Sri Vijaya in Java.[21]

The Zanj Rebellion, a series of uprisings that took place between 869 and 883 AD near the city of Basra (also known as Basara), situated in present-day Iraq, is believed to have involved enslaved Zanj that had originally been captured from the African Great Lakes region and areas further south in East Africa.[22] It grew to involve over 500,000 slaves and free men who were imported from across the Muslim empire and claimed over "tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq".[23] The Zanj who were taken as slaves to the Middle East were often used in strenuous agricultural work.[24] As the plantation economy boomed and the Arabs became richer, agriculture and other manual labor work was thought to be demeaning. The resulting labor shortage led to an increased slave market.

It is certain that large numbers of slaves were exported from eastern Africa; the best evidence for this is the magnitude of the Zanj revolt in Iraq in the 9th century, though not all of the slaves involved were Zanj. There is little evidence of what part of eastern Africa the Zanj came from, for the name is here evidently used in its general sense, rather than to designate the particular stretch of the coast, from about 3°N. to 5°S., to which the name was also applied.[25]

The Zanj were needed to take care of:

the Tigris-Euphrates delta, which had become abandoned marshland as a result of peasant migration and repeated flooding, could be reclaimed through intensive labor. Wealthy proprietors "had received extensive grants of tidal land on the condition that they would make it arable." Sugar cane was prominent among the products of their plantations, particularly in Khūzestān Province. Zanj also worked the salt mines of Mesopotamia, especially around Basra.[26]

Their jobs were to clear away the nitrous topsoil that made the land arable. The working conditions were also considered to be extremely harsh and miserable. Many other people were imported into the region, besides Zanj.[27]

Historian M. A. Shaban has argued that rebellion was not a slave revolt, but a revolt of blacks (zanj). In his opinion, although a few runaway slaves did join the revolt, the majority of the participants were Arabs and free Zanj. If the revolt had been led by slaves, they would have lacked the necessary resources to combat the Abbasid government for as long as they did.[28]

In Somalia, the Bantu minorities are descended from Bantu groups that had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon. To meet the demand for menial labor, Bantus from southeastern Africa captured by Somali slave traders were sold in cumulatively large numbers over the centuries to customers in Somalia and other areas in Northeast Africa and Asia.[29] People captured locally during wars and raids were also sometimes enslaved by Somalis mostly of Oromo and Nilotic origin.[30][31][32] However, the perception, capture, treatment and duties of both groups of slaves differed markedly.[32][33] From 1800 to 1890, between 25,000 and 50,000 Bantu slaves are thought to have been sold from the slave market of Zanzibar to the Somali coast.[34] Most of the slaves were from the Majindo, Makua, Nyasa, Yao, Zalama, Zaramo and Zigua ethnic groups of Tanzania, Mozambique and Malawi. Collectively, these Bantu groups are known as Mushunguli, which is a term taken from Mzigula, the Zigua tribe's word for "people" (the word holds multiple implied meanings including "worker", "foreigner", and "slave").[35]

During the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century, slaves shipped from Ethiopia had a high demand in the markets of the Arabian peninsula and elsewhere in the Middle East. They were mostly domestic servants, though some served as agricultural labourers, or as water carriers, herdsmen, seamen, camel drivers, porters, washerwomen, masons, shop assistants and cooks. The most fortunate of the men worked as the officials or bodyguards of the ruler and emirs, or as business managers for rich merchants.[36] They enjoyed significant personal freedom and occasionally held slaves of their own. Besides European, Caucasian, Javanese and Chinese girls brought in from the Far East, "red" (non-black) Ethiopian young females were among the most valued concubines. The most beautiful ones often enjoyed a wealthy lifestyle, and became mistresses of the elite or even mothers to rulers.[36] The principal sources of these slaves, all of whom passed through Matamma, Massawa and Tadjoura on the Red Sea, were the southwestern parts of Ethiopia, in the Oromo and Sidama country.[37]

European Period

Slave trade also occurred in the eastern Indian Ocean before the Dutch settled there around 1600 but the volume of this trade is unknown.[38] European slave trade in the Indian Ocean began when Portugal established Estado da Índia in the early 16th century. From then until the 1830s, c. 200 slaves were exported from Mozambique annually and similar figures has been estimated for slaves brought from Asia to the Philippines during the Iberian Union (1580–1640).

The establishment of the Dutch East India Company in the early 17th century lead to a quick increase in volume of the slave trade in the region; there were perhaps up to 500,000 slaves in various Dutch colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries in the Indian Ocean. For example, some 4000 African slaves were used to build the Colombo fortress in Dutch Ceylon. Bali and neighbouring islands supplied regional networks with c. 100,000–150,000 slaves 1620–1830. Indian and Chinese slave traders supplied Dutch Indonesia with perhaps 250,000 slaves during 17th and 18th centuries.[38]

The East India Company (EIC) was established during the same period and in 1622 one of its ships carried slaves from the Coromandel Coast to Dutch East Indies. The EIC mostly traded in African slaves but also some Asian slaves purchased from Indian, Indonesian and Chinese slave traders. The French established colonies on the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in 1721; by 1735 some 7,200 slaves populated the Mascarene Islands, a number which had reached 133,000 in 1807. The British captured the islands in 1810, however, and because the British had prohibited the slave trade in 1807 a system of clandestine slave trade developed to bring slaves to French planters on the islands; in all 336,000–388,000 slaves were exported to the Mascarane Islands from 1670 until 1848.[38]

In all, Europeans traders exported 567,900–733,200 slaves within the Indian Ocean between 1500 and 1850 and almost that same amount were exported from the Indian Ocean to the Americas during the same period. Slave trade in the Indian Ocean was, nevertheless, very limited compared to c. 12,000,000 slaves exported across the Atlantic.[38][12] Some 200,000 slaves were sent in the 19th century to European plantations in the Western Indian Ocean.[39]

Geography and transportation

From the evidence of illustrated documents, and travellers' tales, it seems that people travelled on dhows or jalbas, Arab ships which were used as transport in the Red Sea. Crossing the Indian Ocean required better organisation and more resources than overland transport. Ships coming from Zanzibar made stops on Socotra or at Aden before heading to the Persian Gulf or to India. Slaves were sold as far away as India, or even China: there was a colony of Arab merchants in Canton. Serge Bilé cites a 12th-century text which tells us that most well-to-do families in Canton, China had black slaves. Although Chinese slave traders bought slaves (Seng Chi i.e. the Zanj[21]) from Arab intermediaries and "stocked up" directly in coastal areas of present-day Somalia, the local Somalis—referred to as Baribah and Barbaroi (Berbers) by medieval Arab and ancient Greek geographers, respectively (see Periplus of the Erythraean Sea),[20][40][41] and no strangers to capturing, owning and trading slaves themselves[42]—were not among them.[43]

One important commodity being transported by dhows to Somalia was slaves from other parts of East Africa. During the nineteenth century, the East African slave trade grew enormously due to demands by Arabs, Portuguese, and French. Slave traders and raiders moved throughout eastern and central Africa to meet this rising demand. The Bantus inhabiting Somalia are descended from Bantu groups that had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon, and whose members were later captured and sold by traders.[33] The Bantus are ethnically, physically, and culturally distinct from Somalis, and they have remained marginalized ever since their arrival in Somalia.[44][45]

Towns and ports involved

|

References

- "Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades". obo. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Harries, Patrick. "The story of East Africa's role in the transatlantic slave trade". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. p. 78.

The “globalized” Indian Ocean trade in fact has substantially earlier, even pre-Islamic, global roots. These roots extend back to at least 2500 BCE, suggesting that the so-called “globalization” of the Indian Ocean trading phenomena, including slave trading, was in reality a development that was built upon the activities of pre-Islamic Middle Eastern empires, which activities were in turn inherited, appropriated, and improved upon by the Muslim empires that followed them, and then, after that, they were again appropriated, exploited, and improved upon by Western European interveners.

- Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. pp. 79–80.

- Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. pp. 82–83.

- Freamon, Bernard K. Possessed by the Right Hand: The Problem of Slavery in Islamic Law and Muslim Cultures. Brill. pp. 81–82.

- "'Even British were envious of Gujaratis' - Times Of India". web.archive.org. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Beale, Philip. "From Indonesia to Africa:Borobudur Ship Expedition" (PDF).

- Ochieng', William Robert (1975). Eastern Kenya and Its Invaders. East African Literature Bureau. p. 76. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Bethwell A. Ogot, Zamani: A Survey of East African History, (East African Publishing House: 1974), p.104

- Lodhi, Abdulaziz (2000). Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. p. 17. ISBN 978-9173463775.

- Copied content from Indian Ocean; see that page's history for attribution.

- William Gervase Clarence-Smith (2013). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. p. 1.

- Lacoste, Yves (2005). "Hérodote a lu : Les Traites négrières, essai d'histoire globale, de Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau" [Book Review: African Slave Trade, an Attempted Global History, by Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau]. Hérodote (in French) (117): 196–205. doi:10.3917/her.117.0193. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Pétré-Grenouilleau, Olivier (2004). Les Traites négrières, essai d'histoire globale [African Slave Trade, an Attempted Global History] (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 9782070734993.

- "Focus on the slave trade". BBC. 3 September 2001. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- "East Africa's forgotten slave trade". Deutsche Welle. 22 August 2019.

- John Donnelly Fage and William Tordoff (December 2001). A History of Africa (4 ed.). Budapest: Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 9780415252485.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Tannenbaum, Edward R.; Dudley, Guilford (1973). A History of World Civilizations. Wiley. p. 615. ISBN 978-0471844808.

- F.R.C. Bagley et al., The Last Great Muslim Empires, (Brill: 1997), p.174

- Roland Oliver (1975). Africa in the Iron Age: c.500 BC-1400 AD (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780521099004.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 585. ISBN 978-0313332739.

- Asquith, Christina. "Revisiting the Zanj and Re-Visioning Revolt: Complexities of the Zanj Conflict – 868-883 Ad – slave revolt in Iraq". Questia.com. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "Islam, From Arab To Islamic Empire: The Early Abbasid Era". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Talhami, Ghada Hashem (1 January 1977). "The Zanj Rebellion Reconsidered". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 10 (3): 443–461. doi:10.2307/216737. JSTOR 216737.

- "the Zanj: Towards a History of the Zanj Slaves' Rebellion". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "Hidden Iraq". William Cobb.

- Shaban 1976, pp. 101-02.

- Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p.ix

- Meinhof, Carl (1979). Afrika und Übersee: Sprachen, Kulturen, Volumes 62-63. D. Reimer. p. 272.

- Bridget Anderson, World Directory of Minorities, (Minority Rights Group International: 1997), p. 456.

- Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 116.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refugees Vol. 3, No. 128, 2002 UNHCR Publication Refugees about the Somali Bantu" (PDF). Unhcr.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Refugee Reports, November 2002, Volume 23, Number 8

- Campbell, Gwyn (2004). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0203493021.

- Clarence-Smith, edited by William Gervase (1989). The Economics of the Indian Ocean slave trade in the nineteenth century (1. publ. in Great Britain. ed.). London, England: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0714633596.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Allen 2017, Slave Trading in the Indian Ocean: An Overview, pp. 295–299

- William Gervase Clarence-Smith (2013). The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. p. 10. ISBN 9781135182144.

- Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.13

- James Hastings, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 12: V. 12, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2003), p.490

- Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1746

- David D. Laitin, Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience, (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.52

- cite web |url=http://webdev.cal.org/development/co/bantu/sbpeop.html%5B%5D |title=The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture – People |publisher=Cal.org |accessdate=21 February 2013 dead link|date=May 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes

- L. Randol Barker et al., Principles of Ambulatory Medicine, 7 edition, (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2006), p.633