Maghrebi script

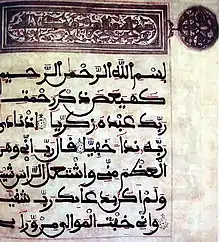

Maghrebi (or Maghribi) script (Arabic: الخط المغربي) refers to a loosely related family of Arabic scripts that developed in the Maghreb (North Africa), al-Andalus (Iberia), and Biled as-Sudan (the West African Sahel). Maghrebi script is influenced by Kufic letters,[1] and is traditionally written with a pointed tip (القلم المذبب), producing a line of even thickness.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

The script is characterized by rounded letter forms, extended horizontal features, and final open curves below the baseline.[3] It also differs from Mashreqi scripts in the notation of the letters faa' (Maghrebi: ڢ ; Mashreqi: ف) and qoph (Maghrebi: ڧ ; Mashreqi: ق).[4]

For centuries, Maghrebi script was used to write Arabic manuscripts and record Andalusi and Moroccan literature, whether in Standard Arabic, Maghrebi Arabic, or Amazigh languages.

History

Origins

Arabic script first came to the Maghreb with the Islamic conquests (643–709).[5] The conquerors, led by Uqba ibn Nafi, used both Hijazi and Kufic scripts, as demonstrated in coins minted in 711 under Musa ibn Nusayr.[6] Maghrebi script is a direct descendant of the old Kufic script that predated Ibn Muqla's al-khat al-mansub (الخَط المَنْسُوب proportioned line) standardization reforms, which affected Mashreqi scripts.[2] The Arabic script in its Iraqi Kufic form spread from centers such as Fes, Cordoba, and Qairawan throughout the region along with Islam, as the Quran was studied and transcribed.[2][6] Qairawani Kufic script developed in Qairawan from the Iraqi Kufic script.[6]

African and Andalusi scripts

Early on, there were two schools of Maghrebi script: the African script (الخط الإفريقي) and the Andalusi script (الخط الأندلسي).[6] The African script evolved in North Africa from Iraqi Kufic by way of the Kufic of Qairawan.[6] The Andalusi script evolved in Iberia from the Damascene Kufic script with the establishment of the second Umayyad state, which would become the Caliphate of Córdoba.[6] The Andalusi script was particular for its rounded letters, as attested to in Al-Maqdisi's geography book The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions.[6] The African script had spread throughout the Maghreb before the spread of the Andalusi script.[6] One of the most famous early users of the Arabic script was Salih ibn Tarif, the leader of the Barghawata Confederacy and the author of a religious text known as the Quran of Salih.[6][7]

In al-Maghreb al-Aqsa ("the Far West," Morocco), the script developed independently from the Kufic of the Maghrawa and Bani Ifran under the Idrisid dynasty (788-974);[6] it gained Mashreqi features under the Imam Idris I, who came from Arabia.[6] The script under the Idrisids was basic and unembellished; it was influenced by Iraqi Kufic, which was used on the Idrisid dirham.[6]

Almoravid

_mint.jpg.webp)

Under the Almoravid dynasty, the Andalusi script spread throughout the Maghreb, reaching Qairawan; the Jerīd region, however, kept the African script.[6] A version of Kufic with florid features developed at this time.[8] The University of al-Qarawiyyin, the Almoravid Qubba, and the Almoravid Minbar bear examples of Almoravid Kufic.[9][10]

The Kufic script of the Almoravid dinar was imitated in a maravedí issued by Alfonso VIII of Castile.[11][12]

The minbar of the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque, created in 1144, was the "last major testament of Almoravid patronage," and features what is now called Maghrebi thuluth, an interpretation of Eastern thuluth and diwani traditions.[13]

Almohad

Under the Almohad dynasty, Arabic calligraphy continued to flourish and a variety of distinct styles developed.[6] The Almohad caliphs, many of whom were themselves interested in Arabic script, sponsored professional calligraphers, inviting Andalusi scribes and calligraphers to settle in Marrakesh, Fes, Ceuta, and Rabat.[6][13] The Almohad caliph Abu Hafs Umar al-Murtada established the first public manuscript transcription center at the madrasa of his mosque in Marrakesh (now the Ben Youssef Madrasa).[6][14]

The Maghrebi thuluth script was appropriated and adopted as an official "dynastic brand" used in different media, from manuscripts to coinage to fabrics.[13] The Almohads also illuminated certain words or phrases for emphasis with gold leaf and lapis lazuli.[13]

For centuries, the Maghrebi script was used to write Arabic manuscripts that were traded throughout the Maghreb.[15] According to Muhammad al-Manuni, there were 104 paper mills in Fes under the reign of Yusuf Ibn Tashfin in the 11th century, and 400 under the reign of Sutlan Yaqub al-Mansur in the 12th century.[16]

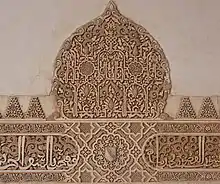

Nasrid

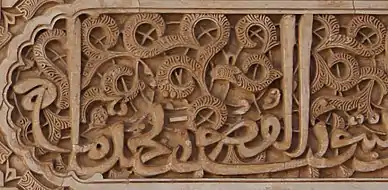

In the Emirate of Granada under the Nasrid dynasty, and particularly under Yusuf I and Muhammad V, Arabic epigraphy further developed.[17] Kufic inscriptions developed extended vertical strokes forming ribbon-like decorative knots.[17] Kufic script also had "an enormous influence on the decorative and graphic aspects of Christian art."[17]

"And the peninsula was conquered with the sword"

"They build palaces diligently"

Aljamiado

In Iberia, the Arabic script was used to write Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Portuguese, Spanish or Ladino.[19] This writing system was referred to as Aljamiado, from ʿajamiyah (عجمية).[20]

Fesi Andalusi script

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Waves of migration from Iberia throughout the history of al-Andalus impacted writing styles in North Africa. Ibn Khaldun noted that the Andalusi script further developed under the Marinid dynasty (1244–1465), when Fes received Andalusi refugees.[6] In addition to Fes, the script flourished in cities such as Ceuta, Taza, Meknes, Salé, and Marrakesh, although the script experienced a regression in rural areas far from the centers of power.[6] The Fesi script spread throughout much of the Islamic west. Octave Houdas gives the exception of the region around Algiers, which was more influenced by the African script of Tunisia.[6] Muhammad al-Manuni noted that Maghrebi script essentially reached its final form during the Marinid period, as it became independent of the Andalusi script.[6] There were three forms of Maghrebi script in use: one in urban centers such as those previously mentioned, one in rural areas used to write in both Arabic and Amazigh languages, and one that preserved Andalusi features.[6] Maghrebi script was also divided into different varieties: Kufic, mabsūt, mujawhar, Maghrebi thuluth, and musnad (z'mami).[6]

Saadi reforms

The reforms in the Saadi period (1549-1659) affected manuscript culture and calligraphy.[6] The Saadis founded centers for learning calligraphy, including the madrasa of the Mouassine Mosque, which was directed by a dedicated calligrapher as was the custom in the Mashreq.[6] Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur himself was proficient in Maghrebi thuluth, and even invented a secret script for his private correspondences.[6] Decorative scripts flourished under the Saadi dynasty and were used in architecture, manuscripts, and coinage.[6]

Alawite

Maghrebi script was supported by the 17th-century Alawite sultans Al-Rashid and Ismail.[6] Under the reign of Sultan Muhammad III, the script devolved into an unrefined, illegible badawi script (الخط البدوي) associated with rural areas.[21][15] Under Sultan Suleiman, the script improved in urban areas and particularly in the capital Meknes.[6] Meanwhile, Rabat and Salé preserved some features of Andalusi script, and some rural areas such as Dukāla, Beni Zied, and al-Akhmas excelled in the Maghrebi script.[6]

The script quality then regressed again, which led Ahmed ibn Qassim ar-Rifā'ī ar-Ribātī to start a script reform and standardization movement as Ibn Muqla and Ibn al-Bawwab had done in the Mashriq.[6] He authored Stringing the Pearls of the Thread (نظم لآلئ السمط في حسن تقويم بديع الخط), a book in the form of an urjuza on the rules of Maghrebi script.[6][22]

Muhammad Bin Al-Qasim al-Qundusi, active in Fes from 1828–1861, innovated a unique style known as al-Khatt al-Qundusi (الخط القندوسي).[17]

After Muhammad at-Tayib ar-Rudani introduced the first Arabic lithographic printing press to Morocco in 1864, the mujawher variety of the Maghrebi script became the standard for printing body text, although other varieties were also used.[23][6]

The French Protectorate in Morocco represented a crisis for Maghrebi script, as Latin script became dominant in education and public life, and the Moroccan Nationalist Movement fought to preserve Maghrebi script in response.[6] In 1949, Muhammad bin al-Hussein as-Sūsī and Antonio García Jaén published Ta'līm al-Khatt al-Maghrebi (تعليم الخط المغربي) a series of five booklets teaching Maghrebi script printed in Spain.[24][25][26]

Recently

In 2007, Muḥammad al-Maghrāwī and Omar Afa cowrote Maghrebi Script: History, Present, and Horizons (الخط المغربي: تاريخ وواقع وآفاق).[27][28] The following year, the Muhammad VI Prize for the Art of Maghrebi Script, organized by the Moroccan Ministry of Islamic Affairs, was announced.[29][30]

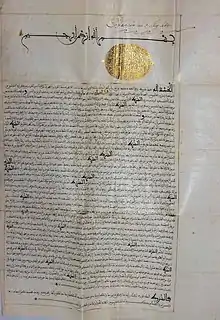

In early 2020, the President of Tunisia, Kais Saied, garnered significant media attention for his handwritten official letters in the Maghrebi script.[31][32]

Variations

In the book al-Khat al-Maghrebi, five main subscripts of Maghrebi script are identified:[33]

- Maghrebi Kufic (كوفي مغربي) variations of Kufic script used in the Maghreb and al-Andalus.

- Almoravid Kufic (كوفي مرابطي)[34] a decorative script that does not receive Arabic diacritics. It was used in coin minting and is usually accompanied by fine floral designs.[35] The Almoravid minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakesh features a fine example.

- Almohad Kufic (كوفي موحدي)

- Marinid Kufic (كوفي مريني)

- Alawite Kufic (كوفي علوي)

- Qayrawani Kufic (كوفي قيرواني)

- Pseudo Kufic (شبه كوفي)

- Mabsout (مبسوط) script, used for body text and to write the Quran, similar in usage to the eastern Naskh.[36]

- Andalusi Mabsout

- Saadi Mabsout

- Alawite Mabsout

A hand-drawn phrase in Maghrebi mabsout. It reads: "الخط الحسن يزيد الحق وضوحا" which means something similar to "A fine line increases the truth in clarity."

A hand-drawn phrase in Maghrebi mabsout. It reads: "الخط الحسن يزيد الحق وضوحا" which means something similar to "A fine line increases the truth in clarity."

- Mujawher (مجوهر) cursive script, mainly used by the king to announce laws.[36] This is the script that was used for body text when lithographic prints started to be produced in Fes.[23]

- Thuluth Maghrebi (ثلث مغربي) script, formerly called Mashreqi (مشرقي) or Maghrebized Mashreqi (مشرقي متمغرب) a script inspired by the Mashreqi Thuluth script.[36] It is mainly used as a decorative script for book titles and walls in mosques. It was used as an official script by the Almohads.[13]

- Musnad (مسند) script, or Z'mami (زمامي) script, a cursive script mainly used by courts and notaries in writing marriage contracts.[37] This script is derived from Mujawher, and its letters in this script lean to the right.[37] Because is difficult to read, this script was used to write texts that the author wanted to keep obscure, such as texts about sorcery.

In addition, Muhammad Bin Al-Qasim al-Qundusi, a 19th-century Sufi calligrapher based in Fes, developed a flamboyant style now known as Qandusi (قندوسي) script.[38]

Among the publications of Octave Houdas, a 19th-century French orientalist, dealing with the subject of Maghrebi script, there are Essai sur l'Ecriture Maghrebine (1886)[1] and Recueil de Lettres Arabes Manuscrites (1891).[39] In 1886, he identified 4 main subscripts within the Maghrebi script family:[40]

West African Maghrebi scripts

.jpg.webp)

Various West African Arabic scripts, also called Sudani scripts (in reference to Bilad as-Sudan), also fall under the category of Maghrebi scripts, including:

- Suqi (سوقي) named after the town of Suq, though also used in Timbuktu. It is associated with the Tuareg people.[40]

- Fulani (فولاني)

- Hausawi (هاوساوي)

- Mauretanian Baydani (بيضاني موريطاني)

- Kanemi (كنيمي) or Kanawi, is associated with the region of Kano in modern-day Chad and northern Nigeria, associated with Borno—also Barnawi script[40]

- Saharan[40][41]

Suqi script

Suqi script Fulani script

Fulani script Hausawi script

Hausawi script Baydani script

Baydani script Kanemi script

Kanemi script

Contrast with Mashreqi scripts

One of the prominent ways Maghrebi scripts differ from scripts of the Arabic-speaking East is the dotting of the letters faa' (ف) and qoph (ق). In eastern tradition, the faa' is represented by a circle with a dot above, while in Maghrebi scripts the dot goes below the circle (ڢ).[4] In eastern scripts, the qoph is represented by a circle with two dots above it, whereas the Maghrebi qoph is a circle with just one dot above (ڧ), similar to the eastern faa'.[4] In fact, concerns over the preservation of Maghrebi writing traditions played a part in the reservations of the Moroccan ulama's against importing the printing press.[42]

Gallery

- Qurans in Maghrebi scripts

Blue Qur'an, 9th to early 10th-century, from either al-Andalus or Tunisia.[43]

Blue Qur'an, 9th to early 10th-century, from either al-Andalus or Tunisia.[43]

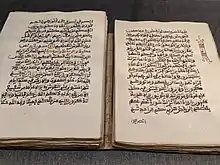

Moroccan Quran from around 1300.[46]

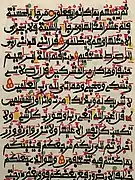

Moroccan Quran from around 1300.[46] Andalusi Quran, late 13th–early 14th century.[47]

Andalusi Quran, late 13th–early 14th century.[47]

17th or 18th century Moroccan Quran

17th or 18th century Moroccan Quran 18th century Moroccan Quran.[47]

18th century Moroccan Quran.[47]

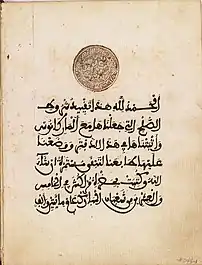

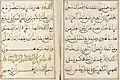

Quran in mabsūt script

Quran in mabsūt script

References

- Houdas, Octave (1886). Essai sur l'écriture maghrebine [Essay on Maghrebi writing] (in French). Paris, France: École des langues orientales vivantes.

- van de Boogert, N. (1989). "Some notes on Maghribi script" (PDF). Manuscripts of the Middle East. ISSN 0920-0401. OCLC 615561724.

- document, doi:10.1107/s1600576719010537/ks5620sup6.exe

- al-Banduri, Muhammad (2018-11-16). "الخطاط المغربي عبد العزيز مجيب بين التقييد الخطي والترنح الحروفي" [Moroccan calligrapher Abd al-Aziz Mujib: between calligraphic restriction and alphabetic staggering]. Al-Quds (in Arabic). Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- Al-Khitaat, Khaled Muhammad Al-Masri (2014-01-01). مرجع الطلاب في الخط العربي [Student Reference in Arabic Calligraphy] (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiya. ISBN 978-2-7451-3523-0.

- Hajji, Muhammad (2000). معلمة المغرب : قاموس مرتب على حروف الهجاء يحيط بالمعارف المتعلقة بمختلف الجوانب التاريخية والجغرافية والبشرية والحضارية للمغرب الاقصى : بيبليوغرافيا الاجزاء الاثني عشر المنشورة [Teacher of Morrocco: An Alphabetical Dictionary of the History, Geography, People, and Civilization of al-Maghreb al-Aqsa]. Maṭābiʻ Salā. p. 3749. OCLC 49744368.

- Yusri, Muhammad (2018-11-12). "دولة برغواطة في المغرب... هراطقة كفار أم ثوار يبحثون عن العدالة؟" [The Barghawata state in Morocco...heretical kafirs or revolutionaries searching for justice?]. Rasif 22 (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Qantara - The Almoravid dynasty (1056-1147)". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Toufiq, Ahmed (March 1998). The Minbar from the Kutubiyya Mosque. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08637-9.

- Abu Zayd, Muhammad Omar (2017). مبادئ الخط الكوفي المغربي من العهد المرابطي [The principles of the Maghrebi Kufic script from the Almoravid era] (in Arabic). Kuwait: Kuwait Center for the Islamic Arts.

- "CNG: Feature Auction CNG 70. SPAIN, Castile. Alfonso VIII. 1158-1214. AV Maravedi Alfonsi-Dobla (3.86 g, 4h). Toledo (Tulaitula) mint. Dated Safar era 1229 (1191 AD)". www.cngcoins.com. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- "Coin - Portugal". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Bongianino, Umberto (Feb 8, 2018). The Ideological Power of Some Almohad Illuminated Manuscripts (Lecture).

- "المدارس المرينية: بين رغبة المخزن ومعارضة الفقهاء" [The Marinid Schools: Between the Desire for Preservation and the Oppostion of the Judges]. Zamane (in Arabic). 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- Krätli, Graziano; Lydon, Ghislaine (2011). The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18742-9.

- Sijelmassi, Mohamed (1987). Enluminures: Des Manuscripts Royaux au Maroc [Royal Illuminated Manuscripts of Morocco] (in French). ACR. ISBN 978-2-86770-025-5.

- Jayyusi, Salma Khadra; Marín, Manuela (1992). The Legacy of Muslim Spain. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-09599-1.

- محمد كرد علي, محمد بن عبد الرزاق بن محمد, 1876-1953. (2011). غابر الأندلس وحاضره [Old Andalus and Its Heritage] (in Arabic). Sharakat Nowabigh al-Fakr. ISBN 978-977-6305-97-7. OCLC 1044625566.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ribera, Julian; Gil, Pablo; Sanchez, Mariano (August 2018). Colección de Textos Aljamiados, Publicada Por Pablo Gil, Julián Ribera y Mariano Sanchez (in Spanish). Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-0-274-51465-6.

- Chejne, A.G. (1993): Historia de España musulmana. Editorial Cátedra. Madrid, Spain. Published originally as: Chejne, A.G. (1974): Muslim Spain: Its History and Culture. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, USA

- الخطاط, خالد محمد المصري (2014-01-01). مرجع الطلاب في الخط العربي (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية. ISBN 978-2-7451-3523-0.

- الخطاط, خالد محمد المصري (2014-01-01). مرجع الطلاب في الخط العربي (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية. ISBN 978-2-7451-3523-0.

- الرباطي, أحمد بن محمد بن قاسم الرفاعي الحسني (2013). صبري, د. محمد (ed.). نظم لآلئ السمط في حسن تقويم بديع الخط. Rabat, Morocco: منشورات وزارة الأوقاف والشؤون الإسلامية - المملكة المغربية: دار أبي رقراق للطباعة والنشر. ISBN 978-9954-601-24-2.

- السعيدي, الخبر-أحمد. "قراءة في كتاب "الخط المغربي"". إمواطن : رصد إخباري (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- العسري, كتبه: كريمة قاسم (2015-07-02). "المنجز الحضاري المغربي في الخط العربي". مشاهد 24 (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- García Jaén, Antonio; Al-Susi, Muhammad Ibn al-Husayn; Marruecos (Protectorado Español); Delegación de Educación y Cultura (1949). Tariq ta'lim al-jatt. Tetuán: Niyaba al-Tarbiya wa-l-Taqafa. OCLC 431924417.

- Nobili, Mauro (2011-06-03). "Arabic Scripts in West African Manuscripts: A Tentative Classification from the de Gironcourt Collection". Islamic Africa. 2 (1): 105–133. doi:10.5192/215409930201105. ISSN 2154-0993.

- افا، عمر; مغراوي، محمد (2007). الخط المغربي: تاريخ وواقع وآفاق (in Arabic). الدارالبيضاء: وزارة الأوقاف و الشؤون الاسلامية،. ISBN 978-9981-59-129-5. OCLC 191880956.

- "بالفيديو.. الخط العربي ببصمة نسائية مغربية.. روائع الماضي والحاضر". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "النظام القانوني لجائزة محمد السادس لفن الخط المغربي -". lejuriste.ma (in Arabic). 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "كتبها بخط يده.. رسالة سعيّد للجملي تثير مواقع التواصل (شاهد)". عربي21 (in Arabic). 2019-11-16. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- نت, العربية (2019-11-16). "بالصورة.. رسالة من الرئيس التونسي تشعل مواقع التواصل". العربية نت (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- أفا, عمر (2007). الخط المغربي: تاريخ وواقع وآفاق. Jadida, Morocco: مطبعة النجاح - الجديدة. ISBN 978-9981-59-129-5.

- "نموذج للخط الكوفي المرابطي بجامع القرويين". صوت القرويين | القلب النابض بمدينة فاس. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- "Qantara - The Almoravid dynasty (1056-1147)". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- معلمين، محمد. (2012). الخط المغربي الميسر. ISBN 978-9954-0-5214-3. OCLC 904285783.

- [email protected]. "أنواع الخطوط وأشكالها المختلفة". بيانات (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- "The Names of Allah ﷻ & Prophet Muhammad ﷺ (al-Qandusi) – Muhammadan Press". Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- Houdas, Octave, 1840-1916. (1891). Recueil de lettres arabes manuscrites. Adolphe Jourdan. OCLC 1025683823.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kane, Ousmane (2016-06-07). Beyond Timbuktu: An Intellectual History of Muslim West Africa. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05082-2.

- Krätli, Graziano; Lydon, Ghislaine (2011). The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18742-9.

- Al-Wazani, Hassan. "محمد بن الطيب الروداني قاض مغمور يُدخل بلاده عصر التنوير" [Muhammad ibn al-Tayyib al-Rudani: an obscure judge who brought his country into the age of enlightenment]. Al-Arab (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- "Folio from the "Blue Qur'an"". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- "Islamic art from museums around the world". Arab News. 2020-05-18. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- "Bifolium from the "Nurse's Qur'an" (Mushaf al-Hadina)". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- "Section from a Qur'an Manuscript". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- "A Manuscript of Five Sections of a Qur'an". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- "Bifolium from the Andalusian Pink Qur'an". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- O. Houdas, "Essai sur l'écriture maghrebine", in Nouveaux mélanges orientaux, IIe série vol. xix., Publications des Langues Vivantes Orientales (Paris 1886)

- N. van den Boogert, on the origin of Maghribi script

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maghrebi script. |