Senegambian stone circles

The Senegambian stone circles lie in The Gambia north of Janjanbureh and in central Senegal.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

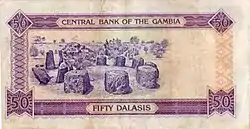

Wassu stone circles | |

| Location | The Gambia and Senegal |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (iii) |

| Reference | 1226 |

| Inscription | 2006 (30th session) |

| Area | 9.85 ha (24.3 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 110.05 ha (271.9 acres) |

| Coordinates | 13°41′28″N 15°31′21″W |

Location of Senegambian stone circles in The Gambia  Senegambian stone circles (Senegal) | |

With an approximate area of 30,000 km²,[1] they are sometimes divided into the Wassu (Gambian) and Sine-Saloum (Senegalese) circles, but this is purely a national division. According to UNESCO, the Senegambian stone circles are "the largest concentration of stone circles seen anywhere in the world."[2][3] "These sites, Wassu, and Kerbatch in Gambia, and Wanar and Sine Ngayene in Senegal, represent an extraordinary concentration of more than 1,000 stone circles and related tumuli spread over a territory of 100 km wide and 350 km in length, along the River Gambia.[4]

History

The stone circles and other megaliths found in Senegal and Gambia are sometimes divided into four large sites: Sine Ngayene and Wanar in Senegal, and Wassu and Kerbatch in the Central River Region in Gambia. Researchers are not certain when these monuments were built, but the generally accepted range is between the third century B.C. and the sixteenth century AD. Together the stone circles of laterite pillars and their associated burial mounds present a vast sacred landscape created over more than 1,500 years. It reflects a prosperous, highly organized and lasting society. Archaeologists have also found pottery sherds, human burials, and some grave goods and metals around the megalithic circles.[5] A small collection of these can be found in the British Museum's study collection that was donated by the colonial administrator Sir Richmond Palmer.[6] They include an iron bracelet and two spears.

Among these four main areas, there are approximately 29,000 stones, 17,000 monuments, and 2,000 individual sites. The monuments consist of what were originally upright blocks or pillars (some have collapsed), made of mostly laterite with smooth surfaces. The monoliths are found in circles, double circles, isolated or standing apart from circles (usually to the east) in rows or individually. These stones that are found standing apart outside the circles are called frontal stones. When there are frontal stones in two parallel, connected rows, they are called lyre-stones.[1]

The construction of the stone monuments shows evidence of a prosperous and organized society based on the amount of labor required to build such structures. The stones were extracted from laterite quarries using iron tools, although few of these quarries have been identified as directly linked to particular sites. After extracting the stone, identical pillars were made, either cylindrical or polygonal, with averages at two meters high and seven tons.[5] The builders of these megaliths are unknown. Possible candidates are the ancestors of the Jola people or the Wolof[7] but some believe that the Serer people are the builders. This hypothesis comes from the fact that the Serer still use funerary houses like those found at Wanar.[8]

World Heritage Sites

The Gambia:

- Stone circles of Kerr Batch 13.754565°N 15.068131°W

- Stone circles of Wassu 13.691525°N 14.873111°W

Senegal:

- Stone circles of Sine Ngayène 13.695278°N 15.535278°W

- Stone circles of Wanar 13.77429°N 15.52305°W

Wassu

Wassu is located in the Niani district of Gambia, and is made up of 11 stone circles their associated frontal stones. The tallest stone is found in this area, with a height of 2.59 meters. The builders of the monuments here possessed great knowledge of their local geology in order to find the sources of laterite stones. They must also have had great technical ability in order to extract these stones without splitting or cracking them.[9] The most recent excavations conducted on these megalithic circles date to the Anglo-Gambian campaign led by Evans and Ozanne in 1964 and 1965. The finds of burials enabled the dating of the monuments between 927 and 1305 AD.

Kerbatch

Kerbatch, an area comprising nine stone circles and one double circle,[5] The site possesses a ‘bifid’ stone, the only known one in the area and is located in Gambia's Nianija district. Kerbatch also features a V-shaped stone that had broken in three places and fallen.[10] This stone, that had been part of a frontal line, was restored during the 1965 Anglo-Gambian Stone Circles Expedition led by P. Ozanne. During this expedition Ozanne and his team excavated the double circle at Kerbatch.[11]

Wanar

The area of Wanar is located in the Kaffrine district of Senegal, and is made up of 21 stone circles and one double circle.[1] There are also numerous lyre-stones. In fact, one third of all Senegambian lyre-stones are located at Wanar.[12] All of the monuments found at Wanar seem to mark burials, according to the archaeologists working there. Researchers have also determined that the site was a burial ground first, and the stones were added later for ritual uses. Construction for this area can be narrowed down to between the seventh and fifteenth centuries A.D.[1]

A current dating program that has begun is yielding estimates that date the construction of the double circle to between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.[13] A 2008 excavation was conducted on the double circle at Wanar, and two types of burials were distinguished:[1] simple burials that consisted of large pits sealed with a mound, and more complex burials that were deep with narrow mouths. There was also a presence of perishable materials found in the burials, such as brick and plaster, that suggests the existence of funerary houses built at the time of burial.[14]

Two types of stones were found at Wanar: tall and slender stones that tended to be cylindric; and shorter, squatter, trapezoidal shaped stones as well.[8] There is a trend found in which frontal lines do not match up with their corresponding circles, which may suggest a chronological order that the monuments were constructed.

There are many other clues to be found at Wanar that can tell about what these monuments originally looked like. For instance, the inner ring of the double circle features fallen monoliths that all fan out from the center of the monument. This may suggest, coupled with findings of drystone around the monument, that there used to be drystone beneath the monoliths, and the cylinder made up of the inner ring and drystone was once filled with earth, so that when it collapsed due to outward pressure, the stones all fell outward as well. This theory is not refuted by the fact that the stones of the outer ring fell in all different directions, lacking outward pressure.[15]

Pottery shards were also found scattered around the site, buried in different layers of earth. The certain layers in which the pottery was found says that some deposition occurred after the fall of the drystone, but before the collapse of the monoliths. In other words, pottery may have been deposited at this monument after total and/or partial abandonment of the monoliths. Overall, the destruction of this double circle was a slow disintegration over time, as opposed to one large and sudden collapse.[12]

Based on all of these findings, researchers have developed a possible model for the funeral activity sequence that took place at Wanar. The sequence has three distinct phases: Phase one includes cutting the graves in the subsoil with funerary rites, such as covering the graves with mounds; phase two is when the standing stones were raised around the mounds; phase three consisted of erecting frontal stones. Phase three may also have been when these monuments became sites of ritual activities and ceramics started getting deposited around them. The creators of this model recognize that other sequences are possible, and the order for the sequence of events at the double circle may have been different as well.[16]

Sine Ngayene

Sine Ngayene is the largest of the four areas, and home of 52 stone circles, one double circle, and 1102 carved stones. It is generally accepted that the single burials found here predate the multiple burials that are associated with the construction of the stone circles.[5] The site of Sine Ngayene is located just northwest of Sine, Senegal, at the coordinates of 15°32′W, 13°41′N.[17]

In 2002, an expedition was launched in the Petit-Bao-Bolong drainage tributary; it was called Sine-Ngayene Archaeological Project (SNAP). The team found iron smelting sites and quarries located close to the monument sites.[11] They also found evidence of hundreds of homes nearby, dating around the time of the monuments, clustered in groups of 2–5 with remnants of house floors and pottery shards. This evidence suggests the existence of small, linked yet independent communities. Researchers also suggest the possibility that these megalithic cemeteries could have been a focal spot of the cultural landscape and served the purpose of bringing people together.[17]

The site of Sine Ngayene has a Y-shaped central axis with a double circle (called Diallombere) located at the center of the three branches. Originally this site was surrounded by hundreds of tumuli (burial mounds) that leveled over time through erosion.[18] Evidence suggests that the burials occurred first with the stones being erected later, exclusively for the burials. Often frontal stones were erected on the East side of the stone circles.[11] Archaeologists at Sine Ngayene have constructed a timeline with four distinct, successive cycles. These cycles are based on materials buried in successive layers and the monument construction chronology of the double circle at the center of the site. The approximate date range assigned to this timeline ranges from 700 A.D. to 1350 A.D.[19]

Cycle One

Materials for the first cycle are located at approximately 1.6-2.0 meters below the surface and are dated between 700 and 800 A.D. The main finding for this cycle was a large, oblong-shaped pit with a concentration of human remains in the form of a secondary burial. The remains were found with five iron spearheads and a copper bracelet. The pit was backfilled and capped with a mound overlaid with scattered laterite blocks. Researchers estimate that the outer circle of stones was built after the initial burial, and two large frontal stones were added.[20]

Cycle Two

The layers analyzed for the second cycle are located at approximately 1.0-1.6 meters below the surface and date between 800 and 900 A.D. For this layer, another oblong-shaped burial pit was discovered.[21] However, this burial area consisted of more selective human bones, mostly long bones, and skulls, buried in discrete episodes. These were also linked to secondary burials. Overall there were ten skulls, thirty long bones, and one iron spearhead found.[22]

Cycle Three

Cycle three encompassed material between 0.5 and 1.0 meter below the surface, and dates to between 900 and 1000 A.D. This time period is when the inner circle of monoliths is speculated to have been built. Within this layer, a laterite slab was also discovered, which may have been used as a sacrificial table.[22] The majority of the findings, however, consisted of clay sherds, selected bones (long bones and skulls), and human teeth deposited with pottery.[23] It is during this time in which the monument evolved from a selective burial ground, to a broader ritual place, becoming more of a "public monument". There was a shift from burials to offerings during this cycle.[24]

Cycle Four

This cycle contains material located from the surface to approximately 0.5 meters below the surface, and is dated from anywhere between 1235 and 1427 A.D. During this period there seems to be a low intensity use of the monument, and some things recovered from this layer may be accidental re-depositions.[24] The majority of findings from this zone were small bone fragments buried with laterite blocks, located primarily in the inner circle of the monument. There were also some sherds found in one spot, and a secondary burial pit containing: 70 bones, seven turquoise beads, and two copper rings. This may suggest long-distance trade among the people who used the monuments. Overall, cycle four contained a mixture of offerings and secondary burials.[25]

Additional stone circles in Senegambia

- Stone circles of Dialla Kouna

- Stone circles of Farafenni

- Stone circles of Garan

- Stone circles of Kabakoto

- Stone circles of Kau-ur

- Stone circles of Kaymor

- Stone circles of Kerr Jabel

- Stone circles of Keur Bakary

- Stone circles of Keur Bamba

- Stone circles of Keur Katim Diama

- Stone circles of Kuntaur Fulla Kunda

- Stone circles of Lamin Koto'

- Stone circles of Médina Sabak

- Stone circles of Niani Maru

- Stone circles of Nioro Kunda

- Stone circles of N'jai Kunda

- Stone circles of Palan Mandika

- Stone circles of Payoma

- Stone circles of Windé Walo

Notes

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 410

- UNESCO, Stone Circles of Senegambia [in] Alvarez, Melissa, Earth Frequency: Sacred Sites, Vortexes, Earth Chakras, and Other Transformational Places, pp. 152-3, Llewellyn Worldwide (2019), ISBN 9780738755410 (Retrieved 8 July 2019)

- World Heritage Site, Stone Circles of Senegambia (Retrieved 8 July 2019)

- UNESCO, Stone Circles of Senegambia (Retrieved 8 July 2019)

- whc.unesco.org/en/list/1226 "Stone Circles of Senegambia 2006

- British Museum Collection

- Hughes, Arnold; Perfect, David (2008). Historical Dictionary of The Gambia. Scarecrow Press. p. 224-225. ISBN 978-0-8108-6260-9. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 415

- allafrcia.com/stories/201206200701.html Yunus Saliu, "Gambia: World Heritage Sites of the Gambia- Wassu and Kerbatch Stone Circles", allAfrica 6/20/2012

- allafrica.com/stories/201206200701.html Yunus Saliu, "Gambia: World Heritage Sites of the Gambia- Wassu and Kerbatch Stone Circles", allAfrica 6/20/2012

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 130

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 418

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 421

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 411

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 417

- Laport et al. 2012, p. 421

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 131

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 128

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 127)

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 136

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 138

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 140

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 143

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 144

- Holl et al. 2007, p. 146

External links

- The Senegambian Megaliths Project, http://www.mae.u-paris10.fr/prehistoire/IMG/pdf/Senegambian_Megaliths_Project.pdf

- The Wassu Stone Circles on Google Street View, https://goo.gl/maps/BTQj37cY2UgHBKcv7 (Published: October 2019)

References

- "Stone Circles of Senegambia", 2006. UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- Yunus Saliu. "Gambia: World Heritage Sites of the Gambia- Wassu and Kerbatch Stone Circles", 6/20/2012. allAfrica

- Holl, A. F., Bocoum, H., Deuppen, S., and Gallagher, D. (2007). Switching mortuary codes and ritual programs: The double-monolith-circle from Sine-Ngayene, Senegal. Journal of African Archaeology, 5(1), 127–148.

- Laport, L., Bocoum, H., Cros, J. P., Delvoye, A., Bernard, R., Diallo, M., Diop, M., Kane, A., Dartois, V., Lejay, M., Bertin, F., and Quensel, L. (2012). Megalithic monumentality in Africa: from graves to stone circles at Wanar, Senegal. Antiquity, 86(332), 409–427.