Hachijō language

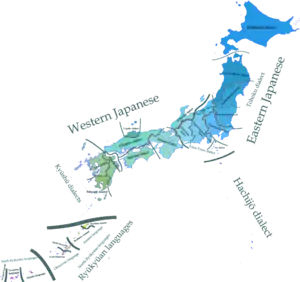

The small group of Hachijō dialects are the most divergent form of Japanese or form a fourth branch of Japonic (alongside Japanese, Northern Ryukyuan, and Southern Ryukyuan).[4] Hachijō is currently spoken on two of the Izu Islands south of Tokyo—Hachijō-jima and the smaller Aogashima—as well as on the Daitō Islands of Okinawa Prefecture, which were settled from Hachijō-jima in the Meiji period. It was also previously spoken on the island of Hachijō-kojima, which is now abandoned. Based on the criterion of mutual intelligibility, Hachijō may be considered a distinct Japonic language.

| Hachijō | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Japan |

| Region | Southern Izu Islands and the Daitō Islands |

Native speakers | < 1000 (2011)[1][2] |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | hhjm |

| Glottolog | hach1239 |

| ELP | Hachijo[3] |

Hachijō dialects retain ancient Eastern Old Japanese grammatical features as recorded in the 8th-century Man'yōshū. There are also lexical similarities with the dialects of Kyushu and even the Ryukyuan languages; it is not clear if these indicate the southern Izu islands were settled from that region, if they are loans brought by sailors traveling among the southern islands, or if they might be independent retentions of Old Japanese.[5]

Hachijō is a moribund language with a small and dwindling population of primarily elderly speakers.[6] However, since at least 2009, the town of Hachijō has supported efforts to educate its younger generations about the language through primary school classes, karuta games, and Hachijō-language theater productions.[7]

Classification and dialects

The dialects of Hachijō are classified into eight groups according to the various villages within Hachijō Subprefecture. On Hachijō-jima, these are Ōkagō, Mitsune, Nakanogō, Kashitate, and Sueyoshi; on Hachijō-kojima, these were Utsuki and Toriuchi; and the village of Aogashima is its own group. The Daitō Islands presumably have their own dialect(s) as well, but these are not well-described. The dialects of Ōkagō and Mitsune are very similar, as are those of Nakanogō and Kashitate. The Hachijō language and its dialects are classified by John Kupchik[8] and the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL),[9] respectively, within the Japonic family as follows:

- Japonic languages

- Japanesic languages

- Eastern Old Japanese

- Hachijō language

- Ōkagō & Mitsune dialects

- Nakanogō & Kashitate dialects

- Sueyoshi dialect

- Hachijō language

- Western-Central Old Japanese

- Eastern Old Japanese

- Ryukyuan languages

- Japanesic languages

(The other dialects were not subclassified within Hachijō by NINJAL.)

The dialects of Aogashima and Utsuki are quite distinct from the other varieties (and each other). The Aogashima dialect exhibits slight grammatical differences from other varieties, as well as noticeable lexical differences. The Utsuki dialect, on the other hand, is lexically similar to the Toriuchi dialect and those of Hachijō-jima, but has undergone several unique sound shifts such as the elimination of /ɾ/ and /s/.[10][11]

The dialects of Hachijō-jima are, like its villages, often referred as being "Uphill" (上坂) or "Downhill" (下坂). The villages of Ōkagō and Mitsune in the northwest are "Downhill," while the villages of Nakanogō, Kashitate, and Sueyoshi in the south are "Uphill"—though the Sueyoshi dialect is not particularly close to the other "Uphill" dialects.[12]

As the number of remaining speakers of Hachijō as a whole is unknown, the numbers of remaining speakers of each dialect are also unknown. Since the abandonment of Hachijō-kojima in 1969, some speakers of the Utsuki and Toriuchi dialects have moved to Hachijō-jima and continue to speak the Hachijō language, though their speech seems to have converged with that of the "Downhill" dialects.[12] As late as 2009, the Toriuchi dialect had at least one remaining speaker, while the Utsuki dialect had at least five.[13]

Phonology

Like Standard Japanese, Hachijō syllables are (C)(j)V(C), that is, with an optional syllable onset, optional medial glide /j/, and an optional coda /N/ or /Q/. The coda /Q/ can only be present word-medially, and the syllable nucleus V can be a short vowel, a long vowel, or a diphthong.

The medial glide /j/ represents palatalization of the consonant it follows, which for certain consonants also involves a change in place or manner of articulation. Like in Japanese, these changes can also be analyzed phonemically using separate sets of palatalized and non-palatalized consonants.[14] However, from a morphological and cross-dialectal perspective, it is more straightforward to treat palatalized consonants as sequences of consonants and /j/, as is done in this article—following the phonemic analysis made by Kaneda (2001).[15] Furthermore, when a vowel or diphthong begins with the close front vowel /i/ (but not near-close /ɪ/), the preceding consonant (if any) becomes palatalized just as if the medial /j/ were present.

Hachijō can be written in Japanese kana or in romanized form. The romanized orthography used in this article is based on that of Kaneda (2001),[15] but with the long vowel marker ⟨ː⟩ replaced by vowel-doubling for ease of reading.

Vowels

There are five short vowels found in all varieties of Hachijō:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Hachijō long vowels and diphthongs vary in quality based on the specific dialect. However, there are relatively straightforward correspondences between the dialects:[16][17]

| This Article | ii | uu | aa | ee | ei | oo | ou |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kashitate | ii | uu | aa | ia~jaa[lower-alpha 1] | ɪɪ~ee | oɐ | ʊʊ~oo |

| Nakanogō | ii | uu | aa | ea~jaa[lower-alpha 2] | ee | oɐ | oo |

| Sueyoshi | ii | uu | aa | ee | ii | aa | oo |

| Mitsune | ii | uu | aa | ee~ei[lower-alpha 3] | ei | oo~ou[lower-alpha 3] | ou |

| Ōkagō | ii | uu | aa | ee | ee | oo | oo |

| Toriuchi | ii | uu | aa | ee | ee | oo | oo |

| Utsuki | ii | uu | aa | ee | ɐi | oo | ɐu |

| Aogashima | ii | uu | aa | ee | ei~ee | oo | ɔu |

- Causes palatalization due to initial /i/~/j/.[18]

- Varies depending on the time period, lexeme, and speaker. When found as jaa, it causes palatalization, but when found as ea, it does not.[19]

- Descriptions of the Mitsune dialect differ in opinion as to whether speakers distinguish /ee/ and /oo/ from /ei/ and /ou/. Kaneda (2001) claims that they do, separating them in his transcription, while NINJAL (1950) lists only /ei/ and /ou/ for the Mitsune dialect.[20][17]

Consonants

Hachijō contains roughly the same consonants as Standard Japanese, with most consonants able to be followed by all vowels as well as by the medial glide /j/.[15]

| Bilabial | Coronal[lower-alpha 1] | Velar | Laryngeal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m m | n n | ||||

| Plosive / Affricate |

Voiceless | p p | t t[lower-alpha 2] | c t͡s | k k | |

| Voiced | b b[lower-alpha 3] | d d[lower-alpha 2] | z d͡z | g ɡ | ||

| Fricative | s s[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] | h h[lower-alpha 6][lower-alpha 7] | ||||

| Tap | r ɾ[lower-alpha 8] | |||||

| Approximant | w w | j j[lower-alpha 9] | ||||

| Special morae | N /N/,[lower-alpha 10] q /Q/[lower-alpha 11] | |||||

- When palatalized, the coronal consonants n, t, d, c, z, and s change from an alveolar place of articulation to a palatal one, and the plosives become sibilant affricates. This latter change is also reflected in Kaneda's orthography, with the replacement of tj and dj with cj [t͡ɕ] and zj [d͡ʑ], etc.[21][15]

- When followed by the close back vowel u /u/, t /t/ and d /d/ become affricated, merging into cu /t͡su/ and zu /d͡zu/.[22][15]

- In the Utsuki dialect, intervocalic b /b/ is realized as a bilabial fricative [β].[23]

- The phoneme s /s/ has been lost in the Utsuki dialect, having merged into c /t͡s/.[24][25]

- When s /s/ is preceded by the geminating consonant q, an excrescent [t] causes it to become affricated [t͡s], thus merging it into qc [tt͡s].[26]

- When h /h/ is followed by the close back vowel /u/, it is realized as bilabial [ɸ], whereas when palatalized, it is realized as palatal [ç].[27]

- The phoneme h alternates morphophonemically with p /p/ when preceded by the geminating phoneme q, e.g., oq- (intensifying prefix) + hesowa "to push" → oqpesowa "to push."[28]

- The phoneme r /ɾ/ has been lost in the Utsuki dialect, having merged into j /j/ or a zero consonant depending on the phonemic environment.[29]

- As mentioned above, palatalized consonants are analyzed as clusters of a consonant plus /j/ as a medial glide. When serving as a syllable onset, /j/ cannot be palatalized (as it is already palatal), reducing any would-be sequences of **/jj/ to simply /j/.[15]

- The phoneme N can only be found in the syllable coda and corresponds to the syllable onsets m and n. Its default realization is dorsal [ŋ], but if it is immediately followed by an obstruent or nasal consonant in the same word, then it assimilates to the place of articulation of that consonant.[30]

- The phoneme q /Q/ represents gemination of the following consonant, just as the character っ does in Japanese hiragana. Unlike in Standard Japanese, however, q can be found preceding not only voiceless obstruents, but voiced ones as well.[31]

Like all Japonic languages, Hachijō exhibits the morphophonemic alternation known as rendaku, where word-initial voiceless obstruents alternate with voiced ones in some compounds. Specifically, rendaku is exhibited through the following alternations in Hachijō:

| Without Rendaku | p | h | t | c | s | k |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Rendaku | b | d | z | g | ||

Grammar

Hachijō preserves several features from Old Japanese—particularly Eastern Old Japanese—that have been lost in Modern Standard Japanese, for example:[32][33]

- Verbal adjectives have the attributive ending -ke. (Contrast Western Old Japanese -ki1, Modern Japanese -i.)

- Verbs distinguish the conclusive (終止形 shūshikei) ending -u from the attributive (連体形 rentaikei) ending -o.

- The Eastern Old Japanese progressive inflection -ar- has become a suffix -ar- roughly indicating the past tense in Modern Hachijō. (Contrast Western Old Japanese -e1r-.)

- The inferential mood is marked by -unou, a descendant of the verbal auxiliary -unamu seen in Eastern Old Japanese. (Contrast Western Old Japanese -uramu.)

- The existence verb aru is used with all subjects, without the animate–inanimate (iru–aru) distinction made on the mainland.

- The particles ga and no can both be used productively to mark the subjects of a sentences as well as the genitive case.

- The word for "what" is ani, as in Eastern Old Japanese. (Contrast Western Old Japanese and Modern Japanese 何 nani)

Nominals and demonstratives

Nominals in Hachijō function largely the same as their counterparts in Japanese, where they can be followed a variety of case-marking postpositions to indicate semantic function. However, some former postpositions have phonemically contracted with nominals that they mark, depending on the nominals' endings:[34]

| Bare Form | With -o (を) | With -i (へ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a-final | ...a | ...oo | ...ee |

| i-final | ...i | ...jo | ...ii |

| u-final | ...u | ...uu | ...ii |

| e-final | ...e | ...ei | ...ei |

| o-final | ...o | ...ou | ...ei |

| long vowel-final / diphthong-final |

...VV | ...VVjo | ...VVjii[lower-alpha 1] |

| N-final / diphthong-final |

...N | ...Njo | ...Njii[lower-alpha 1] |

- The phoneme /j/ disappears phonetically before /i/, but it is included here to clearly separate syllables in transcription. Furthermore, in the Aogashima dialect, these cases of jii instead become rii.

In some older texts, the topic-marking particle wa (corresponding to Japanese は wa) can also be seen contracting with words it follows, but such contractions with wa have fallen out of use in the present day. Furthermore, the particle N ~ ni (corresponding to Japanese に ni) has different forms depending on the word it follows; a general guideline is that if the word ends with a short vowel sound, it uses the form N, whereas words ending in long vowels, diphthongs, or /N/ use ni.[35]

The pronominal system of Hachijō has been partly inherited from Old Japanese and partly borrowed from Modern Japanese:[36]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Person | ware[lower-alpha 1] | warera |

| are[lower-alpha 1] | arera | |

| 2nd Person | nare[lower-alpha 1] | narera |

| omi, omee, omai | omira, omeera, omaira | |

| unu | unura, una | |

| Interrogative: "who" | dare[lower-alpha 1] | darera |

| Interrogative: "what" | ani | |

- Pronouns ending in -re can often contract it to -i, which does not monophthongize with the preceding vowel; e.g., ware > wai.

A series of demonstratives similar to Modern Japanese's ko-so-a-do series (proximal-mesial-distal-interrogative) also exists in Hachijō:[37]

| Proximal (ko-) | Mesial (so-) | Distal (u-) | Interrogative (do-) | Japanese Equivalent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal (sg.) -re "this, that" |

kore[lower-alpha 1] | sore[lower-alpha 1] | ure[lower-alpha 1] | dore[lower-alpha 1] | ~れ |

| Nominal (pl.) -rera "these, those" |

korera | sorera | urera | dorera | ~れら |

| Person -icu "this person, that person" |

koicu | soicu | uicu | doicu | ~いつ |

| Determiner -no "this ~, that ~" |

kono | sono | uno | dono | ~の |

| Location -ko "here, there" |

koko | sono | uko | doko | ~こ |

| Direction -qci/-cira/-qcja "hither, thither" |

koqci, kocira, koqcja | soqci, socira, soqcja | uqci, ucira, uqcja | doqci, docira, doqcja | ~っち、~ちら |

| Manner, Extent -gooni[lower-alpha 2] "in this way, in that way" |

kogooni, kogoN | sogooni, sogoN | ugooni, ugoN | dogooni, dogoN adaN[lower-alpha 3] |

~う、~んなに |

| Type -goN doo[lower-alpha 4] "this kind of, that kind of" |

kogoN doo | sogoN doo | ugoN doo | dogoN doo adaN doo[lower-alpha 3] |

~んな |

- Just as with personal pronouns, these final -re can often contract it to -i, which does not monophthongize with the preceding vowel; e.g., kore > koi.

- The ending -gooni is often shortened to having a short vowel and/or having N for ni, which is represented here as -goN. However, the exact form depends on the dialect. For instance, it is -/gaN/ in the Sueyoshi dialect and -/goɐN/ in the Kashitate dialect.

- There are subtle differences between dogooni/dogoN and adaN. For instance, when wondering to oneself, only adaN is appropriate, e.g., adaN sjodoo "What ever shall I do?"[38]

- This morpheme doo is the attributive form of the copular verb dar- "to be."

Verbals

Like other Japonic languages, Hachijō's verbs and verbal adjectives can be analyzed as combinations of a handful of stem forms followed by a wide variety of suffixes. The main stem forms are:[39]

- "Irrealis" form (未然形 mizenkei) -a

- Not a true stem, but rather a paradigmatically regular way in which many affixes beginning with -a- are added to verbs.

- Infinitive form (連用形 ren'yōkei) -i

- Used in a linking role (a kind of serial verb construction), as well as for nominalizing verbs.

- Conclusive form (終止形 shūshikei) -u

- Can be used as a predicative form, but usually restricted to inferential and quotative subordinate clauses. Its function in main clauses has been supplanted by -owa, a combination of the attributive form -o and the declarative-marking particle -wa.

- Attributive form (連体形 rentaikei) -o

- Used to define or classify nominals, similar to a relative clause in English; when linked in this way to a null noun, it can also be used to nominalize verbs. In addition, ordinary declarative sentences are made by adding one of the particles -wa or -zja to the end of attributive forms.

- Evidential form (已然形 izenkei) -e

- Used in the formation of certain non-finite subordinate clauses. Also found in main clauses when the rule of kakari-musubi is invoked by the focusing particle ka ~ koo (just as in Classical Japanese with the particle こそ koso).

- Imperative form (命令形 meireikei) -e/-ro

- Used to form commands.

- te-Form (中止形 chūshikei) -te

- Used to form coordinating clauses and certain serial verb constructions.

- Progressive form (アリ形 ari-kei) -ar-

- Descends from the Old Japanese progressive aspect, but has changed in meaning closer to a past tense in modern Hachijō. On some verbs, the progressive suffix is added twice with little or no difference in meaning.

- Bare Stem

- The "true" stem of a verb, from which all of the above stems can be derived. For type-1 verbs, it ends in a consonant, while for type-2 verbs, it ends in a vowel i or e.

In wordlists, verbs are usually cited their plain declarative form, which is the attributive plus the particle -wa, e.g., kamowa "to eat" (bare stem kam-).

Based on these stem forms, one can identify nine regular verb paradigms, two irregular verb paradigms, one verbal adjective paradigm, and the highly irregular negative paradigm. In the following table, examples are given for each conjugation type; the numbering of the conjugations is from Kaneda (2001).[40] This table cannot exhaustively predict all inflected forms, especially for irregular verbals, but can serve as a general guideline.

| Conjugation Type | "Irrealis" | Infinitive | Conclusive | Attributive | Evidential | Imperative | te-Form | Progressive Stem | Bare Stem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1A[lower-alpha 1] | Strong Consonant, te-form -qte kak- "to write" |

kaka- | kaki | kaku | kako | kake | kake | kaqte | kakar- | kak- |

| 1.1A' | Weak Consonant, te-form -qte uta(w)- "to sing" |

utawa-, utoo- | utee | utou | utou | utee | utee | utaqte | utoorar-[lower-alpha 2] | utaw- |

| 1.1B | Strong Consonant, te-form -te kook- "to dry" |

kooka- | kooki | kooku | kooko | kooke | kooke | koote | kookar- | kook- |

| 1.2A | Strong Consonant, te-form -Nde nom- "to drink" |

noma- | nomi | nomu | nomo | nome | nome | noNde | nomar- | nom- |

| 1.2B | Strong Consonant, te-form -de eem- "to walk" |

eema- | eemi | eemu | eemo | eeme | eeme | eede | eemar- | eem- |

| 1.3A[lower-alpha 3] | Weak-s, Euphonic hu(s)- "to bow" |

husa- | hii | husu | huso | huse | huse | hiite | hiitar-[lower-alpha 4] | hus- |

| 1.3A'[lower-alpha 3] | Weak-s, Non-Euphonic tou(s)- "to send" |

tousa- | touii | tousu | touso | touse | touse | touiite | touiitar-[lower-alpha 4] | tous- |

| 1.3B | Strong-s hes- "to push" |

hesa- | hesi | hesu | heso | hese | hese | hesite | hesitar-[lower-alpha 4] | hes- |

| 2 | Vowel Verbs ki- "to wear" |

ki- | ki | ki(ru) | kiro | kire | kiro | kite | kitar-[lower-alpha 4] | ki- |

| 3 | Irregular: k(o)- "to come" | ko- | ki | ku(ru) | kuro | kure | ko | kite | kitar-[lower-alpha 4] | k- |

| Irregular: s(j)- "to do" | sa-, sja- | si | su | sjo | sje | sje | site | sitar-[lower-alpha 4] | sj- | |

| VA | Verbal Adjective bou- "large" |

bou-ka- | bou-ku | (bou-ke)[lower-alpha 5] | bou-ke[lower-alpha 6] | bou-ke | –[lower-alpha 7] | bou-kute | –[lower-alpha 7] | bou- |

| Neg. | Negative -Nna(k)- "doesn't ..." |

-Nna(ka)(r)a- | -zu | -Nnoo | -Nnoo[lower-alpha 8] | -Nnare | –[lower-alpha 9] | (-Nnaqte)[lower-alpha 10] | -Nna(ka)r- | -Nna(k)- |

- While otherwise following the 1.1A paradigm, the progressive suffix -ar- and the copula dar- have a couple of irregular contracted forms, such as their attributive *...aro becoming ...oo, and their declarative *...arowa becoming ...ara.

- The progressive -ar- is usually added twice to type-1.1A' verbs (with no change in meaning) as shown here because the first -ar- merges phonemically with the root.

- For many speakers, verbs that once followed these conjugations are now conjugated as type 1.3B instead.

- The t of these forms descends from the te-form: -te ar- > -tar-.

- The otherwise attributive ending -ke can be used as a conclusive form in very specific cases, such as when followed by the particle to in the sense of "if."

- The ending -ke contracts with the declarative ending -wa to make -kja.

- Where verbal adjectives are defective, they are supplemented by inflections of -kar- (a contraction of -ku ar-), which conjugates as a special 1.1A verb just like the copula dar-.

- From older *-Nnako, and when combined with the declarative -wa, this instead becomes -Nnaka.

- The negative imperative is expressed by the prohibitive suffix -una instead.

- Not used directly, but this is the underlying form used in forms derived from the te-form.

Non-verbal adjectives such as heta "unskilled, crude" are used with the copula dar- in order to describe nouns, e.g., heta doo sito "unskilled person."

In addition to the basic forms listed above, a number of affixes can be added to verb stems to further specify their semantic and/or syntactical function. Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of affixes that can be found in independent clauses:

- Inferential (推量 suiryō) = conclusive + -na(w)-

- Further conjugated as a type-1.1A' verb. Indicates that the speaker is guessing or supposing that the statement is true. Almost always seen in its attributive form -nou.

- si-Desiderative (si願望 si ganbou) = attributive + -osi

- Does not inflect further. Indicates a wish, need, or obligation on the part of the subject. Etymologically from the attributive + Old Japanese 欲し posi "wanting."

- sunou-Desiderative (sunou願望 sunou ganbou) = attributive + -osunou

- Does not inflect further. Indicates a wish, need, or obligation on the part of the subject, but implies that achievement of it is out of reach or otherwise distant or difficult. Etymologically from the attributive + Old Japanese 欲すなむ posunamu "wanting (tentative mood)."

- Negative (否定 hitei) = infinitive + Nnaka

- Conjugated according to the Negative inflection. Makes a verb express a negative meaning, like English "does not ~." Mostly originates from the Old Japanese phrasing ~に無く在る ni naku ar- > *Nnakar-, with different contractions in each derived and inflected form.

- Counterfactual (反語 hango) = "irrealis" + -roosi

- Does not inflect further. With a first-person subject, indicates an unwillingness or inability to perform an action; with a second- or third-person subject, indicates belief that the supposed action (past, present, or future) cannot or must not be true. Etymology unclear.

- Past Tense (過去 kako) = te-form, but replacing te/de with ci/zi

- Now uncommon, this was the original past tense in Hachijō before it was supplanted in function by the progressive suffix -ar-. It descends from Old Japanese ~し -si, the attributive form of the past tense auxiliary ~き ki1.

- wa-Declarative (wa形断定 wa-kei dentei) = attributive + -wa

- Marks the verb as an ordinary predicate. Contracts with the progressive suffix's -ar-o to make -ara, and with the adjectival attributive -ke to make -kja. It descends from the topic marker は. Has supplanted the original conclusive form -u for most purposes.

- zja-Declarative (zja形断定 zja-kei dentei) = attributive + -zja

- Marks the verb as an ordinary predicate, but provides additional emphasis similarly to Standard Japanese よ yo or ね ne. Also serves as a tag question when used with interrogative sentences, similarly to Standard Japanese でしょう deshou. A contraction from Old Japanese にては nite pa or のでは no de pa > *dewa > *dya > zja.

- Prohibitive (禁止 kinshi) = conclusive + -na

- The negative equivalent of the imperative form. Commands the listener to not do something. Inherited from Old Japanese.

- Mirative (感嘆 kantan) = attributive + -u

- Used for expressing amazement or surprise. For type-1.1A' verbs, formed instead by taking the bare stem and adding -ou, e.g., uta(w)- "to sing" > utawou. Verbal adjectives instead replace the attributive -ke with -soo. Etymologically from the attributive + the Old Japanese object-marking and mirative particle を wo, or in the case of verbal adjectives, from the nominalizing suffix ~さ -sa followed by を wo.

- Volitional (意志 ishi) = attributive + -u

- Indicates a personal willingness or suggestion to perform the action. For type-1.1A' verbs, formed instead by taking the bare stem and adding -ou, e.g., uta(w)- "to sing" > utawou. Can also be used for offering suggestions, recommendations, or encouragement, in which cases it is sometimes followed by -bei or -zja.

- Hortative (勧誘 kan'yū) = attributive + -gooN

- Used for offering suggestions, recommendations, or encouragement. Often shortened to just -goN (or -gaN in the Sueyoshi dialect).

- Requisitional (依頼 irai) = te-form, but final -e > -ou

- A mild imperative used for asking favors from others. Means roughly "Please ~," or "Could you ~."

In addition, the following affixes are only found in dependent clauses that are linked to a main clause:

- Concessive (逆接 gyakusetsu) = evidential + -dou

- Introduces adverse information despite which the main clause still nevertheless occurs/occurred; roughly translatable as "Although ~." From Old Japanese -e2-do2mo2 > *-edowo > -edou.

- Conjunctive (順接 junsetsu) = evidential, but final e > -ja

- Introduces an event that is causally or temporally related to the main clause; roughly translatable as "Because ~," or "When ~." From Old Japanese -e2-ba > *-ewa > -ja.

- Conditional (条件 jouken) = "irrealis" + -ba

- Introduces a condition or prerequisite that, if met, results/resulted in the main clause; roughly translatable as "If ~," or "When ~." From Old Japanese -aba.

- Purposeful (目的 mokuteki) = infinitive + (n)i

- Indicates an objective for whose purpose the main clause occurs/occurred, just as its Japanese counterpart of infinitive + ~に ni, roughly translatable as "In order to ~."

Vocabulary

Hachijō preserves a number of phrases that have been otherwise lost in the rest of Japan, such as magurerowa for standard 気絶する kizetsu suru 'to faint, pass out'. Hachijō also has unique words that are attested nowhere else, such as togirowa "to invite, to call out to" and madara "one's nicest clothes." Finally, there are words which do occur in standard Japanese, but with different meanings or slightly different pronunciation:[41][42]

| Hachijo | Meaning | Japanese Cognate | Japanese Equivalent in Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| jama | field | 山 yama "mountain" | 畑 hatake |

| kowa-ke | tired, exhausted | 怖い kowai "scary, scared" | 疲れる tsukareru "to be tired" |

| gomi | firewood | ゴミ gomi "trash" | 薪 takigi |

| niku-ke | ugly | 憎い nikui "detestable, difficult" | 醜い minikui |

| kamowa | to eat | 噛む kamu "to chew, to bite" | 食べる taberu |

| oyako | relatives, kin | 親子 oyako "parent and child" | 親戚 shinseki |

| izimerowa | to scold, to reprove | 苛める ijimeru "to tease, to bully" | 叱る shikaru |

| heirowa | to shout, to cry out | 吠える hoeru "(of a dog) to bark, to howl" | 叫ぶ sakebu |

| sjo-ke | known | 著き siru-ki1 ~ (iti)siro1-ki1 "known, evident" (OJ) | 知る shiru "to know" |

| jadorowa | to sleep | 宿る yadoru "to stay the night" | 眠る nemuru, 寝る neru |

| marubowa | to die | 転ぶ marobu "to collapse, to fall down" | 死ぬ shinu, 亡くなる nakunaru |

| heqcogo | navel | 臍 heso "navel" + 子 ko "(diminutive)" | 臍 heso |

References

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 3–14.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 13–14.

- Endangered Languages Project data for Hachijo.

- Thomas Pellard. The comparative study of the Japonic languages. Approaches to endangered languages in Japan and Northeast Asia: Description, documentation and revitalization, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, Aug 2018, Tachikawa, Japan. ffhal-01856152

- Masayoshi Shibatani, 1990. The Languages of Japan, p. 207.

- Vovin (2017).

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 14–15.

- Kupchik (2011), p. 7.

- NINJAL (1950), pp. 162–166.

- Kaneda (2001), p. 39.

- NINJAL (1950), pp. 191–201.

- Iannucci (2019), p. 95–96.

- 山田平右エ門 (Yamada Heiuemon), 2010. 消えていく島言葉~八丈語の継承と存続を願って~ (A Disappearing Island Language ~Wishing for the Inheritance and Survival of the Hachijo Language~), pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-4-87302-477-6

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 63–66.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 15–16.

- Kaneda (2001), p. 28.

- NINJAL (1950), pp. 129–134, 191–201.

- Iannucci (2019), p. 100.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 100, 149–151.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 27–28.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 44–50, 52-61.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 52–61.

- NINJAL (1950), p. 196.

- NINJAL (1950), p. 195.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 59.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 59–63.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 41–42.

- Iannucci (2019), p. 39.

- NINJAL (1950), pp. 192–194.

- Iannucci (2019), p. 62.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 62–63.

- Kupchik (2011).

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 3–14, 35–38, 109–120.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 39, 47.

- Kaneda (2001), p. 44.

- Kaneda (2001), p. 70.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 72–73.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 77.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 109–130.

- Kaneda (2001), pp. 147–158.

- "八丈島の方言" [The Hachijō-jima dialect]. Ōwaki izakaya. 居酒屋おおわき. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- Iannucci (2019), pp. 147–269.

Works cited

- Vovin, Alexander (2017), "Origins of the Japanese Language", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.277.

- Iannucci, David J. (2019), The Hachijo Language of Japan: Phonology and Historical Development, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Ph.D. Thesis.

- Kupchik, John E. (2011), A Grammar of the Eastern Old Japanese Dialects, University of Hawaiʻi. Ph.D. Thesis.

- Kaneda, Akihiro (2001), 八丈方言動詞の基礎研究 (Basic Research on Verbs in the Hachijo Dialect), 笠間書院 (Kasama Shoin Co., Ltd.).

- NINJAL (1950), 八丈島の言語調査 (Language Survey of Hachijo-jima).

Further reading

- (in Japanese) Sound clip and transcription of Hachijo