Early Modern Japanese

Early Modern Japanese (近世日本語, kinsei nihongo) was the stage of the Japanese language after Middle Japanese and before Modern Japanese.[1] It is a period of transition that shed many of the language's medieval characteristics and became closer to its modern form.

| Early Modern Japanese | |

|---|---|

| 近世日本語 | |

| Region | Japan |

| Era | Evolved into Modern Japanese in the mid-19th century |

Early forms | |

| Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

The period spanned roughly 250 years and extended from the 17th century to the first half of the 19th century. Politically, it generally corresponded to the Edo period.

Background

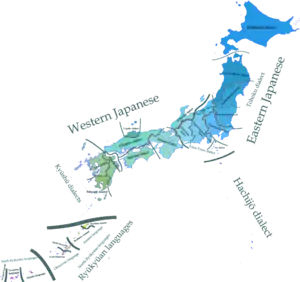

At the beginning of the 17th century, the center of government moved to Edo from Kamigata under the control of the Tokugawa shogunate. Until the early Edo period, the Kamigata dialect, the ancestor of the modern Kansai dialect, was the most influential dialect. However, in the late Edo period, the Edo dialect, the ancestor of the modern Tokyo dialect, became the most influential dialect, and Japan closed its borders to foreigners. Compared to the previous centuries, the Tokugawa rule brought about much newfound stability. That made the importance of the warrior class gradually fall and replaced it with the merchant class. There was much economic growth, and new forms of artistic developments appeared, such as Ukiyo-e, Kabuki, and Bunraku. That included new literary genres such as Ukiyozōshi, Sharebon (pleasure districts), Kokkeibon (commoners), and Ninjōbon developed. Major authors included Ihara Saikaku, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Matsuo Bashō, Shikitei Sanba, and Santō Kyōden.

Phonology

Vowels

There were five vowels: /i, e, a, o, u/.

- /i/: [i]

- /e/: [e]

- /a/: [a]

- /o/: [o]

- /u/: [ɯ]

In Middle Japanese, word-initial /e/ and /o/ were realized with the semivowels [j] and [w] before avowel, respectively , but became realized as simple vowels by the mid-18th century.[2]

The high vowels /i, u/ became voiceless [i̥, ɯ̥] between voiceless consonants or the end of a word, as was noted in a number of foreign texts:[3]

- Diego Collado Ars Grammaticae Iaponicae Lingvae (1632) gave word-final examples: gozàru > gozàr, fitòtçu > fitòtç, and àxi no fàra > àx no fàra.

- E. Kaempfer's Geschichte und Beschreibung von Japan (1777–1779) and C. P. Thunberg's Resa uti Europa, Africa, Asia (1788–1793) list word-medial examples: kurosaki > krosaki, atsuka > atska.

Long vowels

Middle Japanese had two types of long o: [ɔː] and [oː]. Both had merged into [oː] by the first half of the 17th century.[4] During the transition, instances of ɔː temporarily had a tendency to become short in the Kamigata dialect.[5][6]

- nomɔː > nomo "drink"

- hayɔː > hayo "quickly"

In addition, all of the other vowels could be lengthened because of various contractions in the Edo dialect.[7][8] Most are still used in Modern Japanese in both Tokyo and the rest of the Kanto region but are not part of Standard Japanese.

- /ai/ > [eː]: sekai > sekeː "world", saigo > seːgo "last"

- /ae/ > [eː]: kaeru > keːru "frog", namae > nameː "name"

- /oi/ > [eː]: omoɕiroi > omoɕireː

- /ie/ > [eː]: oɕieru > oɕeːru "teach"

- /ui/ > [iː]: warui > wariː

- /i wa/ > [jaː]: kiki wa > kikjaː "listening"

- /o wa/ > [aː]: nanzo wa > nanzaː "grammar"

The long /uː/ had been developed during Middle Japanese and has remained unchanged.

Consonants

Middle Japanese had the following consonants:

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɴ | ||||

| Fricative | ɸ | s z | ɕ | ç | h | ||

| Liquid | r | ||||||

| Approximant | j | ɰ |

/t, s, z, h/ all have a number of allophones before the high vowels [i, ɯ]:

- t → t͡ʃ / __i

- t → t͡s / __ɯ

- z → d͡ʒ / __i

- z → d͡z / __ɯ

- h → ç / __i

- h → ɸ / __ɯ

Several major developments occurred:

- /zi, di/ and /zu, du/, respectively, no longer contrasted.

- /h/ partially developed from [ɸ] into [h, ç].

- /se/ lost its palatalization and became [se].

Middle Japanese had a syllable final -t, which was gradually replaced by the open syllable /tu/.

Labialization

The labial /kwa, gwa/ merged with their non-labial counterparts into [ka, ga].[9]

Palatalization

The consonants /s, z/, /t/, /n/, /h, b/, /p/, /m/, and /r/ could be palatalized.

Depalatalization could also be seen in the Edo dialect:

- hyakunin issyu > hyakunisi

- /teisyu/ > /teisi/ "lord"

- /zyumyoː/ > /zimyoː/ "life"

Prenasalization

Middle Japanese had a series of prenasalized voiced plosives and fricatives: [ŋɡ, nz, nd, mb]. In Early Modern Japanese, they lost their prenasalization, which resulted in ɡ, z, d, b.

Grammar

Verbs

Early Modern Japanese has five verbal conjugations:

| Verb Class | Irrealis 未然形 |

Adverbial 連用形 |

Conclusive 終止形 |

Attributive 連体形 |

Hypothetical 仮定形 |

Imperative 命令形 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrigrade (四段) | -a | -i | -u | -u | -e | -e |

| Upper Monograde(上一段) | -i | -i | -iru | -iru | -ire | -i(yo, ro) |

| Lower Monograde (下一段) | -e | -e | -eru | -eru | -ere | -e(yo, ro) |

| K-irregular (カ変) | -o | -i | -uru | -uru | -ure | -oi |

| S-irregular (サ変) | -e, -a, -i | -i | -uru | -uru | -ure | -ei, -iro |

As had already begun in Middle Japanese, the verbal morphology system continued to evolve. The total number of verb classes was reduced from nine to five. Specifically, the r-irregular and n-irregular regularized as quadrigrade, and the upper and lower bigrade classes merged with their respective monograde. That left the quadrigrade, upper monograde, lower monograde, k-irregular, and s-irregular.[10]

Adjectives

There were two types of adjectives: regular adjectives and adjectival nouns.

Historically, adjective were subdivided into two classes: those whose adverbial form ended in -ku and those that ended in –siku. That distinction was lost in Early Modern Japanese.

| Irrealis 未然形 |

Adverbial 連用形 |

Conclusive 終止形 |

Attributive 連体形 |

Hypothetical 仮定形 |

Imperative 命令形 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -kara | -ku | -i | -i | -kere | -kare |

Historically, the adjectival noun was sub-divided into two categories: -nar and -tar. In Early Modern Japanese, -tar vanished and left only -na.

| Irrealis 未然形 |

Adverbial 連用形 |

Conclusive 終止形 |

Attributive 連体形 |

Hypothetical 仮定形 |

Imperative 命令形 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -da ra | -ni -de |

-na -da |

-na | -nare -nara |

Notes

- Shibatani (1990: 119)

- Nakata (1972: 238-239)

- Nakata (1972: 239-241)

- Nakata (1972: 256)

- Nakata (1972: 262-263)

- Yamaguchi (1997:116-117)

- Nakata (1972: 260-262)

- Yamaguchi (1997: 150-151)

- Yamamoto (1997: 147-148)

- Yamaguchi (1997:129)

References

- Kondō, Yasuhiro; Masayuki Tsukimoto; Katsumi Sugiura (2005). Nihongo no Rekishi (in Japanese). Hōsō Daigaku Kyōiku Shinkōkai. ISBN 4-595-30547-8.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1987). The Japanese Language Through Time. Yale University. ISBN 0-300-03729-5.

- Matsumura, Akira (1971). Nihon Bunpō Daijiten (in Japanese). Meiji Shoin. ISBN 4-6254-0055-4.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo (2003). Old Japanese : a phonetic reconstruction. London; New York: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-30575-6.

- Nakata, Norio (1972). Kōza Kokugoshi: Dai 2 kan: On'inshi, Mojishi (in Japanese). Taishūkan Shoten.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36918-5.

- Yamaguchi, Akiho; Hideo Suzuki; Ryūzō Sakanashi; Masayuki Tsukimoto (1997). Nihongo no Rekishi (in Japanese). Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppankai. ISBN 4-13-082004-4.