Japanese pitch accent

Japanese pitch accent (高低アクセント, kōtei akusento) is a feature of the Japanese language that distinguishes words by accenting particular morae in most Japanese dialects. The nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects. For instance, the word for "now" is [iꜜma] in the Tokyo dialect, with the accent on the first mora (or equivalently, with a downstep in pitch between the first and second morae), but in the Kansai dialect it is [i.maꜜ]. A final [i] or [ɯ] is often devoiced to [i̥] or [ɯ̥] after a downstep and an unvoiced consonant.

Standard Japanese

Normative pitch accent, essentially the pitch accent of the Tokyo Yamanote dialect, is considered essential in jobs such as broadcasting. The current standards for pitch accent are presented in special accent dictionaries for native speakers such as the Shin Meikai Nihongo Akusento Jiten (新明解日本語アクセント辞典) and the NHK Nihongo Hatsuon Akusento Jiten (NHK日本語発音アクセント辞典). Newsreaders and other speech professionals are required to follow these standards.

Foreign learners of Japanese are often not taught to pronounce the pitch accent, though it is included in some noted texts, such as Japanese: The Spoken Language. Incorrect pitch accent is a strong characteristic of a "foreign accent" in Japanese.

Scalar pitch

In standard Japanese, pitch accent has the following effect on words spoken in isolation:

- If the accent is on the first mora, then the pitch starts high, drops suddenly on the second mora, then levels out. The pitch may fall across both morae, or mostly on one or the other (depending on the sequence of sounds)—that is, the first mora may end with a high falling pitch, or the second may begin with a (low) falling pitch, but the first mora will be considered accented regardless. The Japanese describe this as 頭高 atamadaka (literally, "head-high").

- If the accent is on a mora other than the first or the last, then the pitch has an initial rise from a low starting point, reaches a near-maximum at the accented mora, then drops suddenly on any following morae. This accent is referred to as 中高 nakadaka ("middle-high").

- If the word has an accent on the last mora, the pitch rises from a low start up to a high pitch on the last mora. Words with this accent are especially distinguishable from accent-less words because the pitch immediately drops on a following particle such as が ga or に ni. In Japanese this accent is called 尾高 odaka ("tail-high").

- If the word doesn't have an accent, the pitch rises from a low starting point on the first mora or two, and then levels out in the middle of the speaker's range, without ever reaching the high tone of an accented mora. In Japanese this accent is named "flat" (平板 heiban).

Note that accent rules apply to phonological words, which include any following particles. So the sequence "hashi" spoken in isolation can be accented in two ways, either háshi (accent on the first syllable, meaning 'chopsticks') or hashí (flat or accent on the second syllable, meaning either 'edge' or 'bridge'), while "hashi" plus the subject-marker "ga" can be accented on the first syllable or the second, or be flat/accentless: háshiga 'chopsticks', hashíga 'bridge', or hashigá 'edge'.

In poetry, a word such as 面白い omoshirói, which has the accent on the fourth mora ro, is pronounced in five beats (morae). When initial in the phrase (and therefore starting out with a low pitch), the pitch typically rises on the o, levels out at mid range on the moshi, peaks on the ro, and then drops suddenly on the i, producing a falling tone on the roi.

In all cases but final accent, there is a general declination (gradual decline) of pitch across the phrase. This, and the initial rise, are part of the prosody of the phrase, not lexical accent, and are larger in scope than the phonological word. That is, within the overall pitch-contour of the phrase there may be more than one phonological word, and thus potentially more than one accent.

Binary pitch

The foregoing describes the actual pitch. In most guides, however, accent is presented with a two-pitch-level model. In this representation, each mora is either high (H) or low (L) in pitch, with the shift from high to low of an accented mora transcribed HꜜL.

- If the accent is on the first mora, then the first syllable is high-pitched and the others are low: HꜜL, HꜜL-L, HꜜL-L-L, HꜜL-L-L-L, etc.

- If the accent is on a mora other than the first, then the first mora is low, the following morae up to and including the accented one are high, and the rest are low: L-Hꜜ, L-HꜜL, L-H-HꜜL, L-H-H-HꜜL, etc.

- If the word is heiban (accentless), the first mora is low and the others are high: L-H, L-H-H, L-H-H-H, L-H-H-H-H, etc. This high pitch spreads to unaccented grammatical particles that attach to the end of the word, whereas these would have a low pitch when attached to an accented word (including one accented on the final mora). Although only the terms "high" and "low" are used, the high of an unaccented mora is not as high as an accented mora.

Downstep

Many linguists analyse Japanese pitch accent somewhat differently. In their view, a word either has a downstep or does not. If it does, the pitch drops between the accented mora and the subsequent one; if it does not have a downstep, the pitch remains more or less constant throughout the length of the word: That is, the pitch is "flat" as Japanese speakers describe it. The initial rise in the pitch of the word, and the gradual rise and fall of pitch across a word, arise not from lexical accent, but rather from prosody, which is added to the word by its context: If the first word in a phrase does not have an accent on the first mora, then it starts with a low pitch, which then rises to high over subsequent morae. This phrasal prosody is applied to individual words only when they are spoken in isolation. Within a phrase, each downstep triggers another drop in pitch, and this accounts for a gradual drop in pitch throughout the phrase. This drop is called terracing. The next phrase thus starts off near the low end of the speaker's pitch range and needs to reset to high before the next downstep can occur.

Examples of words that differ only in pitch

In standard Japanese, about 47% of words are unaccented and around 26% are accented on the ante-penultimate mora. However, this distribution is highly variable between word categories. For example, 70% of native nouns are unaccented, while only 50% of kango and only 7% of loanwords are unaccented. In general, most 1-2 mora words are accented on the first mora, 3-4 mora words are unaccented, and words of greater length are almost always accented on one of the last five morae.[1]

The following chart gives some examples of minimal pairs of Japanese words whose only differentiating feature is pitch accent. Phonemic pitch accent is indicated with the phonetic symbol for downstep, [ꜜ].

Romanization Accent on first mora Accent on second mora Accentless hashi はし /haꜜsi/

[háɕì] háshì箸 chopsticks /hasiꜜ/

[hàɕí] hàshí橋 bridge /hasi/

[hàɕí] hàshí端 edge hashi-ni はしに /haꜜsini/

[háɕìɲì] háshì-nì箸に at the chopsticks /hasiꜜni/

[hàɕíɲì] hàshí-nì橋に at the bridge /hasini/

[hàɕīɲī] hàshi-ni端に at the edge ima いま /iꜜma/

[ímà] ímà今 now /imaꜜ/

[ìmá] ìmá居間 living room kaki かき /kaꜜki/

[kákì] kákì牡蠣 oyster /kakiꜜ/

[kàkí] kàkí垣 fence /kaki/

[kàkí] kàkí柿 persimmon kaki-ni かきに /kaꜜkini/

[kákìɲì] kákì-nì牡蠣に at the oyster /kakiꜜni/

[kàkíɲì] kàkí-nì垣に at the fence /kakini/

[kàkīɲī] kàki-ni柿に at the persimmon sake さけ /saꜜke/

[sákè] sákè鮭 salmon /sake/

[sàké] sàké酒 alcohol, sake nihon にほん /niꜜhoɴ/

[ɲíhòɴ̀] níhòn二本 two sticks of /nihoꜜɴ/

[ɲìhóɴ̀] nìhón日本 Japan

In isolation, the words hashi はし /hasiꜜ/ hàshí "bridge" and hashi /hasi/ hàshí "edge" are pronounced identically, starting low and rising to a high pitch. However, the difference becomes clear in context. With the simple addition of the particle ni "at", for example, /hasiꜜni/ hàshí-nì "at the bridge" acquires a marked drop in pitch, while /hasini/ háshi-ni "at the edge" does not. However, because the downstep occurs after the first mora of the accented syllable, a word with a final long accented syllable would contrast all three patterns even in isolation: an accentless word nihon, for example, would be pronounced [ɲìhōɴ̄], differently from either of the words above. In 2014, a study recording the electrical activity of the brain showed that Japanese mainly use context, rather than pitch accent information, to contrast between words that differ only in pitch.[2]

This property of the Japanese language allows for a certain type of pun, called dajare (駄洒落, だじゃれ), combining two words with the same or very similar sounds but different pitch accents and thus meanings. For example, kaeru-ga kaeru /kaeruɡa kaꜜeru/ (蛙が帰る, lit. the frog will go home). These are considered quite corny, and are associated with oyaji gags (親父ギャグ, oyaji gyagu, dad joke).

Since any syllable, or none, may be accented, Tokyo-type dialects have N+1 possibilities, where N is the number of syllables (not morae) in a word, though this pattern only holds for a relatively small N.

| accented syllable | one-syllable word | two-syllable word | three-syllable word |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (no accent) |

/ki/ (気, mind) | /kaze/ (風, wind) | /tomeru/ (止める, to stop) |

| 1 | /kiꜜ/ (木, tree) | /haꜜru/ (春, spring) | /iꜜnoti/ (命, life) |

| 2 | — | /kawaꜜ/ (川, river) | /tamaꜜɡo/ (卵, egg) |

| 3 | — | /kotobaꜜ/ (言葉, word) | |

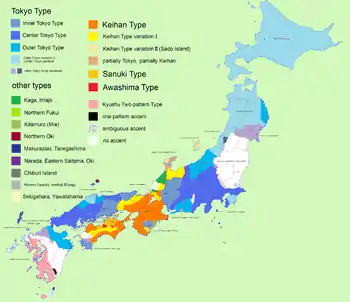

Other dialects

Accent and tone are the most variable aspect of Japanese dialects. Some have no accent at all; of those that do, it may occur in addition to a high or low word tone.[3]

The dialects that have a Tokyo-type accent, like the standard Tokyo dialect described above, are distributed over Hokkaido, northern Tohoku, most of Kanto, most of Chūbu, Chūgoku and northeastern Kyushu. Most of these dialects have a more-or-less high tone in unaccented words (though first mora has low tone, and following morae have high tone); an accent takes the form of a downstep, after which the tone stays low. But some dialects, for example, dialects of northern Tohoku and eastern Tottori, typically have a more-or-less low tone in unaccented words; accented syllables have a high tone, with low tone on either side, rather like English stress accent. In any case, the downstep has phonological meaning and the syllable followed by downstep is said to be "accented".

Keihan (Kyoto–Osaka)-type dialects of Kansai and Shikoku have nouns with both patterns: That is, they have tone differences in unaccented as well as accented words, and both downstep in some high-tone words and a high-tone accent in some low-tone words. In the neighboring areas of Tokyo-type and Keihan-type such as parts of Kyushu, northeastern Kanto, southern Tohoku, around Fukui, around Ōzu in Ehime and elsewhere, nouns are not accented at all.

Kyushu (two-pattern type)

In western and southern Kyushu dialects (pink area on the map on the right), a high tone falls on a predictable syllable, depending only on whether the noun has an accent. This is termed a two-pattern (nikei) system, as there are two possibilities, accented and not accented. For instance, in the Kagoshima dialect unaccented nouns have a low tone until the final syllable, at which point the pitch rises. In accented nouns, however, the penultimate syllable of a phonological word has a high tone, which drops on the final syllable. (Kagoshima phonology is based on syllables, not on morae.) For example, irogami 'colored paper' is unaccented in Kagoshima, while kagaribi 'bonfire' is accented. The ultimate or penultimate high tone will shift when any unaccented grammatical particle is added, such as nominative -ga or ablative -kara:

- [iɾoɡamí], [iɾoɡamiɡá], [iɾoɡamikaɾá]

- [kaɡaɾíbi], [kaɡaɾibíɡa], [kaɡaɾibikáɾa]

In the Shuri dialect of the old capital of Okinawa, unaccented words are high tone; accent takes the form of a downstep after the second syllable, or after the first syllable of a disyllabic noun.[4] However, the accents patterns of the Ryukyuan languages are varied, and do not all fit the Japanese patterns.

Nikei accents are also found in parts of Fukui and Kaga in Hokuriku region (green area on map).

No accent vs. one-pattern type

In Miyakonojō, Miyazaki (small black area on map), there is a single accent: all phonological words have a low tone until the final syllable, at which point the pitch rises. That is, every word has the pitch pattern of Kagoshima irogami. This is called an ikkei (one-pattern) accent. Phonologically, it is the same as the absence of an accent (white areas on map), and is sometimes counted as such, as there can be no contrast between words based on accent. However, speakers of ikkei-type dialects feel that they are accenting a particular syllable, whereas speakers of unaccented dialects have no such intuition.

Kyoto–Osaka (Keihan type)

Near the old capital of Kyoto, in Kansai, Shikoku, and parts of Hokuriku (the easternmost Western Japanese dialects), there is a more innovative system, structurally similar to a combination of these patterns. There are both high and low initial tone as well as the possibility of an accented mora. That is, unaccented nouns may have either a high or a low tone, and accented words have pitch accent in addition to this word tone. This system will be illustrated with the Kansai dialect of Osaka.

| accented mora | one mora | two-mora word | three-mora word | gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| high tone | (no accent) | /ki/ [kíí] | /kiɡa/ [kíɡá] | /kikara/ [kíkáɾá] | 'mind' (気) |

| — | /kaze/ [kázé] | /kazeɡa/ [kázéɡá] | 'wind' (風) | ||

| — | /jameru/ [jáméɾɯ́] | 'stop' (止める) | |||

| 1 | /hiꜜ/ [çíì] | /hiꜜɡa/ [çíɡà] | /hiꜜkara/ [çíkàɾà] | 'day' (日) | |

| — | /kaꜜwa/ [káwà] | /kaꜜwaɡa/ [káwàɡà] | 'river' (川) | ||

| — | /siꜜroi/ [ɕíɾòì] | 'be white' (白い) | |||

| 2 | — | (none) | /ataꜜma/ [átámà] | 'head' (頭) | |

| 3 | — | (few words, if any) | |||

| low tone | (no accent) | /˩ki/ [kìí] | /˩kiɡa/ [kìɡá] | /˩kikara/ [kìkàɾá] | 'tree' (木) |

| — | /˩ito/ [ìtó] | /˩itoɡa/ [ìtòɡá] | 'thread' (糸) | ||

| — | /˩okiru/ [òkìɾɯ́] | 'to get up' (起きる) | |||

| 2 | — | /˩haruꜜ/ [hàɾɯ́ ~ hàɾɯ̂] | /˩haruꜜɡa/ [hàrɯ́ɡà] | 'spring' (春) | |

| — | /˩kusuꜜri/ [kɯ̀sɯ́ɾì] | 'medicine' (薬) | |||

| 3 | — | /˩maQtiꜜ/ [màttɕí ~ màttɕî] | 'match' (マッチ) | ||

| Low tone is considered to be marked (transcribed /˩/). Not all patterns are found: In high-tone words, accent rarely falls on the last mora, and in low-tone words it cannot fall on the first. One-mora words are pronounced with long vowels. | |||||

Accented high-tone words in Osaka, like atama 'head', are structurally similar to accented words in Tokyo, except that the pitch is uniformly high prior to the downstep, rather than rising as in Tokyo.[5] As in Tokyo, the subsequent morae have low pitch. Unaccented high-tone words, such as sakura 'cherry tree', are pronounced with a high tone on every syllable, and in following unaccented particles:

- High tone /ataꜜma/, accent on ta: [átámà], [átámàɡà], [átámàkàɾà]

- High tone /sakura/, no accent: [sákɯ́ɾá], [sákɯ́ɾáɡá], [sákɯ́ɾákáɾá]

Low-tone accented words are pronounced with a low pitch on every mora but the accented one. They are like accented words in Kagoshima, except that again there are many exceptions to the default placement of the accent. For example, tokage is accented on the ka in both Osaka and Kagoshima, but omonaga 'oval face' is accented on mo in Osaka and na in Kagoshima (the default position for both dialects); also, in Osaka the accented is fixed on the mo, whereas in Kagoshima it shifts when particles are added. Unaccented low-tone words such as usagi 'rabbit' have high pitch only in the final mora, just as in Kagoshima:

- Low tone /˩omoꜜnaɡa/, accent on mo: [òmónàɡà], [òmónàɡàɡà], [òmónàɡàkàɾà]

- Low tone /˩usaɡi/, no accent: [ɯ̀sàɡí], [ɯ̀sàɡìɡá], [ɯ̀sàɡìkàɾá]

Hokuriku dialect in Suzu is similar, but unaccented low-tone words are purely low, without the rise at the end:

- /˩usaɡi/: [ɯ̀sàŋì], [ɯ̀sàŋìŋà], [ɯ̀sàŋìkàɾà];

sakura has the same pattern as in Osaka.

In Kōchi, low-tone words have low pitch only on the first mora, and subsequent morae are high:

- /˩usaɡi/: [ɯ̀sáɡí], [ɯ̀sáɡíɡá], [ɯ̀sáɡíkáɾá].

The Keihan system is sometimes described as having 2n+1 possibilities, where n is the number of morae (up to a relatively small number), though not all of these actually occur. From the above table, there are three accent patterns for one-mora words, four (out of a theoretical 2n+1 = 5) for two-mora words, and six (out of a theoretical 2n+1 = 7) for three-mora words.

Correspondences between dialects

There are regular correspondences between Tokyo-type and Keihan-type accents. The downstep on high-tone words in conservative Keihan accents generally occurs one syllable earlier than in the older Tokyo-type accent. For example, kokoro 'heart' is /kokoꜜro/ in Tokyo but /koꜜkoro/ in Osaka; kotoba 'word' is /kotobaꜜ/ in Tokyo but /kotoꜜba/ in Osaka; kawa 'river' is /kawaꜜ/ in Tokyo but /kaꜜwa/ in Osaka. If a word is unaccented and high-tone in Keihan dialects, it is also unaccented in Tokyo-type dialects. If a two-mora word has a low tone in Keihan dialects, it has a downstep on the first mora in Tokyo-type dialects.

In Tokyo, whereas most non-compound native nouns have no accent, most verbs (including adjectives) do. Moreover, the accent is always on the penultimate mora, that is, the last mora of the verb stem, as in /shiroꜜi/ 'be white' and /okiꜜru/ 'get up'. In Kansai, however, verbs have high- and low-tone paradigms as nouns do. High-tone verbs are either unaccented or are accented on the penultimate mora, as in Tokyo. Low-tone verbs are either unaccented or accented on the final syllable, triggering a low tone on unaccented suffixes. In Kyoto, verbal tone varies irregularly with inflection, a situation not found in more conservative dialects, even more conservative Kansai-type dialects such as that of Kōchi in Shikoku.[6]

Syllabic and moraic

Japanese pitch accent also varies in how it interacts with syllables and morae. Kagoshima is a purely syllabic dialect, while Osaka is moraic. For example, the low-tone unaccented noun shimbun 'newspaper' is [ɕìm̀bɯ́ɴ́] in Kagoshima, with the high tone spread across the entire final syllable bun, but in Osaka it is [ɕìm̀bɯ̀ɴ́], with the high tone restricted to the final mora n. In Tokyo, accent placement is constrained by the syllable, though the downstep occurs between the morae of that syllable. That is, a stressed syllable in Tokyo dialect, as in 貝 kai 'shell' or 算 san 'divining rod', will always have the pattern /kaꜜi/ [káì], /saꜜɴ/ [sáɴ̀], never */kaiꜜ/, */saɴꜜ/.[7] In Osaka, however, either pattern may occur: tombi 'black kite' is [tóm̀bì] in Tokyo but [tòḿbì] in Osaka.

References

- Labrune, Laurence (2012). The phonology of Japanese (Rev. and updated ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 186–188. ISBN 9780199545834.

- Tamaoka, K.; Saito, N.; Kiyama, S.; Timmer, K.; Verdonschot, R. G. (2014). "Is pitch accent necessary for comprehension by native Japanese speakers? An ERP investigation". Journal of Neurolinguistics. 27: 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroling.2013.08.001. S2CID 13831878.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Shimabukuro, Moriyo (1996). "Pitch in Okinawan Nouns and Noun Compounds". In Reves; Steele; Wong (eds.). Linguistics and Language Teaching: Proceedings of the Sixth Joint LSH–HATESL Conference.

- Phonetically, however, Tokyo accented words sound more like Osaka low-tone words, due to the initial low pitch in both.

- De Boer, Elisabeth (2008). "The Origin of Alternations in Initial Pitch in the Verbal Paradigms of the Central Japanese (Kyōto Type) Accent Systems". In Lubotsky; Schaeken; Wiedenhof (eds.). Evidence and Counter-Evidence. vol. 2.

- Although in other words with the moraic pattern of kai and san the second mora may have a high tone and the first a low tone, this is just the rise in pitch, in an unaccented word or before a downstep, spread across the syllable, and does not depend on whether that syllable consists of one mora or two. Unaccented ha 'leaf', for example, has a rising tone in Tokyo dialect, whereas accented ne 'root' has a falling tone; likewise unaccented kai 'buying' and san 'three' have a rising tone, wherease accented kai 'shell' and san 'divining rod' can only have a falling tone.

Bibliography

- Akamatsu, Tsutomu (1997). Japanese Phonetics: Theory and practice. Munichen: Lincom Europa.

- Bloch, Bernard (1950). "Studies in colloquial Japanese IV: Phonemics". Language. 26 (1): 86–125. doi:10.2307/410409. JSTOR 410409.

- Haraguchi, Shosuke (1977). The Tone Pattern of Japanese: An Autosegmental Theory of Tonology. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

- Haraguchi, Shosuke (1999). "Accent". In Tsujimura, N. (ed.). The Handbook of Japanese Linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ch. 1, pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-0-631-20504-3.

- 平山 輝男. 全国アクセント辞典 (in Japanese). Tokyo: 東京堂.

- NHK日本語発音アクセント辞典 (in Japanese). Tokyo: NHK放送文化研究所.

- Kindaiichi, Haruhiko (1995). Shin Meikai Akusento Jiten 新明解アクセント辞典 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Sanseidō.

- Kubozono, Haruo (1999). "Mora and syllable". In Tsujimura, N. (ed.). The Handbook of Japanese Linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ch. 2, pp. 31–61. ISBN 978-0-631-20504-3.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1975). A Reference Grammar of Japanese. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- McCawley, James D. (1968). The Phonological Component of a Grammar of Japanese. The Hague: Mouton.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vance, Timothy (1987). An Introduction to Japanese Phonology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Japanese/Pitch accent |