Tibitó

Tibitó is the second-oldest dated archaeological site on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia.[4] The rock shelter is located in the municipality Tocancipá, Cundinamarca, Colombia, in the northern part of the Bogotá savanna. At Tibitó, bone and stone tools (knives and scrapers mostly) and carbon have been found. Bones from Haplomastodon, Cuvieronius, Cerdocyon and white tailed deer from the deepest human trace containing layer of the site is carbon dated to be 11,740 ± 110 years old. The oldest dated sediments are lacustrine clays from an ancient Pleistocene lake.

Location within Colombia | |

| Location | Tocancipá, Cundinamarca |

|---|---|

| Region | Bogotá savanna Altiplano Cundiboyacense |

| Coordinates | 4°59′08.4″N 73°58′58.4″W |

| Altitude | 2,555 m (8,383 ft)[1] |

| Type | Rock shelter |

| Part of | Pre-Muisca sites |

| History | |

| Material | Stone & bone tools Carbon |

| Founded | ~11,850 BP |

| Periods | Prehistory-Herrera |

| Cultures | Preceramic-Herrera |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Gonzalo Correal Urrego[2][3] |

Principal research at Tibitó was carried out by Colombian archaeologist Gonzalo Correal Urrego, who also analysed other early sites Tequendama, Aguazuque and El Abra.[2]

Background

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense, and its southeastern flat portion the Bogotá savanna, were populated by the first humans in the late Pleistocene, as evidenced by finds in Pubenza (16,000 years BP), El Abra, Tibitó and others. Until roughly 30,000 years BP, the Bogotá savanna was covered by a large lake; Lake Humboldt. This glacial lake surrounded by snowy peaks was fed by the glaciers of Sumapaz in the south, based on analysis of debris flow deposits close to Fusagasugá, yielding ages between 40,000 and 7000 years BP.[5] The approximately 4,500 square kilometres (1,700 sq mi) large lake contained an island, presently known as the Suba Hills (Cerros de Suba), in Bogotá. Surrounding the lake, Pleistocene megafauna as Glyptodonts, giant sloths, mastodons and deer foraged. The lake retreated during the last 30,000 years, but remnants still existing today are the Bogotá River and its tributaries, Lake Herrera and the many Wetlands of Bogotá. The timber line around Lake Humboldt, in older texts named Lake Bogotá, has been estimated to have been 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) lower than today.[6]

During the latest Pleistocene and early Holocene, the first humans arrived on the Andean high plateau at 2,650 metres (8,690 ft) above sea level. They settled in caves and rock shelters in various locations on the Altiplano and had a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The main ingredient of the early diet existing until colonial times was white tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Fishing in the many lakes that existed in those times was another source of food for the people.

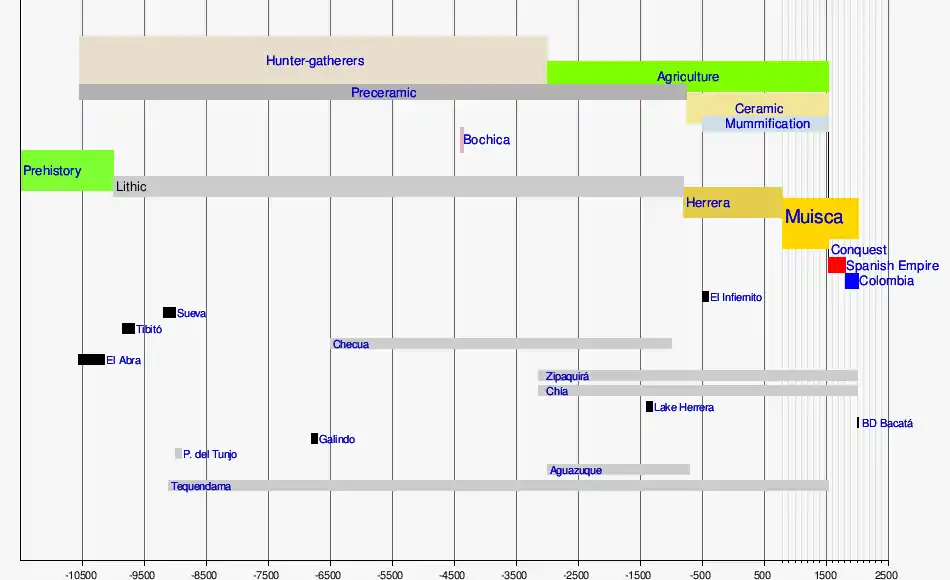

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

.png.webp) |

Description

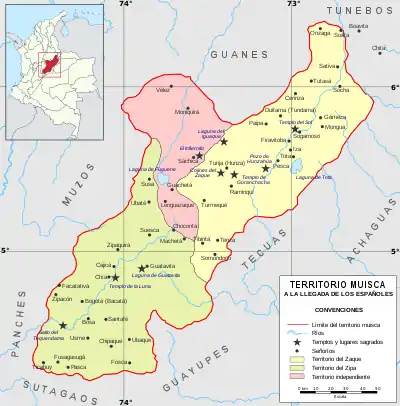

Radiocarbon dating of a deeper lacustrine clay in the sequence of Tibitó revealed the site was in a lake environment around 52,000 years BP.[7] Pleistocene lakes also existed in the Ubaté-Chiquinquirá Valley to the northwest and in the valley of Soatá, in the lower altitude northeasternmost part of the Muisca Confederation.[8] The paleoclimate changed over the course of the latest Pleistocene and the Upper Pleniglacial was relatively humid, eroding earlier lagunal clays. The latest stage of the Pleniglacial was characterised by a cold and dry climate. In the valleys, hunter-gatherers lived. The original topography was covered in the Guantivá interstadial and El Abra stadial by humic sediments.[9]

At Tibitó remains of the extinct Pleistocene megafauna Cuvieronius, Haplomastodon and Equus amerhippus and extant white tailed deer and crab-eating fox have been found set in a circle. The bones were burnt and unburnt and mixed with stone artifacts and limestone chunks. The most important finds of Cuvieronius come from the Eastern Cordillera, with main sites Tibitó and Mosquera.[10] 156 unifacial stone artifacts, of which 41% knives,[11] pieces of carbon and bone tools have been found and analysed by Gonzalo Correal Urrego.[12][13] Ninetynine percent of the finds were from local origin.[14] The bones, showing a relative higher abundance of Haplomastodon than Cuvieronius and the extinct American horse,[11] have been carbon dated to be 11,740 ± 110 years old.[4] This was confirmed by palynological analysis, that also indicated a páramo climate at the time.[3][15] This makes the site slightly younger than the oldest; El Abra, dated at 12,400 ± 160 years BP.[4]

See also

References

- Google Maps Elevation Finder

- Correal Urrego, 1990

- Cooke, 1988, p.180

- (in Spanish) Caracterización de los sitios arqueológicos Sabana de Bogotá - ICANH

- Hoyos et al., 2015, p.265

- Zonneveld, 1968, p.205

- Vogel & Lerman, 1969, p.358

- Villarroel et al., 2001, p.79

- Scott & Meyers, 1994, p.390

- Prado et al., 2003, p.353

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p.76

- Dillehay, 1999, p.208

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p.74

- Gnecco & Aceituno, 2004, p.155

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p.77

Bibliography

- Cooke, Richard. 1998. Human settlement of Central America and northernmost South America (14,000-8000 BP). Quaternary International 49/50. 177–190.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Evidencias culturales durante el Pleistocene y Holoceno de Colombia - Cultural evidences during the Pleistocene and Holocene of Colombia. Revista de Arqueología Americana 1. 69–89. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Dillehay, Tom M. 1999. The Late Pleistocene Cultures of South America. Evolutionary Anthropology _. 206–216.

- Gnecco, Cristóbal, and Javier Aceituno. 2004. Poblamiento temprano y espacios antropogénicos en el norte de Suramérica - Early peopling and anthropogenic spaces in the northern South America. Complutum 15. 151–164.

- Montes, Natalia; O. Monsalve; G.W. Berger; J.L. Antinao; H. Giraldo; C. Silva; G. Ojeda; G. Bayona, and J. Escobar. 2015. A climatic trigger for catastrophic Pleistocene–Holocene debris flows in the Eastern Andean Cordillera of Colombia. Journal of Quaternary Science 30. 258–270.

- Prado, José Luis; María Teresa Alberdi; Begoña Sánchez, and Beatríz Azanza. 2003. Diversity of the Pleistocene Gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea) from South America. Deinsea 9. 347–363.

- Scott, David A., and Pieter Meyers. 1994. Archaeometry of Pre-Columbian sites and artifacts, 1–437. The Getty Conservation Institute.

- Villarroel, Carlos; Ana Elena Concha, and Carlos Macía. 2001. El Lago Pleistoceno de Soatá (Boyacá, Colombia): Consideraciones estratigráficas, paleontológicas y paleoecológicas. Geología Colombiana 26. 79–93.

- Vogel, J.C., and J.C Lerman. 1969. Groningen Radiocarbon Dates VIII. Radiocarbon II. 351–390.

- Zonneveld, Jan Isaak Samuel. 1968. Quaternary climatic changes in the Caribbean and N. South America, 203–208.

Further reading

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 2002. Evidencias Culturales Pleistocénicas y del Temprano Holoceno en la Cordillera Oriental de Colombia: Periodización Tentativa - Cultural evidences of the Pleistocene and Early Holocene in the Eastern Ranges of Colombia: tentative timing, 63–73. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1-316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Groot de Mahecha, Ana María. 1992. Checua: Una secuencia cultural entre 8500 y 3000 años antes del presente - Checua: a cultural sequence between 8500 and 3000 years before present, 1-95. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Hammen, Thomas van der; Gonzalo Correal Urrego, and Gert Jaap van Klinken. 1990. Isótopos estables y dieta del hombre prehistórico en la sabana de Bogotá - Stable isotopes and diet of the prehistoric man on the Bogotá savanna. Boletín de arqueología 2. 3-10.

- Hammen, Thomas van der, and Gonzalo Correal Urrego. 2003. Supervivencia de mastodontes, megaterios y presencia del hombre en el Valle del Magdalena (Colombia) entre 6000 y 5000 A.P. - Survival of mastodonts, megatheriums and the presence of man in the Magdalena Valley (Colombia) between 6000 and 5000 years BP. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. 27. 159-164. Accessed 2016-07-08.

.jpg.webp)