Titanoboa

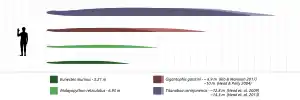

Titanoboa (/tiˌtɑːnoʊˈboʊə/) is an extinct genus of very large snakes that lived in what is now La Guajira in northeastern Colombia. They could grow up to 12.8 m (42 ft) long and reach a weight of 1,135 kg (2,500 lb).[1]

| Titanoboa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of a Titanoboa dorsal vertebra in the Geological Museum José Royo y Gómez, Bogotá | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Boidae |

| Genus: | †Titanoboa Head et al., 2009 |

| Species: | †T. cerrejonensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Titanoboa cerrejonensis Head et al., 2009 | |

Fossils of Titanoboa have been found in the Cerrejón Formation,[2] and date to around 58 to 60 million years ago. The giant snake lived during the Middle to Late Paleocene epoch,[3] a 10-million-year period immediately following the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.[4]

The only known species is Titanoboa cerrejonensis, the largest snake ever discovered,[3] which supplanted the previous record holder, Gigantophis.

Etymology

The name Titanoboa means "titanic boa".[1] The species epithet cerrejonensis refers to the Cerrejón coal mine and the Cerrejón Formation, in which the fossils have been found.

Description

By comparing the sizes and shapes of its fossilized vertebrae to those of extant snakes, researchers estimated that the largest individuals of T. cerrejonensis found had a total length around 12.8 m (42 ft) and weighed about 1,135 kg (2,500 lb; 1.12 long tons; 1.25 short tons).[1]

Naming and discovery

In 2009, the fossils of 28 individuals of T. cerrejonensis were found in the Cerrejón Formation of the coal mines of Cerrejón in La Guajira, Colombia.[1][3] Before this discovery, few fossils of Paleocene-epoch vertebrates had been found in ancient tropical environments of South America.[5] The snake was discovered on an expedition by a team of international scientists led by Jonathan Bloch, a University of Florida vertebrate paleontologist, and Carlos Jaramillo, a paleobotanist from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama.[4]

The name Titanoboa means "titanic boa".[1] The species epithet cerrejonensis refers to the Cerrejón coal mine and the Cerrejón Formation, in which the fossils have been found.

Habitat

Titanoboa inhabited the first recorded tropical forest in South America. It shared its ecosystem with large Crocodylomorpha and large turtles. The paleogeography of the Late Paleocene was a sheltered paralic (coastal) swamp area, sheltered by the emerging later Guajira hills in the west and the slowly rising present-day Serranía del Perijá in the east, with an open connection to the proto-Caribbean in the north.[6] In this environment the tropical aquatic ferns of the genus Salvinia flourished, as evidenced by fossils found in Cerrejón, the Bogotá Formation and the Palermo Formation.[7]

Palaeobiology

While initially thought to have been an apex predator of the Paleocene ecosystem in which it lived, analysis of the cranial elements of Titanoboa possess unique features relative to other boids. These features include high palatal and marginal tooth position counts, low-angled quadrate orientation, and reduced palatine-pterygoid and ptery. This has pointed to the genus being dominantly piscivorous; a trait unique to Titanoboa among all boids.[8]

The size of T. cerrejonensis has also provided clues as to the earth's climate during its existence; because snakes are ectothermic, the discovery implies that the tropics, the creature's habitat, must have been warmer than previously thought, averaging about 32 °C (90 °F).[1][3][9][10]

The warmer climate of the Earth during the time of T. cerrejonensis allowed cold-blooded snakes to attain much larger sizes than modern snakes.[11] Today, larger ectothermic animals are found in the tropics, where it is hottest, and smaller ones are found farther from the equator.[4]

Other researchers disagree with the above climate estimate. For example, a 2009 study in the journal Nature applying the mathematical model used in the above study to an ancient lizard fossil from temperate Australia predicts that lizards currently living in tropical areas should be capable of reaching 10 to 14 m (33 to 46 ft), which is not the case.[12]

In another critique published in the same journal, Mark Denny, a specialist in biomechanics, noted that the snake was so large and was producing so much metabolic heat that the ambient temperature must have been four to six degrees cooler than the current estimate, or the snake would have overheated.[13]

In popular culture

.jpg.webp)

On 22 March 2012, a full-scale-model replica of a 14.6 m (48 ft), 1,135 kg (2,500 lb) Titanoboa was displayed in Grand Central Terminal in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York. It was a promotion for a TV show on the Smithsonian Channel called Titanoboa: Monster Snake which aired on 1 April 2012.[14][15]

References

- Head et al., 2009

- Titanoboa cerrejonensis at Fossilworks.org

- Kwok, R. (4 February 2009). "Scientists find world's biggest snake". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2009.80.

- "At 2,500 Pounds And 43 Feet, Prehistoric Snake Is Largest On Record". Science Daily. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Maugh II, T.H. (4 February 2009). "Fossil of 43-foot super snake Titanoboa found in Colombia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Pérez Consuegra et al., 2017, p.95

- Pérez Consuegra et al., 2017, p.85

- Head et al., 2013, p.141

- Joyce, C. (5 February 2009). "1-Ton Snakes Once Slithered In The Tropics". NPR. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Shellito, C.J.; Sloan, L.C.; Huber, M. (2003). "Climate model sensitivity to atmospheric CO2 levels in the Early–Middle Paleogene". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 193 (1): 113–123. Bibcode:2003PPP...193..113S. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(02)00718-6.

- Makarieva et al., 2005

- Sniderman, 2009

- Head, 2009

- "Titanoboa: Monster Snake". Smithsonian Channel. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- "Titanoboa: Monster Snake - History's Deadliest Predators". Youtube. Smithsonian Channel. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

Regional geology

- Ayala, R.C.; G. Bayona; A. Cardona; C. Ojeda; O.C. Montenegro; C. Montes; V. Valencia, and C. Jaramillo. 2012. The paleogene synorogenic succession in the northwestern Maracaibo block: Tracking intraplate uplifts and changes in sediment delivery systems. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 39. 93–111. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Bayona, Germán; Agustín Cardona; Carlos Jaramillo; Andrés Mora; Camilo Montes; Victor Valencia; Carolina Ayala; Omar Montenegro, and Mauricio Ibañez Mejía. 2012. Early Paleogene magmatism in the northern Andes: Insights on the effects of Oceanic Plateau–continent convergence. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 331-332. 97–111. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Cediel, Fabio; Robert P. Shaw, and Carlos Cáceres. 2003. Tectonic assembly of the Northern Andean Block, in C. Bartolini, R. T. Buffler, and J. Blickwede, eds., The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon habitats, basin formation, and plate tectonics. AAPG Memoir 79. 815–848. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Iturralde Vinent, Manuel A., and R.D.E. MacPhee. 1999. Paleogeography of the Caribbean Region: Implications for Cenozoic Biogeography. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 238. 1–95. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Jaillard, Etiénne; Thierry Sempere; Pierre Soler; Gabriel Carlier, and René Marocco. 1995. The role of Tethys in the evolution of the northern Andes between Lake Permian and Late Eocene times. The Ocean Basins and Margins 8. 463–492. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Pindell, James L., and Kenneth D. Tabbutt. 1995. Mesozoic-Cenozoic Andean Paleogeography and Regional Controls on Hydrocarbon Systems in Petroleum Basins of South America. AAPG Memoir 62. 101–128. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Woodburne, Michael O; Francisco J. Goin; Mariano Bond; Alfredo A. Carlini; Javier N. Gelfo; Guillermo M. López; A. Iglesias, and Ana N. Zimicz. 2014. Paleogene Land Mammal Faunas of South America; a Response to Global Climatic Changes and Indigenous Floral Diversity. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 21. 1–73. Accessed 2017-05-22.

Local geology

- Denny, Mark W.; Brent L. Lockwood, and George Somero. 2009. Can the giant snake predict palaeoclimate?. Nature 460. 715–717. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Herrera, F.; C. Jaramillo, and S.L. Wing. 2005. Warm (not hot) tropics during the Late Paleocene: First continental evidence, 51C–0608. 86; Proceedings of American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting, San Francisco, California, USA. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Makarieva, Anastassia M.; Victor G. Gorshkov, and Bai-Lian Li. 2005. Gigantism, temperature and metabolic rate in terrestrial poikilotherms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 272. 2325–2328. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Rodríguez García, Gabriel, and Ana Cristina Londoño. 2002. Mapa geológico del departamento de La Guajira, 1–259. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-05-22.

Paleobiology Titanoboa

- Head, Jason; Jonathan Bloch; Jorge Moreno Bernal; Aldo Fernando Rincón Burbano, and Jason Bourque. 2013. Cranial osteology, body size, systematics, and ecology of the giant Paleocene snake Titanoboa cerrejonensis, 140–141. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Head, J.J.; J.I. Bloch; A.K. Hastings; J.R. Bourque; E.A. Cadena; F.A. Herrera; P.D. Polly, and C.A. Jaramillo. 2009. Giant boid snake from the paleocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures. Nature 457. 715–718. Accessed 2017-05-22.

Paleobiology other flora and fauna

- Cadena, Edwin A.; Daniel T. Ksepka; Carlos A. Jaramillo, and Jonathan I. Bloch. 2012a. New pelomedusoid turtles from the late Palaeocene Cerrejon Formation of Colombia and their implications for phylogeny and body size evolution. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10. 313–331. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Cadena, Edwin A.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2012b. New bothremydid turtle (Testudines, Pleurodira) from the Paleocene of northeastern Colombia. Journal of Paleontology 86. 688–698. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Cadena, Edwin A.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2010. New Podocnemidid Turtle (Testudines: Pleurodira) from the Middle-Upper Paleocene of South America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30. 367–382. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Hastings, Alexander K.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2014. A new blunt-snouted dyrosaurid, Anthracosuchus balrogus gen. et sp. nov. (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia), from the Palaeocene of Colombia. Historical Biology 27. 998–1020. Accessed 2017-03-30.

- Hastings, Alexander K.; Jonathan I. Bloch, and Carlos A. Jaramillo. 2011. A new longirostrine Dyrosaurid (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of north-eastern Colombia: Biogeographocal and behavioural implications for New-World Dyrosayridae. Palaeontology 54. 1095–1116. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Herrera, Fabiany; Steven R. Manchester; Mónica R. Carvalho; Carlos Jaramillo, and Scott L. Wings. 2014. Paleocene wind-dispersed fruits and seeds from Colombia and their implications for early Neotropical rainforests. Acta Paleobotanica 54. 197–229. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Herrera, Fabiany A.; Carlos A. Jaramillo; David L. Dilcher; Scott L. Wing, and Carolina Gómez N.. 2008. Fossil Araceae from a Paleocene neotropical rainforest in Colombia. American Journal of Botany 95. 1569–1583. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Pérez Consuegra, Nicolás; Aura Cuervo Gómez; Camila Martínez; Camilo Montes; Fabiany Herrera; Santiago Madriñán, and Carlos Jaramillo. 2017. Paleogene Salvinia (Salviniaceae) from Colombia and their paleobiogeographic implications. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 246. 85–108. Accessed 2017-10-21.

- Sniderman, J.M.K. 2009. Biased reptilian palaeothermometer?. Nature 460. E1. Accessed 2017-05-22.

- Wing, Scott L.; Fabiany Herrera; Carlos A. Jaramillo; Carolina Gómez Navarro; Peter Wilf, and Conrad C. Labandeira. 2009. Late Paleocene fossils from the Cerrejón Formation, Colombia, are the earliest record of Neotropical rainforest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106. 18627–18632. Accessed 2017-05-22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Titanoboa. |

- Jane O'Brien (2 April 2012). "The giant snake that stalked the Earth". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Nina Rastogi (10 February 2009). "A Snake the Size of a Plane: How did prehistoric animals get so big?". Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Titanoboa: Monster Snake at IMDb

.jpg.webp)