Bacatá

Bacatá is the name given to the main settlement of the Muisca Confederation on the Bogotá savanna. It mostly refers to an area, rather than an individual village, although the name is also found in texts referring to the modern settlement of Funza, in the centre of the savanna. Bacatá, alternatively written as Muequetá or Muyquytá, was the main seat of the zipa, the ruler of the Bogotá savanna and adjacent areas. The name of the Colombian capital, Bogotá, is derived from Bacatá, but founded as Santafe de Bogotá in the western foothills of the Eastern Hills in a different location than the original settlement Bacatá, west of the Bogotá River, eventually named after Bacatá as well.

Bacatá

Muyquytá or Muequetá | |

|---|---|

Main seat of the zipa | |

| Etymology: Chibcha: "(enclosure) outside the farmfields" | |

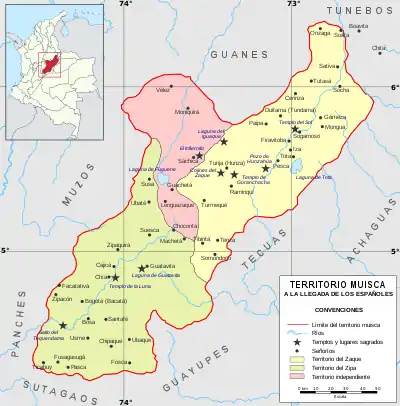

Map of the Muisca Confederation | |

Bacatá Location of Bacatá on the Bogotá savanna | |

| Coordinates: 4°42′59″N 74°12′44″W | |

| Country | Colombia |

| Department | Cundinamarca |

| Populated | Herrera Period |

| Founded by | Muisca |

| Government | |

| • Zipa | Tisquesusa († 1537) Sagipa († 1539) |

| Elevation | 2,550 m (8,370 ft) |

| Geography | Bogotá savanna Altiplano Cundiboyacense Eastern Ranges Colombian Andes |

The word is a combination of the Chibcha words bac, ca and tá, and means "(enclosure) outside the farmfields", referring to the rich agricultural lands of the Sabana Formation on the Bogotá savanna. Bacatá was submitted to the Spanish Empire by the conquistadors led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada on April 20, 1537. Santafe de Bogotá, the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada, was formally founded on August 6, 1538. The last zipa of an independent Bacatá was Tisquesusa, who died after being stabbed by a Spanish soldier. His brother, Sagipa, succeeded him and served as last zipa under Spanish rule.

The name Bacatá is maintained in the highest skyscraper of Colombia, BD Bacatá, and in the important fossil find in the Bogotá Formation; Etayoa bacatensis.

Etymology

The word Bacatá is Chibcha, the language of the indigenous Muisca, who inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense before the Spanish conquest. The word is a combination of bac or uac,[1] ca,[2] and tá,[3] meaning "outside", "enclosure" and "farmfield(s)" respectively. The name is translated as "(enclosure) outside the farmfields", or "limit of the farmfields".[4]

Alternative spellings are Muequetá, or Muyquytá,[5] and the word is transliterated in Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada as Bogothá.[6]

Background

The high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, is an area with an average elevation of 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) above sea level, populated since the prehistorical era. The first evidences of human settlement date to the Latest Pleistocene at 12,500 years BP. The oldest dated rock shelters are the pre-Clovis sites El Abra and Tibitó in the northern part of the fertile Bogotá savanna. During the occupation phases of these sites, the area experienced a páramo paleoclimate. Pleistocene megafauna as Cuvieronius hyodon, Haplomastodon waringi and Equus lasallei populated the Bogotá savanna and served as prey for the first human occupants.[7]

When the climate after the Last Glacial Maximum became more favourable during the early Holocene, human settlement shifted from caves and rock shelters to open area sites where primitive circular living spaces were constructed using bones and skin of the then still abundant white-tailed deer. Early open area sites are Checua, Aguazuque and Galindo. Other rock shelters such as Tequendama, in the south of the Bogotá savanna, remained populated or used for temporary settlement during this preceramic period.[8]

The fertile soils of the Bogotá savanna, sediments of the Sabana Formation, deposited in a lacustrine environment as a result of the Pleistocene Lake Humboldt, proved favourable for agriculture, that was introduced to the people by migrants probably from Peru and Central America. The earliest evidences of agriculture have been found in Zipacón, to the west of Bacatá, and date back to 2800 years BP. Dating to around the same time, ceramics has been uncovered,[9] and the ceramic period was named Herrera Period, after Lake Herrera, ranging from 800 BCE to 800 AD, with regional variations in time.[10]

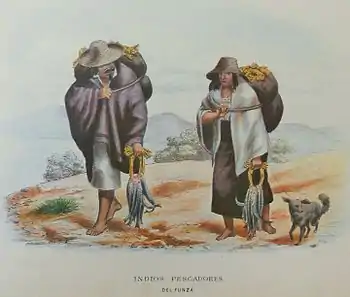

The time after 800 is called Muisca, in the indigenous language Muysccubun meaning "people" or "person"; the language did not have separate singular and plural designated words. During the phase of the Muisca, technological advancement of earlier established agricultural techniques, precise archaeoastronomical knowledge, a more developed social structure and a rich religion and mythology evolved on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. The Muisca were renowned traders with their neighbouring indigenous groups and developed a subsistence economy on the Altiplano. Main sources of their economy were agriculture and especially salt, that was extracted using large pots heated over fires from brines mined mainly in Zipaquirá and Nemocón. This process, an exclusive task of the Muisca women, gave the people the name "The Salt People". The high-quality salt was used as trade commodity with other indigenous groups, for the conservation of fish and meat and as spice in their cuisine.[11] Other products used for barter trade were coca, gold and emeralds.[12]

The Muisca were known as skilled gold workers, producing a variety of golden figurines with the tunjos as most abundant artefacts. These votive figures were used in the religious rituals of the people around the main sacred sites on the Altiplano. The many lakes, wetlands and rivers, remainders of Lake Humboldt, on the Bogotá savanna were cherished as products of their gods. An important lake for the Muisca was Lake Guatavita, a circular lake at an altitude of 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) to the northeast of present-day Guatavita. This lake formed the basis for the -not so much- legend of El Dorado; the "city or man of gold". At the initiation of the new zipa, a ritual was organised where he covered himself with gold dust and jumped into the ice cold waters of the lake from a raft. This ritual is represented in the famous Muisca raft, main artefact in the Museo del Oro in the Colombian capital.[13]

The flatlands of the Bogotá savanna were dotted with several small settlements consisting of 10 to 100 bohíos. The people constructed temples to honour their main deities; Sué (the Sun) and his wife Chía, the Moon. Another important deity for the Muisca was Bochica, who according to their mythology prevented the main river of the Bogotá savanna, the Bogotá River, from frequent overflowings by creating the Tequendama Falls. The present course of the Bogotá River is just east and south of Bacatá, a main settlement in the centre of the savanna. Analysis of the top soils surrounding the Bogotá River in proximity to Bacatá revealed several raised terrains used for agriculture.[14]

Muisca Confederation

The name Muisca Confederation has been given to the loose collection of caciques who governed several small settlements on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the times before the Spanish conquest. The area of roughly 25,000 square kilometres (9,700 sq mi) was subdivided into main cacicazgos, with as most important from northeast to southwest the terrains of Tundama around Tundama, the iraca of Suamox, the zaque of Hunza and the zipa of Bacatá.[15]

The Spanish chroniclers describe a system of tributes or subordinate cacicazgos on the Bogotá savanna; dependencies of the zipa of Bacatá. The villages of Simijaca, Guachetá, Ubaté, Chocontá, Nemocón, Zipaquirá, Guatavita, Suba, Ubaqué, Tibacuy, Fusagasugá, Pasca, Cáqueza, Teusacá, Tosca, Guasca, and Pacho are described as part of the Bacatá rule.[16] Other researchers, as Carl Henrik Langebaek and John Michael Francis, have revised the idea of tributes and attribute the term to a translation error of the Spanish writers. The Muysccubun verb "to give, to present" was zebquisca and the word for "to give" was zequasca, zemnisca or zequitusuca.[17]

Modern anthropologists, such as Jorge Gamboa Mendoza, attribute the present-day knowledge about the "confederation" and its organization more to a reflection by Spanish chroniclers who predominantly wrote about it a century or more after the Muisca were conquered. He proposed the idea of a loose collection of different people with slightly different languages and backgrounds rather than a strictly hierarchical organisation like the Aztec and Inca Empires.[18]

Zipa of Bacatá

| Zipa | Start | End | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meicuchuca | ~1450 | 1470 |

| Saguamanchica | 1470 | 1490 |

| Nemequene | 1490 | 1514 |

| Tisquesusa | 1514 | 1537 |

| Sagipa | 1537 | 1539 |

The zipa was the name of the leader of the southern part of the Muisca Confederation, mainly the Bogotá savanna and adjacent areas. As the Muisca lacked a written script, only the most recent zipas of the pre-Columbian period are known. The first reported zipa was Meicuchuca, who reigned from Bacatá between approximately 1450 and 1470. Much of his life is mythological, with the legend of the snake as main story.[19] His reign was followed by his nephew, Saguamanchica. At the start of his government, Saguamanchica submitted the neighbouring Sutagao to the south of the Bogotá savanna in the Battle of Pasca. Approximately twenty years later, Saguamanchica went to war with the zaque of Hunza, Michuá and both leaders were killed in the Battle of Chocontá, fought around 1490.[20]

Saguamanchica was succeeded by Nemequene, who according to the biographies about him held a brutal reign over his people. One of his accomplishments was the installation of the Nemequene Code, a code of conduct with severe punishments for those who didn't comply with the laws he drafted.[21] Possibly the salt mining village of Nemocón was named after Nemequene, who died around the year 1514 and was succeeded by Tisquesusa. The latter was the zipa of Bacatá until the moment the first Europeans appeared in the Muisca Confederation, in March 1537. The light-skinned strangers came from the north after a strenuous expedition of almost a year where they lost more than 80 percent of their soldiers. The Spanish conquistadors brought horses, an unknown animal for the Muisca and especially the horse riders were feared by the people who thought the rider and the horse were one entity. Also the dogs the Spanish conquerors brought on their journey created fear in the hearts of the humble humans.[22]

Conquest and colonial period

Tisquesusa received a prophecy from one of the caciques in the southern Muisca Confederation; he would "die, bathing in his own blood". When the zipa was informed of the advancing Spanish strangers, he fled his main seat in Bacatá. The Spanish found the place abandoned and promptly founded the village of Funza on April 20, 1537, ending the reign of the zipa in Bacatá.[23][24]

Tisquesusa was stabbed by one of the soldiers of the Spanish troops and fled towards the western hills bordering the Bogotá savanna. As the prophecy had predicted, he died alone and bathing in his own blood in the hills of Facatativá. His body was discovered much later. At the turn of the rule of Bacatá, the government was taken over by Sagipa, Tisquesusa's brother. This succession was against the norm of the Muisca, where the eldest son of the sister of the previous zipa would become the new ruler. The Spanish used this anomaly to set the Muisca up against Sagipa, also known as Zaquesazipa, and pressured him to pay tributes to the treasurers of the Spanish Empire. The new rulers of the Bogotá savanna used the eternal enemies of the Muisca, the Panche who inhabited the western slopes of the Eastern Ranges towards the Magdalena River, as bait to lure Sagipa into a battle allied with the Spanish, the Battle of Tocarema, fought on August 19 and 20, 1537. The between 12,000 and 20,000 guecha warriors of the last zipa.[25] together with "between 50 and not more than 100" Spanish soldiers defeated the Panche who posed powerful resistance thanks to their knowledge of the rugged terrain.[26][27]

The official foundation of Santafe de Bogotá, named after Bacatá, on August 6, 1538, by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and his troops, terminated the period of Bacatá as "capital" of the southern Muisca. The city was founded in the present-day centre of the Colombian city as capital of the New Kingdom of Granada. Sagipa, dethroned as ruler of Bacatá, received continuous threats from the Spanish after the victory, to hand over the valuable treasures of the Muisca; golden objects, cotton mantles and emeralds. When Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada left the New Kingdom of Granada with two other conquistadors in northern South America, who had reached the Bogotá savanna in early 1539, in May 1539, he left the rule of Bogotá and the colony in the hands of his younger brother, Hernán Pérez de Quesada. Hernán, with the assistance of his fellow conquistadors tortured Sagipa by burning his feet to have him give up his valuables. The last zipa of Bacatá did not survive these torments and died in the Spanish camp at Bosa in 1539, ending the rule of the indigenous Muisca on the Bogotá savanna.[28]

The bloodline of Bacatá was maintained in one of the first mestizo marriages in the New Kingdom of Granada; Sagipa's daughter, described as Magdalena de Guatavita, married conquistador Hernán Venegas Carrillo and the couple got four children; María, Fernán, Isabel and Alonso Venegas.[29] In a twist of fate, the latter, grandson of Sagipa; Alonso as descendant of Bacatá, killed Spanish conquistador and encomendero of Bogotá Gonzalo García Zorro in a duel in 1566.[30]

Named after Bacatá

- Hotel Bacatá, former hotel in the business centre of Bogotá, replaced by BD Bacatá

- BD Bacatá, the highest skyscraper of Colombia[31]

- Etayoa bacatensis, ungulate fossil found in the Paleocene-Eocene Bogotá Formation to the south of the Bogotá savanna[32][33]

- Pegoscapus bacataensis, a species of fig wasp, endemic to the Bogotá savanna[34]

- Bacatá appears as the name of the ruling class of the Muisca playable nation in the grand strategy game Europa Universalis IV[35]

- Bogotá and its derivatives, a transliteration of Muequetá, Muyquytá, Bacatá or Bogothá

References

- (in Spanish) uac – Muysccubun Dictionary online

- (in Spanish) ca – Muysccubun Dictionary online

- (in Spanish) ta – Muysccubun Dictionary online

- Correa, 2005, p. 213

- (in Spanish) Muyquytá – Muysccubun Dictionary online

- Epítome, p. 85

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 77

- Correal Urrego, 1990, p. 10

- Argüello García, 2015, p. 56

- (in Spanish) Chronology of pre-Columbian periods: Herrera and Muisca

- Daza, 2013, p. 26

- Langebaek, 1985, p. 5

- (in Spanish) Simbolos de la nación – Balsa Muisca y El Dorado – Museo del Oro, Bogotá

- Kruschek, 2003, p. 58

- Gómez Londoño, 2005, p. 285

- Gómez Londoño, 2005, p. 281

- Francis, 1993, p. 55

- Gamboa Mendoza, 2016

- (in Spanish) Biografía Meicuchuca – Pueblos Originarios

- (in Spanish) Biografía Saguamanchica – Pueblos Originarios

- (in Spanish) Biografía Nemequene – Pueblos Originarios

- Epítome, p. 87

- (in Spanish) Biografía Tisquesusa – Pueblos Originarios

- (in Spanish) Official website Funza Archived 2015-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Herrera Ángel, 2006, p. 128

- (in Spanish) La Batalla de Tocarema Archived 2017-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Battle of Tocarema – Universidad de los Andes

- (in Spanish) Biografía Sagipa – Pueblos Originarios

- (in Spanish) Periplo atlántico del cromosoma "Y" de Hernán Venegas Carrillo Manosalbas

- (in Spanish) Gonzalo García Zorro – Banco de la República – Soledad Acosta Samper

- (in Spanish) Cinco edificios que llevan en su nombre la historia indígena de Bogotá

- Etayoa bacatensis at Fossilworks.org

- Villarroel, 1987, p. 241

- Jansen González & Sarmiento, 2008

- Muisca names Europa Universalis IV

Bibliography

- Argüello García, Pedro María. 2015. Subsistence economy and chiefdom emergence in the Muisca area. A study of the Valle de Tena (PhD), 1–193. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Correa, François. 2005. El imperio muisca: invención de la historia y colonialidad del poder – The Muisca empire: invention of history and power colonialisation in "Muiscas: representaciones, cartografías y etnopolíticas de la memoria", 201–226. Universidad La Javeriana.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Evidencias culturales durante el Pleistocene y Holoceno de Colombia – Cultural evidences during the Pleistocene and Holocene of Colombia. Revista de Arqueología Americana 1. 69–89. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Daza, Blanca Ysabel. 2013. Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre Colombia y España – History of the integration process of foods between Colombia and Spain (PhD), 1–494. Universitat de Barcelona.

- Francis, John Michael. 1993. "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (M.A.), 1–118. University of Alberta.

- Gamboa Mendoza, Jorge. 2016. Los muiscas, grupos indígenas del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Una nueva propuesta sobre su organizacíon socio-política y su evolucíon en el siglo XVI – The Muisca, indigenous groups of the New Kingdom of Granada. A new proposal on their social-political organization and their evolution in the 16th century. Museo del Oro. Accessed 2017-04-17.

- Gómez Londoño, Ana María. 2005. Lo muisca: el diseño de una cartografía de centro. Chigys Mie: el mundo de los muiscas recreado por la condesa alemana Gertrud von Podewils Dürniz in "Muiscas: representaciones, cartografías y etnopolíticas de la memoria", 248–291. Universidad La Javeriana.

- Herrera Ángel, Marta. 2006. Transición entre el ordenamiento territorial prehispánico y el colonial en la Nueva Granada. Historia Crítica 32. 118–152.

- Jansen González, Sergio, and Carlos Eduardo Sarmiento. 2008. A new species of high mountain Andean fig wasp (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae) with a detailed description of its life cycle. Symbiosis 45. 135–141. Accessed 2017-04-17.

- Kruschek, Michael H. 2003. The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PhD), 1–271. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1985. Cuando los muiscas diversificaron la agricultura y crearon el intercambio – When the Muisca diversified the agriculture and created the exchange, 1–8. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Villarroel A., Carlos. 1987. Características y afinadas de Etayoa n. gen., tipo de una nueva familia de Xenungulata (Mammalia) del Paleoceno Medio (?) de Colombia. Comunicaciones Paleontológicas del Museo de Historia Natural de Montevideo 19. 241–254. Accessed 2017-03-29.

- N, N. 1979 (1889) (1539). Epítome de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada, 81–97. Banco de la República. Accessed 2017-04-17.

.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)