Slendro

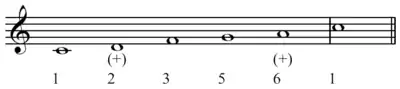

Slendro (Javanese: ꦱ꧀ꦭꦺꦤ꧀ꦢꦿꦺꦴ, romanized: Sléndro) (Sundanese: ᮞᮜᮦᮔ᮪ᮓ᮪ᮛᮧ, romanized: Saléndro) is a pentatonic scale, ![]() Play the older of the two most common scales (laras) used in Indonesian gamelan music, the other being pélog. In Javanese the term is said to derive either from "Sailendra", the name of the ruling family in the eighth and ninth centuries when Borobudur was built, or from its earlier being given by the god Sang Hyang Hendra.[3]

Play the older of the two most common scales (laras) used in Indonesian gamelan music, the other being pélog. In Javanese the term is said to derive either from "Sailendra", the name of the ruling family in the eighth and ninth centuries when Borobudur was built, or from its earlier being given by the god Sang Hyang Hendra.[3]

Tuning

From one region of Indonesia to another the slendro scale often varies widely. The amount of variation also varies from region to region. For example, slendro in Central Java varies much less from gamelan to gamelan than it does in Bali, where ensembles from the same village may be tuned very differently. The five pitches of the Javanese version are roughly equally spaced within the octave.

As in pelog, although the intervals vary from one gamelan to the next, the intervals between notes in a scale are very close to identical for different instruments within the same gamelan. It is common in Balinese gamelan that instruments are played in pairs which are tuned slightly apart so as to produce interference beating which are ideally at a consistent speed for all pairs of notes in all registers. It is thought that this contributes to the very "busy" and "shimmering" sound of gamelan ensembles. In the religious ceremonies that contain gamelan, these interference beats are meant to give the listener a feeling of a god's presence or a stepping stone to a meditative state.

For the instruments that do not need fixed pitches (such as suling and rebab) and the voice, other pitches are sometimes inserted into the scale. The Sundanese musicologist/teacher Raden Machjar Angga Koesoemadinata identified 17 vocal pitches used in slendro.[4] These microtonal adjustments bear some similarity to Indian śruti.

Note names

In Java, the notes of the slendro scale can be designated in different ways; one common way is the use of numbers often called by their names in Javanese, especially in a shortened form. An older set uses names derived from parts of the body. Notice that both systems have the same designations for 5 and 6. There is no 4; possibly this is because it appears as an unusual tone in pelog and is not used when modulating between the systems.

| Number | Javanese number | Traditional name | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Short name | Full name | Literal meaning | |

| 1 | siji | ji | panunggal | head |

| 2 | loro | ro | gulu | neck |

| 3 | telu | lu | dhadha | chest |

| 5 | lima | ma | lima | hand (five fingers) |

| 6 | enam | nam | nem | six |

The name barang is also sometimes used for 1 in slendro (it is the usual name for 7 in pelog); the octave is then designated as barang alit.

In Bali, the scale starts on the note named ding, and then continue going up the scale to dong, deng, dung and dang.

Connotations

For experienced participants in gamelan music, the pelog and slendro scales each have a particular feeling, related to the rituals and circumstances in which the scale is used. For example, in Bali, slendro is felt to have a sad sound because it is used as the tuning of gamelan angklung, the traditional ensemble for cremation ceremonies.

The connotation also depends on the pathet (roughly, the mode) used. There are three slendro pathet used in Javanese gamelan, nem, sanga, and manyura. That is the order in which they appear in a wayang performance, which historically used only slendro pathet. Consequently, they have the implications of where they appear in the evening.

Origin

The origin of the slendro scale is unknown. However the name slendro is derived from Sailendra, the ancient dynasty of Medang Kingdom in Central Java and also Srivijaya. The slendro scale is thought to be brought to Srivijaya by Mahayana Buddhist from Gandhara of India, via Nalanda and Srivijaya from there to Java and Bali.[5] It is similar to scales used in Indian and Chinese music as well as other areas of Asia and they all may have a common origin. A salendro scale is also found in the neighboring musical ensemble of Kulintang. This is very difficult if not impossible to determine.

Even within Indonesia it is difficult to determine the evolution of scales. For example, scales used in Banyuwangi, at the eastern tip of Java, are very similar to scales used in Jembrana, a short distance away on Bali. There is probably no way to document which region influenced the other, or if they both evolved together.

See also

References

- "The representations of slendro and pelog tuning systems in Western notation shown above should not be regarded in any sense as absolute. Not only is it difficult to convey non-Western scales with Western notation, but also because, in general, no two gamelan sets will have exactly the same tuning, either in pitch or in interval structure. There are no Javanese standard forms of these two tuning systems." Lindsay, Jennifer (1992). Javanese Gamelan, p.39-41. ISBN 0-19-588582-1.

- Leeuw, Ton de (2005). Music of the Twentieth Century, p.128. ISBN 90-5356-765-8.

- Lindsay (1992), p.38.

- Raden Machjar Angga Koesoemadinata. Ringkěsan Pangawikan Riněnggaswara. Jakarta: Noordhoff-Kollff, c. 1950, page 17. Cited in Hood, Mantle (1977). The Nuclear Theme as a Determinant of Pathet in Javanese Music, . New York: Da Capo.

- Gamelan: cultural interaction and musical development in central Java

Further reading

- Hewitt, Michael. Musical Scales of the World. The Note Tree. 2013. ISBN 978-0957547001.