Chinese musicology

Chinese musicology is the academic study of traditional Chinese music. This discipline has a very long history. Traditional Chinese music can be traced back to around 8,000 years ago during the Neolithic age. The concept of music, called 乐 (yuè), stands among the oldest categories of Chinese thought, however, in the known sources it does not receive a fairly clear definition until the writing of the Classic of Music (lost during the Han dynasty).

| Music of China | |

|---|---|

| |

| General topics | |

| |

| Genres | |

| Specific forms | |

| Media and performance | |

| Music festivals | Midi Modern Music Festival |

| Music media |

|

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | |

| National anthem | |

| Regional music | |

Music scales

The first musical scales were derived from the harmonic series. On the Guqin (a traditional instrument) all of the dotted positions are equal string length divisions related to the open string like 1/2, 1/3, 2/3, 1/4, 3/4, etc. and are quite easy to recognize on this instrument. The Guqin has a scale of 13 positions all representing a natural harmonic position related to the open string.

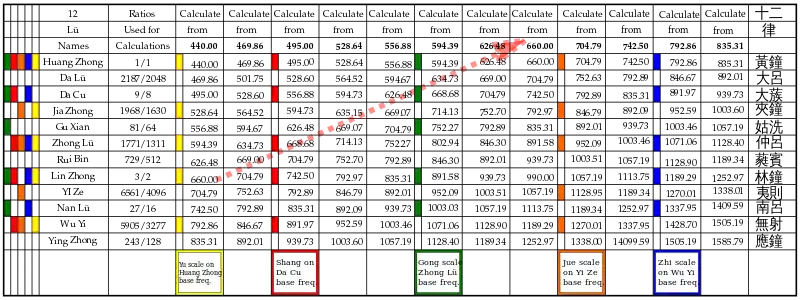

The ancient Chinese defined, by mathematical means, a gamut or series of 十二律 (Shí-èr-lǜ), meaning twelve lǜ, from which various sets of five or seven frequencies were selected to make the sort of "do re mi" major scale familiar to those who have been formed with the Western Standard notation. The 12 lü approximate the frequencies known in the West as the chromatic scale, from A, then B-flat, through to G and A-flat.

Scale and tonality

Most Chinese music uses a pentatonic scale, with the intervals (in terms of lǜ) almost the same as those of the major pentatonic scale. The notes of this scale are called gōng 宫, shāng 商, jué 角, zhǐ 徵 and yǔ 羽. By starting from a different point of this sequence, a scale (named after its starting note) with a different interval sequence is created, similar to the construction of modes in modern Western music.

Since the Chinese system is not an equal tempered tuning, playing a melody starting from the lǜ nearest to A will not necessarily sound the same as playing the same melody starting from some other lǜ, since the wolf interval will occupy a different point in the scale. The effect of changing the starting point of a song can be rather like the effect of shifting from a major to a minor key in Western music. The scalar tunings of Pythagoras, based on 2:3 ratios (8:9, 16:27, 64:81, etc.), are a western near-parallel to the earlier calculations used to derive Chinese scales.

Sources

- 陈应时 (Chen Yingshi, Shanghai Conservatory). "一种体系 两个系统 Yi zhong ti-xi, liang ge xi-tong". Musicology in China. 2002 (4): 109–116.