Wilfrid Laurier

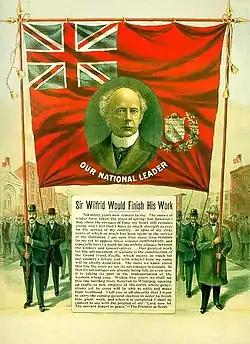

Sir Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier GCMG, PC, KC (/ˈlɒrieɪ/ LORR-ee-ay; French: [wilfʁid loʁje]; 20 November 1841 – 17 February 1919) was a Canadian politician and statesman who served as the seventh prime minister of Canada, in office from 11 July 1896 to 6 October 1911.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier | |

|---|---|

_cropped.jpg.webp) Laurier in 1906 | |

| 7th Prime Minister of Canada | |

| In office 11 July 1896 – 6 October 1911 | |

| Monarch | |

| Governor General | |

| Preceded by | Charles Tupper |

| Succeeded by | Robert Borden |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier 20 November 1841 Saint-Lin, Canada East |

| Died | 17 February 1919 (aged 77) Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Notre Dame Cemetery, Ottawa, Ontario |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Other political affiliations | Laurier Liberal (1917–19) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Education | McGill University (LL.L., 1864) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

Laurier is often considered one of the country's greatest statesmen. He is well-known for his policies of conciliation, expanding Confederation, and compromise between French and English Canada. His vision for Canada was a land of individual liberty and decentralized federalism. He also argued for an English–French partnership in Canada. "I have had before me as a pillar of fire," he said, "a policy of true Canadianism, of moderation, of reconciliation." He passionately defended individual liberty, "Canada is free and freedom is its nationality," and "Nothing will prevent me from continuing my task of preserving at all cost our civil liberty." Laurier was also well-regarded for his efforts to establish Canada as an autonomous country within the British Empire, and he supported the continuation of the Empire if it was based on "absolute liberty political and commercial". In addition, he was a strict nationalist, argued for a more competitive Canada through limited government, and was an adherent of fiscal discipline.[1] A 2011 Maclean's historical ranking of the Prime Ministers placed Laurier first.[2]

Canada's first francophone prime minister, Laurier holds a number of records. He is tied with Sir John A. Macdonald for the most consecutive federal elections won (four), and his 15-year tenure remains the longest unbroken term of office among prime ministers. In addition, his nearly 45 years (1874–1919) of service in the House of Commons is a record for that house.[3] At 31 years, 8 months, Laurier was the longest-serving leader of a major Canadian political party, surpassing William Lyon Mackenzie King by over two years. Along with King, he also holds the distinction of serving as Prime Minister during the reigns of three Canadian Monarchs.[4] Finally, he is the fourth-longest serving Prime Minister of Canada, behind King, Macdonald, and Pierre Trudeau. Laurier's portrait has been displayed on the Canadian five-dollar note since 1972.

Early life

The second child of Carolus Laurier and Marcelle Martineau, Wilfrid Laurier was born in Saint-Lin, Canada East (modern day Saint-Lin-Laurentides, Quebec), on 20 November 1841. Laurier was among the seventh generation of his family in Canada. He was a sixth-generation Canadian. His ancestor François Cottineau, dit Champlaurier, came to Canada from Saint-Claud, France. He grew up in a family where politics was a staple of talk and debate. His father, an educated man having liberal ideas, enjoyed a certain degree of prestige about town. In addition to being a farmer and surveyor, he also occupied such sought-after positions as mayor, justice of the peace, militia lieutenant and school board member. At the age of 11, Wilfrid left home to study in New Glasgow, a neighbouring village largely inhabited by immigrants from Scotland. Over the next two years, he familiarized himself with the mentality, language and culture of British people. Laurier attended the Collège de L'Assomption and graduated in law from McGill University in 1864.[5]

.jpg.webp)

He was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Quebec from Drummond-Arthabaska in the 1871 Quebec general election, but resigned on 19 January 1874, to enter federal politics in the riding of Quebec East.[6] He was first elected to the House of Commons of Canada in the 1874 election, serving briefly in the Cabinet of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie as Minister of Inland Revenue.

Leadership

Chosen as leader of the federal Liberal Party in 1887, he gradually built up his party's strength through his personal following both in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada. He led the Liberal Party to victory in the 1896 election, and contested five other federal elections; he remained Prime Minister until the defeat of the Liberal Party by the Conservative Party in the 1911 election.

Quebec stronghold

By 1909, Laurier had been able to build the Liberal Party a base in Quebec, which had remained a Conservative stronghold for decades due to the province's social conservatism and to the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, which distrusted the Liberals' anti-clericalism. The growing alienation of French Canadians from the Conservative Party due to its links with anti-French, anti-Catholic Orangemen in English Canada aided the Liberal Party.[7] These factors, combined with the collapse of the Conservative Party of Quebec, gave Laurier an opportunity to build a stronghold in French Canada and among Catholics across Canada.

Catholic priests in Quebec repeatedly warned their parishioners not to vote for Liberals. Their slogan was "le ciel est bleu, l'enfer est rouge" (heaven is blue/Conservative, hell is red/Liberal).[8]

Prime Minister (1896–1911)

Laurier led Canada during a period of rapid growth, industrialization, and immigration. His long career straddles a period of major political and economic change. As Prime Minister, he was instrumental in ushering Canada into the 20th century and in gaining greater autonomy from Britain for his country. A list of his Ministers is available at the Parliamentary website,[9] and is known as the 8th Canadian Ministry.

One of Laurier's first acts as Prime Minister was to implement a solution to the Manitoba Schools Question, which had helped to bring down the Conservative government of Charles Tupper earlier in 1896. The Manitoba legislature had passed a law eliminating public funding for Catholic schooling (thereby going against the federal constitutional Manitoba Act, 1870, which guaranteed Catholic and Protestant religious education rights). The Catholic minority asked the federal government for support, and eventually, the Conservatives proposed remedial legislation to override Manitoba's legislation. Laurier opposed the remedial legislation on the basis of provincial rights and succeeded in blocking its passage by Parliament. Once elected, Laurier proposed a compromise stating that Catholics in Manitoba could have a Catholic education if there were enough students to warrant it (10 students in the school), known as the Laurier-Greenway Compromise, on a school-by-school basis. This was seen by many as the best possible solution in the circumstances, making both the French and English equally satisfied. Laurier called his effort to lessen the tinder in this issue "sunny ways" (French: voies ensoleillées).[10]

In 1899, the United Kingdom expected military support from Canada, as part of the British Empire, in the Second Boer War. Laurier was caught between demands for support for military action from English Canada, and a strong opposition from French Canada which saw the Boer War as an "English" war and to some degree appreciated the similar places that Boers and French Canadians held in the British Empire. Henri Bourassa was an especially vocal opponent. Laurier eventually decided to send a volunteer force, rather than the militia expected by Britain, but Bourassa continued to oppose any form of military involvement.

Laurier visited the United Kingdom in 1902, and took part in the 1902 Colonial Conference and the coronation of King Edward VII on 9 August 1902. While in Europe, he also visited France to negotiate on trade with the French government.[11]

In 1905, Laurier oversaw Saskatchewan and Alberta's entry into Confederation, the last two provinces to be created out of the Northwest Territories.[12] This followed the enactment of the Yukon Territory Act by the Laurier Government in 1898, separating the Yukon from the Northwest Territories.[13]

Laurier presided over the Quebec Bridge disaster, in which 75 workers were killed, on 29 August 1907.

On 29 July 1910, while in Saskatoon to attend the opening of the University of Saskatchewan, he bought a newspaper from a young John Diefenbaker, a future Conservative Prime Minister. The young Diefenbaker, recognizing the Prime Minister, shared his ideas for the country and amused him. He inquired about the young man's business and expressed the hope that he would be a great man someday. The boy ended the conversation by saying, "Well, Mr. Prime Minister, I can't waste any more time on you. I must get back to work."[14]

In August 1911, Wilfrid Laurier approved the order-in-council P.C. 1911-1324 recommended by Minister of the Interior, Frank Oliver and approved by the cabinet on 12 August 1911. The order was intended to keep out Black Americans escaping segregation in the American south, stating that "the Negro race...is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada." The order was never called upon, as efforts by immigration officials had already reduced the number of Blacks migrating to Canada. The order was canceled on 5 October 1911, the day before Laurier completed his term, by cabinet claiming that the Minister of the Interior was not present at the time of approval.[15]

Naval Bill

The naval competition between the United Kingdom and the German Empire escalated in the early years of the 20th century. The British asked Canada for more money and resources for ship construction, precipitating a heated political division in Canada. The British supporters wished to send as much as possible, whereas those against wished to send nothing.

Aiming for compromise, Laurier advanced the Naval Service Act of 1910 which created the Naval Service of Canada. The navy would initially consist of five cruisers and six destroyers; in times of crisis, it could be made subordinate to the British Royal Navy. The idea was lauded at the 1911 Imperial Conference in London, but it proved unpopular across the political spectrum in Canada, especially in Quebec as ex-Liberal Henri Bourassa organized an anti-Laurier force.

Reciprocity and defeat

In 1911, another controversy arose regarding Laurier's support of trade reciprocity with the United States. His long-serving Minister of Finance, William Stevens Fielding, reached an agreement allowing for the free trade of natural products. This had the strong support of agricultural interests, but it alienated many businessmen who formed a significant part of the Liberals' support base. The Conservatives denounced the deal and played on long-standing fears that reciprocity could eventually lead to the American annexation of Canada.

Contending with an unruly House of Commons, including vocal disapproval from Liberal MP Clifford Sifton, Laurier called an election to settle the issue of reciprocity. The Conservatives were victorious and Robert Laird Borden succeeded Laurier as Prime Minister.

Opposition and war

Laurier led the opposition during World War I. He led the filibuster to the Conservatives' own Naval Bill which would have sent contributions directly to the British Navy; the bill was later blocked by the Liberal-controlled Senate. He was an influential opponent of conscription, which led to the Conscription Crisis of 1917 and the formation of a Union government, which Laurier refused to join for fear of having Quebec fall in the hands of nationalist Henri Bourassa. However, many Liberals, particularly in English Canada, joined Borden as Liberal-Unionists and the "Laurier Liberals" were reduced to a mostly French-Canadian rump as a result of the 1917 election.

However, Laurier's last policies and efforts had not been in vain. As a result of Laurier's opposition of conscription in 1917, Quebec and its French-Canadian voters voted overwhelmingly to support the Liberal party starting in 1917. Despite one notable exception in 1958, the Liberal party continued to dominate federal politics in Quebec until 1984. His protege and successor as party leader William Lyon Mackenzie King led the Liberals to a landslide victory over the Conservatives in the 1921 election.

Personal life and death

Wilfrid Laurier married Zoé Lafontaine in Montreal on 13 May 1868. She was the daughter of G.N.R. Lafontaine and his first wife, Zoé Tessier known as Zoé Lavigne. Laurier's wife Zoé was born in Montreal and educated there at the School of the Bon Pasteur, and at the Convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart, St. Vincent de Paul. The couple lived at Arthabaskaville until they moved to Ottawa in 1896. She served as one of the vice presidents on the formation of the National Council of Women and was honorary vice president of the Victorian Order of Nurses.[16] The couple had no children.

Beginning in 1878 and for some twenty years while married to Zoé, Laurier had an "ambiguous relationship" with a married woman, Émilie Barthe.[17] Where Zoé loved plants, animals and home life, she was not an intellectual; Émilie was, and relished literature and politics like Wilfrid, whose heart she won. Rumour had it he fathered a son, Armand Lavergne, with her, yet Zoé remained with him until his death.

Laurier died of a stroke on 17 February 1919, while still in office as Leader of the Opposition. Though he had lost a bitter election two years earlier, he was loved nationwide for his "warm smile, his sense of style, and his "sunny ways"."[18] Some 50,000 people jammed the streets of Ottawa as his funeral procession marched to his final resting place at Notre Dame Cemetery.[19][20][21] His remains would eventually be placed in a stone sarcophagus, adorned by sculptures of nine mourning female figures, representing each of the provinces in the union. His wife, Zoé Laurier, died in 1921 and was placed in the same tomb.

National Historic Sites

Laurier is commemorated by three National Historic Sites.

The Sir Wilfrid Laurier National Historic Site is in his birthplace, Saint-Lin-Laurentides, a town 60 km (37 mi) north of Montreal, Quebec. Its establishment reflected an early desire to not only mark his birthplace (a plaque in 1925 and a monument in 1927), but to create a shrine to Laurier in the 1930s. Despite early doubts and later confirmation that the house designated as the birthplace was neither Laurier's nor on its original site, its development, and the building of a museum, satisfied the goal of honoring the man and reflecting his early life.[22]

His brick residence in Ottawa is known as Laurier House National Historic Site, at the corner of what is now Laurier Avenue and Chapel Street. In their will, the Lauriers left the house to Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who in turn donated it to Canada upon his death. Both sites are administered by Parks Canada as part of the national park system.

The 1876 Italianate residence of the Lauriers during his years as a lawyer and Member of Parliament, in Victoriaville, Quebec, is designated Wilfrid Laurier House National Historic Site, owned privately and operated as the Laurier Museum.[23][24][25]

In November 2011, Wilfrid Laurier University located in Waterloo, Ontario, unveiled a statue depicting a young Wilfrid Laurier sitting on a bench, thinking.[26]

Recognition

Laurier had titular honours including:

- the prenominal "The Honourable" and the postnominal "PC" for life by virtue of being made a member of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada on 8 October 1877.[27]

- His prenominal was upgraded to "The Right Honourable" when he was made a member of the Imperial Privy Council of the United Kingdom in the 1897 Diamond Jubilee Honours

- the prenominal "Sir" and postnominal "GCMG" as a knight grand cross of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, bestowed in the 1897 Diamond Jubilee Honours

- The honorary degree LL.D. from the University of Edinburgh and the Freedom of the City of Edinburgh on 26 July 1902, when he visited the city while in the country for the coronation of King Edward VII.[28]

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Day is observed each year on 20 November, his birth date[29]

- Laurier is depicted on several banknotes issued by the Bank of Canada:

- The $1,000 note in the 1935 Series and 1937 Series

- The $5 note in the Scenes of Canada series, 1972 and 1979, Birds of Canada series, 1986, Journey series, 2002 and Frontier series, 2013

- Laurier has appeared on at least three postage stamps, issued in 1927 (two) and 1973

Many sites and landmarks were named to honor Laurier. They include:

- Mount Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the highest peak in British Columbia's Premier Range, near Mount Robson

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Elementary, located in Vancouver, British Columbia

- Laurier Avenue, located in Milton, Ontario

- Avenue Laurier, located in Shawinigan, Quebec

- Laurier Boulevard, and Laurier Hill, located in Brockville, Ontario

- Avenue Laurier, located in Montreal, Quebec

- Boulevard Laurier, located in Quebec City, Quebec

- Laurier Avenue, located in Ottawa, Ontario

- Laurier Avenue, located in Deep River, Ontario

- Laurier Street, located in North Bay, Ontario

- Rue Laurier, located in Casselman, Ontario

- Rue Laurier Street, located in Rockland, Ontario

- The Laurier Heights neighbourhood, including Laurier Drive and Laurier Heights School, in Edmonton, Alberta

- Laurier Drive, located in Saskatoon's Confederation Park neighbourhood, where the majority of the streets are named after former Canadian prime ministers

- The provincial electoral district of Laurier-Dorion (an honour shared with Canadian politician Antoine-Aimé Dorion)

- The federal electoral district of Laurier—Sainte-Marie

- On 1 November 1973, Waterloo Lutheran University, one of Ontario's publicly funded universities, located in Waterloo, Ontario, was renamed Wilfrid Laurier University; the university has since added a campus in Brantford, Ontario

- A Montreal Metro station, Laurier (Montreal Metro)

- CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier

- Chateau Laurier, a downtown Ottawa hotel of high reputation and a national historic site

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Public School in Markham, Ontario

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board, an English school board located in Quebec; the school board serves the Laval, Laurentides, and Lanaudière regions in Quebec

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Secondary School in London, Ontario

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Secondary School in Ottawa, Ontario

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Collegiate Institute in Scarborough, Ontario

- Laurier was ranked No. 3 of the Prime Ministers of Canada (out of the 20 through Jean Chrétien) in the survey by Canadian historians included in Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders by J.L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer.

Supreme Court appointments

Laurier chose the following jurists to be appointed as justices of the Supreme Court of Canada by the Governor General:

- Sir Louis Henry Davies (25 September 1901 – 1 May 1924)

- David Mills (8 February 1902 – 8 May 1903)

- Sir Henri Elzéar Taschereau (as Chief Justice 21 November 1902 – 2 May 1906; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister Mackenzie, 7 October 1878)

- John Douglas Armour (21 November 1902 – 11 July 1903)

- Wallace Nesbitt (16 May 1903 – 4 October 1905)

- Albert Clements Killam (8 August 1903 – 6 February 1905)

- John Idington (10 February 1905 – 31 March 1927)

- James Maclennan (5 October 1905 – 13 February 1909)

- Sir Charles Fitzpatrick (as Chief Justice, 4 June 1906 – 21 November 1918)

- Sir Lyman Poore Duff (27 September 1906 – 2 January 1944)

- Francis Alexander Anglin (23 February 1909 – 28 February 1933)

- Louis-Philippe Brodeur (11 August 1911 – 10 October 1923)

In popular culture

- Wilfrid Laurier appears as the leader of the Canadian civilization in the 4X video game Sid Meier's Civilization VI.[30]

See also

References

- "By restoring Laurier's lost tenets, this century could be ours". Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Hillmer, Norman; Azzi, Steven (10 June 2011). "Canada's Best Prime Ministers". Maclean's. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "Years of service in Parliament". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- Granatstein, J. L.; Hillmer, Norman (1999). Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780006385639.

- "Wilfrid Laurier". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Biography". Dictionnaire des parlementaires du Québec de 1792 à nos jours (in French). National Assembly of Quebec.

- Pierre-Luc Bégin, Loyalisme et fanatisme: petite histoire du mouvement orangiste canadien, Québec: Éditions du Québécois, 2008.

- LaPierre, Laurier (1996). Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Romance of Canada. Stoddart. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7737-2979-7.

- "Ministers of the Crown".

- "Justin Trudeau's 'sunny ways' a nod to Sir Wilfrid Laurier". CBC News. 20 October 2015.

- "Court Circular". The Times (36891). London. 6 October 1902. p. 7.

- Library and Archives Canada. Canadian Confederation: Alberta and Saskatchewan Entered Confederation: 1905. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- Government of Yukon. Yukon Historical Timeline (1886–1906). Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "The prime minister and the newspaper boy". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "The proposed ban on black immigration to Canada. Order-in-Council P. C. 1911-1324". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 195.

- Réal Bélanger, Macdonald and Laurier Days Archived 25 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "CBC Archives".

- "Thousands Mourn Laurier. Eulogies in French and English at Funeral of Ex-Premier". The New York Times. 23 February 1919.

- Michael Duffy (22 August 2009). "Who's Who – Sir Wilfrid Laurier". firstworldwar.com. firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada – Former Prime Ministers and Their Grave Sites – The Right Honourable Sir Wilfrid Laurier". Parks Canada. Government of Canada. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Negotiating the Past: The Making of Canada's National Historic Parks and Sites: (Montreal & Kingston, 1990), C.J. Taylor, pp. 119–21.

- "Musée Laurier".

- Wilfrid Laurier House National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places.

- Wilfrid Laurier House. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- The Cord Newspaper

- "Historical Chronological List Since 1867 of Members of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada". Privy Council Office (Canada). Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "The Colonial Premiers in Edinburgh". The Times (36831). London. 28 July 1902. p. 4.

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier Day Act, 2002

- Canada is Civ 6’s latest arrival, and they’re too nice to declare surprise wars. PCGamesN. Retrieved December 17 2020.

Further reading

- Armstrong, Elizabeth H. The Crisis of Quebec, 1914–1918 (1937)

- Avery, Donald, and Peter Neary. "Laurier, Borden and a White British Columbia." Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'etudes canadiennes 12.4 (1977): 24.

- Bélanger, Réal (1998). "Laurier, Sir Wilfrid". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XIV (1911–1920) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Bélanger, Réal. "Laurier, Sir Wilfrid," Dictionary of Canadian Biography vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–. Retrieved 6 November 2015, online

- Brown, Craig, and Ramsay Cook, Canada: 1896–1921 A Nation Transformed (1983), standard history

- Cook, Ramsay. "Dafoe, Laurier, and the Formation of Union Government." Canadian Historical Review 42#3 (1961) pp: 185–208.

- Dafoe, J. W. Laurier: A Study in Canadian Politics (1922) online

- Dutil, Patrice, and David MacKenzie, Canada, 1911: The Decisive Election that Shaped the Country (2011) ISBN 1554889472

- Granatstein, J.L. and Norman Hillmer, Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders. pp. 46–60. (1999). ISBN 0-00-200027-X.

- LaPierre, Laurier. Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Romance of Canada – (1996). ISBN 0-7737-2979-8

- Neatby, H. Blair. Laurier and a Liberal Quebec: A Study in Political Management (1973) online

- Neatby, H. Blair. "Laurier and imperialism." Report of the Annual Meeting. Vol. 34. No. 1. The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada, 1955. online

- Robertson, Barbara. Wilfrid Laurier: The Great Conciliator (1971)

- Schull, Joseph. Laurier. The First Canadian (1965); biography

- Skelton, Oscar Douglas. Life and Letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier 2v (1921); the standard biography v. 2 online free

- Skelton, Oscar Douglas. The Day of Sir Wilfrid Laurier A Chronicle of our own Times (1916), short popular survey online free

- Stewart, Gordon T. "Political Patronage under Macdonald and Laurier 1878–1911." American Review of Canadian Studies 10#1 (1980): 3–26.

- Stewart, Heather Grace. Sir Wilfrid Laurier: the weakling who stood his ground (2006) ISBN 0-9736406-3-4; for children

- Waite, Peter Busby, Canada, 1874–1896: Arduous Destiny (1971), standard history

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wilfrid Laurier. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Wilfrid Laurier |

- Works by or about Wilfrid Laurier at Internet Archive

- Wilfrid Laurier – Parliament of Canada biography

- Wilfrid Laurier fonds at Library and Archives Canada.

- Wilfrid Laurier on the platform; collection of the principal speeches made in Parliament or before the people, since his entry into active politics in 1871; by Wilfrid Laurier at archive.org

- Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier vol 1. at archive.org

- Life and letters of Sir Wilfrid Laurier vol 2. at archive.org

- Photograph: Wilfrid Laurier, 1890 – McCord Museum

- Photograph: Sir Wilfrid Laurier, c. 1900 – McCord Museum

- Photograph: Wilfrid Laurier, 1906 – McCord Museum

- Newspaper clippings about Wilfrid Laurier in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW