Umayyad campaigns in India

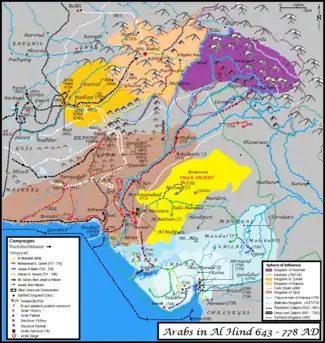

In the first half of the 8th century CE, a series of battles took place between the Umayyad Caliphate and the Indian kingdoms to the east of the Indus river.[1][lower-alpha 1]

| Umayyad campaigns in India | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Early Muslim conquests and Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent | |||||||||

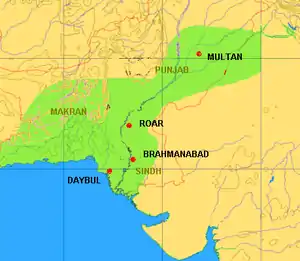

Sindh and neighbouring kingdoms | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Pratihara dynasty Chalukya dynasty Karkota Empire Maitraka dynasty |

Caliphate of Cordoba Emirate of Tunis | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Subsequent to the Arab conquest of Sindh in present-day Pakistan in 712 CE, Arab armies engaged kingdoms further east of the Indus. Between 724 and 810 CE, a series of battles took place between the Arabs and King Nagabhata I of the Pratihara dynasty, King Vikramaditya II of the Chalukya dynasty, and other small Indian kingdoms. In the north, Nagabhata of the Pratihara Dynasty defeated a major Arab expedition in Malwa.[2] From the South, Vikramaditya II sent his general Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin, who defeated the Arabs in Gujarat.[3] Later in 776 CE, a naval expedition by the Arabs was defeated by the Saindhava naval fleet under Agguka I.[4][5]

The Arab defeats led to an end of their eastward expansion, and later manifested in the overthrow of Arab rulers in Sindh itself and the establishment of indigenous Muslim Rajput dynasties (Soomras and Sammas) there.[6]

Background

After the reign of Emperor Harshavardhana, by the early 8th century, North India was divided into several kingdoms, small and large. The Northwest was controlled by the Kashmir-based Karkota dynasty, and the Hindu Shahis based in Kabul. Kanauj, the de facto capital of North India was held by Yashovarman, Northeast India was held by the Pala dynasty, and South India by the powerful Chalukyas. Western India was dominated by the Rai dynasty of Sindh, and several kingdoms of Gurjara clans, based at Bhinmal (Bhillamala), Mandor, Nandol-Broach (Nandipuri-Bharuch) and Ujjain. The last of these clans, who called themselves Pratiharas were to be the eventually dominating force. Altogether, the combined region of southern Rajasthan and northern Gujarat was called Gurjaradesa (Gurjara country), before it got renamed to Rajputana in later medieval times. The Kathiawar peninsula (Saurashtra) was controlled by several small kingdoms, such as Saindhavas, and dominated by Maitrakas at Vallabhi.[7]

The third wave of military expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate lasted from 692 to 718 CE. The reign of Al-Walid I (705–715 CE) saw the most dramatic Marwanid Umayyad conquests. In a period of barely ten years, North Africa, Spain, Transoxiana, and Sindh were subdued and colonised.[8] Sindh, controlled by King Raja Dahir of the Rai dynasty, was captured by the Umayyad general Muhammad bin Qasim.[9] Sindh, now a second-level province of the Caliphate (iqlim) with its capital at Al Mansura, was a suitable base for excursions into India. But, after bin Qasim's departure most of his captured territories were recaptured by Indian kings.[10]

During the reign of Yazid II (720 to 724 CE), the fourth expansion was launched to all the warring frontiers, including India. The campaign lasted from 720 to 740 CE. During Yazid's times, there was no significant check to the Arab expansion. However, the advent of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 691–743 CE), the 10th Umayyad Caliph, saw a turn in the fortune of the Umayyads which resulted in eventual defeat on all the fronts and a complete halt of Arab expansionism. The hiatus from 740 to 750 CE due to military exhaustion, also saw the advent of the third of a series of civil wars, which resulted in the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate.[11]

Campaign by Muhammad bin Qasim (712–715)

After conquering Brahmanabad in Sindh, Bin Qasim co-opted the local Brahman elite, whom he held in esteem, re-appointing them to posts held under the Brahman dynasty and offering honours and awards to their religious leaders and scholars.[12] This arrangement with local Brahman elites resulted in the continued persecution of Jatts, with Bin Qasim confirming the existing Brahman regulation forbidding them from wearing anything but coarse clothing and requiring them to always walk barefoot accompanied by dogs.[13]

Following his success in Sindh, Muhammad bin Qasim wrote to `the kings of Hind' calling upon them to surrender and accept the faith of Islam.[14] He dispatched a force against al-Baylaman (Bhinmal), which is said to have offered submission. The Mid people of Surast (Maitrakas of Vallabhi) also made peace.[15] Bin Qasim then sent a cavalry of 10,000 to Kanauj, along with a decree from the Caliph. He himself went with an army to the prevailing frontier of Kashmir called panj-māhīyāt (in west Punjab).[16] Nothing is known of the Kanauj expedition. The frontier of Kashmir might be what is referred to as al-Kiraj in later records (Kira kingdom in Kangra Valley, Himachal Pradesh[17]), which was apparently subdued.[18]

Bin Qasim destroyed the temples and "idolatrous" artwork. He attempted to establish Sharia law in the conquered regions and during these campaigns, the native population of the region suffered religious persecution, selective killings of males, rapes, and forced marriages of women.[19]

Bin Qasim was recalled in 715 CE and died en route. Al-Baladhuri writes that, upon his departure, the kings of al-Hind had come back to their kingdoms. The period of Caliph Umar II (r. 717–720) was relatively peaceful. Umar invited the kings of "al-Hind" to convert to Islam and become his subjects, in return for which they would continue to remain kings. Hullishah of Sindh and other kings accepted the offer and adopted Arab names.[20] During the caliphates of Yazid II (r. 720–724) and Hisham (r. 724–743), the expansion policy was resumed. Junayd ibn Abd ar-Rahman al-Murri (or Al Junayd) was appointed the governor of Sindh in 723 CE.

Campaign by Al Junayd (723–726)

After subduing Sindh, Junayd sent campaigns to various parts of India. The justification was that these parts had previously paid tribute to Bin Qasim but then stopped. The first target was al-Kiraj (possibly Kangra valley), whose conquest effectively put an end to the kingdom. A large campaign was carried out in Rajasthan which included Mermad (Maru-Mada, in Jaisalmer, north Jodhpur), al-Baylaman (Bhillamala or Bhinmal) and Jurz (Gurjara country—southern Rajasthan and northern Gujarat). Another force was sent against Uzayn (Ujjain), which made incursions into its country (Avanti) and some parts of it were destroyed (the city of Baharimad, unidentified). Ujjain itself may not have been conquered. A separate force was also sent against al-Malibah (Malwa, to the east of Ujjain[21]), but the outcome is not recorded.[22]

Towards the North, Umayyads attempted to expand into Punjab but were defeated by Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir.[23] Another force was dispatched south. It subdued Qassa (Kutch), al-Mandal (perhaps Okha), Dahnaj (unidentified), Surast (Saurashtra) and Barus or Barwas (Bharuch).[22]

The kingdoms weakened or destroyed included the Bhattis of Jaisalmer, the Gurjaras of Bhinmal, the Mauryas of Chittor, the Guhilots of Mewar, the Kacchelas of Kutch, the Maitrakas of Saurashtra and Gurjaras of Nandipuri. Altogether, Al-Junayd might have conquered all of Gujarat, a large part of Rajasthan, and some parts of Madhya Pradesh. Blankinship states that this was a full-scale invasion carried out with the intent of founding a new province of the Caliphate.[24]

In 726 CE, the Caliphate replaced Al-Junayd by Tamim ibn Zaid al-Utbi as the governor of Sindh. During the next few years, all of the gains made by Junayd were lost. The Arab records do not explain why, except to state that the Caliphate troops, drawn from distant lands such as Syria and Yemen, abandoned their posts in India and refused to go back. Blankinship admits the possibility that the Indians must have revolted, but thinks it more likely that the problems were internal to the Arab forces.[25]

Governor Tamim is said to have fled Sindh and died en route. The Caliphate appointed al-Hakam ibn Awana al-Kalbi (Al-Hakam) in 731 who governed till 740.

Al-Hakam and Indian resistance (731–740)

Al-Hakam restored order to Sindh and Kutch and built secure fortifications at Al-Mahfuzah and Al-Mansur. He then proceeded to retake Indian kingdoms previously conquered by Al-Junayd. The Arab sources are silent on the details of the campaigns. However, several Indian sources record victories over the Arab forces.[26]

The Gurjara king of Nandipuri, Jayabhata IV, documented, in an inscription dated to 736 CE, that he went to the aid of the king of Vallabhi and inflicted a crushing defeat on a Tājika (Arab) army. The Arabs then overran the kingdom of Jayabhata himself and proceeded on to Navsari in southern Gujarat.[27] The Arab intention might have been to make inroads into South India. However, to the south of the Mahi River lay the powerful Chalukyan empire. The Chalukyan viceroy at Navsari, Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin, decisively defeated the invading Arab forces as documented in a Navsari grant of 739 CE. The Tājika (Arab) army defeated was, according to the grant, one that had attacked "Kacchella, Saindhava, Saurashtra, Cavotaka, Maurya and Gurjara" kings. Pulakeshin subsequently received the titles "Solid Pillar of Deccan" (Dakshināpatha-sādhāra) and the "Repeller of the Unrepellable" (Anivartaka-nivartayitr). The Rashtrakuta prince Dantidurga, who was subsidiary to Chalukyas at this time, also played an important role in the battle.[28]

The kingdoms recorded in the Navsari grant are interpreted as follows: Kacchelas were the people of Kutch. The Saindhavas are thought to have been emigrants from Sindh, who presumably moved to Kathiawar after the Arab occupation of Sindh in 712 CE. Settling down in the northern tip of Kathiawar, they had a ruler by the name of Pushyadeva. The Cavotakas (also called Capotaka or Capa) were also associated with Kathiawar, with their capital at Anahilapataka. Saurashtra is south Kathiawar. The Mauryas and Gurjaras are open to interpretation. Blankinship takes them to be the Mauryas of Chittor and Gurjaras of Bhinmal whereas Baij Nath Puri takes them to be a subsidiary line of Mauryas based in Vallabhi and the Gurjaras of Bharuch under Jayabhata IV. In Puri's interpretation, this invasion of the Arab forces was limited to the southern parts of modern Gujarat with several small kingdoms, which was halted by the Chalukyan empire.[29]

Indications are that Al-Hakam was overstretched. An appeal for reinforcements from the Caliphate in 737 is recorded, with 600 men being sent, a surprisingly small contingent. Even this force was absorbed in its passage through Iraq for quelling a local rebellion.[30] The defeat at the hands of Chalukyas is believed to have been a blow to the Arab forces with large costs in men and arms.[30]

The weakened Arab forces were driven out by the subsidiaries of the erstwhile kings. The Guhilot prince Bappa Rawal (r. 734–753) drove out the Arabs who had put an end to the Maurya dynasty at Chittor.[31] A Jain prabandha mentions a king Nahada, who is said to have been the first ruler of his family at Jalore, near Bhinmal, and who came into conflict with a Muslim ruler whom he defeated.[32] Nahada is identified with Nagabhata I (r. 730–760), the founder of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, which is believed to have started from the Jalore-Bhinmal area and spread to Avanti at Ujjain.[33] The Gwalior inscription of the king Bhoja I, says that Nagabhata, the founder of the dynasty, defeated a powerful army of Valacha Mlecchas (foreigners called "Baluchs"[34]) around 738 CE.[35] Even though many historians believe that Nagabhata repulsed Arab forces at Ujjain.

Baij Nath Puri states that the Arab campaigns to the east of Indus proved ineffective. However, they had the unintended effect of integrating the Indian kingdoms in Rajasthan and Gujarat. The Chalukyas extended their empire to the north after fighting off the Arabs successfully. Nagabhata I secured a firm position and laid the foundation for a new dynasty, which would rise to become the principal deterrent against Arab expansion.[36] Blankinship also notes that Hakam's campaigns caused the creation of larger, more powerful kingdoms, which was inimical to the caliphate's interests.[37] Al-Hakam died in battle in 740 CE while fighting the Meds of north Saurashtra (Maitrakas, probably under the control of Chalukyas at this time).[38]

Aftermath

Following Hakam's death, the Muslim presence had effectively ended in the Indian subcontinent excluding Sindh. Al-Hakam's successor 'Amr bin Muhammad bin al-Qasim al-Thaqafi (740-43) didn't have the opportunity to undertake any offensive. The Sindhis revolted perhaps with the help of Indian kingdoms, elected a king and besieged 'Amr in the capital al-Mansura. He wrote to Yusub bin Umar, governor of Iraq, for assistance and was provided with 4,000 men to subdue the revolt which he was able to do. The next governor is said to have undertaken eighteen campaigns. If so, they were probably insignificant because the only source that reports about them gives no details and the Muslims never expanded beyond Sindh again.[39]

The death of Al-Hakam effectively ended the Arab presence to the east of Sindh. In the following years, the Arabs were preoccupied with controlling Sindh. They made occasional raids to the seaports of Kathiawar to protect their trading routes but did not venture inland into Indian kingdoms. Dantidurga, the Rashtrakuta chief of Berar turned against his Chalukya overlords in 753 and became independent. The Gurjara-Pratiharas immediately to his north became his foes and the Arabs became his allies, due to the geographic logic as well as the economic interests of sea trade. The Pratiharas extended their influence throughout Gujarat and Rajasthan almost to the edge of the Indus river, but their push to become the central power of north India was repeatedly thwarted by the Rashtrakutas. This uneasy balance of power between the three powers lasted till the end of the caliphate.

Later in 776 CE, a naval expedition by the Arabs was defeated by the Saindhava naval fleet under Agguka I.[4][5]

List of major battles

The table below lists some of the major military conflicts during the Arab expeditions in Gujarat and Rajasthan.[40]

| Arab | Indian |

(Colour legend for victor)

| Year | Aggressor | Location | Commander | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 713 | Arab | Multan | Muhammad ibn Qasim | Arab conquest of urban Sindh completed[40] |

| 715 | Indian | Alor | Hullishah, al-Muhallab | Indian army retakes major city from Arabs.[40] |

| 715 | Indian | Mehran | Hullishah, al-Muhallab | Arabs stall the Indian counter-offensive[40] |

| 718 | Indian | Brahmanabadh | Hullishah, al-Muhallab | Indian attacks resume[40] |

| 721 | Arab | Brahmanabadh | al-Muhallab, Hullishah | Hullishah becomes a Muslim, likely due to military reversals.[40] |

| 724–740 | Arab | Uzain, Mirmad, Dahnaj, others | Junayd of Sindh | Raiding India as part of Umayyad policy in India.[40] |

| 725 | Arab | Avanti | Junayd, Nagabhata I | Defeat of large Arab expedition against Avanti.[40][41] |

| 735-36 | Arab | Vallabhi, Nandipuri, Bharuch | Junayd, Pushyadeva, Siladitya IV, Jayabhata IV | Maitraka capital sacked in Arab raid. Arabs defeated Kachchelas (of Kutch), Saindhavas, Surastra (Maitrakas), Chavotkata (Chavdas), Mauryas and Gurjaras of Lata.[40][42][43] |

| 738-39 | India | Navsari | Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin | Arabs were defeated by Chalukya forces.[43] |

| 740 | Arab | Chittor | Maurya of Chittor | Indians repulse an Arab siege.[40][44] |

| 743? | Arab | al-Bailaman, al-Jurz | Junayd | Annexed by Arabs.[40][45] |

| 759 | Arab | Barda hills, Porbandar | Krishnaraja I, Amarubin Jamal | Arab naval attack defeated by Saindhava fleet.[46] |

| 776–778 | Arab | Saurashtra | Agguka I, Caliph Al-Mahdi | Arab amphibious assault annihilated.[40][47][4][5] |

| 780–787 | Arab | Fort Tharra, Bagar, Bhaqmbur | Haji Abu Turab | Vigorous Arab offensive captures several important Indian outposts.[40][48] |

| 800–810 | Indian | Sindh border | Nagabhata II, Caliph Al-Amin | Several Arab outposts fall to Pratihara incursions.[40][49] |

| 820–830 | Arab | Fort Sindan | al-Fadl ibn Mahan | Sindan captured, but Indian riots make pacification of the region impossible.[40] |

| 839 | Indian | Fort Sindan | Mihira Bhoja | Indians expel Arab garrison.[40] |

| 845 | Indian | Yavana | Dharmpala? | Arab principality becomes vassal of Pratiharas.[40] |

| 845–860 | Indian | Pratihara-Sindh | Mihira Bhoja | Uneasy truce between Sindh and Rajputana.[40] |

| 860 | Indian | Rajputana-Sindh | Kokkalla I | Kalachuri raids into Sindh to finance war with Pratihara kingdom[40] |

See also

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

- List of early Hindu Muslim military conflicts in the Indian subcontinent

Notes

- "India" in this page refers to the territory of present day India.

References

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Barnsley, Great Britain: Pen & Sword Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-84884-612-8.

- Sandhu, Gurcharn Singh (2000). A Military History of Ancient India. Vision Books. p. 402.

- Majumdar 1977, p. 279.

- Kumar, Amit (2012). "Maritime History of India: An Overview". Maritime Affairs:Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India. 8 (1): 93–115. doi:10.1080/09733159.2012.690562. S2CID 108648910.

In 776 AD, Arabs tried to invade Sind again but were defeated by the Saindhava naval fleet. A Saindhava inscription provides information about these naval actions.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1 January 1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 343–344. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Siddiqui, Habibullah. "The Soomras of Sindh: their origin, main characteristics and rule – an overview (general survey) (1025 – 1351 AD)" (PDF). Literary Conference on Soomra Period in Sindh.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 110–111; Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 266

- Blankinship 1994, p. 29.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 30.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 19, 41.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 19.

- Moosvi, Shireen. "The Medieval State and Caste." Social Scientist 39, no. 7/8 (2011): 3-8. Accessed July 12, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41289417.

- Moosvi, Shireen. "The Medieval State and Caste." Social Scientist 39, no. 7/8 (2011): 3-8. Accessed July 12, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41289417.

- Wink 2002, p. 206: "And Al-Qasim wrote letters `to the kings of Hind (bi-mulūk-i-hind) calling upon them all to surrender and accept the faith of Islam (bi-muṭāwa`at-o-islām)'. Ten thousand-strong cavalries were sent to Kannauj from Multan, with a decree of the caliph, inviting the people `to share in the blessings of Islam, to submit and do homage and pay tribute'."

- Al-Baladhuri 1924, p. 223.

- Wink 2002, p. 206.

- Tripathi 1989, p. 218.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 132.

- B. S. Ahloowalia (2009). Invasion of the Genes Genetic Heritage of India. Strategic Book Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-1608606917.

- Wink 2002, p. 207.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1972). Malwa through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidas. p. 10. ISBN 9788120808249.

- Bhandarkar 1929, pp. 29–30; Wink 2002, p. 208; Blankinship 1994, pp. 132–133

- Hasan, Mohibbul (1959). Kashmir Under the Sultans. Delhi: Aakar Books. p. 30.

In the reign of Caliph Hisham (724–43) the Arabs of Sindh under their energetic and ambitious governor Junaid again threatened Kashmir. But Lalitadaitya (724–60), who was the ruler of Kashmir at this time, defeated him and overran his kingdom. His victory was, however, not decisive for the Arab aggression did not cease. That is why the Kashmiri ruler, pressed by them from the south and by the Turkish tribes and the Tibetans from the north, had to invoke the help of the Chinese emperor and to place himself under his protection. But, although he did not receive any aid, he was able to stem the tide of Arab advance by his own efforts.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 133-134.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 147–148.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 187.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 187; Puri 1986, p. 44; Chattopadhyaya 1998, p. 32

- Blankinship 1994, p. 186; Bhandarkar 1929, pp. 29–30; Majumdar 1977, pp. 266–267; Puri 1986, p. 45; Wink 2002, p. 208; Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, p. 348; Chattopadhyaya 1998, pp. 33–34

- Blankinship 1994, p. 187; Puri 1986, pp. 45–46

- Blankinship 1994, p. 188.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 188; Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, pp. 336–337

- Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 204.

- Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 187.

- Bhandarkar 1929, p. 30.

- Bhandarkar 1929, pp. 30–31; Rāya 1939, p. 125; Majumdar 1977, p. 267; Puri 1986, p. 46; Wink 2002, p. 208

- Puri 1986, p. 46.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 189–190.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 189.

- Khalid Yahya Blankinship. End of the Jihad State, The: The Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. SUNY Press. pp. 203–204. ISBN 9780791496831.

- Richards, J.F. (1974). "The Islamic frontier in the east: Expansion into South Asia". Journal of South Asian Studies. 4 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1080/00856407408730690.

- Hem Chandra Ray 1931, pp. 9–10.

- Hem Chandra Ray 1931, p. 10.

- Virji 1955, p. 94–96.

- Vaidya 1921, p. 73.

- Hem Chandra Ray 1931, p. 9.

- Virji 1955, p. 97–100.

- Majumdar 1955, Vol. IV, pp. 98–99.

- Elliot 1869, Vol. 1, p. 446.

- Majumdar 1955, Vol. IV, pp. 24–25, 128.

Bibliography

- Al-Baladhuri, Abul Abbas Ahmad ibn-Jabir (1924). Kitab Futuh Al-Buldan [The Origins of Islamic State]. 2. Translated by Francis Clark Murgotten. Columbia University.

- Bhandarkar, D. R. (1929). "Indian Studies No. I: Slow Progress of Islam Power in Ancient India". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 10 (1/2): 25–44. JSTOR 41682407.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Chattopadhyaya, B. D. (1998), Representing the Other? Sanskrit Sources and the Muslims, New Delhi: Manohar, ISBN 978-8173042522

- Elliot, Henry Miers (1869). History of India, as told by its own historians. London.

- Majumdar, R. C., ed. (1955). History and Culture of Indian People. Bombay.

- Majumdar, R. C. (1977). Ancient India (Eighth ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- Puri, Baij Nath (1986). The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Ray, Hem Chandra (1973) [first published 1931]. The Dynastic History of Northern India, I. Early Medieval Period. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Rāya, Panchānana (1939). A historical review of Hindu India: 300 B. C. to 1200 A. D. I. M. H. Press.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilisation. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Sharma, Sanjay (2006). "Negotiating Identity and Status Legitimation and Patronage under the Gurjara-Pratīhāras of Kanauj". Studies in History. 22 (22): 181–220. doi:10.1177/025764300602200202. S2CID 144128358.

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1989), History of Kanauj: To the Moslem Conquest, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0404-3

- Vaidya, C. V. (2013) [first published 1921]. History of Medieval Hindu India. HardPress Publishing. ISBN 978-1313363297.

- Virji, Krishnakumari Jethabhai (1955). Ancient history of Saurashtra: being a study of the Maitrakas of Valabhi V to VIII centuries A. D. Indian History and Culture Series. Konkan Institute of Arts and Sciences.

- Wink, André (2002) [first published 1996], Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World (Third ed.), Brill, ISBN 978-0391041738

Further reading

- Atherton, Cynthia Packert (1997). The Sculpture of Early Medieval Rajasthan. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004107892.

- Bose, Mainak Kumar (1988). Late classical India. Calcutta: A. Mukherjee & Co. OL 1830998M.

- O'Brien, Anthony Gordon (1996). The Ancient Chronology of Thar: The Bhattika, Laulika and Sindh Eras. Oxford University Press India. ISBN 978-1582559308.