Rajasthan

Rajasthan (/ˈrɑːdʒəstæn/ Hindustani pronunciation: [raːdʒəsˈtʰaːn] (![]() listen); literally, "Land of Kings")[8] is a state in northern India.[9][10][11] The state covers an area of 342,239 square kilometres (132,139 sq mi) or 10.4 percent of the total geographical area of India. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. Rajasthan is located on the northwestern side of India, where it comprises most of the wide and inhospitable Thar Desert (also known as the "Great Indian Desert") and shares a border with the Pakistani provinces of Punjab to the northwest and Sindh to the west, along the Sutlej-Indus river valley. It is bordered by five other Indian states: Punjab to the north; Haryana and Uttar Pradesh to the northeast; Madhya Pradesh to the southeast; and Gujarat to the southwest. Its geographical location is 23.3 to 30.12 North latitude and 69.30 to 78.17 East longitude, with the Tropic of Cancer passing through southernmost tip of the state.

listen); literally, "Land of Kings")[8] is a state in northern India.[9][10][11] The state covers an area of 342,239 square kilometres (132,139 sq mi) or 10.4 percent of the total geographical area of India. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. Rajasthan is located on the northwestern side of India, where it comprises most of the wide and inhospitable Thar Desert (also known as the "Great Indian Desert") and shares a border with the Pakistani provinces of Punjab to the northwest and Sindh to the west, along the Sutlej-Indus river valley. It is bordered by five other Indian states: Punjab to the north; Haryana and Uttar Pradesh to the northeast; Madhya Pradesh to the southeast; and Gujarat to the southwest. Its geographical location is 23.3 to 30.12 North latitude and 69.30 to 78.17 East longitude, with the Tropic of Cancer passing through southernmost tip of the state.

Major features include the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilisation at Kalibangan and Balathal, the Dilwara Temples, a Jain pilgrimage site at Rajasthan's only hill station, Mount Abu, in the ancient Aravalli mountain range and in eastern Rajasthan, the Keoladeo National Park of Bharatpur, a World Heritage Site[12] known for its bird life. Rajasthan is also home to three national tiger reserves, the Ranthambore National Park in Sawai Madhopur, Sariska Tiger Reserve in Alwar and Mukundra Hills Tiger Reserve in Kota.

The state was formed on 30 March 1949 when Rajputana – the name adopted by the British Raj for its dependencies in the region[13] – was merged into the Dominion of India. Its capital and largest city is Jaipur. Other important cities are Jodhpur, Kota, Bikaner, Ajmer, Bharatpur and Udaipur. The economy of Rajasthan is the seventh-largest state economy in India with ₹10.20 lakh crore (US$140 billion) in gross domestic product and a per capita GDP of ₹118,000 (US$1,700).[3] Rajasthan ranks 29th among Indian states in human development index.[5]

Etymology

Rajasthan literally means "The Land of Kings".[8] The oldest reference to Rajasthan is found in a stone inscription dated back to 625 CE.[14] The print mention of the name "Rajasthan" appears in the 1829 publication Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India, while the earliest known record of "Rajputana" as a name for the region is in George Thomas's 1800 memoir Military Memories.[15] John Keay, in his book India: A History, stated that "Rajputana" was coined by the British in 1829, John Briggs, translating Ferishta's history of early Islamic India, used the phrase "Rajpoot (Rajput) princes" rather than "Indian princes".[16]

History

Ancient

Parts of what is now Rajasthan were partly part of the Vedic Civilisation and Indus Valley Civilization. Kalibangan, in Hanumangarh district, was a major provincial capital of the Indus Valley Civilization.[17] Another archaeological excavation at Balathal site in Udaipur district shows a settlement contemporary with the Harrapan civilisation dating back to 3000–1500 BCE.

Stone Age tools dating from 5,000 to 200,000 years were found in Bundi and Bhilwara districts of the state.[18]

Matsya Kingdom of the Vedic civilisation of India, is said to roughly corresponded to the former state of Jaipur in Rajasthan and included the whole of Alwar with portions of Bharatpur.[19][20] The capital of Matsya was at Viratanagar (modern Bairat), which is said to have been named after its founder king Virata.[21]

Bhargava[22] identifies the two districts of Jhunjhunu and Sikar and parts of Jaipur district along with Haryana districts of Mahendragarh and Rewari as part of Vedic state of Brahmavarta. Bhargava also locates the present day Sahibi River as the Vedic Drishadwati River, which along with Saraswati River formed the borders of the Vedic state of Brahmavarta.[23] Manu and Bhrigu narrated the Manusmriti to a congregation of seers in this area only. Ashrams of Vedic seers Bhrigu and his son Chayvan Rishi, for whom Chyawanprash was formulated, were near Dhosi Hill part of which lies in Dhosi village of Jhunjhunu district of Rajasthan and part lies in Mahendragarh district of Haryana.[24]

The Western Kshatrapas (405–35 BCE), the Saka rulers of the western part of India, were successors to the Indo-Scythians and were contemporaneous with the Kushans, who ruled the northern part of the Indian subcontinent. The Indo-Scythians invaded the area of Ujjain and established the Saka era (with their calendar), marking the beginning of the long-lived Saka Western Satraps state.[25]

Gurjara-Pratihara

The Gurjaras ruled for many dynasties in this part of the country, the region was known as Gurjaratra.[26] Up to the 10th century CE, almost all of North India acknowledged the supremacy of the Gurjaras, with their seat of power at Kannauj.[27]

The Gurjara Pratihar Empire acted as a barrier for Arab invaders from the 8th to the 11th century. The chief accomplishment of the Gurjara-Pratihara Empire lies in its successful resistance to foreign invasions from the west, starting in the days of Junaid. Historian R. C. Majumdar says that this was openly acknowledged by the Arab writers. He further notes that historians of India have wondered at the slow progress of Muslim invaders in India, as compared with their rapid advance in other parts of the world. Now there seems little doubt that it was the power of the Gurjara Pratihara army that effectively barred the progress of the Arabs beyond the confines of Sindh, their only conquest for nearly 300 years.[28]

Medieval and Early Modern

Traditionally the Brahmins, Rajputs, Gurjars, Jats, Meenas, Bhils, Dhankas, Rajpurohits, Charans, Sunaars, Yadavs, Bishnois, Meghwals, Sermals, Rajput Malis (Sainis) and other tribes made a great contribution in building the state of Rajasthan. All these tribes suffered great difficulties in protecting their culture and the land. Millions of them were killed trying to protect their land.

Prithviraj Chauhan defeated the invading Muhammad Ghori in the First Battle of Tarain in 1191. In 1192 CE, Muhammad Ghori decisively defeated Prithviraj at the Second Battle of Tarain. After the defeat of Chauhan in 1192 CE, a part of Rajasthan came under Muslim rulers. The principal centers of their powers were Nagaur and Ajmer. Ranthambhore was also under their suzerainty. At the beginning of the 13th century, the most prominent and powerful state of Rajasthan was Mewar. The Rajputs resisted the Muslim incursions into India, although a number of Rajput kingdoms eventually became subservient to the Delhi Sultanate.

The Rajputs put up resistance to the Islamic invasions with their warfare and chivalry for centuries. The Rana's of Mewar led other kingdoms in its resistance to outside rule. Rana Hammir Singh, defeated the Tughlaq dynasty and recovered a large portion of Rajasthan. The indomitable Rana Kumbha defeated the Sultans of Malwa, Nagaur and Gujarat and made Mewar the most powerful Rajput Kingdom in India. The ambitious Rana Sanga united the various Rajput clans and fought against the foreign powers in India. Rana Sanga defeated the Afghan Lodi Empire of Delhi and crushed the Turkic Sultanates of Malwa and Gujarat. Rana Sanga then tried to create an Indian empire but was defeated by the first Mughal Emperor Babur at Khanua. The defeat was due to betrayal by the Tomar king Silhadi of Raisen. After Rana Sangas death there was no one who could check the rapid expansion of the Mughal Empire.[29]

Hem Chandra Vikramaditya, the Hindu Emperor,[30][31] was born in the village of Machheri in Alwar District in 1501. He won 22 battles against Afghans, from Punjab to Bengal including states of Ajmer and Alwar in Rajasthan, and defeated Akbar's forces twice, first at Agra and then at Delhi in 1556 at Battle of Delhi[32] before acceding to the throne of Delhi and establishing the "Hindu Raj" in North India, albeit for a short duration, from Purana Quila in Delhi. Hem Chandra was killed in the battlefield at Second Battle of Panipat fighting against Mughals on 5 November 1556.

During Akbar's reign most of the Rajput kings accepted Mughal suzerainty, but the rulers of Mewar (Rana Udai Singh II) and Marwar (Rao Chandrasen Rathore) refused to have any form of alliance with the Mughals. To teach the Rajputs a lesson Akbar attacked Udai Singh and killed Rajput commander Jaimal of Chitor and the citizens of Mewar in large numbers. Akbar killed 20,000 – 25,000 unarmed citizens in Chittor on the grounds that they had actively helped in the resistance.[33]

Maharana Pratap took an oath to avenge the citizens of Chittor, he fought the Mughal empire till his death and liberated most of Mewar apart from Chittor itself. Maharana Pratap soon became the most celebrated warrior of Rajasthan and became famous all over India for his sporadic warfare and noble actions. According to Satish Chandra, "Rana Pratap's defiance of the mighty Mughal empire, almost alone and unaided by the other Rajput states, constitutes a glorious saga of Rajput valor and the spirit of self-sacrifice for cherished principles. Rana Pratap's methods of sporadic warfare was later elaborated further by Malik Ambar, the Deccani general, and by Shivaji".[34]

Rana Amar Singh I continued his ancestor's war against the Mughals under Jehangir, he repelled the Mughal armies at Dewar. Later an expedition was again sent under leadership of Prince Khurram, which caused much damage to life and property of Mewar. Many temples were destroyed, several villages were put on fire and women and children were captured and tortured to make Amar Singh accept surrender.[35]

During Aurangzeb's rule Rana Raj Singh I and Veer Durgadas Rathore were chief among those who defied the intolerant emperor of Delhi. They took advantage of the Aravalli hills and caused heavy damage to the Mughal armies that were trying to occupy Rajasthan.[36][37]

After Aurangzeb's death Bahadur Shah I tried to subjugate Rajasthan like his ancestors but his plan backfired when the three Rajput Raja's of Amber, Udaipur, and Jodhpur made a joint resistance to the Mughals. The Rajputs first expelled the commandants of Jodhpur and Bayana and recovered Amer by a night attack. They next killed Sayyid Hussain Khan Barha, the commandant of Mewat and many other Mughal officers. Bahadur Shah I, then in the Deccan was forced to patch up a truce with the Rajput Rajas.[38] The Jats, under Suraj Mal, overran the Mughal garrison at Agra and plundered the city taking with them the two great silver doors of the entrance of the famous Taj Mahal which were then melted down by Suraj Mal in 1763.[39]

Over the years, the Mughals began to have internal disputes which greatly distracted them at times. The Mughal Empire continued to weaken, and with the decline of the Mughal Empire in the late 18th century, Rajputana came under the influence of the Marathas. The Maratha Empire, which had replaced the Mughal Empire as the overlord of the subcontinent, was finally replaced by the British Empire in 1818.[40]

In the 19th century, the Rajput kingdoms were exhausted, they had been drained financially and in manpower after continuous wars and due to heavy tributes exacted by the Maratha Empire. To save their kingdoms from instability, rebellions and banditry the Rajput kings concluded treaties with the British in the early 19th century, accepting British suzerainty and control over their external affairs in return for internal autonomy.[41]

Rana Kumbha was the vanguard of the fifteenth century Rajput resurgence.[42]

Rana Kumbha was the vanguard of the fifteenth century Rajput resurgence.[42] The emperor Hemu, who rose from obscurity and briefly established himself as ruler in northern India, from Punjab to Bengal, in defiance of the warring Sur and Mughal Empires.

The emperor Hemu, who rose from obscurity and briefly established himself as ruler in northern India, from Punjab to Bengal, in defiance of the warring Sur and Mughal Empires. Maharana Udai Singh II founded Udaipur, which became the new capital of the Mewar kingdom after Chittor Fort was conquered by the Mughal emperor Akbar.

Maharana Udai Singh II founded Udaipur, which became the new capital of the Mewar kingdom after Chittor Fort was conquered by the Mughal emperor Akbar. Maharana Pratap Singh, sixteenth-century Rajput ruler of Mewar, known for his defense of his realm against Mughal invasion.

Maharana Pratap Singh, sixteenth-century Rajput ruler of Mewar, known for his defense of his realm against Mughal invasion.

Modern

Modern Rajasthan includes most of Rajputana, which comprises the erstwhile nineteen princely states, two chiefships, and the British district of Ajmer-Merwara.[44] Jaisalmer, Marwar (Jodhpur), Bikaner, Mewar (Chittorgarh), Alwar and Dhundhar (Jaipur) were some of the main Rajput princely states. Bharatpur and Dholpur were Jat princely states whereas Tonk was a princely state under Pathans.[45]

Geography

The geographic features of Rajasthan are the Thar Desert and the Aravalli Range, which runs through the state from southwest to northeast, almost from one end to the other, for more than 850 kilometres (530 mi). Mount Abu lies at the southwestern end of the range, separated from the main ranges by the West Banas River, although a series of broken ridges continues into Haryana in the direction of Delhi where it can be seen as outcrops in the form of the Raisina Hill and the ridges farther north. About three-fifths of Rajasthan lies northwest of the Aravallis, leaving two-fifths on the east and south direction.

The Aravalli Range runs across the state from the southwest peak Guru Shikhar (Mount Abu), which is 1,722 metres (5,650 ft) in height, to Khetri in the northeast. This range divides the state into 60% in the northwest of the range and 40% in the southeast. The northwest tract is sandy and unproductive with little water but improves gradually from desert land in the far west and northwest to comparatively fertile and habitable land towards the east. The area includes the Thar Desert. The south-eastern area, higher in elevation (100 to 350 m above sea level) and more fertile, has a very diversified topography. in the south lies the hilly tract of Mewar. In the southeast, a large area within the districts of Kota and Bundi forms a tableland. To the northeast of these districts is a rugged region (badlands) following the line of the Chambal River. Farther north the country levels out; the flat plains of the northeastern Bharatpur district are part of an alluvial basin. Merta City lies in the geographical center of Rajasthan.

The Aravalli Range and the lands to the east and southeast of the range are generally more fertile and better watered. This region is home to the Kathiawar-Gir dry deciduous forests ecoregion, with tropical dry broadleaf forests that include teak, Acacia, and other trees. The hilly Vagad region, home to the cities of Dungarpur, and Banswara lies in southernmost Rajasthan, on the border with Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. With the exception of Mount Abu, Vagad is the wettest region in Rajasthan, and the most heavily forested. North of Vagad lies the Mewar region, home to the cities of Udaipur and Chittaurgarh. The Hadoti region lies to the southeast, on the border with Madhya Pradesh. North of Hadoti and Mewar lies the Dhundhar region, home to the state capital of Jaipur. Mewat, the easternmost region of Rajasthan, borders Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. Eastern and southeastern Rajasthan is drained by the Banas and Chambal rivers, tributaries of the Ganges.

The northwestern portion of Rajasthan is generally sandy and dry. Most of this region is covered by the Thar Desert which extends into adjoining portions of Pakistan. The Aravalli Range does not intercept the moisture-giving southwest monsoon winds off the Arabian Sea, as it lies in a direction parallel to that of the coming monsoon winds, leaving the northwestern region in a rain shadow. The Thar Desert is thinly populated; the town of Jodhpur is the largest city in the desert and known as the gateway of the Thar desert. The desert has some major districts like Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Barmer, Bikaner, and Nagour. This area is also important in the defence point of view. Jodhpur airbase is one of the largest airbases in India, BSF and Military bases are also situated here. A single civil airport is also situated in Jodhpur.

The Northwestern thorn scrub forests lie in a band around the Thar Desert, between the desert and the Aravallis. This region receives less than 400 mm of rain annually. Temperatures can sometimes exceed 54 °C in the summer months and drop below freezing point in the winter. The Godwar, Marwar, and Shekhawati regions lie in the thorn scrub forest zone, along with the city of Jodhpur. The Luni River and its tributaries are the major river system of Godwar and Marwar regions, draining the western slopes of the Aravallis and emptying southwest into the great Rann of Kutch wetland in neighboring Gujarat. This river is saline in the lower reaches and remains potable only up to Balotara in Barmer district. The Ghaggar River, which originates in Haryana, is an intermittent stream that disappears into the sands of the Thar Desert in the northern corner of the state and is seen as a remnant of the primitive Sarasvati river.

Mount Abu is a popular hill station in Rajasthan.

Mount Abu is a popular hill station in Rajasthan. The Thar Desert near Jaisalmer.

The Thar Desert near Jaisalmer. Aerial view Udaipur and Aravali hills.

Aerial view Udaipur and Aravali hills.

Flora and fauna

| Formation day | 1 November |

| State animal | Chinkara[46] and Camel[47] |

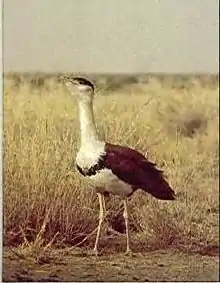

| State bird | Godavan (great Indian bustard)[46] |

| State flower | Flower – Rohida[46] |

| State Tree | Khejri[46] |

Though a large percentage of the total area is desert with little forest cover, Rajasthan has a rich and varied flora and fauna. The natural vegetation is classed as Northern Desert Thorn Forest (Champion 1936). These occur in small clumps scattered in a more or less open form. The density and size of patches increase from west to east following the increase in rainfall.

The Desert National Park in Jaisalmer is spread over an area of 3,162 square kilometres (1,221 sq mi), is an excellent example of the ecosystem of the Thar Desert and its diverse fauna. Seashells and massive fossilised tree trunks in this park record the geological history of the desert. The region is a haven for migratory and resident birds of the desert. One can see many eagles, harriers, falcons, buzzards, kestrels and vultures. Short-toed snake eagles (Circaetus gallicus), tawny eagles (Aquila rapax), spotted eagles (Aquila clanga), laggar falcons (Falco jugger) and kestrels are the commonest of these.

The Ranthambore National Park located in Sawai Madhopur,[48] one of the well known tiger reserves in the country, became a part of Project Tiger in 1973.

The Dhosi Hill located in the district of Jhunjunu, known as 'Chayvan Rishi's Ashram', where 'Chyawanprash' was formulated for the first time, has unique and rare herbs growing.

The Sariska Tiger Reserve located in Alwar district, 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Delhi and 107 kilometres (66 mi) from Jaipur, covers an area of approximately 800 square kilometres (310 sq mi). The area was declared a national park in 1979.

Tal Chhapar Sanctuary is a very small sanctuary in Sujangarh, Churu District, 210 kilometres (130 mi) from Jaipur in the Shekhawati region. This sanctuary is home to a large population of blackbuck. Desert foxes and the caracal, an apex predator, also known as the desert lynx, can also be spotted, along with birds such as the partridge, harriers, Eastern Imperial Eagle, Pale Harrier, Marsh Harrier, Short-toed Eagle, Tawny Eagle, Sparrow Hawk, Crested Lark, Demoiselle Crane, Skylarks, Green Bee-eater, Brown Dove, Black Ibis and sand grouse.[49] The Great Indian bustard, known locally as the godavan, and which is a state bird, has been classed as critically endangered since 2011.[50]

Wildlife protection

Rajasthan is also noted for its national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. There are four national parks and wildlife sanctuaries: Keladevi National Park of Bharatpur, Sariska Tiger Reserve of Alwar, Ranthambore National Park of Sawai Madhopur, and Desert National Park of Jaisalmer. A national-level institute, Arid Forest Research Institute (AFRI) an autonomous institute of the ministry of forestry is situated in Jodhpur and continuously works on desert flora and their conservation.

Ranthambore National Park is 7 km from Sawai Madhopur Railway Station. It is known worldwide for its tiger population and is considered by both wilderness lovers and photographers as one of the best places in India to spot tigers. At one point, due to poaching and negligence, tigers became extinct at Sariska, but five tigers have been relocated there.[51] Prominent among the wildlife sanctuaries are Mount Abu Sanctuary, Bhensrod Garh Sanctuary, Darrah Sanctuary, Jaisamand Sanctuary, Kumbhalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary, Jawahar Sagar sanctuary, and Sita Mata Wildlife Sanctuary.

Communication

Major ISP and telecom companies are present in Rajasthan including Airtel, Data Infosys Limited, Reliance Limited, Idea, Jio, RailTel Corporation of India, Software Technology Parks of India (STPI), Tata Telecom and Vodafone. Data Infosys was the first Internet Service Provider (ISP) to bring Internet in Rajasthan in April 1999[52] and OASIS was first private mobile telephone company. Today the largest coverage area and the clientele are with BSNL.

Government and politics

The politics of Rajasthan is dominated mainly by the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Indian National Congress.

Administrative divisions

Rajasthan is divided into 33 districts within seven divisions:

| Division | Districts |

|---|---|

| Jaipur | |

| Jodhpur | |

| Ajmer | |

| Udaipur | |

| Bikaner | |

| Kota | |

| Bharatpur |

Economy

_develpment_2016_2018_2020.png.webp)

Rajasthan's economy is primarily agricultural and pastoral. Wheat and barley are cultivated over large areas, as are pulses, sugarcane, and oilseeds. Cotton and tobacco are the state's cash crops. Rajasthan is among the largest producers of edible oils in India and the second-largest producer of oilseeds. Rajasthan is also the biggest wool-producing state in India and the main opium producer and consumer. There are mainly two crop seasons. The water for irrigation comes from wells and tanks. The Indira Gandhi Canal irrigates northwestern Rajasthan.

The main industries are mineral based, agriculture-based, and textile based. Rajasthan is the second-largest producer of polyester fiber in India. Several prominent chemical and engineering companies are located in the city of Kota, in southern Rajasthan. Rajasthan is pre-eminent in quarrying and mining in India. The Taj Mahal was built from the white marble which was mined from a town called Makrana. The state is the second-largest source of cement in India. It has rich salt deposits at Sambhar, copper mines at Khetri, Jhunjhunu, and zinc mines at Dariba, Zawar mines and Rampura Agucha (opencast) near Bhilwara. Dimensional stone mining is also undertaken in Rajasthan. Jodhpur sandstone is mostly used in monuments, important buildings, and residential buildings. This stone is termed as "Chittar Patthar". Jodhpur leads in Handicraft and Guar Gum industry. Rajasthan is also a part of the Mumbai-Delhi Industrial corridor is set to benefit economically. The State gets 39% of the DMIC, with major districts of Jaipur, Alwar, Kota and Bhilwara benefiting.[53]

Rajasthan also has reserves of low-silica limestone.[54]

Rajasthan connected 100% of its population to electricity power in 2019 (raising the rate of electricity access from 71% of population in 2015).[55] Renewable energy sector plays the most important role in the increase of generation capacities, with the main focus on solar energy. In 2020, Bhadla Solar Park was recognized as the largest cluster of photovoltaic power plants in a single region in the World, with the installed power exceeding the 2.2 GWpeak.

Agricultural production

Rajasthan is the largest producer of barley, mustard, pearl millet, coriander, fenugreek and guar in India. Rajasthan produces over 72% of guar of the world and 60% of India's barley. Rajasthan is major producer of aloe vera, amla, oranges leading producer of maize, groundnut. Rajasthan government had initiated olive cultivation with technical support from Israel. The current production of olives in the state is around 100–110 tonnes annually. Rajasthan is India's second largest producer of milk. Rajasthan has 13800 dairy co-operative societies.

Transport

Rajasthan is connected by many national highways. Most renowned being NH 8, which is India's first 4–8 lane highway.[56] Rajasthan also has an inter-city surface transport system both in terms of railways and bus network. All chief cities are connected by air, rail, and road.

Air

There are six main airports at Rajasthan – Jaipur International Airport, Jodhpur Airport, Udaipur Airport and the recently started Ajmer Airport, Bikaner Airport and Jaisalmer Airport. These airports connect Rajasthan with the major cities of India such as Delhi and Mumbai. There is another airport in Kota but is not open for commercial/civilian flights yet.

Rail

Rajasthan is connected with the main cities of India by rail.[57] Jaipur, Kota, Ajmer, Jodhpur, Bharatpur, Bikaner, Alwar, Abu Road, and Udaipur are the principal railway stations in Rajasthan. Kota City is the only electrified section served by three Rajdhani Expresses and trains to all major cities of India. There is also an international railway, the Thar Express from Jodhpur (India) to Karachi (Pakistan). However, this is not open to foreign nationals.

Road

Rajasthan is well connected to the main cities of the country including Delhi, Ahmedabad and Indore by state and national highways and served by Rajasthan State Road Transport Corporation (RSRTC)[58] and private operators. Now in March 2017, 75 percent of all national highways being built in Rajasthan according to the public works minister of Rajasthan.

.jpg.webp) Maharajah's Express dining saloon

Maharajah's Express dining saloon The Jaipur Metro is an important urban transportation link

The Jaipur Metro is an important urban transportation link

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 10,294,090 | — |

| 1911 | 10,983,509 | +0.65% |

| 1921 | 10,292,648 | −0.65% |

| 1931 | 11,747,974 | +1.33% |

| 1941 | 13,863,859 | +1.67% |

| 1951 | 15,970,774 | +1.42% |

| 1961 | 20,155,602 | +2.35% |

| 1971 | 25,765,806 | +2.49% |

| 1981 | 34,261,862 | +2.89% |

| 1991 | 44,005,990 | +2.53% |

| 2001 | 56,507,188 | +2.53% |

| 2011 | 68,548,437 | +1.95% |

| source:[59] | ||

According to the 2011 Census of India, Rajasthan has a total population of 68,548,437.[2] The native Rajasthani people make up the majority of the state's population. The state of Rajasthan is also populated by Sindhis, who came to Rajasthan from Sindh province (now in Pakistan) during the India-Pakistan separation in 1947. As for religion, Rajasthan's residents are mainly Hindus, who account for 88.49% of the population. Muslims make up 9.07%, Sikhs 1.27% and Jains 0.91% of the population.[61]

According to a report by Moneycontrol.com at the time of 2018 Rajasthan Legislative Assembly election, the Scheduled Caste (SC) population was 18%, Scheduled Tribe (ST) was 13%, Jats 12%, Gujjars and Rajputs 9% each, Brahmins and Meenas 7% each.[62] Brahmins, according to Outlook constituted 8% to 10% of the population of Rajasthan as per a 2003 report, but only 7% in a 2007 report.[63][64] According to a 2007 DNA India report, 12.5% of the state are Brahmins.[65]

| City Name | Population |

|---|---|

| Jaipur | 3,073,349 |

| Jodhpur | 1,138,300 |

| Kota | 1,001,694 |

| Bikaner | 647,804 |

| Ajmer | 551,101 |

| Udaipur | 474,531 |

| Bhilwara | 360,009 |

| Alwar | 341,422 |

| Bharatpur | 252,838 |

| Sri Ganganagar | 249,914 |

Language

Hindi is the official and the most widely spoken language in the state (90.97% of the population as per the 2001 census), followed by Bhili (4.60%), Punjabi (2.01%), and Urdu (1.17%).[11] Rajasthani is one of the main spoken languages in the state. Rajasthani and various Rajasthani dialects are counted under Hindi in the national census. In the 2001 census, standard Rajasthani had over 18 million speakers,[67] as well as millions of other speakers of Rajasthani dialects, such as Marwari.

The languages taught under the three-language formula are:[68]

First Language: Hindi

Second Language: English

Third Language: Gujarati, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi or Urdu

Culture

| Part of a series on |

| Rajasthani people |

|---|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Notable peolple |

| Rajasthan Portal |

Rajasthan is culturally rich and has artistic and cultural traditions that reflect the ancient Indian way of life. There is rich and varied folk culture from villages which are often depicted as a symbol of the state. Highly cultivated classical music and dance with its own distinct style is part of the cultural tradition of Rajasthan. The music has songs that depict day-to-day relationships and chores, often focused around fetching water from wells or ponds.[69]

Rajasthani cooking was influenced by both the war-like lifestyles of its inhabitants and the availability of ingredients in this arid region. Food that could last for several days and could be eaten without heating was preferred. The scarcity of water and fresh green vegetables have all had their effect on the cooking. It is known for its snacks like Bikaneri Bhujia. Other famous dishes include bajre ki roti (millet bread) and lahsun ki chutney (hot garlic paste), mawa kachori Mirchi Bada, Pyaaj Kachori and ghevar from Jodhpur, Alwar ka Mawa (milk cake), Kadhi kachori from Ajmer, Malpua from Pushkar, Daal kachori (Kota kachori) from Kota and rassgullas from Bikaner. Originating from the Marwar region of the state is the concept of Marwari Bhojnalaya, or vegetarian restaurants, today found in many parts of India, which offer vegetarian food popular among Marwari people.

Dal-Bati-Churma is very popular in Rajasthan. The traditional way to serve it is to first coarsely mash the Baati, and then pour pure ghee on top of it. It is served with the daal (lentils) and spicy garlic chutney. Also served with besan (gram flour) ki kadi. It is commonly served at all festivities, including religious occasions, wedding ceremonies, and birthday parties in Rajasthan.

The Ghoomar dance from Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Kalbelia of the Kalbelia tribe have gained international recognition. Folk music is a large part of the Rajasthani culture. The Manganiyar and Langa communities from Rajasthan are notable for their folk music. Kathputli, Bhopa, Chang, Teratali, Ghindr, Gair dance, Kachchhi Ghori, and Tejaji are examples of traditional Rajasthani culture. Folk songs are commonly ballads that relate heroic deeds and love stories; and religious or devotional songs known as bhajans and banis which are often accompanied by musical instruments like dholak, sitar, and sarangi are also sung.

Rajasthan is known for its traditional, colorful art. The block prints, tie and dye prints, Gota Patti (main), Bagaru prints, Sanganer prints, and Zari embroidery are major export products from Rajasthan. Handicraft items like wooden furniture and crafts, carpets, and blue pottery are commonly found here. Shopping reflects the colorful culture, Rajasthani clothes have a lot of mirror work and embroidery. A Rajasthani traditional dress for females comprises an ankle-length skirt and a short top, known as chaniya choli Mainly pure owned by traditional people. A piece of cloth is used to cover the head, both for protection from heat and maintenance of modesty. Rajasthani dresses are usually designed in bright colors like blue, yellow, and orange.

The main religious festivals are Deepawali, Holi, Gangaur, Teej, Gogaji, Shri Devnarayan Jayanti, Makar Sankranti and Janmashtami, as the main religion is Hinduism. Rajasthan's desert festival is held once a year during winter. Dressed in costumes, the people of the desert dance and sing ballads. There are fairs with snake charmers, puppeteers, acrobats, and folk performers. Camels play a role in this festival.

Education

During recent years, Rajasthan has worked on improving education. The state government has been making sustained efforts to raise the education standard.

Literacy

In recent decades the literacy rate of Rajasthan has increased significantly. In 1991, the state's literacy rate was only 38.55% (54.99% male and 20.44% female). In 2001, the literacy rate increased to 60.41% (75.70% male and 43.85% female). This was the highest leap in the percentage of literacy recorded in India (the rise in female literacy being 23%).[70] At the Census 2011, Rajasthan had a literacy rate of 67.06% (80.51% male and 52.66% female). Although Rajasthan's literacy rate is below the national average of 74.04% and although its female literacy rate is the lowest in the country, the state has been praised for its efforts and achievements in raising literacy rates.[71][72]

In rural areas of Rajasthan, the literacy rate is 76.16% for males and 45.8% for females. This has been debated across all the party level, when the governor of Rajasthan set a minimum educational qualification for the village panchayat elections.[73][74][75]

Tourism

Rajasthan attracted a total of 45.9 million domestic and 1.6 million foreign tourists in 2017, which is the tenth highest in terms of domestic visitors and fifth highest in foreign tourists.[76] The tourism industry in Rajasthan is growing effectively each year and is becoming one of the major income sources for the state government. Rajasthan is home to attractions for domestic and foreign travellers, including the forts and palaces of Jaipur, lakes of Udaipur, Temples of Rajsamand and Pali, sand dunes of Jaisalmer and Bikaner, Havelis of Mandawa and Fatehpur, Rajasthan, wildlife of Sawai Madhopur, the scenic beauty of Mount Abu, tribes of Dungarpur and Banswara, and the cattle fair of Pushkar.

Rajasthan is known for its custom culture colors, majestic forts, and palaces, folk dances and music, local festivals, local food, sand dunes, carved temples, beautiful havelis.[77] Rajasthan's Jaipur Jantar Mantar, Mehrangarh Fort and Stepwell of Jodhpur, Dilwara Temples, Chittor Fort, Lake Palace, miniature paintings in Bundi, and numerous city palaces and Havelis are part of the architectural heritage of India. Jaipur, the Pink City, is noted for the ancient houses made of a type of sandstone dominated by a pink hue. In Jodhpur, maximum houses are painted blue.[78] At Ajmer, there is white marble Bara-dari on the Anasagar lake and Soniji Ki Nasiyan. Jain Temples dot Rajasthan from north to south and east to west. Dilwara Temples of Mount Abu, Shrinathji Temple of Nathdwara, Ranakpur Jain temple dedicated to Lord Adinath in Pali District, Jain temples in the fort complexes of Chittor, Jaisalmer and Kumbhalgarh, Lodurva Jain temples, Mirpur Jain Temple of Sirohi, Sarun Mata Temple at Kotputli, Bhandasar and Karni Mata Temple of Bikaner and Mandore of Jodhpur are some of the best examples.[79] Keoladeo National Park, Ranthambore National Park, Sariska Tiger Reserve, Tal Chhapar Sanctuary, are wildlife attractions of Rajasthan. Mewar festival of Udaipur, Teej festival and Gangaur festival in Jaipur, Desert festival of Jodhpur, Brij Holi of Bharatpur, Matsya festival of Alwar, Kite festival of Jodhpur, Kolayat fair in Bikaner are some of the most popular fairs and festivals of Rajasthan.

Camel rides in Thar desert

Camel rides in Thar desert Folk dance popular in Rajasthan

Folk dance popular in Rajasthan.jpg.webp) Demoiselle cranes in Khichan near Bikaner

Demoiselle cranes in Khichan near Bikaner Hawa Mahal

Hawa Mahal Amber Fort has seen from the bank of Maotha Lake, Jaigarh Fort on the hills in the background

Amber Fort has seen from the bank of Maotha Lake, Jaigarh Fort on the hills in the background Nakki Lake, Mount Abu

Nakki Lake, Mount Abu Mehrangarh Fort

Mehrangarh Fort Dilwara Temples

Dilwara Temples.jpg.webp) Lake Palace

Lake Palace Kirti Stambha of Fort of Chittaur

Kirti Stambha of Fort of Chittaur Tiger at Ranthambore National Park

Tiger at Ranthambore National Park Jal Mahal, Jaipur

Jal Mahal, Jaipur

References

- PTI (1 September 2019). "Kalraj Mishra is new governor of Rajasthan, Arif Mohd Khan gets Kerala | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Rajasthan Profile" (PDF). Census of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "MOSPI Net State Domestic Product, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India". Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 52nd report (July 2014 to June 2015)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 34–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Census 2011 (Final Data) – Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- "Symbols of Rajasthan". Government of Rajasthan. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (2003). The Territories and States of India. Routledge. p. 208. ISBN 9781135356255. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "INTER-STATE COUNCIL SECRETARIAT – Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India". Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "North Zone Cultural Centre". www.culturenorthindia.com. Ministry of Culture, Government of India. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "World Heritage List". Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- R.K. Gupta; S.R. Bakshi (1 January 2008). Studies in Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages The Heritage Of Rajputs (Set Of 5 Vols.). Sarup & Sons. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-81-7625-841-8. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Singh, K. S. (1998). Rajasthan. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 9788171547661.

- F. K. Kapil (1990). Rajputana states, 1817–1950. Book Treasure. p. 1. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- John Keay (2001). India: a history. Grove Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

Colonel James Todd, who, as the first British official to visit Rajasthan, spent most of the 1820s exploring its political potential, formed a very different idea of "Rush boots" […] and the whole region thenceforth became, for the British, 'Rajputana'. The word even achieved a retrospective authenticity, [for,] in [his] 1829 translation of Ferishta's history of early Islamic India, John Bridge discarded the phrase 'Indian princes', as rendered in Dow's earlier version, and substituted 'Rajpoot princes'.

- "INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION Related Articles arsenical bronze writing, literature". Amazines.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Pillai, Geetha Sunil (28 February 2017), "Stone age tools dating back 200,000 years found in Rajasthan", The Times of India, archived from the original on 20 April 2019, retrieved 23 August 2018

- Chatterjee, Ramanand (1948). The Modern review (History). 84. Prabasi Press Private Ltd.

- Sita Sharma; Pragati Prakashan (1987). Krishna Leela theme in Rajasthani miniatures. p. 132.

- Rajasthan aajtak. ISBN 978-81-903622-6-9.

- Sudhir Bhargava, "Location of Brahmavarta and Drishadwati river is important to find earliest alignment of Saraswati river" Seminar, Saraswati river-a perspective, 20–22 Nov 2009, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, organized by Saraswati Nadi Shodh Sansthan, Haryana, Seminar Report: pages 114–117

- Manusmriti

- Jain, M. S. (1 January 1993). Concise History of Modern Rajasthan. Wishwa Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7328-010-8.

- "The dynastic art of the Kushans", John Rosenfield, p 130.

- R.C. Majumdar (1994). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidassr. p. 263. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Asiatic Society of Bombay (1904). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay, Volume 21. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Bombay Branch. p. 432.

Up to the tenth century almost the whole of North India, excepting Bengal, owned their supremacy at Kannauj.

- Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

- (Elliot's History of India, Vol. V)

- Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (1960). Military History of India. Orient Longmans. ISBN 9780861251551.

- Coetzee, Daniel; Eysturlid, Lee W. (21 October 2013). Philosophers of War: The Evolution of History's Greatest Military Thinkers [2 Volumes]: The Evolution of History's Greatest Military Thinkers. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-07033-4.

- Bhardwaj, K. K. "Hemu-Napoleon of Medieval India", Mittal Publications, New Delhi, p.25

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- Chandra, Satish (2000). Medieval India. New Delhi: National Council of Educational Research and Training. p. 164.

- Pant 2012, p. 129.

- Storia does Mogor By Niccolo Manucci

- Cambridge history of India pg. 304

- The Cambridge History of India, Volume 3 pg 322

- Dwivedi, Girish Chandra; Prasad, Ishwari (1989). The Jats, Their Role in the Mughal Empire. Arnold Publishers. pp. 56–61. ISBN 978-81-7031-150-8.

- Hallissey, Robert C. (1977). The Rajput Rebellion Against Aurangzeb: A Study of the Mughal Empire in Seventeenth-century India. University of Missouri Press. pp. 34–41. ISBN 978-0-8262-0222-2.

- Bhargava, Visheshwar Sarup (1966). Marwar and the Mughal Emperors (A. D. 1526-1748). Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 123–126. ISBN 9788121504003.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- R.C.Majumdar, H.C.Raychaudhury, Kalikaranjan Datta: An Advanced History of India, fourth edition, 1978, ISBN 0-333-90298-X, Page-535

- R.K. Gupta; S.R. Bakshi (1 January 2008). Studies in Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages The Heritage Of Rajputs (5 Vols.). Sarup & Sons. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-81-7625-841-8. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Lodha, Sanjay (2011). "Subregions, Identity and Nature of Political Competition in Rajasthan". In Kumar, Ashutosh (ed.). Rethinking State Politics in India: Regions within Regions. Routledge. p. 400. ISBN 978-0415597777. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

The 19 independent ruling houses were governed by different Rajput clans, Jats and Pathans. The Chauhan Rajputs ruled Bundi, Kota and Sirohi; the Gehlot Rajputs ruled Banswara, Dungarpur, Mewar, Pratapgarh and Shahpura; the Jadon Rajputs ruled Jaisalmer and Karauli; the Jhala Rajputs were the rulers of Jhalawar; the Kachhawaha Rajputs controlled Alwar, Jaipur and the Lawa Estate; and the Rathore Rajputs looked after Bikaner, Marwar, Kishangarh and the chiefship of Kushalgarh. Bharatpur and Dholpur were under Jat rule and Tonk was ruled by the Pathans.

- "States and Union Territories Symbols". Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "Now the state animal camel". Patrika Group. 1 July 2014. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- Sadhu, Ayan; Jayam, Peter Prem Chakravarthi; Qureshi, Qamar; Shekhawat, Raghuvir Singh; Sharma, Sudarshan; Jhala, Yadvendradev Vikramsinh (28 November 2017). "Demography of a small, isolated tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) population in a semi-arid region of western India". BMC Zoology. 2: 16. doi:10.1186/s40850-017-0025-y. ISSN 2056-3132.

- "Tal Chhapar Black Buck Sanctuary". Inside Indian Jungles. 29 June 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "Ardeotis Nigriceps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "A tale of two tiger reserves". The Hindu. Jaipur. 21 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "Rajasthan's first ISP". timesofindia-economictimes. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Business Opportunities". Government of Rajasthan. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Rajasthan state mines and minerals limited". Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Naimoli, Stephen; Singh, Kartikeya (October 2019). "Engaging with India's Electrification Agenda: Powering Rajasthan" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- "Rajasthan National Highways – List of Rajasthan Roads and Highway". Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Rajasthan Railways". Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "rsrtc.gov.in". Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- "Census of India". Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Handa, Aakriti (25 October 2018). "Rajasthan Assembly Polls 2018: The caste dynamics in the state and the race for reservations". Moneycontrol. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Distribution Of Brahmin Population". Outlook. 16 June 2003. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Brahmins in India". Outlook. 4 June 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Rajasthan's Brahmins now seek job quotas". DNA India. 26 June 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Language – India, States and Union Territories" (PDF). Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General. pp. 13–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Census of India: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues –2001". www.censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "51st REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. 15 July 2015. p. 44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Singh, K S (1998). Rajasthan. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-766-1.

- "Directorate of Literacy and Continuing Education: Government of Rajasthan". Rajliteracy.org. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Rajasthan literacy rate now 67.06 : Census Data | Census 2011 Indian Population". Census2011.co.in. 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Rajasthan Population 2011 – Growth rate, literacy, sex ratio in Census 2011 "2011 Updates" InfoPiper". Infopiper.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- "Rajasthan Governor fixes minimum education qualifications for Panchayat polls". The Indian Express. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Lok Sabha TV Insights: Educational Qualification and Elections". INSIGHTS. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- "Rajasthan Education". Rajshiksha. Archived from the original on 5 December 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Tourist Visited in India 2017" (PDF). tourism.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Rajasthan, Maharajaernes land - Af Kristian Bertel". Blogger. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "Why is Jodhpur Known as the Blue City?". Times of India. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Tourist Places to Visit in Rajasthan – Rajasthan Tourism". tourism.rajasthan.gov.in. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

Further reading

- Bhattacharya, Manoshi. 2008. The Royal Rajputs: Strange Tales and Stranger Truths. Rupa & Co, New Delhi.

- Gahlot, Sukhvirsingh. 1992. RAJASTHAN: Historical & Cultural. J. S. Gahlot Research Institute, Jodhpur.

- Somani, Ram Vallabh. 1993. History of Rajasthan. Jain Pustak Mandir, Jaipur.

- Tod, James & Crooke, William. 1829. Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan or the Central and Western Rajpoot States of India,. Numerous reprints, including 3 Vols. Reprint: Low Price Publications, Delhi. 1990. ISBN 81-85395-68-3 (set of 3 vols.)

- Mathur, P.C., 1995. Social and Economic Dynamics of Rajasthan Politics (Jaipur, Aaalekh)

External links

Government

General information

- Rajasthan at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Rajasthan at Curlie

Geographic data related to Rajasthan at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Rajasthan at OpenStreetMap