Tiree

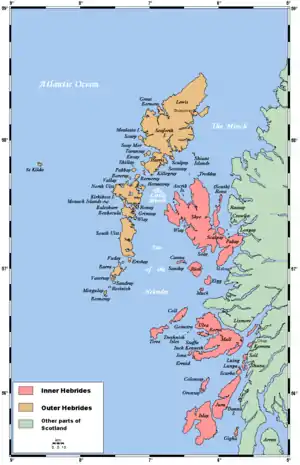

Tiree (Scottish Gaelic: Tiriodh, pronounced [ˈtʲʰiɾʲəɣ]) is the most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The low-lying island, southwest of Coll, has an area of 7,834 hectares (30 1⁄4 square miles) and a population of around 650.

| Scottish Gaelic name | Tiriodh |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ˈtʲʰiɾʲəɣ] ( |

| Old Norse name | Tyrvist |

| Meaning of name | Gaelic for 'land of corn' |

| Location | |

Tiree Tiree shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NL999458 |

| Coordinates | 56.5°N 6.88°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Mull |

| Area | 7,834 ha (30 1⁄4 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 17 [1] |

| Highest elevation | Ben Hynish 141 m (463 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 653[2] |

| Population rank | 18 [1] |

| Population density | 8.3/km2 (21/sq mi)[2][3] |

| Largest settlement | Scarinish |

| References | [3][4][5] |

The land is highly fertile, and crofting, alongside tourism, and fishing are the main sources of employment for the islanders. Tiree, along with Colonsay, enjoys a relatively high number of total hours of sunshine during the late spring and early summer compared to the average for the United Kingdom.[6] Tiree is a popular windsurfing venue; it is sometimes referred to as "Hawaii of the north".[7] In most years, the Tiree World Classic surfing event is held here.[8]

History

_(14598330869).jpg.webp)

Tiree is known for the 1st-century-AD Dùn Mòr broch, for the prehistoric carved Ringing Stone and for the birds of the Ceann a' Mhara headland.

Adomnan of Iona recorded several stories relating to St Columba and the island of Tiree.

In one story, Columba warned a monk called Berach not to sail directly from Iona to Tiree, and instead to take a different route, and the monk went against his advice and sailed directly, but along the way a huge whale came out of the sea and almost destroyed their boat. Columba gave the same warning to Baithéne mac Brénaind who replied that both he and the whale were in God's hands, and Columba told him to go, because his faith would save him. And Baithene set off for Tiree, and when the whale appeared, he raised his hands and blessed it and it went back down into the ocean.

In another story, Adomnan claimed there to be a monastery on the island of Tiree that was called Artchain. The monastery had been founded by a priest called Findchan, who was very closely attached "in a carnal way" to Áed Dub mac Suibni. Columba took issue at Aed Dub's ordination because he had previously killed a number of men, and prophesied that Aed Dub would ultimately leave the priesthood and return to his sinful life as a murderer, only to be killed violently himself.[10][11]

In another story, Adomnan claimed that Baithéne mac Brénaind asked Columba to pray for a good wind to get him to Tiree, and it was given to him, and he crossed the sea from Iona to Tiree with full sail. In another story, Columba instructed a particular monk to go the monastery on Tiree and do penance for seven years. In another story, Columba banished some demons from Iona who then went to the island of Tiree to afflict the monks there instead. Adomnan also records there being more than one monastery on Tiree in that time period, and that Baithéne mac Brénaind had been abbot of one of these monasteries.[12]

Writing in 1549, Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles wrote of "Thiridh" that it was: "ane mane laich fertile fruitful cuntrie... All inhabite and manurit with twa paroche kirkis in it, ane fresh water loch with an auld castell. Na cuntrie may be mair fertile of corn and very gude for wild fowls and for fishe, with ane gude heavin for heiland galayis".[Note 1]

In 1770, half of the island was held by fourteen farmers who had drained land for hay and pasture. Instead of exporting live cattle (which were often exhausted by the long journey to market and so fetched low prices), they began to export salt beef in barrels to get better prices. The rest of the island was let to 45 groups of tenants on co-operative joint farms: agricultural organisations probably dating from clan times. Field strips were allocated by annual ballot. Sowing and harvesting dates were decided communally. It is reported that in 1774, Tiresians were 'well-clothed and well-fed, having an abundance of corn and cattle'.

Its name derives from Tìr Iodh, 'land of the corn', from the days of the 6th century Celtic missionary and abbot St Columba (d. 597). Tiree provided the monastic community on the island of Iona, south-east of the island, with grain. A number of early monasteries once existed on Tiree itself, and several sites have stone cross-slabs from this period, e.g. St Patrick's Chapel, Ceann a' Mhara (NL 938 401) and Soroby (NL 984 416).

Skerryvore lighthouse, 12 miles (19 kilometres) south west of Tiree, was built with some difficulty between 1838 and 1844 by Alan Stevenson.

A large Royal Air Force station was built on Tiree during World War II becoming Tiree Airport in 1947.[14] There was also an RAF Chain Home radar station at Kilkenneth and an RAF Chain Home Low radar station at Beinn Hough. These were preceded by a temporary RAF Advanced Chain Home radar station at Port Mor and an RAF Chain Home Beam radar station at Barrapol. Post war there was RAF Scarinish ROTOR radar station at Beinn Ghott.

Geology

Tiree is formed largely from gneiss forming the Lewisian complex, a suite of metamorphic rocks of Archaean to early Proterozoic age. Granite of Archaean age is found locally. Igneous intrusions of dolerite, felsite, lamprophyre and diorite of Palaeozoic age are encountered in places.[15] The eastern part of the island is traversed by numerous normal faults most of which run broadly northwest–southeast. Quaternary sediments include raised beach deposits which are extensive across the island and incorporating areas of alluvium locally. There are considerable areas of blown sand in the west and behind the major bays elsewhere.[16]

Geography

The main village on Tiree is Scarinish. The island's other settlements include Hynish and Sandaig, both of which boast small museums.

The highest point on Tiree is Ben Hynish, to the south of the island, which rises to 141 metres (463 feet).

Transport

CalMac operate a ferry to Scarinish. The daily crossing from Oban on the mainland takes four hours.[17] A call is made at Arinagour on Coll and once a week the ferry crosses to Castlebay on Barra. More limited services operate in Winter.

Tiree Airport is located at Crossapol. Loganair provide daily flights to Glasgow International and Hebridean Air Services fly to Coll and Oban.[18]

Roads on Tiree, in common with many other small islands, are nearly all single-track roads. There are passing places, locally called 'pockets', where cars must wait to enable oncoming traffic to pass or overtake.

| Preceding station | Ferry | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coll | Caledonian MacBrayne Ferry |

Oban | ||

| Coll | Caledonian MacBrayne Ferry (limited service, summer only) |

Castlebay |

Climate

-GB.png.webp)

As with the rest of western Scotland, Tiree experiences a maritime climate (Cfb) with cool summers and mild winters. Despite it being on the same latitude as Labrador on the opposite side of the Atlantic Ocean, snow and frost are rare, and if they occur, short-lived. Weather data is collected at the island's airport. The lowest temperature to occur in recent years was −5.8 °C (21.6 °F) during the cold spell of December 2010.[19] The extreme maritime moderation contributes to summer temperatures that are far below even coastal locations in continental Europe on similar latitudes. Winter temperatures are similar to those of coastal southern England.

| Climate data for Tiree, 9m asl, 1981–2010, Extremes 1951– | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−7 (19) |

−7 (19) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 137.8 (5.43) |

101.3 (3.99) |

103.0 (4.06) |

72.8 (2.87) |

59.6 (2.35) |

65.0 (2.56) |

79.7 (3.14) |

106.9 (4.21) |

112.0 (4.41) |

149.5 (5.89) |

135.8 (5.35) |

131.7 (5.19) |

1,255.1 (49.41) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 20.2 | 16.2 | 18.3 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 19.6 | 19.5 | 19.4 | 194.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 39.0 | 69.9 | 111.1 | 175.2 | 238.8 | 205.5 | 174.4 | 163.3 | 128.2 | 88.4 | 46.8 | 36.0 | 1,476.6 |

| Source 1: Met Office[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute/KNMI[21] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The fertile machair lands of the island provide for good quality farming and crofting.

Tiree Community Development Trust have commissioned a 950 kW community-owned wind turbine project, the fourth such large-scale project in Scotland.[22] The first three projects were on Gigha and Westray and at Findhorn Ecovillage. The Argyll Array, an offshore wind farm development has been proposed around Skerryvore.[23]

The island is a popular destination for family holidays. Discover Tiree, established in 2002, has been providing information for visitors since that time.

Tiree is popular for windsurfing. The island hosts the Tiree Wave Classic on a regular basis[24] and was the venue for the Corona Extra PWA World Cup Finals in 2007.[25] It is visited regularly by surfing clubs, including Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Glasgow university clubs.[26] There is a radar station which tracks civil aircraft.

The island's population was 653 as recorded by the 2011 census[2] a drop of over 15% since 2001 when there were 770 usual residents.[27] During the same period Scottish island populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702.[28]

Tiree has a rich distilling history and is home to a distillery which was set up to re-establish the island's whisky heritage and, as of 2019, is producing Tyree Gin,[29] The distillery has plans to make Scotch Whisky.

Culture and media

The island is known for its vernacular architecture, including a 'blackhouse' and 'white houses', many retaining their traditional thatched roofs, as well as its unique 'pudding' or 'spotted houses' where only the mortar is painted white.

Tiree has a declining but still considerable percentage of Gaelic speakers.[30] In 2001, 368 residents (47.8%) spoke Gaelic. By 2011 the figure had decreased to 240 (38.3%), still the highest percentage of speakers in the Inner Hebrides.[31][32]

Since 2010, the island has hosted the annual Tiree Music Festival, held in the car park of the island hall 'An Talla'.[33] In 2012, when Tiree appeared in the BBC Programme Coast for a second time the actions of RAF weather forecasters, flying hazardous missions far out into the storms of the Atlantic during World War II, were discussed.

Tiree is the subject of a traditional Scottish song titled "Dark Island", which tells a tale of a ship leaving Oban and passing the "isle of my childhood", Tiree.[34] Tiree is mentioned in Enya's 1988 single "Orinoco Flow". Tiree is also referenced in the song "Western Ocean" by Skipinnish, a traditional Scottish band co-founded by local Tiresian Angus MacPhail.[35]

The Tiree Songbook is an album of songs from Na Bàird Thirisdeach, a 20th Century book collecting songs from Tiree, and new compositions about the island.[36] The album won the Community Project of the Year award at the Scots Trad Music Awards in 2017.

See also

Notes

- English translation from Lowland Scots: "a low-lying fertile fruitful country... Its entirety is inhabited and manured and there are two parish churches and a freshwater lake with an old castle. Nowhere is more fertile for corn and it is good for wild fowl and fish, with a good harbour for Highland galleys."[13]

References

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 112

- Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- Mayes, Julian; Wheeler (1997). "The Highlands and Islands of Scotland". Regional Climates of the British Isles. Dennis (Perback ed.). Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-415-13931-1. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- "Ferry To & From Tiree | Visit Tiree | CalMac". www.calmac.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- The perfect way to go island hopping in the Hebrides

- Harvie-Brown, J.A. and Buckley, T. E. (1892), A Vertebrate Fauna of Argyll and the Inner Hebrides. Pub. David Douglas., Edinburgh. Facing P. LXIV.

- Thomas Innes, The Civil and Ecclesiastical History of Scotland, Aberdeen, 1853.

- Carlos Herrero, and Elena González-Cascos, Philip Perry’s Sketch of the Ancient British History: A Critical Edition

- Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Penguin Books, 1995

- Munro, D. (1818) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland called Hybrides, by Mr. Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, who travelled through most of them in the year 1549. Miscellanea Scotica, 2. Quoted in Banks (1977) p. 190

- "RAF Tiree airfield". Control Towers. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "Tiree and Coll Scotland sheet 42 and 51W (Solid and Drift Geology)". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Onshore Geoindex". British Geological Survey. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Summer Timetables: Coll and Tiree". CalMac. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- "Summer Timetable 2012". Hebridean Air Services. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- "2010 temperature". UKMO. 2010-12-18.

- "Tiree 1981–2010 averages". UKMO. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- "Extremes for Tiree". KNMI.

- "Tiree renewable energy". Tiree Renewable Energy. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Argyll Array Windfarm". ScottishPower Renewables. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- "The GMFCo Tiree Wave Classic" Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. tireewaveclassic.com. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- "The Professional Windsurfing Association World Cup 2007" STV. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- "Tiree – the outermost Inner-Hebride". Edinburgh University Windsurfing and Surfing Club. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Tyree Gin". thescottishginsociety.com/. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Kurt C. Duwe (September 2006), "Muile, Tiriodh & Colla (Mull, Tiree & Coll)" (PDF), Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies (2nd ed.), Linguae Celticae, 20, retrieved 15 April 2012

- Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL), 2011 Census of Scotland, Table UV12.

- 2011 Census of Scotland, Table KS206SC & Table QS211SC.

- "A thousand music fans flock to Tiree". Oban Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=76kHRG96ciE DarK Island with lyrics

- About Page for Skipinnish

- "Tiree Songbook Launches". The Oban Times. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

Further reading

- Banks, Noel, (1977) Six Inner Hebrides. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7368-4

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

External links

- Map sources for Tiree

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiree. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tiree. |

- Community Website – The Tiree Community Website

- Summit of Tiree – a computer-generated panorama

- Gordon Scott's website keeps people up to date with Tiree events

- Tiree Images – large collection of photographs

- Vaul Golf Club – Golf on Isle of Tiree

- Tiree Baptist Church – Tiree Baptist Church

- Tiree Wave Classic – The Tiree Wave Classic

- An Tirisdeach – The Island's local paper

- Tiree Music Festival – The Island's Annual Music Festival

- Tiree Community Development Trust - Community Led Development Organisation

- An Iodhlann - Tiree's Historical Centre - Museum & Archive