Gigha

Gigha /ˈɡiːə/; Scottish Gaelic: Giogha; Scots: Gigha) or the Isle of Gigha[9] (and formerly Gigha Island)[10] is an island off the west coast of Kintyre in Scotland. The island forms part of Argyll and Bute and has a population of 163 people.[6] The climate is mild with higher than average sunshine hours and the soils are fertile. The main settlement is Ardminish.

| Scottish Gaelic name | Giogha[1] |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ˈkʲi.ə] ( |

| Scots name | Gigha[2] |

| Old Norse name | Guðey[3] |

| Meaning of name | Old Norse, probably "God's island" or "good island" |

Gigha Hotel | |

| Location | |

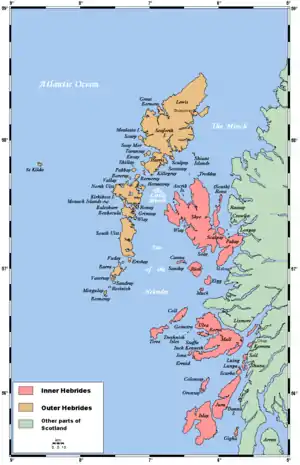

Gigha locator map in the Inner Hebrides | |

Gigha Gigha shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NR647498 |

| Coordinates | 55.68°N 5.75°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Islay |

| Area | 1,395 ha (3,450 acres) |

| Area rank | 41[4] [5] |

| Highest elevation | Creag Bhàn 100 m (330 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 163[6] |

| Population rank | 37 [5] |

| Population density | 11.7/km2 (30/sq mi)[6][7] |

| Largest settlement | Ardminish |

| References | [8] |

Gigha has been inhabited continuously since prehistoric times. It may have had an important role during the Kingdom of Dalriada and is the ancestral home of Clan MacNeill. It fell under the control of the Norse and the Lords of the Isles before becoming incorporated into modern Scotland and saw a variety of conflicts during the medieval period.

The population of Gigha peaked at over 700 in the eighteenth century, but during the 20th century the island had numerous owners, which caused various problems in developing the island. By the beginning of the 21st century the population had fallen to 98. However a "community buy-out" in 2002 has transformed the island, which now has a growing population and a variety of new commercial activities to complement farming and tourism.

Attractions on the island include Achamore Gardens and the abundant wildlife, especially seabirds. There have been numerous shipwrecks on the surrounding rocks and skerries.

Etymology

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | An Dubh Sgeir | |

| Pronunciation: | [ən̪ˠ ˈt̪us̪kʲeɾʲ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Buaidh no Bàs | |

| Pronunciation: | [puəj nɔ paːs̪̪̪] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Cnoc Haco | |

| Pronunciation: | [kɾɔ̃xk haxkɔ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Creag Bhàn | |

| Pronunciation: | [kʰrʲek vaːn] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Creideas Dòchas is Carthannas | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʰɾʲetʲəs̪ ˈt̪ɔːxəs̪ ɪs̪ ˈkʰaɾən̪ˠəs̪̪̪] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | gamhainn | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkãvəɲ] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Gamhna Gioghach | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkãũnə ˈkʲi.əx] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | geodha | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʲɔ.ə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Gioghach | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʲi.əx] ( | |

The Hebrides have been occupied by the speakers of at least four languages since the Iron Age, and many of the names of these islands have more than one possible meaning as a result. Many modern authorities hold that the name "Gigha" is probably derived either from the Norse Guðey or from Gud-øy, meaning either "good island" or "God island".[1][7][11][12] The Norse historical text Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar explicitly calls the island Guðey.[3]

Despite this, Keay and Keay (1994) and Haswell-Smith (2004) suggest the Gaelic name is derived instead from Gjáey, meaning "island of the geo" or "cleft".[7][13] However, Norse gjá normally shows up in Gaelic in the form of geodha. Czerkawaska (2006) also notes that the isle is called "Gug" in a charter of 1309 and also appears as "Gega" on some old maps and speculates that a possible pre-Norse derivation is from the Gaelic Sheela na Gig, a female fertility symbol.[14] Haswell-Smith (2004) also offers the possibility of Gydha's isle after the Norse female name.[7]

A Gigha resident is a Gioghach, also nicknamed a gamhainn ("stirk").[1] Although the most widespread pronunciation of the Gaelic name Giogha is [kʲi.ə], the Southern dialects preserve the fricative: [kʲiɣa] in Kintyre[15] and [kʲɯɣɑ] in Argyllshire.[16]

Geology

The bedrock of Gigha is largely amphibolite, a meta-igneous rock which was probably, before its metamorphism, one or more sills. Some areas, particularly along the east coast are formed from the Erins Quartzite, a metasedimentary rock of Neoproterozoic age (late Precambrian) which falls within the Crinan Subgroup of the Argyll Group, itself a part of the Dalradian sequence which forms most of the southern Highlands. This rock sequence also include pelites and semipelites. The amphibolite is cut by numerous broadly southeast-northwest aligned dykes of olivine-microgabbro dating from the Palaeogene period and forming a part of the ‘North Britain Palaeogene Dyke Suite’. Raised marine deposits cover parts of the island, a product of higher relative sea levels during the early Holocene.[17][18]

Geography

_(14785036095).jpg.webp)

Gigha lies 5 kilometres (3 mi) off the coast of Kintyre and is 9.5 km (6 mi) long in a roughly north-south direction and a maximum of 2.5 km (1 1⁄2 mi) wide. The total area is 1,395 hectares (3,450 acres) and the highest elevation of Creag Bhàn reaches only 100 m (330 ft). The rocky central spine is composed of epidiorite with basalt intrusions.[7][13][19]

The main settlement is Ardminish which is on the south east coast and offers a small anchorage in the sheltered Ardminish Bay. Further to the north is Druimyeon Bay and beyond that West and East Tarbert Bays which (as their names imply) lie astride a small isthmus. There are various farms and associated buildings located throughout the island including Kinerarach and Tarbert in the north[20][21] Ardailly in the west, where there are two holiday homes and a ruined watermill[22] and North and South Druimachro on the east coast south of Ardmininsh.[23][24]

The climate is mild with higher than average sunshine hours and minimum temperatures, and lower than average days of ground frost for Scotland.[7][11] Annual rainfall is typically between 1,000 and 1,290 mm (39 and 51 in).[25]

Surrounding islands

Cara Island lies just offshore to the south, the smaller Craro Island lies to the west and Gigalum Island to the south east. A sandy spit connects Gigha to Eilean Garbh in the north-west. To the north are the rocks called An Dubh Sgeir (a common name meaning "black rock") and Gamhna Giogha. The Sound of Gigha separates Gigha and its attendant isles from mainland Kintyre.[19]

To the west and north west respectively, are the two large islands of Islay and Jura. South west are Rathlin Island and the north of Ireland, which can be seen from Gigha on clear days.[26] Between Jura and Gigha are the rocks of Na Cuiltean and Skervuile Lighthouse. Between Gigha and Port Ellen on Islay is the island of Texa. Eilean Mòr and Island of Danna are little further up the Argyll coast to the north.

There are also many small rocks and skerries (small rock islands) in the seas around Gigha. Asked by a tourist if he knew where they all were, local resident Willie McSporran (see below) replied "No, but I know where they aren't and that's good enough for me".[27]

History

Gigha has been inhabited continuously since prehistoric times, and there are several standing stones on the island. There are many other archaeological sites, including cairns, duns and an ogham stone near to Kilchattan, which has not been deciphered.[13][28]

In the Early Historic Period The domain of the Cenél nGabraín appears to have been centred on Kintyre and Knapdale and may have included Arran, Jura and Gigha. The title king of Kintyre is used of a number of presumed kings of the Cenél nGabrain.[29][30] This would have made Gigha part of Dalriada.

There is some evidence to show that the island might have been the seat of power for Conall mac Comgall, King of Dalriada, in the mid to late 6th century. The Annals of Tigernach refer to a Battle of Delgon (later Cindeglen) in 574, and this has been identified as taking place on Gigha, then referred to as Eilean da Ghallagan,[31][32] although other sources believe the battle took place in Kintyre.[33]

Norse period

Nearby Islay was a centre for Norse control over the Hebrides, and Gigha was later part of the Kingdom of the Isles. The island's name appears to be Norse in origin, although its meaning is disputed, and there are several other Norse placenames in the vicinity, such as Gigalum (i.e. "Gigha - holm") and Cnoc Haco (possibly "Haakon's hill").[34]

In 1849, a Viking grave was found at East Tarbert Bay, which revealed a number of artefacts, including a bronze weighing balance dated to the 10th century.[13][35]

Prior to the Battle of Largs, Haakon IV of Norway is said to have visited the island.[13] According to Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar ("The Saga of Haakon Haakonsson") written by Icelander Sturla Þórðarson in the 1260s:

- King Haco sailed afterwards south to Guðey before Kintyre where he anchored. There King John met him; he came in the ship with Bishop Thorgil. King Haco desired him to follow his banner as he should do. But King John excused himself. He said he had sworn an oath to the Scottish King, and held of him more lands than of the Norwegian Monarch; he therefore entreated King Haco to dispose of all those estates which he had conferred upon him. King Haco kept him with him some time, and endeavoured to incline his mind to fidelity. Many laid imputations to his charge. King Haco indeed had before received bad accounts of him from the Hebrides; for John Langlife-son came to the King, while he was sailing west from Shetland, and told him the news that John King of the Hebrides, breaking his faith, had turned to the Scottish Monarch. King Haco, however, would not believe this till he had found it so.

- During King Haco's stay at Guðey an Abbot of a monastery of Greyfriars waited on him, begging protection for their dwelling, and Holy Church: and this the King granted them in writing.

- Friar Simon had lain sick for some time. He died at Guðey. His corpse was afterwards carried up to Kintire where the Greyfriars interred him in their Church. They spread a fringed pall over his grave, and called him a Saint.[36]

John of Islay

After Edward Balliol's coup against the Bruce regime in 1333, he attempted to court John of Islay, Lord of the Isles. In 1336, Edward confirmed the territories which the Islay lords had acquired in the days of Robert I and awarded John the lands of Kintyre, Knapdale, Gigha, Colonsay, Mull, Skye, Lewis, and Morvern, previously held by magnates still loyal to the Bruces. John, however, never provided Edward with real assistance. Although Balliol's deposition and the restoration of the House of Bruce meant that the grants made to John were void, his pre-1336 possessions were confirmed by King David II in 1343. Moreover, in 1346, John inherited the great Lordship of Garmoran through his brother-in-law Raghnall MacRuaridh. This meant that John's dominions now included all of the Hebrides except Skye, and all of the western seaboard from Morvern to Loch Hourn.[37]

Clan MacNeill

Gigha is the ancestral home of the Clan MacNeill, which possesses its own tartan and Clan badge, both distinctly different from those of the larger and better known Clan MacNeil of Barra (spelt with one "l" in English) who share the same Chief.[38]

The origin of the MacNeills of Taynish, Gigha and Colonsay is obscure. They were hereditary keepers of Castle Sween under the Lords of the Isles during the 15th and 16th centuries. The MacNeill of Gigha, was known as the "chief and principal of the clan and surname of Macneils" in 1530. However, as the power of the Campbells grew and spread into the Inner Hebrides, the influence of the MacNeills of Gigha decreased. At about this time the MacNeils on the more remote island of Barra, far removed from Campbell power, began to grow in prominence and for a long time since have been regarded as "Chief of the Clan and Name".[39]

In 1449 Alexander, Lord of the Isles granted part of the island to Torquil MacNeill of Taynish, the remainder being owned by the monks of Paisley. In 1493 the whole island came under MacNeill control and it remained in their hands, with various brief interludes, until the 19th century. This prize was by no means without its hazards. In 1530 the notorious pirate Ailean nan Sop murdered MacNeill of Taynish and numerous island residents. A dozen years later the title deeds were lost when eleven gentlemen of Gigha were slain by raiders.[7]

Medieval conflict

In 1554 the MacNeills relinquished their Gigha holdings to the MacDonalds, but if anything the conflicts intensified. In 1567 Gigha was "ravaged" by the Macleans of Duart.[40] By 1587, atrocities committed between warring West Highland clans had escalated to such an extent that Parliament devised what is known as the General Band in an effort to quell hostilities. Despite the Governments actions to secure the peace, about this time Lachlan Mor MacLean of Duart ravaged the MacDonald islands of Islay and Gigha, slaughtering 500—600 men. Maclean of Duart then besieged Angus MacDonald of Dunivaig and the Glens at his Castle Dunivaig on Islay.

The siege was only lifted when MacDonald of Dunivaig agreed with MacLean of Duart to surrender half of his lands on Islay. However, despite his agreement with the MacLeans, MacDonald of Dunivaig then invaded the MacLean islands of Mull, Tiree, Coll and Luing. Angus MacDonald of Dunivaig was aided in the action by Donald Gorm Mor MacDonald of Sleat and the MacDonalds of Clanranald, MacIains of Ardnamurchan, MacLeods of Lewis, MacNeills of Gigha, MacAlisters of Loup and the Macfies of Colonsay. Supporting MacLean of Duart were the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan, MacNeils of Barra, MacKinnons of Strathrodle and the MacQuarries of Ulva.[41]

In 1590, Angus of Islay sold out to John Campbell of Cawdor, a junior cousin of the Earl of Argyll. In a move that may well have been pre-arranged Campbell then immediately resold back to Neil MacNeill of Taynish.[42][43] The church at Kilchattan that dates from this period has some "intricately carved medieval grave slabs".[13]

17th century

Visiting in the late 17th century Martin Martin wrote:

This isle is for the most part arable, but rocky in other parts; the mould is brown and clayey, inclining to red; it is good for pasturage and cultivation. The corn growing here is oats and barley. The cattle bred here are cows, horses, and sheep. There is a church in this island called Kilchattan, it has an altar in the east end, and upon it a font of stone which is very large, and hath a small hole in the middle which goes quite through it. There are several tombstones in and about this church; the family of the Macneils, the principal possessors of this isle, are buried under the tombstones on the east side the church, where there is a plot of ground set apart for them. Most of all the tombs have a two-handed sword engraven on them, and there is one that has the representation of a man upon it... This isle affords no wood of any kind, but a few bushes of juniper on the little hills.[44]

William II of Scotland visited the island in 1689, the MacNeill remaining loyal to the crown both then and in the Jacobite rebellion of 1745.[7]

Modern period

In the eighteenth century the population of Gigha peaked at over 600, but had declined to just under 400 by the close of the 19th century. After half a millennium of association, the MacNeills sold the isle for £49,000 to James Williams Scarlett, a nephew of James Scarlett, 1st Baron Abinger in 1865. His son, Lieutenant-Colonel William James Scarlett built the mansion house of Achamore and Gigha remained in the family's hands until 1919.[45][46]

During the 20th century the island had various other owners. Major John Allen bought the island from the Scarletts and sold it to the Richard Hamer in 1937, before passing ownership during World War II to his brother-in-law, Somerset de Chair,[47] who in turn sold to Sir James Horlick in 1944.[48] Horlick is recalled as a generous owner who encouraged dairy farming and created the gardens of Achamore. David Landale then purchased it from the Horlick estate in 1973 retaining it until 1989, during which time he created a fish farm at South Druimachro, which now specialises in halibut with a growing international reputation.[49][24] Over the years little further development took place and some owners are recalled less fondly.[7][50] The island briefly passed into the hands of Malcolm Potier, a property developer,[51] and subsequently to Derek Holt and his family prior to the sale to the Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust.[52] By the 1960s resident numbers had fallen to 163 and by the beginning of the 21st century the population was reduced to only 98 and the housing stock was in poor condition.[53][54]

Overview of population trends

| Year | Population |

| 1755 | 514 |

| 1792 | 614 |

| 1801 | 556 |

| 1821 | 573 |

| 1841 | 550 |

| 1881 | 378 |

| 1891 | 398 |

| Year | Population |

| 1911 | 326 |

| 1931 | 240 |

| 1951 | 190 |

| 1961 | 163 |

| 1981 | 153 |

| 1991 | 143 |

| 2001 | 110 |

| 2011 | 163[6] |

Note: The figures for 1755–1841 include Cara.[7]

Community buy-out

The challenges created by private landlords came to an end in March 2002 when the islanders managed, with help from grants and loans from the National Lottery and Highlands and Islands Enterprise, to purchase the island for £4 million. They now own it through a development trust called the Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust.[55] As a result, 15 March, the day when the purchase went through, is celebrated as the island's "independence day".[56] £1 million of the financial support was in the form of a short-term loan. The money to pay this loan back was largely raised by selling Achamore House (but not the gardens) to Don Dennis, a businessman from California. Dennis now operates a flower essences importing business and a boat tours company from the house, which is also rented out as a bed and breakfast business.[57] An additional £200,000 was raised by the islanders through various fundraising ventures, allowing the loan to be paid back to the Scottish Land Fund on 15 March 2004.[58] Since the community buy out several other private businesses have sprung up on Gigha providing a boost to the local economy, including the multi-award-winning Boathouse Café Bar.[59] The island's population and economy has begun to recover as a result of these activities.[60]

Economy

Gigha's economy is largely dependent on livestock farming, tourism and some limited fishing. There have been some moves to diversify the economy since the community buy-out. There is also a fish farm on the island.[13]

365 hectares (900 acres) of arable land are farmed and relative to its size it is the most fertile and productive island in Scotland.[61] Ayrshire cattle are kept on the island.

In October 2006 it was announced[53] that the population had reached 150 – a rise of more than 50 per cent since the 2002 buy-out. Willie McSporran, former chairman of the Heritage Trust, was quoted as saying: "The trust turned 300 years of population decline on its head by encouraging new development and the growth of the local economy. A sign of the surge of people wanting to relocate to Gigha is that we are struggling to meet the demand for housing despite building 18 new homes." The issues of island ownership are not unique to Gigha and consequently the island has been highlighted in an edition of the BBC series, Countryfile.

In 2010 the historian James Hunter stated that the transfer of ownership had brought about "a spectacular reversal of Gigha's slide towards complete population collapse" and suggested that the UK Government should learn lessons from Gigha and other community buy-outs to inform their "Big Society" plans.[62] Between 2001 and the 2011 census[6] the island's population grew by over 45%.[6] During the same period Scottish island populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702.[63]

Wind turbines

The Heritage Trust set up Gigha Renewable Energy Ltd. to buy and operate three Vestas V27 wind turbines, known locally as The Dancing Ladies or Creideas, Dòchas is Carthannas (Gaelic for Faith, Hope and Charity).[64] They were commissioned on 21 January 2005 and are capable of generating up to 675 kW of power. Revenue is produced by selling the electricity to the grid via an intermediary called Green Energy UK. Gigha residents control the whole project and profits are reinvested in the community.[65] In 2016 two batteries were added to the system.[66]

Transport and infrastructure

There is an unmanned grass landing strip running east/west near the southern end of the island, requiring prior permission for landing. It is one of the closest airstrips to Glasgow International Airport, typically a 20- to 30-minute flight away for small aircraft.

A Caledonian MacBrayne ferry service links the island's only village, Ardminish, to Tayinloan on the Kintyre peninsula of the Scottish mainland. This in turn links to the A83 road.

There is a primary school on the island, but secondary pupils must go to the Mainland for education. Ardminish has the pier, post office and shop.[13] The island's postcode is PA41.

Attractions

Attractions on the island include the 20.2 hectares (50 acres) Achamore Gardens, begun in 1945 by Sir James Horlick and known for its rhododendrons and azaleas, the many sandy beaches and the thirteenth-century St Catan's Chapel ruins. There is also a nine-hole golf course,[11][67] which is currently not in use.

Wildlife

Because it is set on the eastern shores of the Atlantic Ocean, Gigha attracts a wide variety of sea birds such as guillemot and eider, which breed on Eilean Garbh. Inland, ducks such as mallard, teal, wigeon and pochard can be found along with heron, snipe, pheasant and red grouse. The hooded crow and jackdaw are present in considerable numbers, but geese are only occasional visitors. Mammals are under-represented; there are no red deer, stoat, weasel, red fox or hare. In the mid-20th century Gigha had eight boats engaged in fishing for cod and lobster, but commercial activity ceased some time ago.[68]

Shipwrecks

Gigha's coasts have seen numerous wrecks. In August 1886 the Staffa ran aground on Cath Sgier west of Craro. The ship remained on the reef in calm overnight conditions and all crew and 21 passengers were rescued the following morning. On 8 April 1894 the steamship Udea was lost on the same rocks with a cargo of coal and iron. Owned by David MacBrayne, she was en route from Glasgow to Lewis at the time. On 16 September 1940 the British steam liner Aska was bombed by a German aircraft south of Gigha whilst carrying French troops from Gambia. Twelve crewmen died in the attack and 75 survivors were successfully picked up by trawlers. On fire, the Aska drifted onto Cara and was wrecked there. Four years later the Mon Cousu was deliberately sunk in the Sound of Gigha and used for bombing practice. In 1991 the Russian factory ship Kartli was hit by two freak waves off Islay and ran aground at Port Ban after the crew were evacuated. Forty seven crew members were air-lifted to safety but four men were killed in the accident.[69]

Culture

Gigha had a vigorous tradition of harping, represented mainly by the family called Mac an Bhreatnaigh (Galbraith), who were active in Gigha and Kintyre, and it is thought that their descendants were in Gigha until at least 1685.[70] In the 1990s it was reported that many of the island's resident spoke Gaelic [13] although the numbers have declined significantly in recent years.

Gaelic

Gigha has historically been a very strong Gaelic speaking area. Both in the 1901 and 1921 census, the island was reported to be over 75% Gaelic speaking. By 1971, it had dropped to the 25-49.9% range.[71] In the 2001 census, the percentage of Gaelic speakers had dropped to 14%.[71]

Gigha Gaelic was studied extensively by N.M. Holmer in the 1930s, who noted features such as its weak svarabhakti.[72]

In 2008, Henri Macaulay of Gigha Gallery received funding from the Gaelic development body, Bord na Gàidhlig, to run a series of Gaelic-learning weekends on the island as a combined cultural-revival and tourism-development initiative. Conversation and music form the backbone of the weekends. They run through the winter months.[73]

Notable residents

- Seamus McSporran who managed to do 14 jobs during the 31 years of his working life - at the same time.[74] He has also featured in a 2006 English as a foreign or second language study book[75] and in the widely used English textbooks for adults New Headway Elementary and New Headway Elementary 3rd Edition

- Willie McSporran, MBE the first chairman of the Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust. He is the brother of Seamus.[27]

- Giolla Críost Brúilingeach, mid 15th century harper.[70]

- Vie Tulloch, noted sculptor and the island's oldest resident until her death in 2011.[76]

See also

References

Notes

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012. This author specifies "God's island".

- "Map of Scotland in Scots - Guide and gazetteer" (PDF).

- Called such in Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, § 328, line 8 Archived 2012-07-14 at Archive.today, "Then King Hakon sailed south long Kintyre and lay at the place that is called Guðey" and § 329, line 7, "Then they went out under Guðey, to King Hakon"; see A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, vol. ii, pp. 617, 620

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 502–03. Modified to include bridged islands.

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 37–41.

- Infobox source is Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 37–41 unless otherwise stated.

- "Isle of Gigha/Giogha". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Old Maps of Britain and Europe". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Murray (1977) pp. 115–16.

- Czerkawaska (2006) pp. 35–36.

- Keay & Keay (1994) p. 423.

- Czerkawaska (2006) pp. 35–37. This author accepts that the possibility of a connection with Sheela na Gig is "a remote and contentious one!" and also suggests "island of the good harbour" rather than simply "good island".

- Holmer, N. The Gaelic of Kintyre Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin 1962, p.7

- Holmer, N. Studies on Argyllshire Gaelic K. Humnistiska Vetenskaps, Uppsala 1938, p.175

- "Onshore Geoindex". British Geological Survey. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Sound of Gigha Sheet 20 and part of 21W Solid and Drift Edition". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Explorer 357: Kintyre North, Knapdale South & Isle of Gigha. (2001) Southampton. Ordnance Survey.

- "Kinerarach". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Tarbert". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Ardailly". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "North Druimachro". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "South Druimachro". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "1971-2000 mapped averages" Met Office. Retrieved 16 September 2008. Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Murray (1966) p. 2.

- Czerkawaska (2006) p. 189.

- It is badly weathered and the etching is probably a name on a tombstone. Various attempts have been made to decipher it e.g. "Vicula Maq Comgini" (Fiacal, son of Coemgen). See Czerkawaska (2006) p. 99.

- Thomson (1994) p. 40 Cenél nGabrain

- Grimble (1985) p. 9 Chap. 2 Isles of the Saints

- McLeod, John "Remarks on the Supposed Site of Delgon or Cindelgen, the Seat of Connal, King of Dalriada, AD 563." (December 1983) (pdf) Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Retrieved 18 March 2007. The Scottish antiquarian W.F. Skene originally identified this battle site as being in west Knapdale. He later revised his opinion on evidence presented to him by the archaeologist Hugh Maclean of Tarbet.

- Innes, C. (1832)"Syllabus of Scottish Cartularies" Archived 2011-06-07 at the Wayback Machine (pdf) Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- Onomasticon Godelicum. CELT/Documents of Ireland

- Czerkawaska (2006) pp. 115–16.

- Czerkawaska (2006) p. 113.

- "The Norwegian account of Haco's expedition against Scotland, A.D. MCCLXIII." Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Oram, Richard "The Lordship of the Isles". p. 124; Michael Brown (2004) The Wars of Scotland. Edinburgh. p. 271.

- "MacNeill of Colonsay" Archived 2006-12-30 at the Wayback Machine ScotClans. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

-

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk, Iain. The Highland Clans. London. Barrie & Rockliff. 1967.

- Czerkawaska (2006) p. 130.

- Roberts (1999) pp. 91—92.

- Czerkawaska (2006) p. 131.

- Grimble (1985) p. 45 Chap. 5 Campbell Takeover

- Martin (1703) "The Isle Gigha".

- Czerkawaska (2006) pp. 179-80

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 39 states that Gigha was bought by "Captain William Scarlet of Thryberg in Yorkshire" who also built Achamore House.

- "Somerset de Chair". everything2.com. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- Czerkawaska (2006) p. 181

- Ross, David (20 Sep 2008) "Out to make a splash in the market". Glasgow. The Herald. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- Czerkawaska (2006) pp. 213-214.

- Farquharson, Kenny (8 Oct 2006) "The laird who fell from grace". London. The Times. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- Womersley, Tara (30 Oct 2001) "Now Gigha's owner must decide on bids". London. The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- Ross, J (2006-10-13). "Island of opportunity welcomes a population explosion". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- Czerkawaska (2006) pp. 214-215.

- "Isle of Gigha website". Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- "Island officially changes hands". BBC News Online. 15 March 2002. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- Linda Gannell (19 September 2007). "Besting Mick Jagger". The New York Times Great Homes. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- "How Gigha was bought by the community". Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 2007-09-17. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- "Boathouse Café Bar". boathouse-bar.com. Archived from the original on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- "The History of Gigha" Archived 2008-09-21 at the Wayback Machine Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- Murray (1973) p. 34.

- "Ross, David (20 August 2010) "Cameron should visit Gigha to see the Big Society in action, says historian". Glasgow: The Herald.

- "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Let's Talk Renewables" (PDF). HIE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- "Green Energy press release". greenenergy.uk.com. 26 January 2005. Archived from the original on 21 December 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- "redT's energy storage machines ready for Isle of Gigha project". Renewablesnow.com. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- "Gigha Today" Archived 2008-09-13 at the Wayback Machine Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust. Retrieved 9 September 2008. Gigha Boats and Activity Centre is another new enterprise brought to the island following the buy out - allowing tourists and islanders alike to get a fresh perspective on the island and to discover seals, dolphins and other wildlife that surrounds it. See "Gigha Boats Activity Centre" Gigha.net. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Murray (1966) pp. 65–66.

- Baird (1995) pp. 98–102.

- Thomson (1994). p. 117 Harpers

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) 1901-2001 Gaelic in the Census (PowerPoint ) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- Holmer, N.M. (1938) Studies on Argyllshire Gaelic. Uppsala & Leipzig. (Mainly discusses Gigha and Islay, as well as Skye.)

- "Gaelic Classes are back!". Isle of Gigha Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- Czerkawaska (2006) p. 3.

- Soars (2006) p. 24-25.

- "Open Country" June 2005.BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

Sources

- Anderson, Alan Orr (1922). "Early Sources of Scottish History A.D. 500 to 1286". ii. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Baird, Bob (1995) Shipwrecks of the West of Scotland. Glasgow. Nekton Books. ISBN 1-897995-02-4

- Czerkawaska, Catherine (2006) God's Islanders: A History of the People of Gigha. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-297-2

- Grimble, Ian (1985) Scottish Islands British Broadcasting Corporation (London) ISBN 0-563-20361-7

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255082-2

- Martin, Martin (1703) "A Voyage to St. Kilda" in A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland, Appin Regiment/Appin Historical Society. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Murray, W.H. (1966) The Hebrides. London. Heinemann.

- Murray, W.H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland. London. Eyre Methuen.

- Murray, W.H. (1977) The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland. London. Collins.

- Roberts, John L. (1999) Feuds, Forays and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans, 1475-1625. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-6244-8

- Soars, Liz and John (2006) New Headway Elementary 3rd Edition. Oxford. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-471509-6

- Thomson, Derick (ed.) (1994) The Companion to Gaelic Scotland. Glasgow. Gairm. ISBN 1-871901-31-6