Shannon–Erne Waterway

The Shannon–Erne Waterway (Irish: Uiscebhealach na Sionainne is na hÉirne; is a canal linking the River Shannon in the Republic of Ireland with the River Erne in Northern Ireland. Managed by Waterways Ireland, the canal is 63 km (39 mi) in length, has sixteen locks and runs from Leitrim village in County Leitrim to Upper Lough Erne in County Fermanagh.

| Shannon–Erne Waterway Uiscebhealach na Sionainne is na hÉirne Shannon–Erne Wattèrgate | |

|---|---|

Castlefore Lock on the Shannon–Erne Waterway | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 63 km (39 miles) |

| Locks | 16 |

| Status | Open |

| Navigation authority | Waterways Ireland |

| History | |

| Date of first use | 1860 |

| Date closed | 1870 |

| Date restored | 1994 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Upper Lough Erne |

| End point | Leitrim |

| Connects to | River Shannon (Lough Allen Canal) |

Shannon–Erne Waterway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The official opening of the Shannon–Erne Waterway took place at Corraquill Lock, just south of Teemore in the south of County Fermanagh, on 23 May 1994.

History

The earliest known name of the Shannon–Erne Waterway was the River Gráinne (Sruth Gráinne in Irish, meaning The Gravelly River). The earliest surviving mention of the river name is in a poem composed about 1291 which gives the name as Sruth Gráinne:

- The Gráinne River, that clear and fairest of streams,

- never ceases its moaning as it flows through the wood.

- Sruth Gráinne ar a ghuth ní ghabh

- Sruth glan áille tre fhiodh.[1]

The Annals of Loch Cé for the year 1457 state:

The victory of the Graine was gained by Mag Uidhir over Lochlainn, the son of Tadhg O'Ruairc, i.e. O'Ruairc.

The Annals of Ulster for the year 1457 state:

Great war arose this year between Mag Uidhir, namely, king of Fir-Manach and Ua Ruairc, namely, Lochlann, son of Tadhg Ua Ruairc. Mag Uidhir and Ua Ruairc appointed a meeting with each other opposite Ath-Conaill Mag Uidhir and Brian, son of Philip Mag Uidhir, went with a few people—that is, six horsemen and three score footmen—to meet Ua Ruairc. When Ua Ruairc and the Tellach-Eathach and Tellach-Dunchadha learned that Mag Uidhir was accompanied by only a small force, they gave him a hostile meeting. When Mag Uidhir saw the deceit practised on him, he went forward to Gort-an-fedain. There a battalion of kern and a battalion of gallowglasses of the people of Ua Ruairc overtook him. Then Mag Uidhir and Brian Mag Uidhir, with the six that were on horses and the three score kern, turned on them and routed the people of Ua Ruairc spiritedly, felicitously on that occasion and inflicted the defeat of Ath-Conaill and of the Graine-namely, a river that is between Fir-Manach and the Breifne-upon them. Mag Uidhir and his people then, returned with spoils joyfully. And the kern of Mag Uidhir carried with them sixteen heads of the nobles of the people of Ua Ruairc to the town of Mag Uidhir and they were placed on the palisade of the court-yard of Mag Uidhir and so on.

The 1609 Plantation of Ulster baronial map for the Barony of Loughtee, County Cavan, depicts the river as Graine Flumen (Latin for 'Graine River').

After the Cromwellian settlement of Ireland in the 1650s, the river was renamed as the Woodford River, after the Woodford Demesne in County Leitrim, through which the river flowed. Taylor & Skinner Maps of the Roads of Ireland in 1777 depicts it as the Woodford River.[2] After the river was canalised in the 1850s it was renamed as the Woodford Canal and sometimes as the Ballinamore and Ballyconnell Canal

The grand plan of linking the river systems of the Erne and the Shannon with Lough Neagh was behind the planning for several of the Irish canals, and the first attempt at a link between the Erne and the Shannon was made in 1780, along the Woodford river, from Belturbet to Ballyconnell. Richard Evans carried out the work, which was financed by a grant of £1,000 from parliament. He built a lock near Carrowl, but failed to obtain any more grants, and the project ceased. In 1790, there was a scheme to connect Lower Lough Erne to the sea at Ballyshannon, which would involve the construction of twelve locks, but only one was built,[3] and the scheme foundered in 1792, due to a failure to raise enough capital.[4]

The next survey of the Woodford river was made in 1793 by William Chapman, who estimated that Garadice Lough could be reached for £5,000, from where he believed that a link to the Shannon should be possible. Eight years later, the Directors General asked Richard Evans, who had carried out the work in 1780, to estimate the cost of a link from the Shannon to the Erne, and also to reappraise the link from the Lower Erne at Belleek to the sea at Ballyshannon. Evans estimated that the two projects would cost £48,000, but the Directors General took no action, and this was the last time that the link to the sea was considered.[5]

In 1831, The Office of Public Works (The O.P.W., sometimes known as the Board of Works) was created, presided over by the Commissioners of Public Works, and one of The O.P.W.'s tasks was to find public schemes that would create employment. Accordingly, William Mulvany carried out the next survey at their request, at a time when work had begun on the Ulster Canal, which would provide the link onwards to Lough Neagh. The powers of the Commissioners of Public Works were increased in 1842, so that their remit included navigations, drainage and water power works. The Ulster Canal wanted the link to the Shannon completed, while local landowners wanted better drainage of the area, and these two factors finally convinced the Commissioners that they should act. The scheme would combine navigation and drainage, and plans were drawn up by John McMahon, an engineer working for the Board of Works. He estimated that the work would cost £100,000.[6]

When work began on the Ballinamore and Ballyconnell Canal in 1846, it was financed by The O.P.W., with John McMahon setting out the line and William Mulvany acting as the engineer in charge.[4] The mix of drainage and navigation was always an awkward combination, since the first required low water levels and the second required high water levels. The engineering would have been simpler if two separate schemes had been built, as would the finances, since the drainage work had to be accounted for separately, and there were often delays while waiting for funding which was part of the other scheme. There were also problems with millers and eel fisheries, and surprisingly for a scheme designed to provide employment, difficulty with finding sufficient numbers of labourers to carry out the work. At the start of the project, over 7,000 were employed, but this reduced to 2,500 in its later stages.[6]

A navigation channel was dredged through the six loughs which formed part of the canal using steam dredgers. The locks down to Lough Erne were all constructed with large weirs, and there were considerable problems with flooding from the Woodford River during construction. Between Lough Scur and Leitrim, the Leitrim River was enlarged, and eight locks were built. It soon became obvious that the original estimates were totally inadequate, and in 1852 there was an investigation into the Board of Works, since they seemed unable to deliver any projects within budget. Mulvany became the scapegoat, and was blamed for the overrun. He made cutbacks, reducing the depth from 6 feet (1.8 m) to 4.5 feet (1.4 m), although in places the navigation was shallower than this. Despite the stringency, towpaths were built on the canal sections at huge cost, even though the loughs made it impossible to use horse power for much of the distance, and boats with steam engines were already working on the Shannon.[7]

The first boats to use the canal from Ballinamore began to do so in 1858. By 1859 the cost had risen to £276,992, and there was a dispute as to who should pay the difference between that and the original estimate. Following a public enquiry, £30,000 was paid by each of the counties through which the canal ran, and the rest was funded by the government. Management was to be by a group of navigation trustees and a separate group of drainage trustees, which again provided conflict. The canal was handed over to them on 4 July 1860. Within months the engineer and secretary of the trustees, J. P. Pratt, had compiled a long list of problems. The records showed that only eight boats used the canal between 1860 and 1869, generating tolls of £18, and with this level of usage, there was little incentive to put things right.[8]

Decline

Two enquiries held at the time give an insight into the canal. The Crighton Committee of Enquiry was set up in 1878 to investigate the performance of the Board of Works, and following their findings, the Monck commission looked at the issues of a route from Belfast to Limerick. As part of the evidence collected, Pratt related that he had ceased to maintain it after 1865, since there was no traffic, and John Grey Vesey Porter, one of the trustees, described a three-week journey along the canal in a steamer in 1868, which had only been achieved by Pratt moving the water from pound to pound to keep the boat afloat. He declared the whole project to be one of the most shameful pieces of mismanagement in any county. In 1887, the Cavan and Leitrim Railway arrived in the area, and were sufficiently confident that the canal would not be used that they built low bridges over it, preventing navigation. The railway was not a commercial success either, and was another drain on local resources.[9]

The Shuttleworth Commission recommended that the upper lock gates should be repaired in 1906, to prevent further damage to the structures of the waterway, but with no funds available, the navigation trustees concentrated on minor bridge repairs, to keep landowners and local authorities happy, and by 1948 they had ceased to function. Local authorities had to assume responsibility for bridge repairs, and there were ongoing problems with flooding.[10]

A new waterway

The canal lay moribund until the 1960s, when the growth in pleasure boating on the Shannon led enthusiasts to consider whether it could be restored. By 1969, Leitrim Council and the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland were asking for a full survey to be carried out.[12] In 1973 at the Sunningdale Conference, during discussion on functions of the Council of Ireland, Leslie Morrell inserted the Waterway into the list of possible cross-border works. Here things lay until 1988, when an engineering and feasibility study, funded by the International Fund for Ireland, examined the issues surrounding reinstatement of the canal, which lay across the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.The NI Water Council, then being chaired by Leslie Morrell, gave enthusiastic support and gained the approval of the Direct Rule Administration for the proposal. In June 1989, Charles Haughey, the Taoiseach, announced that the two governments had decided to adopt the proposal as a flagship cross-border project. In order for the project to take place, the powers of the original trustees, which had passed to the local authorities along its route, were transferred to the Office of Public Works. Work commenced in November 1990 and the canal was opened to traffic on 23 May 1994 on time and within the budget of £30m. It was essentially a new navigation along the line of the original waterway, which had never been properly completed in the first place.[13]

The work involved major reconstruction of many of the structures, to make them suitable for modern cruisers. The eight locks between Lough Scur and Lough Erne were new concrete structures, and were widened to 19.8 feet (6 m), but were faced with stone from the original locks. The eight locks down to the Shannon were in better condition, and were repaired, so retain their original width of 16.5 feet (5 m). The locks are fully automatic, and are operated by the boat crews, using a smart card to activate the control panel, although they can only be used when waterways staff are working. Once restored, the canal was renamed, becoming the Shannon–Erne Waterway, to reflect its purpose of linking the two river systems, and it was opened by Dick Spring, the Irish Foreign Minister and Sir Patrick Mayhew, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland at the time. One unfortunate result of the scheme has been the invasion of the Erne system by the zebra mussel, a non-native species which travelled along the waterway from the Shannon.[14]

Course of the waterway

The waterway has three natural sections: a still-water canal from the Shannon at Leitrim to Kilclare, which has eight locks; a summit level which includes Lough Scur, and a river navigation from Castlefore, near Keshcarrigan, through Ballinamore and Ballyconnell to the Erne, which has another eight locks.[15]

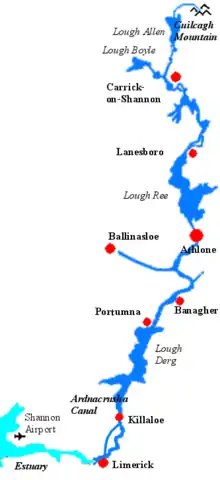

Maps

Map of Shannon

Map of Shannon Location map of Lough Erne

Location map of Lough Erne

Bibliography

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2002). The Inland Waterways of Ireland. Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-0-85288-424-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delany, Ruth (2004). Ireland's Inland Waterways. Appletree Press. ISBN 978-0-86281-824-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flanagan, Patrick (1994). The Shannon-Erne Waterway. Dublin: Wolfhound Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- McKenna, L. (1947). The Book of Magauran. Poem 2, verse 29.

- Taylor; Skinner. "Maps of the Roads of Ireland Surveyed 1777".

- Delany 2004, pp. 155–156

- Flanagan 1994

- Delany 2004, pp. 156–157

- Delany 2004, p. 157

- Delany 2004, pp. 157–158

- Delany 2004, pp. 158–159

- Delany 2004, pp. 155, 159–160

- Delany 2004, p. 160

- "46th Annual Erne Boat Rally" (PDF). Inland Waterways Association of Ireland.

- Cumberlidge 2002, p. 98

- Delaney 2004, pp. 199–201

- Cumberlidge 2002, pp. 98–99, 102

- Cumberlidge 2002, p. 99