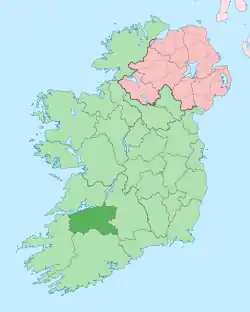

County Limerick

County Limerick (Irish: Contae Luimnigh) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the province of Munster, and is also part of the Mid-West Region. It is named after the city of Limerick. Limerick City and County Council is the local council for the county. The county's population at the 2016 census was 194,899 of whom 94,192 lived in Limerick City, the county capital.[2][3]

County Limerick

Contae Luimnigh | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): The Treaty County | |

| Motto(s): Cuimhnigh ar Luimneach (Irish) "Remember Limerick" | |

| |

| Country | Republic of Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| Dáil Éireann | Limerick City Limerick County |

| EU Parliament | South |

| Established | 1210[1] |

| County town | Limerick |

| Government | |

| • Type | City and County Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,756 km2 (1,064 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 10th |

| Highest elevation | 918 m (3,012 ft) |

| Population | 194,899 |

| • Rank | 9th |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing keys | V35, V42, V94 (primarily) |

| Telephone area codes | 061, 069 (primarily) |

| Vehicle index mark code | L (since 2014) LK (1987–2013) |

| Website | www |

Geography and political subdivisions

Limerick borders four other counties: Kerry to the west, Clare to the north, Tipperary to the east and Cork to the south. It is the fifth largest of Munster's six counties in size, and the second largest by population. The River Shannon flows through the city of Limerick into the Atlantic Ocean at the north of the county. Below the city, the waterway is known as the Shannon Estuary. Because the estuary is shallow, the county's most important port is several kilometres west of the city, at Foynes. Limerick City is the county town and is also Ireland's third largest city. It also serves as a regional centre for the greater Mid-West Region. Newcastle West, Kilmallock & Abbeyfeale are other important towns in the county.

Baronies

There are fourteen historic baronies in the county. While baronies continue to be officially defined units, they are no longer used for many administrative purposes. Their official status is illustrated by Placenames Orders made since 2003, where official Irish names of baronies are listed under "Administrative units".

- Clanwilliam (County Limerick) - Clann Liam

- Connello Lower - Conallaigh Íochtaracha

- Connello Upper - Conallaigh Uachtaracha

- Coonagh - Uí Chuanach

- Coshlea - Cois Laoi

- Coshma - Cois Máighe

- Glenquin - Gleann an Choim

- Kenry - Caonraí

- Kilmallock - Cill Mocheallóg

- North Liberties - Na Líbeartaí Thuaidh

- Owneybeg - Uaithne Beag

- Pubblebrien - Pobal Bhriain

- Shanid - Seanaid

- Smallcounty - An Déis Bheag

Most populous towns

Limerick City is the county capital and is shown in bold.

| Rank | Town | Population (2016 census) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Limerick | 94,192 |

| 2 | Newcastle West | 6,619 |

| 3 | Annacotty | 2,930 |

| 4 | Castleconnell | 2,107 |

| 5 | Abbeyfeale | 2,023 |

| 6 | Kilmallock | 1,668 |

| 7 | Caherconlish | 1,476 |

| 8 | Rathkeale | 1,441 |

| 9 | Murroe | 1,377 |

| 10 | Croom | 1,159 |

| 11 | Askeaton | 1,137 |

| 12 | Adare | 1,129 |

Physical geography

One possible meaning for the county's name in Irish Luimneach is "the flat area"; this description is accurate as the land consists mostly of a fertile limestone plain. Moreover, the county is ringed by mountains: the Slieve Felims to the northeast, the Galtees to the southeast, the Ballyhoura Mountains to the south, and the Mullaghareirk Mountains to the southwest and west. The highest point in the county is located in its south-east corner at Galtymore (919 m), which separates Limerick from County Tipperary. Limerick shares the 3rd-highest county peak in Ireland with Tipperary. The county is not simply a plain, its topography consists of hills and ridges. The eastern part of the county is part of the Golden Vale, which is well known for dairy produce and consists of rolling low hills. This gives way to very flat land around the centre of the county, with the exception being Knockfierna at 288 m high. Towards the west, the Mullaghareirk Mountains (Mullach an Radhairc in Irish, roughly meaning "mountains of the view") push across the county offering extensive views east over the county and west into County Kerry.

Volcanic rock is to be found in numerous areas in the county, at Carrigogunnell, at Knockfierna, and principally at Pallasgreen/Kilteely in the east, which has been described as the most compact and for its size one of the most varied and complete carboniferous volcanic districts in either Britain and Ireland.

Tributaries of the Shannon drainage basin located in the county include the rivers Mulcair, Loobagh, Maigue, Camogue, Morning Star, Deel, and the Feale.

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 9,759 | — |

| 1505 | 10,846 | +11.1% |

| 1506 | 11,045 | +1.8% |

| 1510 | 11,173 | +1.2% |

| 1515 | 11,520 | +3.1% |

| 1530 | 11,933 | +3.6% |

| 1535 | 12,577 | +5.4% |

| 1550 | 12,614 | +0.3% |

| 1555 | 12,880 | +2.1% |

| 1580 | 13,110 | +1.8% |

| 1585 | 13,580 | +3.6% |

| 1600 | 13,777 | +1.5% |

| 1606 | 14,107 | +2.4% |

| 1610 | 14,616 | +3.6% |

| 1611 | 15,194 | +4.0% |

| 1613 | 15,590 | +2.6% |

| 1616 | 16,281 | +4.4% |

| 1621 | 17,368 | +6.7% |

| 1626 | 17,771 | +2.3% |

| 1631 | 18,455 | +3.8% |

| 1636 | 19,542 | +5.9% |

| 1641 | 20,629 | +5.6% |

| 1645 | 21,716 | +5.3% |

| 1646 | 21,755 | +0.2% |

| 1653 | 22,803 | +4.8% |

| 1656 | 23,890 | +4.8% |

| 1659 | 24,977 | +4.6% |

| 1821 | 277,477 | +1010.9% |

| 1831 | 315,355 | +13.7% |

| 1841 | 330,029 | +4.7% |

| 1851 | 262,132 | −20.6% |

| 1861 | 217,277 | −17.1% |

| 1871 | 191,936 | −11.7% |

| 1881 | 180,632 | −5.9% |

| 1891 | 158,912 | −12.0% |

| 1901 | 146,098 | −8.1% |

| 1911 | 143,069 | −2.1% |

| 1926 | 140,343 | −1.9% |

| 1936 | 141,153 | +0.6% |

| 1946 | 142,559 | +1.0% |

| 1951 | 141,239 | −0.9% |

| 1956 | 137,881 | −2.4% |

| 1961 | 133,339 | −3.3% |

| 1966 | 137,357 | +3.0% |

| 1971 | 140,459 | +2.3% |

| 1979 | 157,407 | +12.1% |

| 1981 | 161,661 | +2.7% |

| 1986 | 164,569 | +1.8% |

| 1991 | 161,956 | −1.6% |

| 1996 | 165,042 | +1.9% |

| 2002 | 175,304 | +6.2% |

| 2006 | 184,055 | +5.0% |

| 2011 | 191,809 | +4.2% |

| 2016 | 194,899 | +1.6% |

| [4][5][6][7][8][9][2] | ||

It is thought that humans had established themselves in the Lough Gur area of the county as early as 3000 BC, while megalithic remains found at Duntryleague date back further to 3500 BC. The arrival of the Celts around 400 BC brought about the division of the county into petty kingdoms or túatha.

From the 4th to the 11th century, the ancient kingdom of the Uí Fidgenti was approximately co-extensive with what is now County Limerick, with some of the easternmost part the domain of the Eóganacht Áine. The establishment of Limerick as a town and base by the Danes in the mid 900's, and their alliance with Irish families, including their alliance with Donnubán mac Cathail of the O'Donovans, resulted in significant conflicts with neighbouring clans, principally the O'Briens of Dál gCais, who raided into the Limerick area on a regular basis. The O'Briens retained their political power until late in the 1100s. The establishment of King John's castle in Limerick, and the granting of formerly Ui Fidgenti lands to the FitzGeralds, both circa 1200, and the resultant competition for Ui Fidgenti lands by other Anglo Norman families, resulted in a transfer of power from the Ui Fidgenti's leading families (O'Donovan and Collins) to the new landholders. The ancestors of both Michael Collins and the famous O'Connells of Derrynane were also among the septs of the Uí Fidgenti.

As the Ui Fidgenti were the ruling clan in the Limerick after 400 a.d., the Uí Fidgenti still made a substantial contribution to the population of the central and western regions of County Limerick. Their capital was Dún Eochair, the great earthworks of which still remain and can be found close to the modern town of Bruree, on the River Maigue. Bruree is a derivation of Brugh Righ, or Fort of the King. Catherine Coll, the mother of Éamon de Valera, was a native of Bruree and this is where he was taken by her brother to be raised.

St. Patrick brought Christianity to Limerick area in the 5th Century. Various annals record that St. Patrick quarreled with the chief of the Ui Fidgenti (who, though hosting St. Patrick, had his horses stolen as he journeyed into their territory) but was embraced by the brother of the chief. The adoption of Christianity resulted in the establishment of important monasteries in Limerick, at Ardpatrick, Mungret and Kileedy. From this golden age in Ireland of learning and art (5th – 9th Centuries) comes one of Ireland's greatest artifacts, The Ardagh Chalice, a masterpiece of metalwork, which was found in a west Limerick fort in 1868. It is believed that the chalice had been taken by raiding Danes during the 9th century, ending up in the territory of their Irish allies, the O'Donovans of the Ui Fidgenti.

Following the establishment of the Ui Fidgenti circa 377 a.d., there were few significant changes in political control until the arrival of the Vikings in the 9th century, which ultimately brought about the establishment of the city on an island on the River Shannon in 922. The death of Domnall Mór Ua Briain, King of Munster in 1194 resulted in the invading Normans taking control of Limerick, and in 1210, the County of Limerick was formally established as Ui Fidgenti lands were granted to what would become the Fitzgerald dynasty. Over time, the Normans became "more Irish than the Irish themselves" as the saying goes. The Tudors in England wanted to curb the power of these Gaelicised Norman Rulers and centralise all power in their hands, so they established colonies of English in the county. Distrust by England of the leading Fitzgerald families, and the execution of the several of the Fitzgeralds of Kildare, precipitated a revolt against English Rule in 1569. Th resultant savage war in Munster, known as the Desmond Rebellions, laid waste to the province, and ended with confiscation of the vast estates of the Geraldines and other Irish families that had participated in the ten years of war.

The county was to be further ravaged by war over the next century. After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Limerick city was taken in a siege by Catholic general Garret Barry in 1642. The county was not fought over for most of the Irish Confederate Wars, of 1641–53, being safely behind the front lines of the Catholic Confederate Ireland. However it became a battleground during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649–53. The invasion of the forces of Oliver Cromwell in the 1650s included a twelve-month siege of the city by Cromwell's New Model Army led by Henry Ireton. The city finally surrendered in October 1651. One of Cromwell's generals, Hardress Waller was granted lands at Castletown near Kilcornan in County Limerick. During the Williamite War in Ireland (1689–1691) the city was to endure two further sieges, one in 1690 and another in 1691. It was during the 1690 siege that the infamous destruction of the Williamite guns at Ballyneety, near Pallasgreen was carried out by General Patrick Sarsfield. The Catholic Irish, comprising the vast majority of the population, had eagerly supported the Jacobite cause, however, the second siege of Limerick resulted in a defeat to the Williamites. Sarsfield managed to force the Williamites to sign the Treaty of Limerick, the terms of which were satisfactory to the Irish. However the Treaty was subsequently dishonoured by the English and the city became known as the City of the Broken Treaty.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw a long period of persecution against the Catholic majority, many of whom lived in poverty. In spite of this oppression, however, the famous Maigue Poets strove to keep alive their ancient Gaelic Poetry in towns like Croom and Bruree. The Great Famine of the 1840s set in motion mass emigration and a huge decline in Irish as a spoken language in the county. This began to change around the beginning of the 20th century, as changes in law from the British Government enabled the farmers of the county to purchase lands they had previously only held as tenants, paying high rent to absentee landlords.

Limerick saw much fighting during the War of Independence of 1919 to 1921 particularly in the east of the county. The subsequent Irish Civil War saw bitter fighting between the newly established Irish Free State soldiers and IRA "Irregulars", especially in the city (See Irish Free State offensive).

Local government and politics

Local government

The local government area of County Limerick is under the jurisdiction of Limerick City and County Council. The council has responsibility for local services such as sanitation, planning and development, libraries, collection of motor taxation, local roads and social housing in the city. The council comprises elected ward councillors with an appointed full-time CEO as both city & county manager. Until June 2014 the county's local government in the county was administered by two separate authorities; Limerick City Council and Limerick County Council. In October 2012 the Government of Ireland published Putting People First- Action Programme for Effective Local Government which set out Government policy for reforms across all the main areas of local government in Ireland. Among the recommendations was the merging of Limerick City Council with Limerick County Council. The changes came into effect on 1 June 2014.[10] Each local council ranks equally as first level local administrative units of the NUTS 3 Mid-West Region for Eurostat purposes.

Councillors

For the 2014 Local Elections, the City and County Councils merged so the number of council seats was reduced to 40. The current constituencies or municipal districts are:

- Adare-Rathkeale - 6 Seats

- Cappamore-Kilmallock - 7 Seats

- Limerick City East - 8 Seats

- Limerick City North - 6 Seats

- Limerick City West - 7 Seats

- Newcastle West - 6 Seats

Constituencies

The county is part of the South constituency for the purposes of European elections. For elections to Dáil Éireann, the county is part of two constituencies: Limerick City,[11] and Limerick County. Together they elect 7 deputies (TDs) to the Dáil.

Irish language

There are 2,322 Irish speakers in County Limerick attending the six gaelscoileanna (Irish language primary schools) and three gaelcholáistí (Irish language secondary schools).[12]

Culture

In 2014, Limerick became Ireland's inaugural National City of Culture, with a wide variety of artistic and cultural events occurring at various locations around the city. The Limerick City Gallery of Art on Pery Square is the city's chief venue for contemporary art exhibitions. Theatres include the Limetree Theatre, Mary I; the University Concert Hall and the Millennium Theatre, LIT all in the city. Others include the Friar's Gate in Kilmallock and the Honey Fitz in Lough Gur. The city has an active music scene, which has produced bands such as The Cranberries. The Limerick Art Gallery and the Art College cater for painting, sculpture and performance art of all styles. Limerick is also home to comedians The Rubberbandits, D'Unbelievables (Pat Shortt and Jon Kenny) and Karl Spain. Its most famous acting son is Richard Harris. The city is the setting for Frank McCourt's memoir Angela's Ashes and the film adaptation. A limerick is a type of humorous verse of five lines with an AABBA rhyme scheme: the poem's connection with the city is obscure, but the name is generally taken to be a reference to Limerick city or County Limerick,[33][34] sometimes particularly to the Maigue Poets who were based in Croom and its environs, and may derive from an earlier form of nonsense verse parlour game that traditionally included a refrain that included "Will [or won't] you come (up) to Limerick?" Riverfest is an annual summer festival held in Limerick. The festival was begun in 2004. Other festivals include the Knights of Westfest in Newcastle West, Fleadh by the Feale in Abbeyfeale and the Ballyhoura International Walking Festival. The west of the county is known for its Irish music, song and dance and is part of the Sliabh Luachra area of traditional Irish music along the borders of County Cork and County Kerry.

Places of interest

Transport

Rail

The main railway station in Limerick is called Colbert station, named after West Limerick man Con Colbert who was executed following the Easter Rising of 1916. Limerick has three operational railway lines passing through it,

- the Limerick-Ballybrophy railway line leading to North Tipperary stopping at Castleconnell, Birdhill, Nenagh Cloughjordan and Roscrea

- the Ennis line through County Clare which continues on to Galway as part of the Western Railway Corridor

- the Limerick Junction line which is the busiest line, connecting Limerick to the Cork-Dublin Heuston line and to the Limerick Junction-Clonmel-Waterford line.

In addition, a line exists leading to Foynes however the last revenue service was in 2000.

Road & bus

The M7 is the main road linking Limerick with Dublin. The M/N20 connects the county with Cork. The N21 road links Limerick with Tralee and travels through some of the main county towns such as Adare, Rathkeale, Newcastle West and Abbeyfeale. The N/M18 road links the county to Ennis and Galway while the N24 continues south eastwards from Limerick towards Waterford travelling through villages such as Pallasgreen and Oola. The N69, a secondary route travels from Limerick City along the Shannon Estuary through Clarina, Kildimo, Askeaton, Foynes & Glin and continues towards Listowel in County Kerry. It is the main road linking the Port of Foynes with Limerick city, although plans are in place to upgrade this road to motorway status. The county's regional/national bus hub is located beside Colbert Station and connects most parts of the city and county.

Air

No commercial airports are situated in County Limerick and the region's needs are serviced from Shannon Airport just 25 km away in County Clare which has many flights to Europe and North America. However some in the south of the county may also use Kerry Airport and Cork Airport which are also within 1 hour's drive. Coonagh Aerodrome located just outside the city close to the Clare border is used for light pleasure craft. Foynes, a village in the west of the county, had a unique part to play in the development of aviation. During the late 1930s and early 1940s, land-based planes lacked sufficient flying range for Atlantic crossings. Foynes was the last port of call on its eastern shore for seaplanes. As a result, Foynes would become one of the biggest civilian airports in Europe during World War II. Surveying flights for flying boat operations were made by Charles Lindbergh in 1933 and a terminal was begun in 1935.[2] The first transatlantic proving flights were operated on 5 July 1937 with a Pan Am Sikorsky S-42 service from Botwood, Newfoundland and Labrador on the Bay of Exploits and a BOAC Short Empire service from Foynes with successful transits of twelve and fifteen-and-a-quarter hours respectively. Services to New York, Southampton, Montreal, Poole and Lisbon followed, the first non-stop New York service operating on 22 June 1942 in 25 hours 40 minutes. All of this changed following the construction and opening in 1942 of Shannon Airport on flat bogland on the northern bank of the Estuary. Foynes flying-boat station closed in 1946.

Sea

Originally Limerick port was located near the confluence of the Abbey and Shannon rivers at King's Island. Today the port is located further downstream on the Shannon alongside the Dock Road and is operated by the Shannon Foynes Port Company (SFPC) who operate all marine activities in the Shannon estuary. It is a general purpose facility port. Plans to close the port and relocate all activity to the deepwater facility further downstream at Foynes have been abandoned. The plans included a major regeneration of the dockland area. Foynes is the main deepwater commercial port. SFPC is the second largest port facility in Ireland, handling over 10 million tonnes of cargo annually through the six terminals currently operational.

Sport

Limerick is widely regarded to be the Irish "spiritual" home of Rugby union,[13] which is very popular in the county, especially around Limerick city, which boasts many of Ireland's most celebrated All-Ireland League teams; Garryowen, Shannon, Old Crescent, Young Munster and UL Bohemians are among the most prominent. Limerick's Thomond Park is the home of the Munster Rugby team, who enjoy enthusiastic and often fanatical support throughout the county.

In the county, however, it is the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) which has the upper hand. Hurling in particular is strong in east, mid and south Limerick. Limerick GAA play their home games at the Gaelic Grounds in Limerick City. They have won the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship eight times, the last in 2018. The county has also won 20 Munster Championships, last in 2019 and 12 National Hurling Leagues, the last success coming in 2019. The Limerick Senior Hurling Championship is also one of the strongest club championships in the country. Historically it has been dominated by two clubs, Ahane and Patrickswell. Clubs from the county have won the Munster Senior Club Championship six times, with becoming the first team from the county to win the All-Ireland Senior Club hurling final when they beat Cushendall of Antrim 2–25 to 2–14 on 17 March 2016.

The other GAA sport of Gaelic football is more popular in west Limerick, particularly along the Shannon Estuary west of Askeaton and along the Kerry border. There are also football strongholds in the southeast of the county and on the eastern edges of the city. Although one of the strongest teams in the country during the early years of the GAA, the game in the county was overshadowed by hurling throughout the 20th century and its last success in the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship, the Sam Maguire Trophy, was in 1896. However, Limerick footballers have seen a reversal of fortunes in recent years and contested successive Munster Senior Football Championship finals in 2003 and 2004.

Limerick FC play in the FAI Premier Division, the first tier of Irish soccer. The club has won the Premier Division twice in 1960 and 1980. They have also won the FAI Cup twice in 1971 and 1982. They currently play in the Markets Field.

The city also has one of Ireland's two 50-metre (55 yd) swimming pools, at the University of Limerick Sports Arena, as well as one of Ireland's top basketball teams, the UL Eagles. The team plays in the Irish Premier League. Their home is also at the University Campus.

Limerick is also the hometown of WBO World Middleweight boxing Champion Andy Lee, who defeated Matt Korobov on 13 December 2014, in Las Vegas. He became the first Irishman to win a world title on American soil since 1934.

Media

Broadcasting

RTÉ Lyric FM, a state-run classical music radio station and part of RTÉ, broadcasts nationally from studios in Limerick city centre. Limerick's local radio station is Live 95FM, broadcasting from 'Radio House', near the waterfront at Steamboat Quay. Spin Southwest, owned by Communicorp, broadcasts to Counties Kerry, Clare, Limerick, Tipperary and southwest Laois from its studios at Landmark Buildings in the Raheen Industrial Estate. West Limerick 102 is broadcast from Newcastle West and is a community station for the west of the county. The national broadcaster, RTÉ, has radio studios in the city, which are periodically used to broadcast programming from Limerick.

Print

The two main newspapers that service the city and county are the Limerick Leader and the freesheet Limerick Post. The Limerick Leader prints three different editions: City, County and West Limerick. The Limerick Chronicle is owned by the Leader and is primarily a city paper. The Weekly Observer serves the western half of the county while the Vale Star covers South Limerick and North Cork.

TV

Irish TV, a local TV station, covers Limerick stories with its programme Limerick County Matters which goes out once a week.

Anthem

The song "Limerick you're a lady" is traditionally associated with the county. It is often heard at sports fixtures involving the county.[14] Seán South from Garryowen is another popular Limerick song and tells the account of the death of Limerick IRA member Sean South, who was killed during an attack on a Royal Ulster Constabulary barracks in County Fermanagh in 1957

See also

References

- "History of Limerick on Roots Ireland – Roots Ireland". www.rootsireland.ie.

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: County Limerick City And County". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Limerick City And Suburbs". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- For 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years, Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy 14 March 1865.

- "Server Error 404 - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie.

- Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- "Local authorities". citizensinformation.ie.

- "Report on Dáil and European Parliament Constituencies 2007" (PDF). Constituency Commission. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- "Oideachas Trí Mheán na Gaeilge in Éirinn sa Ghalltacht 2010–2011" (PDF) (in Irish). gaelscoileanna.ie. 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Rugby, Limerick". VirtualTourist.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for County Limerick. |

- Limerick's Official Tourist Website

- Limerick City and County Council

- County Limerick at Connors Genealogy