Romanian alphabet

The Romanian alphabet is a variant of the Latin alphabet used for writing the Romanian language. It is a modification of the classical Latin alphabet and consists of 31 letters,[1][2] five of which (Ă, Â, Î, Ș, and Ț) have been modified from their Latin originals for the phonetic requirements of the language:

| Letter | Name |

|---|---|

| A, a | a |

| Ă, ă | ă |

| Â, â | î / î din a |

| B, b | be / bî |

| C, c | ce / cî |

| D, d | de / dî |

| E, e | e |

| F, f | ef / fe / fî |

| G, g | ge / ghe / gî |

| H, h | haș / ha / hî |

| I, i | i |

| Letter | Name |

|---|---|

| Î, î | î / î din i |

| J, j | je / jî |

| K, k | ca / capa |

| L, l | el / le / lî |

| M, m | em / me / mî |

| N, n | en / ne / nî |

| O, o | o |

| P, p | pe / pî |

| Q, q | chiu (/ky/) |

| R, r | er / re / rî |

| S, s | es / se / sî |

| Letter | Name |

|---|---|

| Ș, ș | șe / șî |

| T, t | te / tî |

| Ț, ț | țe / țî |

| U, u | u |

| V, v | ve / vî |

| W, w | dublu ve / dublu vî |

| X, x | ics |

| Y, y | igrec / i grec |

| Z, z | ze / zet / zed / zî |

The letters Q (chiu), W (dublu v), and Y (igrec or i grec) were formally introduced in the Romanian alphabet in 1982, although they had been used earlier. They occur only in foreign words and their Romanian derivatives, such as quasar, watt, and yacht. The letter K, although relatively older, is also rarely used and appears only in proper names and international neologisms such as kilogram, broker, karate.[3] These four letters are still perceived as foreign, which explains their usage for stylistic purposes in words such as nomenklatură (normally nomenclatură, meaning "nomenclature", but sometimes spelled with k instead of c if referring to members of the Communist leadership in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries, as Nomenklatura is used in English).[4]

In cases where the word is a direct borrowing having diacritical marks not present in the above alphabet, official spelling tends to favor their use (München, Angoulême etc., as opposed to the use of Istanbul over İstanbul).

Letters and their pronunciation[5]

Romanian spelling is mostly phonemic without silent letters (but see i). The table below gives the correspondence between letters and sounds. Some of the letters have several possible readings, even if allophones are not taken into account. When vowels /i/, /u/, /e/, and /o/ are changed into their corresponding semivowels, this is not marked in writing. Letters K, Q, W, and Y appear only in foreign borrowings; the pronunciation of W and Y and of the combination QU depends on the origin of the word they appear in.

| Letter | Phoneme[6] | Approximate pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| A a | /a/ | a in "father" |

| Ă ă (a with breve) | /ə/ | a in "above" |

| Â â (a with circumflex) | /ɨ/ | the close central unrounded vowel as heard, for example, in the last syllable of the word roses for some English speakers |

| B b | /b/ | b in "ball" |

| C c | /k/ | c in "scan" |

| /tʃ/ | ch in "chimpanzee" — if c appears before letters e or i (but not î); in this case, e and i are usually not pronounced in the combinations: cea (cia in some loanwords), cio, ciu and in word-final ci if not accented | |

| D d | /d/ | d in "door" |

| E e | /e/ | e in "merry" |

| /e̯/, /ɛ̯/ | before a or o — semivocalic /e/; if not preceded by a consonant becomes /j/ | |

| /je/, /jɛ/ | ye in "yes" — in a few old words with initial e: este, el etc.[7] | |

| F f | /f/ | f in "flag" |

| G g | /ɡ/ | g in "goat" |

| /dʒ/ | g in "general" — if g appears before letters e or i (but not î); in this case, e and i are usually not pronounced in the combinations: gea (gia in some loanwords), gio (geo in some loanwords), giu and in word-final gi if not accented | |

| H h | /h/ ([h], [ç], [x]) | ch in Scottish "loch" or h in English "ha!" or more usually a subtle mix of the two (that is, not so guttural as the Scottish loch.) |

| (mute) | no pronunciation if h appears between letters c or g and e or i (che, chi, ghe, ghi); c and g are palatalized | |

| I i | /i/ | i in "machine" |

| /j/ | y in "yes" | |

| /ʲ/ | Indicates palatalization of the preceding consonant (when word-final and unstressed, in some compounds like oricum, and in the combinations chia, chio, chiu, ghia, ghio, ghiu) | |

| Î î (i with circumflex) | /ɨ/ | Identical to Â, see above, used at the beginning and at the end of the word for aesthetic reasons, ex. "to learn" = "a învăța"; "to kill" = "a omorî" |

| J j | /ʒ/ | s in "treasure" |

| K k | /k/ | c in "scan" (palatalized before e and i) |

| L l | /l/ | l in "limp" |

| M m | /m/ | m in "mouth" |

| N n | /n/ | n in "north" |

| O o | /o/ | o in "floor" |

| /o̯/, /ɔ̯/ | before a — semivocalic /o/; if not preceded by a consonant becomes /w/ | |

| P p | /p/ | p in "spot" |

| Q q | /k/ | k in "kettle" (qu is pronounced /kw/, /kv/, or /kʲ/) |

| R r | /r/ | alveolar trill or tap |

| S s | /s/ | s in "song" |

| Ș ș (s with comma) * | /ʃ/ | sh in "shopping" |

| T t | /t/ | t in "stone" |

| Ț ț (t with comma) * | /ts/ | zz in "pizza" but with considerable emphasis on the "ss" |

| U u | /u/ | u in "group" |

| /w/ | w in "cow" | |

| /y/ | French u or German ü (close front rounded vowel) — in some loanwords from French: ecru, tul | |

| V v | /v/ | v in "vision" |

| W w | /v/ | v in "vision" |

| /w/ | w in "west" | |

| /u/ | oo in "spoon" | |

| X x | /ks/ | x in "six" |

| /ɡz/ | x in "example" | |

| Y y | /j/ | y in "yes" |

| /i/ | i in "machine" | |

| Z z | /z/ | z in "zipper" |

Special letters

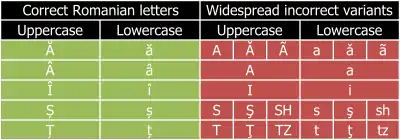

Romanian orthography does not use accents or diacritics – these are secondary symbols added to letters (i.e. basic glyphs) to alter their pronunciation or to distinguish between words. There are, however, five special letters in the Romanian alphabet (associated with four different sounds) which are formed by modifying other Latin letters; strictly speaking these letters function as basic glyphs in their own right rather than letters with diacritical marks, but they are often referred to as the latter.

- Ă ă — a with breve – for the sound /ə/

- Â â — a with circumflex – for the sound /ɨ/

- Î î — i with circumflex – for the sound /ɨ/

- Ș ș — s with comma – for the sound /ʃ/

- Ț ț — t with comma – for the sound /t͡s/

The letter â is used exclusively in the middle of words; its majuscule version appears only in all-capitals inscriptions.

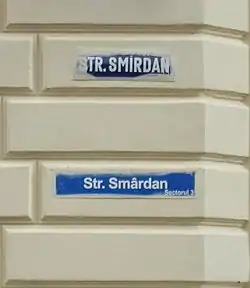

Writing letters ș and ț with a cedilla instead of a comma is considered incorrect by the Romanian Academy. Romanian writings, including books created to teach children to write, treat the comma and cedilla as a variation in font. See Unicode and HTML below.

Î versus Â

The letters î and â are phonetically and functionally identical. The reason for using both of them is historical, denoting the language's Latin origin.

For a few decades until a spelling reform in 1904, as many as four or five letters had been used for the same phoneme (â, ê, î, û, and occasionally ô), according to an etymological rule.[8] All were used to represent the vowel /ɨ/, toward which the original Latin vowels written with circumflexes had converged. The 1904 reform saw only two letters remaining, â and î, the choice of which followed rules that changed several times during the 20th century.

During the first half of the century the rule was to use î in word-initial and word-final positions, and â everywhere else. There were exceptions, imposing the use of î in internal positions when words were combined or derived with prefixes or suffixes. For example, the adjective urît "ugly" was written with î because it derives from the verb a urî "to hate".

In 1953, during the Communist era, the Romanian Academy eliminated the letter â, replacing it with î everywhere, including the name of the country, which was to be spelled Romînia. The first stipulation coincided with the official designation of the country as a People's Republic, which meant that its full title was Republica Populară Romînă. A minor spelling reform in 1964 brought back the letter â, but only in the spelling of român "Romanian" and all its derivatives, including the name of the country. As such, the Socialist Republic proclaimed in 1965 is associated with the spelling Republica Socialistă România.

Soon after the fall of the Ceaușescu government, the Romanian Academy decided to reintroduce â from 1993 onward, by canceling the effects of the 1953 spelling reform and essentially reverting to the 1904 rules (with some differences). The move was publicly justified as the rectification either of a Communist assault on tradition, or of a Soviet influence on the Romanian culture, and as a return to a traditional spelling that bears the mark of the language's Latin origin.[9][10][11] The political context at the time, however, was that the Romanian Academy was largely regarded as a Communist and corrupt institution — Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena had been its honored members, and membership had been controlled by the Communist Party.[12] As such, the 1993 spelling reform was seen as an attempt of the Academy to break with its Communist past.[13][14] The Academy invited the national community of linguists as well as foreign linguists specialized in Romanian to discuss the problem;[15] when these overwhelmingly opposed the spelling reform in vehement terms, their position was explicitly dismissed as being too scientific.[16][17]

According to the 1993 reform, the choice between î and â is thus again based on a rule that is neither strictly etymological nor phonological, but positional and morphological. The sound is always spelled as â, except at the beginning and the end of words, where î is to be used instead. Exceptions include proper nouns where the usage of the letters is frozen, whichever it may be, and compound words, whose components are each separately subjected to the rule (e.g. ne- + îndemânatic → neîndemânatic "clumsy", not *neândemânatic). However, the exception no longer applies to words derived with suffixes, in contrast with the 1904 norm; for instance what was spelled urît after 1904 became urât after 1993.

Although the reform was promoted as a means to show the Latin origin of Romanian, statistically only few of the words written with â according to the 1993 reform actually derive from Latin words having an a in the corresponding position.[18] In fact, this includes a large number of words that contained an i in the original Latin and are similarly written with i in their Italian or Spanish counterparts. Examples include rîu "river", from the Latin rivus (compare Spanish río), now written râu; along with rîde < ridere, sîn < sinus, strînge < stringere, lumînare < luminaria, etc.

While the 1993 spelling norm is compulsory in Romanian education and official publications, and gradually most other publications came to use it, there are still individuals, publications and publishing houses preferring the previous spelling norm or a mixed hybrid system of their own. Among them are the weekly cultural magazine Dilema Veche and the daily Gazeta Sporturilor, whereas some publications allow authors to choose either spelling norm; these include România literară, magazine of the Writers' Union of Romania, and publishing houses such as Polirom. Dictionaries, grammars and other linguistic works have also been published using the î and sînt long after the 1993 reform.[19]

Ultimately, the conflict results from two different linguistically-based reasonings as to how to spell /ɨ/. The choice of â derives from a being the most average or central of the five vowels (the official Bulgarian romanization uses the same logic, choosing a for ъ, resulting in the country's name being spelled Balgariya; and also the European Portuguese vowel /ɐ/ for a mentioned above), whereas î is an attempt to choose the Latin letter that most intuitively writes the sound /ɨ/ (similarly to how Polish uses the letter y).

Comma-below (ș and ț) versus cedilla (ş and ţ)

Although the Romanian Academy standard mandates the comma-below variants for the sounds /ʃ/ and /t͡s/, the cedilla variants are still widely used. Many printed and online texts still incorrectly use "s with cedilla" and "t with cedilla". This state of affairs is due to an initial lack of glyph standardization, compounded by the lack of computer font support for the comma-below variants (see the Unicode section for details).

The lack of support for the comma diacritics has been corrected in current versions of major operating systems: Windows Vista or newer, Linux distributions after 2005, and currently supported Mac OS versions. As mandated by the European Union, Microsoft released a font update to correct this deficiency in Windows XP in early 2007, soon after Romania joined the European Union.

Obsolete letters

Before the spelling reform of 1904, there were several additional letters with diacritical marks.

- Vowels:

- ĭ — i with breve indicated semivowel i as part of Romanian diphthongs and triphthongs ia, ei, iei etc., or a final, "whispered" sound of the preceding palatalized consonant, in words such as București (/bu.kuˈreʃtʲ/), lupi (/lupʲ/ – "wolves"), and greci (/ɡret͡ʃʲ/ – "Greeks") — Bucurescĭ (the proper spelling at the time used c instead of t, see -ești), lupĭ, grecĭ, like the Slavonic soft sign. The Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet kept the Cyrillic equivalents of this letter, namely й and ь, but it was abolished in the Romanian Latin alphabet for unknown reasons. By replacing this letter with a simple i without making any additional changes, the phonetic value of the letter i became ambiguous; even native speakers can sometimes mispronounce words such as the toponym Pecica (which has two syllables, but is often mistakenly pronounced with three) or the name Mavrogheni (which has four syllables, not three).[20] Additionally, in a number of words such as subiect "subject"[21] and ziar "newspaper",[22] the pronunciation of i as a vowel or as a semivowel is different among speakers.

- ŭ — u with breve was used only in the ending of a word. It was essentially a Latin equivalent of the Slavonic back yer found in languages like Russian. Unpronounced in most cases, it served to indicate that the previous consonant was not palatalized, or that the preceding i was the vowel [i] and not a mere marker of palatalization. When ŭ was pronounced, it would follow a stressed vowel and stand in for semivowel u, as in words eŭ, aŭ, and meŭ, all spelled today without the breve. Once frequent, it survives today in author Mateiu Caragiale's name – originally spelled Mateiŭ (it is not specified whether the pronunciation should adopt a version that he himself probably never used, while in many editions he is still credited as Matei). In other names, only the breve was dropped, while preserving the pronunciation of a semivowel u, as is the case of B.P. Hasdeŭ.

- ĕ — e with breve. This letter is now replaced with ă. The existence of two letters for one sound, the schwa, had an etymological purpose, showing from which vowel ("a" or "e") it originally derived. For example împĕrat – "emperor" (<Imperator), vĕd – "I see" (<vedo), umĕr – "shoulder" (<humerus), păsĕri – "birds" (<cf. passer).

- é / É — Latin small/capital letter e with acute accent indicated a sound that corresponds either to today's Romanian diphthong ea, or in some words, to today's Romanian letter e. It would originally indicate the sound of Romanian letter e when it was pronounced as diphthong ea in certain Romanian regions, e.g. acéste (today spelled aceste) and céle (today spelled cele). This letter would sometimes indicate a derived word from a Romanian root word containing Latin letter e, as is the case of mirésă (today spelled mireasă) derived from mire. For other words it would underlie a relationship between a Romanian word and a Latin word containing letter e, where the Romanian word would use é, such as gréle (today spelled grele) derived from Latin word grevis. Lastly, this letter was used to accommodate the sound that corresponds to today's Romanian diphthong ia, as in the word ér (iar today).

- ó / Ó — Latin small/capital letter o with acute accent indicated a sound that corresponds to today's Romanian diphthong oa. This letter would sometimes indicate a derived word from a Romanian root word containing Latin letter o, as is the case of popóre (today spelled popoare) derived from popor. For other words it would underlie a relationship between a Romanian word and a Latin word containing letter o, where the Romanian word would use ó, such as fórte (today spelled foarte) derived from Latin word forte. Lastly, this letter was used to accommodate the sound that corresponds to today's Romanian diphthong oa, as in the word fóme (foame today).

- ê, û and ô — see Î versus  section above.

- Consonants

- d̦ / D̦ — Latin small/capital letter d with comma below was used to indicate the sound that corresponds today to Romanian letter z. It would denote that the word it belonged to derived from Latin and that its corresponding Latin letter was d. Examples of words containing this letter are: d̦ece ("ten"), d̦i ("day") – reflecting its derivation[23] from the Latin word dies, Dumned̦eu ("God") – reflecting[24] the Latin phrase Domine Deus, d̦ână ("fairy")[25] – to be derived from the Latin word Diana. In today's Romanian language this letter is no longer present and Latin letter z is used in its stead. A parallel development has occurred in Polish, which turned d before a front vowel (i or e) into dz; Romanian then removed the d to leave the z.

Use of these letters was not fully adopted even before 1904, as some publications (e.g. Timpul and Universul) chose to use a simplified approach that resembled today's Romanian language writing.

Other diacritics

As with other languages, the acute accent is sometimes used in Romanian texts to indicate the stressed vowel in some words. This use is regular in dictionary headwords, but also occasionally found in carefully edited texts to disambiguate between homographs that are not also homophones, such as to differentiate between cópii ("copies") and copíi ("children"), éra ("the era") and erá ("was"), ácele ("the needles") and acéle ("those"), etc. The accent also distinguishes between homographic verb forms, such as încúie and încuié ("he locks" and "he has locked").[26]

Diacritics in some borrowings are kept: bourrée, pietà. Foreign names are also usually spelled with their original diacritics: Bâle, Molière, even when an acute accent might be wrongly interpreted as a stress, as in István or Gérard. However, frequently used foreign names, such as names of cities or countries, are often spelled without diacritics: Bogota, Panama, Peru.[27]

Digital typography

ISO 8859

The character encoding standard ISO 8859 initially defined a single code page for the entire Central and Eastern Europe — ISO 8859-2. This code page includes only "s" and "t" with cedillas. The South-Eastern European ISO 8859-16 includes "s" and "t" with comma below on the same places "s" and "t" with cedilla were in ISO 8859-2. The ISO 8859-16 code page became a standard after Unicode became widespread, however, so it was largely ignored by software vendors.

Unicode and HTML

The circumflex and breve accented Romanian letters were part of the Unicode standard since its inception, as well as the cedilla variants of s and t. Ș and ț (comma-below variants) were added to Unicode version 3.0.[28][29] From Unicode version 3.0 to version 5.1, the cedilla-using characters were specified by the Unicode Standard to be "used in both Turkish and Romanian data" and that "a glyph variant with comma below is preferred for Romanian"; On the newly encoded comma-using characters, it said that they should be used "when distinct comma below form is required".[30][31] Unicode 5.2 explicitly states that "the form with the cedilla is preferred in Turkish, and the form with the comma below is preferred in Romanian", while mentioning (possibly for historical reasons) that "in Turkish and Romanian, a cedilla and a comma below sometimes replace one another".[32]

Widespread adoption was hampered for some years by the lack of fonts providing the new glyphs. In May 2007, five months after Romania (and Bulgaria) joined the EU, Microsoft released updated fonts that include all official glyphs of the Romanian (and Bulgarian) alphabet.[33] This font update targeted Windows XP SP2, Windows Server 2003, and Windows Vista. The subset of Unicode most widely supported on Microsoft Windows systems, Windows Glyph List 4, still does not include the comma-below variants of S and T.

| Phoneme | With comma (official) | With cedilla | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character | Unicode position (hex) |

HTML entity | Character | Unicode position (hex) |

HTML entity | |

| /ʃ/ | Ș | 0218 | Ș or Ș | Ş | 015E | Ş or Ş or Ş |

| ș | 0219 | ș or ș | ş | 015F | ş or ş or ş | |

| /t͡s/ | Ț | 021A | Ț or Ț | Ţ | 0162 | Ţ or Ţ or Ţ |

| ț | 021B | ț or ț | ţ | 0163 | ţ or ţ or ţ | |

Vowels with diacritics are coded as follows:

| Phoneme | Character | Unicode position (hex) |

HTML entity |

|---|---|---|---|

| /ə/ | Ă | 0102 | Ă or Ă or Ă |

| ă | 0103 | ă or ă or ă | |

| /ɨ/ |  | 00C2 |  or  or  |

| â | 00E2 | â or â or â | |

| Î | 00CE | Î or Î or Î | |

| î | 00EE | î or î or î |

Adobe/Linotype/Vista de facto standard

GSUB/latn/ROM/locl feature, which remaps the s with cedilla glyph to comma-below. The rendering on the right is visually indistinguishable from the rendering produced by comma-below code points for this font.Adobe Systems decided[34] that the Unicode glyphs "t with cedilla" U+0162/3 are not used in any language. (It is in fact used, but in very few languages. T with Cedilla exists as part of the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages, in some Gagauz orthographies, in the Kabyle dialect of the Berber language, and possibly elsewhere.) Adobe has therefore substituted the glyphs with "t with comma below" (U+021A/B) in all the fonts they ship. The unfortunate consequence of this decision is that Romanian documents using the (unofficial) Unicode points U+015E/F and U+0162/3 (for ș and ț) are rendered in Adobe fonts in a visually inconsistent way using "s with cedilla", but "t with comma" (see figure). Linotype fonts that support Romanian glyphs mostly follow this convention.[35]

The fonts introduced by Microsoft in Windows Vista also implement this de facto Adobe standard. Few Microsoft fonts provide a consistent look when cedilla variants are used; notable ones are Tahoma, Verdana, Trebuchet MS, Microsoft Sans Serif and Segoe UI.

The free DejaVu and Linux Libertine fonts provide proper and consistent glyphs in both variants. Red Hat's Liberation fonts only support the comma below variants starting with version 1.04, scheduled for inclusion in Fedora 10.

OpenType ROM/locl feature

ROM/locl featureSome OpenType fonts from Adobe and all C-series Vista fonts implement the optional OpenType feature GSUB/latn/ROM/locl.[36] This feature forces "s with cedilla" to be rendered using the same glyph as "s with comma below". When this second (but optional) remapping takes place, Romanian Unicode text is rendered with comma-below glyphs regardless of code point variants.

Unfortunately, most Microsoft pre-Vista OpenType fonts (Arial etc.) do not implement the ROM/locl feature, even after the European Union Expansion Font Update,[33] so old documents will look inconsistent as in the left side of the above figure. Select few fonts, e.g. Verdana and Trebuchet MS, not only have a consistent look for cedilla variants (after the EU update), but also do a simultaneous remapping of cedilla s and t to comma-below variants when ROM/locl is activated. The free DejaVu and Linux Libertine fonts do not yet offer this feature in their current releases, but development versions do.

Pango supports the locl tag since version 1.17. XeTeX supports locl since version 0.995. As of July 2008, very few Windows applications support the locl feature tag. From the Adobe CS3 suite, only InDesign has support for it.[37]

The status of Romanian support in the free fonts that ship with Fedora is maintained at Fedoraproject.org.

Combining characters

Unicode also allows diacritical marks to be represented as separate combining diacritical marks. The relevant combining accents are U+0326 COMBINING COMMA BELOW and U+0327 COMBINING CEDILLA. Support for applying a combining Comma Below to letters S and T may have been poorly supported in commercial fonts in the past, but nearly all modern fonts can successfully handle both the Cedilla and Comma Below marks for S and T. As with all fonts, typographical quality can vary, and so it is preferable to use the single code points instead. Whenever a combining diacritical mark is used in a document, the font in use should be tested to confirm that it is rendered acceptably.

(La)TeX

LaTeX allows typesetting in Romanian using the cedilla Ş and Ţ using the Cork encoding. The comma-below variants are not completely supported in the standard 8-bit TeX font encodings. The lack of a standard LICR (LaTeX Internal Character Representations) for comma-below Ș and Ț is part of the problem. The latin10 input method attempts to remedy the problem by defining the \textcommabelow LICR accent. This is unfortunately not supported by the utf8 input method.

The problem may partially worked around in a LaTeX document using these settings, which would allow use of ș, ț or their cedilla variants directly in the LaTeX source:

\usepackage[latin10,utf8]{inputenc}

% transliterates utf8 chars with çedila at their comma-below representation

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{015F}{\textcommabelow s} % ş

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{015E}{\textcommabelow S} % Ş

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{0163}{\textcommabelow t} % ţ

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{0162}{\textcommabelow T} % Ţ

% transliterates utf8 comma-below characters to the comma-below representation

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{0219}{\textcommabelow s} % ș

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{0218}{\textcommabelow S} % Ș

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{021B}{\textcommabelow t} % ț

\DeclareUnicodeCharacter{021A}{\textcommabelow T} % Ț

The latin10 package composes the comma-below glyphs by superimposing a comma and the letters S and T. This method is suitable only for printing. In PDF documents produced this way searching or copying text does not work properly. The Polish QX encoding has some support for comma-below glyphs, which are improperly mapped to cedilla LICRs, but also lacks A breve (Ă), which must always be composite, thus unsearchable.

In the Latin Modern Type 1 fonts the T with comma below is found under the AGL name /Tcommaaccent. This is in contradiction with Adobe's decision discussed above, which puts a T with comma-below at /Tcedilla. In consequence, no fixed mapping can work across all Type 1 fonts; each font must come with its own mapping. Unfortunately, TeX output drivers, like dvips, dvipdfm or pdfTeX's internal PDF driver, access the glyphs by AGL name. Since all of the output drivers mentioned are unaware of this peculiarity, the problem is essentially intractable across all fonts. In consequence, one needs to use fonts that include a mapping which is not bypassed by TeX. This is the case with newer TeX engine XeTeX, which can use Unicode OpenType fonts, and does not bypass the font's Unicode map.

Keyboard layout

Modern computer operating systems can be configured to implement a standard Romanian keyboard layout, to permit typing on any keyboard as if it were a Romanian keyboard.

In systems such as GNU/Linux which employ the XCompose system, Romanian letters may be typed from a non-Romanian keyboard layout using a compose-key. The system's keyboard layout must be set up to use a compose-key. (Exactly how this is accomplished depends on the distribution.) For instance, the 'left Alt' key is often used as a compose-key.

To type a letter with a diacritical mark, the compose-key is held down while another key is typed indicate the mark to be applied, then the base letter is typed. For instance, when using an English (US) keyboard layout, to produce ț, hold the compose-key down while typing semicolon ';', then release the compose-key and type 't'. Other marks may be similarly applied as follows:

| letter | mark key | base letter | note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ț | ; | t | |

| ă | U | a | shift-u for U |

| î | ^ | i | shift-6 for ^ |

Phonetic alphabet

There is a Romanian equivalent to the English-language NATO phonetic alphabet. Most code words are people's first names, with the exception of K, J, Q, W and Y. Letters with diacritics (Ă, Â, Î, Ș, Ț) are generally transmitted without diacritics (A, A, I, S, T).

| Word | IPA (unofficial) | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Ana | /ˈa.na/ |

| B | Barbu | /ˈbar.bu/ |

| C | Constantin | /kon.stanˈtin/ |

| D | Dumitru | /duˈmi.tru/ |

| E | Elena | /eˈle.na/ |

| F | Florea | /ˈflo.re̯a/ |

| G | Gheorghe | /ˈɡe̯or.ɡe/ |

| H | Haralambie | /ha.raˈlam.bi.e/ |

| I | Ion | /iˈon/ |

| J | Jiu | /ʒiw/ |

| K | kilogram | /ki.loˈɡram/ |

| L | Lazăr | /ˈla.zər/ |

| M | Maria | /maˈri.a/ |

| Word | IPA (unofficial) | |

|---|---|---|

| N | Nicolae | /ni.koˈla.e/ |

| O | Olga | /ˈol.ɡa/ |

| P | Petre | /ˈpe.tre/ |

| Q | Q | /kju/ |

| R | Radu | /ˈra.du/ |

| S | Sandu | /ˈsan.du/ |

| T | Tudor | /ˈtu.dor/ |

| U | Udrea | /ˈu.dre̯a/ |

| V | Vasile | /vaˈsi.le/ |

| W | dublu V | /du.bluˈve/ |

| X | Xenia | /ˈkse.ni.a/ |

| Y | I grec | /ˈi.ɡrek/ |

| Z | Zamfir | /ˈzam.fir/ |

References

Notes

- (in Romanian) Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române, 1998, Z is the thirty first letter of the Romanian alphabet, dexonline.ro

- Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică „Iorgu Iordan – Al. Rosetti", Dicționarul ortografic, ortoepic și morfologic al limbii române, Editura Univers Enciclopedic, București, 2005, pp. XXVII–XXVIII (in Romanian)

- (in Romanian) Academia Română, Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române, Entry for K, Editura Univers Enciclopedic, 1998, dexonline.ro

- Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică „Iorgu Iordan – Al. Rosetti", Dicționarul ortografic, ortoepic și morfologic al limbii române, 2nd Edition, Univers Enciclopedic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2005, ISBN 973-637-087-9, p. XXIX (in Romanian)

- Academia Română, Institutul de Lingvistică „Iorgu Iordan – Al. Rosetti", Dicționarul ortografic, ortoepic și morfologic al limbii române, 2nd Edition, Univers Enciclopedic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2005, ISBN 973-637-087-9, p. XXIX–XXXVI (in Romanian)

- Ovidiu Drăghici. "Limba Română contemporană. Fonetică. Fonologie. Ortografie. Lexicologie" (PDF). Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- (in Romanian) Several Romanian dictionaries specify the pronunciation [je] for word-initial letter e in some personal pronouns: el, ei, etc. and in some forms of the verb a fi (to be): este, eram, etc.

- Alf Lombard, "Despre folosirea literelor â și î", Limba română, 1992, №10, p. 531

- Dumitru Irimia, "De ce scriu și susțin scrierea cu î din i?" (in Romanian) "In its rationale report for the 'new' orthography, presented in 1992, the Romanian Academy considered that it had the 'duty to cut out a bridgehead in the Romanian language,' placed there by the occupier and the Communist power. 'The 1953 orthography is Stalinist,' we were told repeatedly and we are told now again. Two things are true: (1) The 1953/1965 orthography was established during the Communist regime. (2) The orthographic system was preceded by a 'framework', a panegyrical Stalinist introduction. That is all."

- Mioara Avram, "Patrioticul â", Expres Magazin, №24 (150), 23–30 June 1993, p. 20 (in Romanian) "In January 1993, the leadership of the Academy took the initiative in changing the orthography, presenting from the beginning this measure as an act of reparation brought to the Romanian language for the alleged totalitarian assault upon it by the Communist regime."

- Alex. Ștefănescu, "De ce scriu cu â din a", România literară, №38, 2002 (in Romanian) "I write using â for yet another reason: because by doing so I want to contest, every day, a spelling norm that was established abusively during Stalinism. Established not on linguistic grounds, but on political grounds. By giving up the letter â, they were pulling out, as with tweezers, the Latin nerve from the Romanian language."

- "Victime de elită", Evenimentul zilei, 4 February 2006 (in Romanian) "In 1974, Elena Ceaușescu became full member of the Academy of the Socialist Republic of Romania. It was the conclusion of a process that had begun a few years earlier, by which the Academy, an institution with a history of over 100 years at that point, was entirely subordinated to the Party. In 1985, her husband was to become himself a full member as well as the honorary president of the Academy."

- Ion Bogdan Lefter (2001). "Limba romana speculata politic".

- George Pruteanu, "Â-ul fără noimă", Expres Magazin, №10 (238), 14–21 March 1995, p. 14 (in Romanian) "Through such a politicizing justification, the Academy was attempting to atone, in a seemingly spectacular gesture, its heavy sins of flattery and obedience toward the Communist Party, during the dictatorship years, the diluting of its membership with all sorts of worthless intruders who are otherwise still among the 'eternals'."

- Acozmei, Constantin, ed. (2018). 100 de ani de grafie românească. ISBN 978-606-94358-1-6.

- Elis Râpeanu (2018). "cum a fost votată, în cadrul academiei române, revenirea la scrierea cu â și î".

- Ștefan Cazimir, "Dragă Academie", România literară, №5, 2003 (in Romanian)

- A statistical study cited by George Pruteanu in "De ce scriu cu î din i" ("Why I spell with î") finds that proportion to be only about 15%.

- For instance: Eugenia Dima et al., Dicționar explicativ ilustrat al limbii române, 2007; Ioan Oprea et al., Noul dicționar universal al limbii române, third edition, 2008; Dumitru Irimia, Gramatica limbii române, third edition, 2008.

- (in Romanian) Mioara Avram, Ortografie pentru toți, Editura Litera Internațional, București – Chișinău, 2002, p. 66

- Most dictionaries give the syllabification su-biect, implying that i is a semivowel, but Dicționar de neologisme syllabifies it as su-bi-ect, with vocalic i: Dexonline.ro

- Dictionaries generally recommend the pronunciation with vocalic i, zi-ar, but the pronunciation in one syllable is also recorded, among others, by Ioana Chițoran, in The Phonology of Romanian, 2002, p. 14.

- Definition of Romanian word zi at dexonline.ro

- Definition of Romanian word Dumnezeu at dexonline.ro

- Definition of Romanian word zână at dexonline.ro

- Dicționarul ortografic, ortoepic și morfologic al limbii române, 2005, p. LI (in Romanian)

- Dicționarul ortografic, ortoepic și morfologic al limbii române, 2005, p. LII (in Romanian)

- Unicode 3.0 standard, p.162

- Unicode.org

- Unicode.org

- Unicode.org

- Unicode 5.2 Chapter 7, European Alphabetic Scripts

- European Union Expansion Font Update, microsoft.com

- comments of Canadian type designer John Hudson, typophile.com

- Linotype's font finder allows users to test font rendering with their own sample texts. Tested with the sample text "Țâșnit în şanţ".Linotype.com

-

loclglyph localization feature tag explained., microsoft.com - p. 15, store.adobe.com

Bibliography

- (in Romanian) Mioara Avram, Ortografie pentru toți, Editura Litera Internațional, 2002

- The Unicode Consortium (2000). The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-61633-5.

External links

- Unicode Latin Extended-B characters, unicode.org

- Sounds of the Romanian Language, etc.tuiasi.ro