Psicose

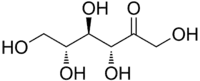

D-Psicose (C6H12O6), also known as D-allulose, or simply allulose, is a low-calorie monosaccharide sugar used by some major commercial food and beverage manufacturers.[2] First identified in wheat more than 70 years ago, allulose is naturally present in small quantities in certain foods.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(3R,4R,5R)-1,3,4,5,6-Pentahydroxyhexan-2-one | |

| Other names

D-Allulose; D-Psicose; D-Ribo-2-hexulose; Pseudofructose | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.182 |

| MeSH | psicose |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.156 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 58 °C (136 °F; 331 K) [1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Biochemistry

The sweetness of allulose is estimated to be 70% of the sweetness of sucrose.[3][4] It has some cooling sensation and no bitterness.[2] Its taste is said to be sugar-like, in contrast to certain other sweeteners, like the high-intensity artificial sweeteners aspartame and saccharine.[2] The caloric value of allulose in humans is about 0.2 to 0.4 kcal/g, relative to about 4 kcal/g for typical carbohydrates.[4][5] In rats, the relative energy value of allulose was found to be 0.007 kcal/g, or approximately 0.3% of that of sucrose.[6] Similar to the sugar alcohol erythritol, allulose is minimally metabolized and is excreted largely unchanged.[4] The glycemic index of allulose is very low or negligible.[2][4]

Allulose is a weak inhibitor of the enzymes α-glucosidase, α-amylase, maltase, and sucrase.[2] Because of this, it can inhibit the metabolism of starch and disaccharides into monosaccharides in the gastrointestinal tract.[2] Additionally, allulose inhibits the absorption of glucose via transporters in the intestines.[2] For these reasons, allulose has potential antihyperglycemic effects, and has been found to reduce postprandial hyperglycemia in humans.[2][5] Through modulation of lipogenic enzymes in the liver, allulose may also have antihyperlipidemic effects.[2][5]

Due to its effect of causing incomplete absorption of carbohydrates from the gastrointestinal tract, and subsequent fermentation of these carbohydrates by intestinal bacteria, allulose can result in unpleasant symptoms such as flatulence, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea.[2] The maximum non-effect dose of allulose in causing diarrhea in humans has been found to be 0.55 g/kg of body weight.[2] This is higher than that of most sugar alcohols (0.17–0.42 g/kg), but is less than that of erythritol (0.66–1.0+ g/kg).[7][8][9]

Chemistry

Allulose, also known by its systematic name D-ribo-2-hexulose as well as by the name D-psicose, is a monosaccharide and a ketohexose.[2][6] It is a C3 epimer of fructose.[2] Fructose can be converted to allulose by the enzyme D-tagatose 3-epimerase, which has allowed for mass production of allulose.[2] The compound is found naturally in trace amounts in wheat, figs, raisins, maple syrup, and molasses.[2][6][10] Allulose has similar physical properties to those of regular sugar, such as bulk, mouthfeel, browning capability, and freeze point.[10] This makes it favorable for use as a sugar replacement in food products, including ice cream.[10]

History

Allulose was first discovered in the 1940s.[10] The first mass-production method for allulose was established when Ken Izumori at Kagawa University in Japan discovered the key enzyme, D-tagatose 3-epimerase, to convert fructose to allulose in 1994.[11][12] This method of production has a high yield, but suffers from a very high production cost.

In June 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) accepted the assertion of CJ CheilJedang, Inc. that allulose is Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) as a sugar substitute in various specified food categories.[13]In June 2014, a similar GRAS letter was issued to Matustani Chemical Industry Company, Ltd.[14] First Non-GMO allulose was manufactured by Samyang Corporation.[15] Allulose is not approved for use in the European Union.

Oct 2019, FDA announced exemption of allulose from total and added sugars on nutritional label but adding 0.4kcal/g as carbohydrate.[16]

Studies have shown the commercial product is not absorbed in the human body the way common sugars are and does not raise insulin levels but more testing may be needed to evaluate any other potential side effects.[17]

Manufacturing

As of 2018, most commercially available allulose was produced from corn.[18] Alluose is also produced from beet sugar.[19]

Commercial application

Commercial manufacturers and food laboratories are looking into properties of allulose that may differentiate it from sucrose and fructose sweeteners, including an ability to induce the high foaming property of egg white protein and the production of antioxidant substances produced through the Maillard reaction.

Commercial uses of allulose include low-calorie sweeteners in beverages, yogurt, ice cream, baked goods, and other typically high-calorie items. London-based Tate & Lyle released its proprietary variant of allulose, known as Dolcia Prima allulose,[21] and U.S.-based Anderson Global Group released its own proprietary variant into the North American market in 2015.[22][23] The first major food company to adopt allulose as a sweetener was Quest Nutrition in some of their protein bar products.[10]

On April 16, 2019, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a draft guidance, allowing food manufacturers to exclude allulose from total and added sugar counts on Nutrition and Supplement Facts labels.[24] Like sugar alcohols and dietary fiber, allulose will still count towards total carbohydrates on nutrition labels.[24] This, combined with the GRAS designation, has increased interest in including allulose in food products instead of sucrose.

References

- Lide, David R.; Milne, G.W.A., eds. (30 Dec 1993). CRC Handbook of Data on Organic Compounds (3rd ed.). CRC Press. p. 4596.

- Hossain, Akram; Yamaguchi, Fuminori; Matsuo, Tatsuhiro; Tsukamoto, Ikuko; Toyoda, Yukiyasu; Ogawa, Masahiro; Nagata, Yasuo; Tokuda, Masaaki (2015). "Rare sugar d-allulose: Potential role and therapeutic monitoring in maintaining obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 155: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.08.004. ISSN 0163-7258.

- Chung, Min-Yu; Oh, Deok-Kun; Lee, Ki Won (1 Feb 2012). "Hypoglycemic health benefits of D-psicose". J Agric Food Chem. ACS. 60 (4): 863–869. doi:10.1021/jf204050w. PMID 22224918.

- Karl F. Tiefenbacher (16 May 2017). The Technology of Wafers and Waffles I: Operational Aspects. Elsevier Science. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-0-12-811452-0.

- Lê, Kim-Anne; Robin, Frédéric; Roger, Olivier (2016). "Sugar replacers". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 19 (4): 310–315. doi:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000288. ISSN 1363-1950.

- Mu, Wanmeng; Zhang, Wenli; Feng, Yinghui; Jiang, Bo; Zhou, Leon (2012). "Recent advances on applications and biotechnological production of d-psicose". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 94 (6): 1461–1467. doi:10.1007/s00253-012-4093-1. ISSN 0175-7598.

- Mäkinen, Kauko K. (2016). "Gastrointestinal Disturbances Associated with the Consumption of Sugar Alcohols with Special Consideration of Xylitol: Scientific Review and Instructions for Dentists and Other Health-Care Professionals". International Journal of Dentistry. 2016: 1–16. doi:10.1155/2016/5967907. ISSN 1687-8728.

- Kay O'Donnell; Malcolm Kearsley (13 July 2012). Sweeteners and Sugar Alternatives in Food Technology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 322–. ISBN 978-1-118-37397-2.

- Kathleen A. Meister; Marjorie E. Doyle (2009). Obesity and Food Technology. Am Cncl on Science, Health. pp. 14–. GGKEY:2Q64ACGKWRT.

- https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-allulose-sugar-substitute-20190822-ayfcmkmol5a33jziuoguubrt7i-story.html

- Itoh, Hiromichi; Okaya, Hiroaki; Khan, Anisur Rahman; et al. (1994). "Purification and characterization of D-tagatose 3-epimerase from Pseudomonas sp. ST-24". Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 58: 2168–2171. doi:10.1271/bbb.58.2168. Archived from the original on 2012-08-04.

- Itoh, Hiromichi; Sato, Tomoko; Izumori, Ken (1995). "Preparation of D-psicose from D-fructose by immobilized D-tagatose 3-epimerase". J Fermentation and Bioengineering. Elsevier B.V. 80 (1): 101–103. doi:10.1016/0922-338X(95)98186-O.

- "GRN No. 400". fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "GRN No. 498". FDA. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "GRAS Notice GRN 000828".

- "The Declaration of Allulose and Calories From Allulose on Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels; Availability". Federal Register. 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- Elejalde-Ruiz, Alexia (August 22, 2019). "A natural sweetener with a tenth of sugar's calories. Allulose, developed in Hoffman Estates, could be 'breakthrough ingredient.'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- A new way to make allulose may not sweeten the sugar's appeal

- "Allulose". Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Watson, Elaine (25 Feb 2015). "Tate & Lyle unveils Dolcia Prima allulose low-calorie-sugar: 'We believe this will change the food and beverage landscape forever'". foodnavigator-usa.com. William Reed Business Media SAS.

- Gelski, Jeff (30 June 2015). "New low-calorie sweetener to launch at I.F.T." Food Business News. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "AllSweet". Anderson Global Group.

- Commissioner, Office of the. "FDA In Brief - FDA In Brief: FDA allows the low-calorie sweetener allulose to be excluded from total and added sugars counts on Nutrition and Supplement Facts labels when used as an ingredient". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-17.