Politics of Eritrea

Politics of Eritrea takes place in a framework of a single-party presidential republican totalitarian dictatorship. The President officially serves as both head of state and head of government. The People's Front for Democracy and Justice is the only political party legally permitted to exist in Eritrea. The popularly elected National Assembly of 150 seats, formed in 1993 shortly after independence from Ethiopia, elected the current president, Isaias Afewerki. There have been no general elections since its official independence in 1993. The country is governed under the constitution of 1993. A new constitution was ratified in 1997, but has not been implemented. Since the National Assembly last met in 2002, President Isaias Afwerki has exercised the powers of both the executive and legislative branches of government.

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Eritrea |

| Constitution (not enforced) |

| Elections |

|

|

Following a successful referendum on independence for the Autonomous Region of Eritrea between 23 and 25 April 1993, on 19 May of that year, the Provisional Government of Eritrea (PGE) issued a Proclamation regarding the reorganization of the Government. It declared that during a four-year transition period, and sooner if possible, it would draft and ratify a constitution, prepare a law on political parties, prepare a press law, and carry out elections for a constitutional government. In March 1994, the PGE created a constitutional commission charged with drafting a constitution flexible enough to meet the current needs of a population suffering from 30 years of civil war as well as those of the future, when stability and prosperity change the political landscape.

Commission members have traveled throughout the country and to Eritrean communities abroad holding meetings to explain constitutional options to the people and to solicit their input. A new constitution was promulgated in 1997 but has not yet been implemented, and general elections have been postponed. A National Assembly, composed entirely of the PFDJ and its allies, was established as a transitional legislature; elections have been postponed indefinitely since a border war with Ethiopia.

Independent local sources of political information on Eritrean domestic politics are scarce; in September 2001 the government closed down all of the nation's privately owned print media, and outspoken critics of the government have been arrested and held without trial, according to domestic and international observers, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. In 2004 the U.S. State Department declared Eritrea a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) for its alleged record of religious persecution.

At independence, the government faced formidable challenges. Beginning with a nascent judicial system, and an education system in shambles, it has attempted to build the institutions of government from scratch, with varying success. Since then, the impact of the border war with Ethiopia, and continued army mobilisation, has contributed to the lack of a skilled workforce. The present government includes legislative, executive, and judicial bodies.

Executive branch

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Isaias Afewerki | PFDJ | 24 May 1991 |

The President nominates individuals to head the various ministries, authorities, commissions, and offices, and the National Assembly ratifies those nominations. The cabinet is the country's executive branch. It is composed of 18 ministries and chaired by the president. It implements policies, regulations, and laws and is, in theory, accountable to the National Assembly.

The Ministries are:

|

|

|

Legislative branch

| Members | Seats |

|---|---|

| Appointed members | 64 |

| Central Committee of the People's Front for Democracy and Justice | 40 |

| Total | 104 |

The legislature, the National Assembly appointed in 1993, includes 75 members of the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) and 75 additional 'popularly elected' members. Those elected by the general population must include 11 women and representation of 15 Eritreans not currently living in the state.[1] The National Assembly is the highest legal power in the government until the establishment of a democratic, constitutional government. Within the Eritrean Constitution, the legislature would remain the strongest arm of the government. The legislature sets the internal and external policies of the government, regulates the implementation of those policies, approves the budget, and elects the president of the country. Its membership has not been renewed through national elections, and its latest session was in 2002.[2]

Lower Regional Assemblies are also in each of Eritrea's six zones. These Assemblies are responsible for setting a local agenda in the case that they are not overruled by the National Assembly. These Regional Assemblies are popularly elected within each region. Unlike the National Assembly, however, the Regional administrator is not selected by the Regional Assembly.

Political parties and elections

Eritrea is a single-party state run by the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ). No other political groups are legally allowed to organize. The PFDJ's most recent party congress was held in 2002, and its members have not met since.[2]

Legislative elections were set for 1997 and then postponed until 2001, it was then decided that because 20% of Eritrea's land was under occupation that elections would be postponed until the resolution of the conflict with Ethiopia. Local elections have continued in Eritrea. The most recent round of local government elections was held in May 2003. On further elections, the President's Chief of Staff, Yemane Ghebremeskel said,[3]

The electoral commission is handling these elections this time round so that may be the new element in this process. The national assembly has also mandated the electoral commission to set the date for national elections, so whenever the electoral commission sets the date there will be national elections. It’s not dependent on regional elections, although that might be a very helpful process. Multipartyism, in general principle yes, it is there but the law on political parties has to be approved by the national assembly. It was not approved the last time. The view from the beginning was that you don’t necessarily need a party law to hold national elections. You can have national elections and the party law can be adopted at any time. So in terms of commitment it’s very clear, in terms of the process it has its own pace, its own characteristics.

Eritrean opposition groups in exile

- Eritrean Islamic Jihad (EIJ) ?

- Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), Abdullah Muhammed

- Eritrean Liberation Front-Revolutionary Council (ELF-RC), Ahmed Nasser (died 26 March 2014)[4]

- Eritrean Liberation Front-United Organization (ELF-UO), Mohammed Said Nawd

- ምንቅስቓስ ንብሩህ መጻኢ ኤርትራ (Eritrean bright future movement) Beyene Ghebrezgabihier

- Eritrean People's Democratic Front (EPDF), Tewelde Ghebreselassie

- Eritrean Solidarity Movement for National Salvation (ESMNS) Grassroots Movement led by Tesfu Atsbeha ESMNS official website

- Democratic Movement for Liberation of Eritrean Kunama (DMLEK) ( Kernelewos)

- The Agazyan National Front mehari yowhans

Regional issues

Eritrea has had rough relations with most of its neighbors in the 1990s and initiated both small-scale and large-scale battles against Sudan, Djibouti, Yemen and Ethiopia. Eritrea invaded the Hanish islands of Yemen, Sudan blamed Eritrea for attacks in Eastern Sudan, UN commission accused Eritrea for invading Ethiopia and Djibouti officials accused Eritrea for shelling towns in Djibouti in 1996.[5][6][7][8] After this, Eritrea has made efforts to solve relations with Sudan and Djibouti, though relations with Yemen and Ethiopia remain sour. In 2008, an attack on Djibouti led by the Eritrean Army on the tip South end of the country led to several civilians being killed, and further international tensions. Eritrea abandoned the regional bloc IGAD which is membered by the four nations and Kenya. Due to the nature of its environment, many Eritreans risk their lives to flee the country and reach the Mediterranean and Europe.[9]

Judicial branch

The judiciary operates independently of both the legislative and executive bodies, with a court system that extends from the village through to the regional and national levels. Such isolation, in fact, can be seen in the judiciary’s exclusion from Proclamation no. 86/1996 for the Establishment of Regional Administration (PERA). PERA outlines the responsibilities and discretions of the legislative and executive branches but notably excludes the judiciary branch.[10] In addition to its separation, the constitution also upholds the courts to protect the meselat (rights), rebhatat (rights), and natznetat (freedoms) of government, organizations, associations, and individuals.[11] With regard to the legal profession, according to a 2015 source,[12] there is not a bar association in Eritrea. The Legal Committee of the Ministry of Justice oversees the admission and requirements to practice law. Although the source goes on to state that there have been female judges, there is no indication as to how demographic groups, such as women, have fared in the legal field.

Court Structure

The Eritrean judicial system is split into three different courts: the Civil Court, the Military Court, and the Special Court.[11] Indeed, each level possesses distinct characteristics and responsibilities to uphold the rule of law in Eritrea.

Civil Court

At the lowest level of the Eritrean judiciary, the Civil Court eases the pressures of the higher courts by ruling on minor infractions of the law with sums less than 110,000 nakfa, or 7,299 US dollars.[11] Notably, there are multiple divisions within the Civil Court; the structure has three tiers, the local "community courts," the regional courts and the national High Court.

The community courts work on the basis of the area, the local rules and customs. At the bottom tier, they operate on a single-judge bench system where only one judge presides over each case. Here, village judges are elected, though typically they are the village elders and do not possess formal training.[11] Although these judges mainly preside over civil cases, those who are well-versed in criminal law may rule on these kinds of cases, as well.[11] Within Eritrea, There are a total of 683 community courts across the country with the number of magistrates totalling to 2,049, i.e. 55 in the Central Region, 213 in the South, 178 in Gash-Barka, 109 in Anseba, 98 in the Northern and 30 in the Southern Red Sea regions."[13] If a dispute cannot be resolved in the community courts it can be appealed to the next level of judicial administration, the regional courts, natively known as Zoba Courts, which operate on a three-judge bench system.[11] The Zoba Courts adjudicate civil, criminal, and Shari’a law, the last of which handles cases regarding members of the Islam faith.[11] Decisions in the Zoba Courts can be appealed to the High Courts, which is primarily appellate in nature but also operates as a first-instance court for murder, rape, and serious felonies. This three-judge bench system holds jurisdiction in civil, criminal, commercial, and Shari’a law.[11] Final appeals from the High Court are taken to the Supreme Court with a panel of five judges. The president of this Supreme Court is the president of the High Court, as well, and is accompanied by four other judges from the High Court to interpret the law.[11]

Military Court

The Military Court composes another component of the Eritrean judicial system. The Military Court’s jurisdiction falls under cases brought against members of the armed forces as well as crimes committed by and against the members of the armed forces.[11] In addition, this court may also sentence military personnel that express criticism of the government. As one may expect, all presiding judges are veterans of the military. There are two levels to the Military Branch, but neither are appellate courts; in fact, the Eritrean High Court (from the Civil Court) fulfils this task.[11] Given the large presence and popularity of militarization in Eritrea, the Military Court embodies an “enormous - and unchecked - judicial importance in the country”.[11]

Special Court

The Special Court, the third and final element to the Eritrean judicial system, operates on a three-judge bench system and works under three themes: general criminal cases, corruption, and illegal foreign exchange and smuggling.[11] Judges in this branch are either senior military members or former members of the Eritrean People's Liberation Front, the leading group that fought for Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia.[11] The Special Court is defined by its high level of autonomy and discretion; in fact, the Special Court operates in complete secrecy, so no published records of its procedures available.[11] Although the Office of the Attorney-General decides which cases are heard, judges are not bound by the Code of Criminal Procedure, Penal Code, or any precedence in law; rather, judges rely on their “conscience” to make most decisions.[11] Furthermore, the court can re-open and adjudicate cases that have already been processed through federal courts, allowing for the occurrence of double jeopardy. Judges can also, without limit, intensify punishments that the government sees as insufficient.[11] Moreover, during a trial, defendants are denied any form of representation and may even be asked to defend themselves in person.[11] Except for rare instances when appeals are made to the Office of the President, there are no ways to challenge the rulings that result from the Special Court.[11]

Discrepancies Within the Judicial System

By Constitutional measures, the law prohibits “indefinite and arbitrary” detention, requires arrested persons be brought before a court within 48 hours, and sets a limit of 28 days in which an arrested person may be held without being charged for a criminal offense.[11] However, this statute is often not practiced, especially in regard to political crimes. The Constitution also grants defendants the right to be present during the trial with legal representation for punishments exceeding ten years; yet, many lack the resources to retain a lawyer and the Eritrean judicial system lacks qualified lawyers who can serve as defense attorneys.[11] Although the High Court does uphold the right to confront and question witnesses, present evidence, gain access to government-held evidence, and appeal against a decision, the Special Court disregards the above qualities.[11] In addition, Eritrea’s absence of civil judicial procedures addressing human rights violations by the government contradicts Article 24 of the constitution that allows for this redress for citizens.[11] The last contradiction is of the judges, themselves. Of course, the judges are physically able, for Proclamation on the Establishment of Community Courts No. 132/2003 bars citizens with mental disabilities from standing for elections as judges;[14] however, judges do not receive training or do not have prior experience in law. Many are military men who form their decision based on conscience and the political values of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF).[11] Lastly, despite constitutional calls for an independent judiciary, the president of Eritrea continues to intervene in the judicial decision-making.[11]

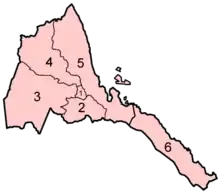

Administrative divisions

Eritrea is divided into 6 regions (or zobas) and subdivided into approximately 55 districts or sub-zobas. The regions are based on the hydrological properties of area. This has the dual effect of providing each administration with ample control over its agricultural capacity and eliminating historical intra-regional conflicts.

The regions are included followed by the Sub-region:

| Region (ዞባ) (location on map) | Sub-region (ንዑስ ዞባ) |

| Central (Maekel Zoba) (Al-Wasat) (1) | Berikh, Ghala Nefhi, North Eastern, Serejaka, South Eastern, South Western |

|---|---|

| Southern (Debub Zoba) (Al-Janobi) (2) | Adi Keyh, Adi Quala, Areza, Debarwa, Dekemhare, Kudo Be'ur, Mai-Mne, Mendefera, Segeneiti, Senafe, Tserona |

| Gash-Barka (3) | Agordat City, Barentu City, Dghe, Forto, Gogne, Haykota, Logo Anseba (Awraja Adi Naamen), Mensura, Mogolo, Molki, Omhajer (Guluj), Shambuko, Tesseney, Upper Gash |

| Anseba (4) | Adi Teklezan, Asmat, Elabered, Geleb, Hagaz, Halhal, Habero, Keren City, Kerkebet, Sela |

| Northern Red Sea (Semienawi-QeyH-Bahri Zoba) (Shamal Al-Bahar Al-Ahmar) (5) | Afabet, Dahlak, Ghelalo, Foro, Ghinda, Karura, Massawa, Nakfa, She'eb |

| Southern Red Sea (Debubawi-QeyH-Bahri Zoba) (Janob Al-Bahar Al-Ahmar) (6) | Are'eta, Central Dankalia, Southern Dankalia |

Foreign relations

External issues include an undemarcated border with the Sudan, a brief war with Yemen over the Hanish Islands in 1996, and a recent border conflict with Ethiopia.

The undemarcated border with Sudan poses a problem for Eritrean external relations.[15] After a high-level delegation to the Sudan from the Eritrean Ministry of Foreign Affairs ties are being normalized. While normalization of ties continues, Eritrea has been recognized as a broker for peace between the separate factions of the Sudanese civil war, with Hassan al-Turabi crediting Eritrea in playing a role in the peace agreement between the Southern Sudanese and the government.[16] Additionally, the Sudanese Government and Eastern Front rebels requested that Eritrea mediate their peace talks in 2006.[17]

A dispute with Yemen over the Hanish Islands in 1996 resulted in a brief war. As part of an agreement to cease hostilities the two nations agreed to refer the issue to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague. At the conclusion of the proceedings, both nations acquiesced to the decision. Since 1996 both governments have remained wary of one another but relations are relatively normal.[18]

The undemarcated border with Ethiopia is the primary external issue facing Eritrea. This led to a long and bloody border war between 1998 and 2000. As a result, the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) is occupying a 25 km by 900 km area on the border to help stabilize the region.[19] Disagreements following the war have resulted in stalemate punctuated by periods of elevated tension and renewed threats of war.[20][21][22] Central to the continuation of the stalemate is Ethiopia's failure to abide by the border delimitation ruling and reneging on its commitment to demarcation. The stalemate has led the President of Eritrea to write his Eleven Letters to the United Nations Security Council, which urges the UN to take action on Ethiopia. Relations between the two countries is further strained by the continued effort of the Eritrean and Ethiopian leaders in supporting each other's opposition.

The 8–9 July 2018 took place the 2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia summit (also 2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia peace summit) in Asmara, Eritrea, between Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and officials from the two countries.

The two leaders signed a joint declaration on 9 July, formally ending the border conflict between both countries, restoring full diplomatic relations, and agreeing to open their borders to each other for persons, goods and services. The joint statement was also considered to close all chapters regarding the Eritrean–Ethiopian War (1998–2000) and of the following Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict (2000–2018) with sporadic clashes.

References

- "Eritrea - Political structure". www.eritrea.be. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44848184

- "Interview of Mr. Yemane Gebremeskel, Director of the Office of the President of Eritrea". PFDJ. 2004-04-01. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Prominent Eritrean opposition leader dies". www.worldbulletin.net/.

- Eritrea invades Yemen's hanish islands Archived 2008-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- "BBC News - Africa - Sudan accuses Eritrea of attack". news.bbc.co.uk.

- "DJIBOUTI: IRIN Focus on mounting tension with Eritrea [19991112]". www.africa.upenn.edu.

- UN accuses Eritrea for Invading Ethiopia Archived 2013-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "Eritrea profile". 2018-11-15. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- Bereketeab, Redie (2012). "Re-examining Local Governance in Eritrea: The Redrawing of Administration Regions". African and Asian Studies. 11: 12.

- Tronvoll, Kjetil. (2014). The African Garrison State: Human Rights and Political Development in Eritrea. Rochester, New York: Boydell and Brewer Inc. pp. 47–55. ISBN 978-1-84701-069-8.

- "UPDATE: Introduction to Eritrean Legal System and Research - GlobaLex". nyulawglobal.org. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- "Community Courts: Helping Citizens Settle Disputes out of Courts". PFDJ. 2005-11-23. Archived from the original on 2006-09-29. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- Futsum, Abbay (2015). "Eritrea". African Disability Rights Yearbook. 3: 172–175.

- "Eritrea-Sudan relations plummet". BBC. 2004-01-15. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Turabi terms USA "world's ignoramuses", fears Sudan's partition". Sudan Tribune. 2005-11-04. Archived from the original on 2006-07-18. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Sudan demands Eritrean mediation with eastern Sudan rebels". Sudan Tribune. 2006-04-18. Archived from the original on 2006-05-19. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Flights back on between Yemen and Eritrea". BBC. 1998-12-13. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Q&A: Horn's bitter border war". BBC. 2005-12-07. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Horn tensions trigger UN warning". BBC. 2004-02-04. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Army build-up near Horn frontier". BBC. 2005-11-02. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- "Horn border tense before deadline". BBC. 2005-12-23. Retrieved 2006-06-07.