Pistosaurus

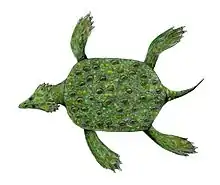

Pistosaurus ( "saurus" in Greek meaning "reptile" and "lizard") is an extinct genus of aquatic sauropterygian reptile closely related to plesiosaurs. Fossils have been found in France and Germany, and date to the Middle Triassic. It contains a single species, Pistosaurus longaevus. Pistosaurus is known as the oldest "subaquatic flying" reptile on earth.

| Pistosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Family: | †Pistosauridae Zittel, 1887 |

| Genus: | †Pistosaurus Meyer, 1839 |

| Type species | |

| †Pistosaurus longaevus Meyer, 1839 | |

The skull of Pistosaurus is generally resembles that of other Triassic sauropterygians. However, there are several synapomorphies that make Pistosaurus distinguished: the long, slender, snout; the possession of splint-like nasals that are excluded from the external naris; and the posterior extension of the premaxilla to the frontals.[1] Based on synapomorphies such as the small nasals size and the presence of interpterygoid vacuity, Pistosaurus is more closely related to Plesiosauria than to Nothosaurus.[1]

Pistosaurus is often mistaken with Nothosaurus and Plesiosauria. Nothosaurus belongs to the clade Nothosauroidea from the middle Triassic (approximately 199-251 million years ago); while Pistosaurus belongs to stem group Plesiosauria; and both Pistosaurus and Plesiosauria belongs to clade Pistosauroidea from Triassic. Both Nothosauroidea and Pistosauroidea belong to Sauropterygia.[1]

Description and paleobiology

Pistosaurus was about 3 metres (10 ft) long, and had a body form resembling that of nothosaurs, aquatic reptiles that flourished during the Triassic. However, the vertebral column was stiff, like that of a plesiosaur, implying that the animal used its paddle-like flippers to propel itself through the water, as the plesiosaurs probably did. The head also resembled that of a plesiosaur, but with the primitive palate of a nothosaur, and numerous, sharp teeth ideal for catching and eating fish.[2]

Post-cranial skeleton

The description below is based on the specimen examined by paleontologist Sues in 1987.

Pectoral girdle and forelimbs

The structure of pectoral girdle and humerus are used to support the anterior part of the body.[3] The scapula in pectoral girdle of Pistosaurus consists with a massive body and a short posterodorsal process. It is smaller in size compared to coracoid. And its lateral margin of the body is gently convex anteroposteriorly while the medial margin is more strongly convex.[3]

The coracoid bone of Pistosaurus is flat and expanded medially.[3] The glenoid region is similar to Nothosaurus in development: both the slight notching of its margin and a distinct facet contact with the humeral head. There is also a ridge like thickening which links the glenoid to posteromedial region of the coracoid.[3] This feature is a synapomorphy that appears in plesiosaurs, which is a thickened ridge passes transversely across the anterior portion of the coracoid to connect the glenoid region. This feature is suggested related to compressional force by limb motion in Pistosaurus.[3]

A specimen of the left humerus of Pistosaurus analyzed by Paleontologist A.R.I. Cruickshank is one of the largest specimens recorded: 245mm long and 45mm wide at the mid-shaft.[4] The specimen showing that the axis of Pistosaurus' humerus is straight, with the distal end slightly expanded posteriorly.[4] From proximal view, the head of the humerus is concave, which is a sign of a substantial cap of cartilage at the head of humerus. The humerus of Pistosaurus also lacks entepicondylar foramen.[4]

Pistosaurus has a strongly flattened ulna. It has medium length and nearly symmetrical in dorsal view.[3] Its anterior margin is more curved and thicker than the posterior one. This feature broads the wide spatium interosseum enclosed between radius and ulna.[3] The proximal end of radius is less expanded than that of ulna, while the distal end is less expanded than proximal one but thickened.[3] The anterior margin is nearly straight while the posterior margin is more curved compared to the anterior one. Like other sauropterygians, the radius of Pistosaurus is slightly longer than the ulna.[3]

Pelvic girdle

The pelvic girdle of Pistosaurus is more similar to primitive sauropterygians than to plesiosaurs.

The ilium of Pistosaurus has an iliac blade, which has almost parallel anterior and posterior margins.[3] Same as other non-plesiosaur sauropterygians, the ilium in Pistosaurus contacts both the pubis and the ischium, forming a ring-like structure. The ilium from Pistosaurus is relatively large in size compared to Nothosaurus, whose ilia did not appear to have any elongated blade.[3]

The femur of Pistosaurus is longer than its humerus. Its anterior margin is almost straight whereas the posterior margin is concave.[3] According to the specimen provided by paleontologist Sues, the proximal articular end is much more robust than the distal one, and is more or less triangular in transverse section.[3]

Classification

Although it is unlikely that Pistosaurus was a direct ancestor of the plesiosaurs, the mixture of features suggests that it was closely related to that group.[2]

The following cladogram follows an analysis by Ketchum & Benson, 2011.[5]

The classification for Plesiosauria was difficult at the first place. The anatomy of stem group Sauropterygia has very primitive synapomorphies such as dermal palate. Initially, Plesiosauria were suggested related to Pistosauroidea, which belongs to Eusauropterygia from Triassic. Three genera of Plesiosauria was known in the history: Corosaurus alvocensis, Cymatosaurus, and Pistosaurus longaevus.[6] A later discovery of a new Pistosauridea from middle triassic of Nevada by paleontologist Sander indicates that Augustasaurus is closely related to Pistosaurus, while there are several difference including axial skeleton.[7]

References

- Krahl, Anna, et al. "Evolutionary Implications of the Divergent Long Bone Histologies of Nothosaurus and Pistosaurus (Sauropterygia, Triassic)." BMC Evolutionary Biology, vol. 13, 2013, p. 123.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 73. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Sues, H.-D. "Postcranial Skeleton of Pistosaurus and Interrelationships of the Sauropterygia (Diapsida." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 90, no. 2, 1987, pp. 109–131.

- Cruickshank, A. "A Pistosaurus-like Sauropterygian from the Rhaeto-Hettangian of England." Mercian Geologist, vol. 14, no. 1, 1996, pp. 12–13.

- Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01083.x.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Rieppel, Olivier, et al. "The Skull of the Pistosaur Augustasaurus from the Middle Triassic of Northwestern Nevada." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 22, no. 3, 2002, pp. 577–592.

- Sander, P. Martin, et al. "A New Pistosaurid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Nevada and Its Implications for the Origin of the Plesiosaurs." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 17, no. 3, 1997, pp. 526–533.

- Diedrich, Cajus G., et al. "The Oldest "Subaquatic Flying" Reptile in the World; Pistosaurus Longaevus Meyer, 1839 (Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Europe." Bulletin of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, vol. 61, 2013, pp. 169–215.

- Taylor, Michael A. "Palaeontology; Sea-Saurians for Sceptics." Nature (London), vol. 338, no. 6217, 1989, pp. 625–626.

- Huene, F. V. "Pistosaurus, a Middle Triassic Plesiosaur." American Journal of Science, vol. 246, no. 1, 1948, pp. 46–52.

- Surmik, Dawid, et al. "Two Types of Bone Necrosis in the Middle Triassic Pistosaurus Longaevus Bones: the Results of Integrated Studies." Royal Society Open Science, vol. 4, no. 7, 2017, pp. Royal Society Open Science, 2017, Vol.4(7).

.png.webp)