Morturneria

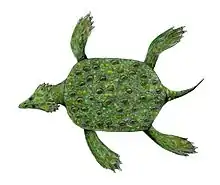

Morturneria is an extinct genus of plesiosaur from the Late Cretaceous of what is now Antarctica.

| Morturneria Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Elasmosauridae |

| Genus: | †Morturneria Chatterjee and Creisler, 1994 |

| Species | |

| |

History of research

The Lopez de Bertodano Formation is located on Seymour Island, Antarctica, with exposures present in all but the northernmost third of the island. During the summers of 1981-1982, 1983-1984, and 1984-1985, paleontological expeditions recovered eight partial plesiosaur skeletons in the formation. One of these, TTU P9219, consisted of a skull and some cervical vertebrae. It was found in the upper part of the formation, informally known as the 'molluscan units', high up in a ravine. It was preserved within a tough, calcareous nodule, from which it was difficult to remove. While excavating the specimens, the dig teams faced difficulty in removing the strata above the fossils, due to the presence of permafrost. The cold temperatures also prevented the plaster from setting, so the teams used camp stoves and aluminium foil to heat it up, allowing it to harden. The specimen was prepared with the usage of power tools and acetic acid to remove the surrounding rock.[1]

In 1989, Sankar Chatterjee and Bryan Small named the new genus and species Turneria seymourensis to contain TTU P9219. The specific name refers to Seymour Island, while the generic name honored Dr. Mort Turner, who was interested in the paleontological studies taking place there.[1] However, the name Turneria was preoccupied, already in use for a genus of hymenopteran insect. In light of this, Chatterjee and Benjamin Creisler published a new name for the plesiosaur, Morturneria, in 1994. As before, the generic name honors Mort Turner.[2]

However, a 2003 study by Zulma Gasparini and colleagues found Morturneria to be so similar to Aristonectes, they found it most likely that it was merely a juvenile A. parvidens. Since Aristonectes was named first, they concluded that Morturneria was a junior synonym of this genus.[3] In 2017, a study led by F. Robin O'Keefe reanalyzed the skull of Morturneria. While they agreed with Gasparini and colleagues that the specimen was a juvenile, they found it to be distinct from Aristonectes and a valid genus once more. They also found that the Texas Tech University collections from Seymour Island contain postcranial material from adult plesiosaurs that, while similar to Aristonectes, definitely belonged to a different taxon, further supporting the separation of the two genera.[4] In a 2019 thesis, Elizabeth Lester assigned another specimen found by the expeditions that recovered the holotype of Morturneria seymourensis to the species. This specimen, TTU P9217, consists of more cervical vertebrae, a right humerus, a nearly complete left forelimb missing the proximal end of the humerus, and a left femur. Additionally, more material pertaining to the holotype was reported; a possible humeral head, an epipodial (lower limb bone), a possible carpal, and three phalanges.[5]

Description

The external naris (nostril opening) is formed by the premaxilla on the inner and most of the front edge, the maxilla on the rest of the front and the outer edge, and the frontal and prefrontal on the rear edge. The upper surfaces of the premaxillae and maxillae bore many foramina (pits). The premaxillae each bore at least eight teeth. After the frontmost five alveoli (tooth sockets) in the upper jaw, the borders of the alveoli become poorly defined or absent, with the upper tooth row appearing to be a groove on the maxilla. Instead of being directed downwards, the teeth were pointed outwards, where they interlocked. The upper edge of the orbit (eye opening) is composed of the frontal, with the prefrontal participating in the region intermediate between the upper and front edges. There is a prominent bend in the frontal, with the front region flaring outwards. This may have protected the eye. The outer margin of the orbit is bowed inwards, thanks to an enlargement on the maxilla.[4]

Paleobiology

In 2003, Gasparini interpreted the M. seymourensis holotype as a juvenile because of its smaller size and the lack of fusion of the neural arches to the vertebrae.[3] The downward-curving teeth of the lower jaw indicate that unlike most plesiosaurs, Morturneria was capable of filter-feeding, scooping sand from sediments, ejecting sediment-laden water, and preying on amphipods and other tiny prey organisms.[4]

References

- Chatterjee, S.; Small, B. J. (1989). "New plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica" (PDF). Geological Society Special Publications. 47 (1): 197–215.

- Chatterjee, S; Creisler, B. S. (1994). "Alwalkeria (Theropoda) and Morturneria (Plesiosauria), new names for preoccupied Walkeria Chatterjee, 1987 and Turneria Chatterjee and Small, 1989". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (1): 142–142. doi:10.1080/02724634.1994.10011546.

- Gasparini, Z.; Bardet, N.; Martin, J. E.; Fernandez, M. (2003). "The elasmosaurid plesiosaur Aristonectes Cabrera from the latest Cretaceous of South America and Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (1): 104–115.

- O'Keefe, F. R.; Otero, R. A.; Soto-Acuña, S.; O'Gorman, J. P.; Godfrey, S. J.; Chatterjee, S. (2017). "Cranial anatomy of Morturneria seymourensis from Antarctica, and the evolution of filter feeding in plesiosaurs of the Austral Late Cretaceous". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (4): e1347570.

- Lester, Elizabeth (2019). Description and histology of a small-bodied elasmosaur and discription of Mortuneria seyemourensis postcranium (Thesis). Marshal University.

.png.webp)