Malabar District

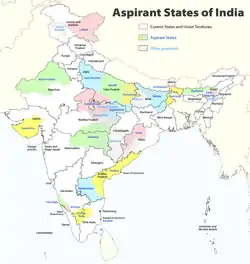

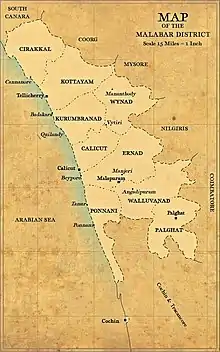

Malabar District was an administrative district of Madras Presidency[2] in British India and independent India's Madras State. It was the most populous and the third-largest district in the erstwhile Madras State.[3] The British district included the present-day districts of Kannur, Kozhikode, Wayanad, Malappuram, Palakkad (excluding some areas of Alathur and Chittur Taluks), Chavakad Taluk and parts of Kodungallur Taluk of Thrissur district (former part of Ponnani Taluk), and Fort Kochi area of Ernakulam district in the northern and central parts of present Kerala state, the Lakshadweep Islands, and the Gudalur taluk and Pandalur taluk of Nilgiris district in Tamil Nadu. After the formation of Kerala state in 1956, present Kasaragod district also became a part of Malabar.

| Malabar District | |

|---|---|

| District of British India | |

| 1792–1957 | |

Flag

.jpg.webp) Coat of arms

| |

Malabar District, Revenue Divisions and Taluks | |

| Capital | Kozhikode |

| Area | |

• 1951 | 15,027[1] km2 (5,802 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1951 | 4,758,842[1] |

| History | |

• Territories ceded by Tipu Sultan | 1792 |

| 1957 | |

The district lay between the Arabian Sea on the west, South Canara District on the north, the Western Ghats to the east, and the princely state of Cochin to the south. The district covered an area of 15,027 square kilometres (5,802 sq mi), and extended 233 km (145 mi) along the coast and 40–120 kilometers (25–75 miles) inland. The name Mala-bar means the "hillside slopes". Kozhikode was the capital of Malabar. It was divided into North Malabar and South Malabar in 1793 for administrative convenience.

Etymology

Until the arrival of British, the term Malabar was used as a general name for Kerala. From the time of Cosmas Indicopleustes (6th century CE) itself, the Arab sailors used to call Kerala as Male. Al-Biruni (AD 973 - 1048) must have been the first writer to call this country Malabar. The Arab writers had called this place Malibar, Manibar, Mulibar, and Munibar. Malabar is reminiscent of the word Malanad which means the land of hills. According to William Logan, the word Malabar comes from a combination of the Malayalam word Mala (hill) and the Persian/Arabic word Barr, (country/continent). [4] Mala in Malayalam means "hill". Varam means "slope" or "side of a hill". In Northern and North-Central Kerala (including all Malabar districts except Palakkad, Thrissur and parts of Malappuram district)/Kannada, where Malabar proper is located, words that start in Southern Malayalam/Tamil with the letter "V" tend to be pronounced with the letter "B". Thus, some of the historians argue that the word Malabar comes from the Northern Malayalam words Mala-Bar(am) meaning "hillside land".

History

Under Zamorin of Calicut

At the peak of their reign, the Zamorins of Kozhikode ruled over a region from Kollam (Quilon) in the south to Panthalayini Kollam (Koyilandy) in the north.[5][6] Ibn Battuta (1342–1347), who visited the city of Kozhikode six times, gives the earliest glimpses of life in the city. He describes Kozhikode as "one of the great ports of the district of Malabar" where "merchants of all parts of the world are found". The king of this place, he says, "shaves his chin just as the Haidari Fakeers of Rome do... The greater part of the Muslim merchants of this place are so wealthy that one of them can purchase the whole freightage of such vessels put here and fit-out others like them".[7] Ma Huan (1403 AD), the Chinese sailor part of the Imperial Chinese fleet under Cheng Ho (Zheng He)[8] states the city as a great emporium of trade frequented by merchants from around the world. He makes note of the 20 or 30 mosques built to cater to the religious needs of the Muslims, the unique system of calculation by the merchants using their fingers and toes (followed to this day), and the matrilineal system of succession. Abdur Razzak (1442–43), Niccolò de' Conti (1445), Afanasy Nikitin (1468–74), Ludovico di Varthema (1503–1508), and Duarte Barbosa witnessed the city as one of the major trading centres in the Indian subcontinent where traders from different parts of the world could be seen.[9][10]

Under Arakkal kingdom

St. Angelo Fort was built in 1505 by Dom Francisco de Almeida, the first Portuguese Viceroy of India. The Dutch captured the fort from the Portuguese in 1663. They modernized the fort and built the bastions Hollandia, Zeelandia, and Frieslandia that are the major features of the present structure. The original Portuguese fort was pulled down later. A painting of this fort and the fishing ferry behind it can be seen in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. The Dutch sold the fort to the king Ali Raja of Arakkal in 1772. The British conquered it in 1790 and used it as one of their major military stations on the Malabar Coast. During the 17th century, Kannur was the capital city of the only Muslim Sultanate in the Malabar region - Arakkal.[11]

Kannur served as the British military headquarters on India's west coast until 1887. In conjunction with her sister city, Thalassery, it was the third-largest city on the western coast of British India in the 18th century after Bombay and Karachi.

Portuguese occupation

The maritime spice trade monopoly in the Indian Ocean stayed with the Arabs during the High and Late Middle Ages. However, the dominance of Middle East traders was challenged in the European Age of Discovery. After Vasco Da Gama's arrival in Kappad Kozhikode in 1498, the Portuguese began to dominate eastern shipping, and the spice-trade in particular.[12][13][14] The Zamorin of Kozhikode permitted the new visitors to trade with his subjects such that Portuguese trade in Kozhikode prospered with the establishment of a factory and a fort. However, Portuguese attacks on Arab properties in his jurisdiction provoked the Zamorin and led to conflicts between them.

The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between the Zamorin and the King of Kochi allied with Kochi. When Francisco de Almeida was appointed as Viceroy of Portuguese India in 1505, his headquarters was established at Fort Kochi (Fort Emmanuel) rather than in Kozhikode. During his reign, the Portuguese managed to dominate relations with Kochi and established a few fortresses on the Malabar Coast.[15] Fort St Angelo or St. Angelo Fort was built at Kannur in 1505 and Fort St Thomas was built at Kollam(Quilon) in 1518 by the Portuguese.[16] However, the Portuguese suffered setbacks from attacks by Zamorin forces in Malabar region; especially from naval attacks under the leadership of Kozhikode admirals known as Kunjali Marakkars, which compelled them to seek a treaty. An insurrection at the Port of Quilon between the Arabs and the Portuguese led to the end of the Portuguese era in Quilon. In 1571, the Portuguese were defeated by the Zamorin forces in the battle at Chaliyam Fort.[17] The Portuguese were ousted by the Dutch East India Company, who during the conflicts between the Kozhikode and the Kochi, gained control of the trade.[18]

Under Mysore Sultans

In 1757, to check the invasion of the Zamorin of Calicut, the Palakkad Raja sought the help of Hyder Ali of Mysore. In 1766, Haider Ali of Mysore defeated the Samoothiri of Kozhikode – an East India Company ally at the time – and absorbed Kozhikode to his state.[6][19] After the Third Mysore War (1790–1792), Malabar was placed under the control of the Company. Eventually, the status of the Samoothiri was reduced to that of a pensioner of the Company (1806).[6][20] When Wayanad was under Hyder Ali's rule, the ghat road from Vythiri to Thamarassery was constructed.[21] Then the British rulers developed this route to Carter road.[22] His son and successor, Tipu Sultan, launched campaigns against the expanding British East India Company, resulting in two of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars.[23][24]

Colonial period

Tipu ultimately ceded the Malabar district and South Kanara to the company in the 1790s; both were annexed to the Bombay Presidency of British India in 1792.[25][26][27] Later the region was transferred into the Madras Presidency. The administrative headquarters were at Calicut (Kozhikode). Local affairs were managed by the District Board at Calicut along with Taluk Boards located at Malappuram, Thalassery, Palakkad and Mananthavady.[28] During 19th century, British established their army stations at Kannur, Malappuram, and Calicut. Malappuram which was one of the European military stations in Madras presidency since 1852, also became the special police force headquarters of Malabar District, with the establishment of the Malabar Special Police in 1885.[29]

According to William Logan, the Taluks of Malabar could be subdivided on the basis of the feudal lords who ruled them before as given below:

Chirakkal Taluk

The Amsoms included in Chirakkal Taluk was classified into two divisions of Kolathunadu and Randathara (also called Poyanadu). There were 44 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30]

1. Kolathunadu

Kolathunadu was the land where Kolattiri Rajas (Chirakkal family) were historically considered as the main authority. It was ruled by Kolattiri Raja, Mannanars,[31] Arakkal Kingdom, and Kingdom of Mysore in various periods.[30] It consisted of the following 36 Amsoms:

- Payyannur

- Vellur

- Karivellur

- Korom

- Eramam

- Kuttur (Payyanur)

- Kuttiyeri

- Chuzhali

- Kanhileri

- Kalliad

- Malapattam

- Koyyam

- Kurumathur

- Taliparamba

- Pattuvam

- Ezhome

- Cheruthazham

- Kunhimangalam

- Madayi

- Matool

- Cherukunnu

- Kannapuram

- Irinave

- Pappinisseri

- Kalliasseri

- Morazha

- Kayaralam

- Kuttiattoor

- Maniyoor

- Munderi

- Cheleri

- Kannadiparamba

- Chirakkal

- Azhikode

- Puzhathi

- Elayavoor[30]

2. Randathara

Randathara was also called Poyanadu due to the belief that it was the place from where the Cheraman Perumal took his final departure on the journey to Mecca. It was originally a part of Kolathunadu, but was treated as a different Nadu.[30] It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

- Edakkad

- Chembilode

- Iriveri

- Makreri

- Anjarakkandy

- Mavilayi

- Muzhappilangad[30]

Kottayam Taluk

The Amsoms included in Kottayam Taluk was classified into four divisions- The English Settlement at Tellicherry and Dharmapattanam Islands, Iruvazhinadu, Kurangott Nayar Nadu, and Kottayam. There were 28 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30]

1. The English Settlement at Tellicherry and Dharmapattanam Islands

It was a part of the ancient Kolathunadu. Later it became a part of the Arakkal kingdom and Kingdom of Mysore. The island of Dharmapattanam was claimed by all of the Kolattu Rajas, Kottayam Rajas, and Arakkal Bibi.[30] The English had settled here and started a factory here. It consisted of the following 4 Amsoms:

- Dharmadam

- Thalassery

- Mailanjanmam

- Thiruvangad[30]

2. Iruvazhinadu

It was also under the Kolathunadu earlier. When the English factory was established at Thalassery, Iruvazhinadu was held by six families of Nambiars - Kunnummal, Chandroth, Kizhakkedath, Kampurath, Narangozhi, and Kariyad Nambiars. Kurangott Nayar's possession also probably formed part of the original territory of Iruvazhinadu.[30] It consisted of the following 6 Amsoms:

3. Kurangott Nayar Nadu

It laid between the English settlement at Thalassery and the French settlement at Mahe.[30] It consisted of the following two Amsoms.

- Olavilam

- Kallayi[30]

4. Kottayam

It was also earlier a part of Kolathunadu. The Kottayam Rajas (also known as Puranattu Rajas in the meaning of foreign Kshatriya caste) received their territory from the Kolattu Rajas. Pazhassi Raja was a Kottayam Raja.[30] It consisted of the following 16 Amsoms.

- Koodali

- Pattannur

- Chavassery

- Veliyambra

- Muzhakkunnu

- Gannavam

- Manathana

- Kannavam

- Sivapuram

- Pazhassi

- Kandamkunnu

- Paduvilayi

- Pinarayi

- Nettur

- Kadirur

- Kottayam[30]

Wynad Taluk

The Amsoms included in Wynad Taluk was classified into three divisions- North Wynad, South Wynad, and Southeast Wynad. There were 16 Amsoms in the Taluk.[32]

Wynad was ruled by various kingdoms including Kutumbiyas,[33] Kadambas, Western Chalukyas,[34] Hoysalas,[35] Vijayanagaras, and the Kingdom of Mysore, in various periods. Wynad was home to many tribes. Wynad has relations with the Kingdom of Kottayam and Kurumbranad. Some parts were ruled by the Kottayam dynasty.[32]

1. North Wynad

It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

- Periya

- Edavaka

- Thondernad

- Porunnanore

- Nalloornad

- Ellurnad

- Kuppathod[32]

2. South Wynad

It consisted of the following 6 Amsoms:

3. Southeast Wynad

It was the regions included in the Gudalur and Pandalur Taluks of present Nilgiris district. Southeast Wynad was a part of Malabar District until 31 March 1877, when it was transferred to the neighbouring Nilgiris district due to the heavy population of Malabar and the small area of Nilgiris.[32] It consisted of the following 3 Amsoms.

- Munnanad

- Nambalakode

- Cherankode[32]

Kurumbranad Taluk

The Amsoms included in Kurumbranad Taluk was classified into five divisions- Kadathanad, Payyormala, Payanad, Kurumbranad, and Thamarassery (Some Amsoms of Kurumbranad and Thamarassery were included in the Kozhikode Taluk). There were 57 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30]

1. Kadathanad

It was also part of the Kolathunadu earlier. It formed a major portion of the Thekkalankur (Southern Regent), or the second headquarters of the Kolattiri Rajas. When the English company settled at Thalassery, Kadathanad was under the ancestors of the Kadathanad Rajas, who was then called Bavnores of Badagara.[30] It consisted of the following 31 Amsoms:

- Azhiyur

- Muttungal

- Eramala

- Karthikappalli

- Purameri

- Edacheri

- Iringannur

- Thuneri

- Vellur

- Parakkadavu

- Chekkiad

- Valayam

- Velliyode

- Kunnummal

- Kavilumpara

- Kuttiadi

- Velom

- Cherapuram

- Kottappally

- Ayancheri

- Katameri

- Kuttipuram

- Kummangod

- Ponmeri

- Arakkilad

- Vatakara

- Memunda

- Palayad

- Puduppanam

- Maniyur

- Thiruvallur[30]

2. Payyormala

It was under the control of the Nairs of Payyormala (Paleri, Avinyat, and Kutali Nairs). They were independent chieftains with some theoretical dependence on both the Kurumbranad and the Zamorin of Calicut.[30] It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

- Palery

- Cheruvannur

- Meppayur

- Perambra

- Karayad

- Iringath[30]

3. Payanadu

It was dependent on the Zamorin of Calicut.[30] It consisted of the following 9 Amsoms:

- Keezhariyur

- Moodadi

- Pallikkara

- Meladi

- Viyyur

- Arikkulam

- Melur

- Chemancheri

- Thiruvangoor[30]

4. Kurumbranad

It was subjected to the Kurumbranad family, which was connected with the Kingdom of Kottayam. [30] It consisted of the following 9 Amsoms in Kurumbranad and Kozhikode Taluks:

- Kottur

- Trikkuttisseri

- Naduvannur

- Kavumthara

- Iyyad

- Panangad

- Nediyanad

- Kizhakkoth

- Madavoor[30]

5. Thamarassery

It was also subjected to the Kottayam Rajas. [30] It consisted of the following 9 Amsoms in Kurumbranad and Kozhikode Taluks:

Kozhikode Taluk

The Amsoms included in Kozhikode Taluk was classified into three divisions- Polanad, Beypore (Northern Parappanad), and Puzhavayi. There were 41 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30] (As stated earlier, a part of Kurumbranad and Thamarasseri historical divisions of Kurumbranad Taluk was also included in the Kozhikode Taluk.)

1. Polanad

Polanad was ruled by the Porlathiri Rajas before the conquest of Kozhikode by the Zamorin of Calicut. After the conquest, the Zamorins shifted their headquarters from Nediyiruppu in Eranad to Kozhikode. It became the capital of the Zamorins.[30] It consisted of the following 22 Amsoms:

- Elathur

- Thalakkulathur

- Makkada

- Chathamangalam

- Kunnamangalam

- Thamarassery

- Kuruvattur

- Padinyattumuri

- Karannur

- Edakkad

- Kacheri

- Nagaram

- Kasaba

- Valayanad

- Kottooli

- Chevayur

- Mayanad

- Kovoor

- Perumanna

- Peruvayal

- Iringallur

- Olavanna[30]

2. Beypore (Northern Parappanad)

Parappanad kingdom was a dependent of the Zamorin of Calicut headquartered at Parappanangadi. It was divided into Northern Parappanad and Southern Parappanad. Northern Parappanad was headquartered at Beypore.[30] It consisted of the following 3 Amsoms:

3. Puzhavayi

It was ruled by its own Nairs who had a dependence on both of the Zamorin of Calicut and the Kurumbranad.[30] It consisted of the following 9 Amsoms:

- Kedavur

- Thiruvambady

- Puthur

- Neeleswaram

- Koduvally

- Kanniparamba

- Chuloor

- Manashery

- Pannikode[30]

Ernad Taluk

The Amsoms included in Ernad Taluk was classified into four divisions- Parappur (Southern Parappanad), Ramanad, Cheranad, and Eranad. There were 52 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30] (A part of Cheranad division was under Ponnani Taluk).

1. Parappur (Southern Parappanad)

Southern Parappanad was a dependent of the Zamorin of Calicut. Parappanangadi, the headquarters of Parappanad royal family, was at Southern Parappanad.[30] It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

2. Ramanad

Ramanad was directly ruled by the Zamorin of Calicut.[30] It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

3. Cheranad

Cheranad was also directly ruled by the Zamorin of Calicut.[30] Cheranad was scattered in Eranad and Ponnani Taluks. It consisted of the following 17 Amsoms:

- Vadakkumpuram

- Valiyakunnu

- Kattipparuthi

- Athavanad

- Ummathoor

- Irimbiliyam

- Parudur

- Olakara

- Trikkulam

- Koduvayur

- Vengara

- Kannamangalam

- Oorakam-Melmuri

- Puthur

- Kottakkal

- Indiannur

- Valakkulam[30]

4. Eranad

Eranad was the original headquarters of the Zamorin of Calicut. It was later changed to Kozhikode with the conquest of Polanad. It also was under the direct rule of the Zamorin.[30] It consisted of the following 26 Amsoms:

- Mappram

- Cheekkode

- Urangattiri

- Mampad

- Nilambur

- Porur

- Wandoor

- Thiruvali

- Trikkalangode

- Karakunnu

- Iruvetti

- Kavanoor

- Chengara

- Puliyakode

- Kuzhimanna

- Kolathur

- Nediyiruppu

- Keezhmuri

- Melmuri

- Arimbra

- Valluvambram

- Irumbuzhi

- Manjeri

- Payyanad

- Elankur

- Ponmala[30]

Walluvanad Taluk

The Amsoms included in Walluvanad Taluk was classified into four divisions- Vellatiri (Walluvanad proper), Walluvanad, Nedunganad, and Kavalappara. There were 64 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30]

1. Vellatiri (Walluvanad Proper)

Vellatiri (Walluvanad Proper) was the sole remaining territory of the Walluvanad Raja (Valluvakonathiri), who had once ruled majority of the South Malabar. A major part of Ernad Taluk was under Walluvanad before the expansion of the Ernad in 13th-14th centuries. Some of the Amsoms in this division was part of the Ernad Taluk.[30] It consisted of the following 26 Amsoms:

- Kodur

- Kuruva

- Mankada-Pallipuram

- Mankada

- Valambur

- Karyavattam

- Nenmini

- Melattur

- Vettattur

- Kottoppadam

- Arakurissi

- Tachampara

- Arakkuparamba

- Chethallur

- Angadipuram

- Perinthalmanna

- Puzhakkattiri

- Pang

- Kolathur

- Kuruvambalam

- Pulamantol

- Elamkulam

- Anamangad

- Paral

- Chembrassery

- Pandikkad[30]

2. Walluvanad

The Amsoms in this division was comparatively later acquisition by the Zamorin in the territory of the Walluvanad Raja.[30] It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

- Tuvvur

- Thiruvizhamkunnu

- Thenkara

- Kumaramputhur

- Karimpuzha

- Thachchanattukara

- Aliparamba[30]

3. Nedunganad

Nedunganad had been under the Zamorin for some time. After the disintegration of Perumals of Mahodayapuram, Nedunganad became independent. Later it came under the Zamorin's kingdom.[30] It consisted of the following 27 Amsoms:

- Elambulassery

- Vellinezhi

- Sreekrishnapuram

- Kadampazhipuram

- Kalladikode

- Vadakkumpuram

- Moothedath Madamba

- Thrikkadeeri

- Chalavara

- Cherpulassery

- Naduvattam-Karalmanna

- Kulukkallur

- Chundambatta

- Vilayur

- Pulasseri

- Naduvattam

- Muthuthala

- Perumudiyoor

- Nethirimangalam

- Pallippuram

- Kalladipatta

- Vallapuzha

- Kothakurssi

- Eledath Madamba

- Chunangad

- Mulanjur

- Perur[30]

4. Kavalappara

Kavalappara had its own Nairs, who owed a sort of nominal allegiance both to the Zamorin of Calicut and the Kingdom of Cochin.[30] It consisted of the following 6 Amsoms:

- Mundakkottukurissi

- Panamanna

- Koonathara

- Karakkad

- Kuzhappalli

- Mundamuka[30]

Ponnani Taluk

The Amsoms included in Ponnani Taluk was classified into three divisions- Vettathunad, Koottanad, Chavakkad, and the Island of Chetvai . There were 73 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30]

1. Vettathunad

Vettathunad, also known as the Kingdom of Tanur, was a coastal city-state kingdom in the Malabar Coast. It was ruled by the Vettathu Raja, who was dependent on the Zamorin of Calicut. The Kshatriya family of the Vettathu Rajas became extinct with the death of the last Raja on 24 May 1793. [30] Vettathunad consisted of the following 21 Amsoms:

- Pariyapuram

- Rayirimangalam

- Ozhur

- Ponmundam

- Tanalur

- Niramaruthur

- Trikkandiyur

- Iringavoor

- Klari

- Kalpakanchery

- Melmuri

- Ananthavoor

- Kanmanam

- Thalakkad

- Vettom

- Pachattiri

- Mangalam

- Chennara

- Triprangode

- Pallipuram

- Purathur[30]

2. Koottanad

The second home of the Zamorin of Calicut was Thrikkavil Kovilakam at Ponnani in Koottanad. The Zamorin had control over the Koottanad.[30] It consisted of the following 24 Amsoms:

- Thavanur

- Kalady

- Kodanad

- Melattur

- Chekkod

- Anakkara

- Keezhmuri

- Pothanur

- Eswaramangalam

- Pallaprom

- Ponnani

- Kanjiramukku

- Edappal

- Vattamkulam

- Kumaranellur

- Kothachira

- Nagalassery

- Thirumittacode

- Othalur

- Kappur

- Alamkod

- Pallikkara

- Eramangalam

- Vayilathur[30]

3. Chavakkad

Chavakkad had been under the suzerainity of the Zamorin. [30] It consisted of the following 14 Amsoms:

4. The Island of Chetvai

The Island of Chetvai had been earlier under the suzerainity of the Zamorin, but it came under the possession of the Dutch in 1717. [30] It consisted of the following 7 Amsoms:

Palghat Taluk

The Amsoms included in Palghat Taluk was classified into three divisions- Palghat, Temmalapuram, and Naduvattam. There were 56 Amsoms in the Taluk.[30]

1. Palghat

Palghat was ruled by the Palghat Rajas. Sometime previously to 1757, the Zamorin of Calicut, the Kingdom of Valluvanad, and the Kingdom of Cochin had tried to annex Palghat. Cochin had annexed Chittur region. Walluvanad Raja had a nominal sovereignity overthe Nairs of Kongad, Edathara, and Mannur.[30] Palghat division consisted of the following 23 Amsoms:

- Cheraya

- Kongad

- Mundur

- Kavilpad

- Akathethara

- Puthussery

- Elappally

- Polpully

- Pallatheri

- Puthur

- Koppam

- Yakkara

- Vadakkanthara

- Kodunthirapalli

- Edathara

- Kizhakkumpuram

- Thadukkassery

- Mathur

- Pallanchathanur

- Kannadi

- Kinassery

- Thiruvalathur

- Palathully[30]

2. Temmalapuram

Temmalapuram consisted of the following 10 Amsoms:

- Chulanur

- Vadakkethara

- Kattusseri

- Kavasseri

- Tarur

- Kannanurpattola

- Ayakkad

- Mangalam

- Vadakkencherry

- Chittilamchery[30]

3. Naduvattam

Naduvattam was originally under the Palghat Raja. Later the Zamorin of Calicut annexed Naduvattam into his kingdom.[30] It consisted of the following 23 Amsoms:

- Kottayi

- Mankara

- Kuthanur

- Kuzhalmannam

- Vilayanchathanur

- Thenkurissi

- Thannissery

- Peruvemba

- Koduvayur

- Kakkayur

- Vilayannur

- Manjalur

- Erimayur

- Kunissery

- Pallavur

- Kudallur

- Pallassena

- Vadavannur

- Kizhakkethara

- Padinjarethara

- Vattekkad

- Panangattiri

- Muthalamada[30]

Political and social movements

The district was the venue for many of the Mappila revolts (uprisings against the British East India Company in Kerala) between 1792 and 1921. It is estimated that there were about 830 riots, large and small, during this period. Muttichira revolt, Mannur revolt, Cherur revolt, Manjeri revolt, Wandoor revolt, Kolathur revolt, Ponnani revolt, and Thrikkalur revolt are some important revolts during this period. During 1841-1921 there were more than 86 revolutions against the British officials alone.[36] East India Company made an arrangement to collect revenue through Zamorin. However, a revolt under the leadership of Manjeri Athan Gurukkal took place opposing it in 1849.[37]

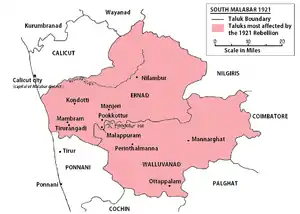

The Malabar district political conference of Indian National Congress held at Manjeri on 28 April 1920 strengthened Indian independence movement and national movement in Malabar District.[38] That conference declared that the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms were not able to satisfy the needs of British India. It also argued for land reform to seek solutions for the problems caused by the tenancy that existed in Malabar. However, the decision widened the drift between extremists and moderates within Congress. The conference resulted in the dissatisfaction of landlords with the Indian National Congress. It caused the leadership of the Malabar district Congress Committee to come under the control of the extremists who stood for labourers and the middle class.[39] Eranad, Valluvanad, and Ponnani Taluks had been part of Khilafat Movement just after the Manjeri conference. The Khilafat non-cooperation demonstration conducted at Kalpakanchery in Ponnani Taluk (now a part of Tirur Taluk) on 22 March 1921 under the leadership of K. P. Kesava Menon was attended by about 20,000 people. The first all Kerala provincial conference of Indian National Congress held at Ottapalam in April 1921 also influenced the rebellion. Malabar Rebellion of 1921 was the last and important among the Mappila rebellions.

The cities/towns of Malappuram, Manjeri, Kondotty, Perinthalmanna, and Tirurangadi were the main strongholds of the rebels. The Battle of Pookkottur occurred as a part of the rebellion. After the army, police, and British authorities fled, the declaration of independence took place in over 200 villages in Eranad, Valluvanad, Ponnani, and Kozhikode taluks.[40] The new country was given the name Malayala Rajyam (The land of Malayalam).[41] On August 25, 1921, Variyan Kunnathu Kunjahammed Haji inaugurated the Military Training Center at Angadipuram, which was started by the revolutionary government. The feudal customs of Kumpil Kanji and Kanabhumi were abolished and the tenants were made landowners. A tax exemption was given for one year and a tax was imposed on the movement of goods from Wayanad to Tamil Nadu.[42] Similar to the British, the structure of administration was built upon Collector, Governor, Viceroy, and King.[43] The parallel government established courts, tax centers, food storage centers, the military, and the legal police. Passport system was introduced for those in the new country.[44] [45] Although the nation's lifespan is less than six months, some British officials have suggested that the region was ruled by a parallel government for more than a year.[46] [47]

The rebels won to establish self-rule in the region for about six months. However less than six months after the declaration of autonomy, the East India Company reclaimed the territory and annexed it to the British Raj. The war was directly controlled by British Army Commander-in-Chief Chief Rawlson, General Barnett Stuart, Intelligence Chief Maurice Williams, and Police General Armitage. Many of the important British military regiments including Dorset, Karen, Yenier, Linston, Rajputana, Gorkha, Garwale, and Chin Kutchin reached Malabar for the reannexation of the South Malabar.[48] The Wagon tragedy (1921) is still a saddening memory of the Malabar rebellion, where 64 prisoners died on 20 November 1921.[49] The prisoners had been taken into custody following the Mappila Rebellion in various parts of the district. Their deaths through apparent negligence generated sympathy for Indian independence movement.

Post-Independence

After the Indian independence, Madras Presidency was reorganized into Madras state, which was divided along linguistic lines on 1 November 1956, when Malabar District was merged with erstwhile Kasaragod Taluk immediately to the north and the state of Travancore-Cochin to the south to form the state of Kerala. Malabar District was divided into the three districts of Kozhikode, Palakkad, and Kannur on 1 January 1957. The Chavakkad region of the Ponnani Taluk was transferred to the Thrissur district. Malappuram District was created from parts of Kozhikode and Palakkad in 1969, and Wayanad District was created in 1980 from parts of Kozhikode and Kannur.

Geography

Malabar district, also known as the Malayalam district, bears its name from the hilly nature of many areas in the district.[1] It was one of the two districts of Madras presidency, which lied in the western coast (Malabar coast) of India, the other being the South Canara. Wayanad, Valluvanad, and Palakkad Taluks hadn't seacoast, whereas the remaining Taluks in the district had coastal areas.[1] With an exception of the Lakshadweep islands, the district was wedged between the Lakshadweep Sea and the Western Ghats. The district was widely scattered and consists of the following parts:-

- Malabar Proper extending north to south along the coast, a distance of around 240 kilometers, and lying between N. Lat 10° 15′ and 12° 18′ N and E.Long. 75° 14′ and 76° 56′.

- A group of nineteen isolated bits of territory lying scattered, fifteen of them in the native state of Cochin and the remaining four in those of Travancore, but all of them near the coastline. These isolated bits of territory form the taluk of British Cochin.

- Two other detached bits of land, the Tangasseri and the Anchuthengu, within the Travancore.

- Four inhabited and ten uninhabited islands of Lakshadweep. The four inhabited islands are: Agatti, Kavaratti, Androth, and Kalpeni.

- The solitary island of Minicoy.

The Western Ghats form a continuous mountain range on the eastern border of the district. Only break in the Ghats was formed by the Palakkad Gap. The western part of the district was sandy coast. The Ghats in the district maintained an average elevation of 1500 m, which might occasionally go up to 2500 m.[1] In Kozhikode Taluk, they turned sharply eastwards and after passing the Nilambur valley in Ernad Taluk, they continued further south along the eastern portions of Ernad and Walluvanad Taluks and the northern portion of Palghat Taluk.[1] Palakkad Gap broke the Ghats in Palghat Taluk. Apart from the main continuous range of Western Ghats, there were many small undulating hills in the lowland of the district.[1] Tropical evergreen forests were present in the mountain ranges in the district.[1]

Two rivers flowed eastwards in the district - Kabini River in Wynad Taluk and Bhavani River in the high hills of the Walluvanad Taluk. Both of them were tributaries of Kaveri.[1] Other rivers in the district were west-flowing which flows into the Arabian Sea. Coastal backwaters like Kavvayi and Biyyam were also there. The important west-flowing rivers included Valapattanam River in Chirakkal Taluk, Anjarakandi River in Kottayam Taluk, Mahé River and Kuttiadi River in Kurumbranad Taluk, Chaliyar in Ernad Taluk, Kadalundi River in Ernad and Walluvanad Taluks, and Bharathappuzha in Ponnani and Palghat Taluks.[1] Other rivers were Kottoor, Irikkur, Vannathi, Pazhayangadi, Perumba, Kuppam, Kuttikol, and Kavvayi in Chirakkal Taluk, Bavali and Iritti in Kottayam Taluk (Bavali flows through Wynad too), Korapuzha in Kurumbranad and Kozhikode Taluks, Panamarampuzha and Manantoddy River in Wynad Taluk, Kallayi, Irittuzhi, Irungi, and Mukkam in Kozhikode Taluk, Thuthapuzha in Ponnani and Walluvanad Taluks, Olipuzha and Siruvani in Walluvanad Taluk, and Kalpathipuzha, Yakkarapuzha, and Gayathripuzha in Palghat Taluk.[1]

Administrative divisions

.svg.png.webp)

Malabar district had 5 revenue divisions namely, Thalassery (Tellicherry), Kozhikode (Calicut), Malappuram, Palakkad (Palghat), and Fort Cochin and 10 Taluks within them.[1]

Thalassery Revenue Division

Headquartered at Thalassery[1]

Taluks

- Chirakkal (Area:1,750 square kilometres (677 sq mi); Headquarters:Chirakkal), now Kannur

- Kottayam (Area:1,270 square kilometres (489 sq mi); Headquarters:Kottayam), now Thalassery

- Wayanad (Area:2,130 square kilometres (821 sq mi); Headquarters:Mananthavady)[1]

Taluks

- Kurumbranad (Area:1,310 square kilometres (505 sq mi); Headquarters:),now Vatakara

- Kozhikode & Laccadive Islands (Area:980 square kilometres (379 sq mi); Headquarters:Kozhikode)

(Laccadive islands were a separate Taluk under British rule. Later it merged with Kozhikode Taluk.)

Malappuram Revenue Division

Headquartered at Malappuram[1]

Taluks

- Ernad (Area:2,540 square kilometres (979 sq mi); Headquarters:Manjeri)

- Valluvanad (Area:2,280 square kilometres (882 sq mi); Headquarters:), now Perinthalmanna[1]

Taluks

Fort Cochin Revenue Division

Headquartered at Fort Cochin[1]

- Cochin (Area:5.2 square kilometres (2 sq mi); Headquarters:Cochin)[1]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 2,261,250 | — |

| 1881 | 2,365,035 | +0.45% |

| 1891 | 2,652,565 | +1.15% |

| 1901 | 2,800,555 | +0.54% |

| 1911 | 3,015,119 | +0.74% |

| 1921 | 3,098,871 | +0.27% |

| 1931 | 3,533,944 | +1.32% |

| 1941 | 3,929,425 | +1.07% |

| 1951 | 4,758,842 | +1.93% |

| Source:[50] | ||

Religion in Malabar District (1951)[51]

The Talukwise area and population of Malabar district as of 1951 Census of India are given below:

| # | Taluk | Area (in sq.miles) |

Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thalassery Division | |||

| 1 | Chirakkal (Kannur) | 688 | 534,890 |

| 2 | Kottayam (Thalassery) | 484 | 369,580 |

| 3 | Wayanad (Mananthavady) | 821 | 169,280 |

| Kozhikode Division | |||

| 4 | Kurumbranad (Vatakara) | 506 | 554,091 |

| 5 | Kozhikode & Laccadive Islands | 380 | 530,364 |

| Malappuram Division | |||

| 6 | Eranad (Manjeri) | 978 | 614,283 |

| 7 | Valluvanad (Perinthalmanna) | 873 | 573,457 |

| Palakkad Division | |||

| 8 | Ponnani | 427 | 793,805 |

| 9 | Palakkad | 643 | 585,651 |

| Fort Cochin Division | |||

| 10 | Fort Cochin | 2 | 32,941 |

| Total | 5,802 | 4,758,842 | |

Towns and Types

Although there were several settlements across Malabar district during the Madras Presidency or Pre-Independence era, only a handful were officially considered as 'Towns'. Those were Cannanore, Tellicherry, Badagara, Calicut, Malappuram, Tanur, Ponnani, Palghat and Fort Kochi.[52]

Abbreviations

| M: Municipality: | Towns with a local governing body constituted under Madras Town Improvement Act of 1865. |

| T: Non Municipal Town: | Towns without a governing body, listed in Madras District Records. |

| C: Cantonment | Towns with a Military base in Madras Presidency. |

| A.C: Administrative Center: | Towns supporting administrative headquarters of higher order. |

| City/Town | Year Declared |

Type | Taluk | Revenue Division | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Independence / Late 1800s | (1881) | ||||

| Kozhikode | 1866 | M, C, AC | Kozhikode | Kozhikode | 57,085 |

| Palakkad | 1866 | M, AC | Palghat | Palghat | 36,339 |

| Thalassery | 1866 | M, AC | Kottayam | Tellicherry | 26,410 |

| Kannur | 1866 | M, C | Chirakkal | Tellicherry | 26,386 |

| Fort Kochi | 1866 | M, AC | Fort Cochin | Fort Cochin | 15,698 |

| Early 1900s | (1901) | ||||

| Badagara | 1902 | T | Kurumbranad | Kozhikode | 11,319 |

| Ponnani | 1902 | T | Ponnani | Palghat | 10,562 |

| Malappuram | 1904 | T, C, AC | Ernad | Malappuram | 9,216 |

| Tanur | 1912 | T | Ponnani | Palghat | 8,409 |

| Mid 1900s | (1941) | ||||

| Pandalayini (Koyilandy) |

1941 | T | Kurumbranad | Kozhikode | 12,713 |

| Feroke | 1941 | T | Ernad | Malappuram | 6,249 |

| Manjeri | 1941 | T | Ernad | Malappuram | 5,547 |

| Trikkandiyur (Tirur) |

1941 | T | Ponnani | Palghat | 9,489 |

1951 Census of India

The settlements with a population of more than 50,000 were considered as cities and those had between 10,000 and 50,000 were considered as towns.[51] The following table gives the cities and towns of Malabar district classified by their population as of the 1951 Census:

| City/Town | Taluk | Population (1951) |

|---|---|---|

| Cities | ||

| Kozhikode | Kozhikode | 158,724 |

| Palakkad | Palghat | 69,504 |

| Towns | ||

| Kannur | Chirakkal | 42,431 |

| Thalassery | Kottayam | 40,040 |

| Fort Kochi | Fort Cochin | 29,881 |

| Panthalayini (Koyilandy) | Kurumbranad | 29,001 |

| Ponnani | Ponnani | 23,606 |

| Ottapalam | Walluvanad | 22,695 |

| Badagara | Kurumbranad | 20,964 |

| Feroke | Ernad | 19,463 |

| Tanur | Ponnani | 17,888 |

| Trikkandiyur (Tirur) | Ponnani | 11,830 |

| Shoranur | Walluvanad | 11,596 |

| Manjeri | Ernad | 10,357 |

| Total | 507,975 | |

Politics

Representatives from Malabar to Madras State

- In C. Rajagopalachari Ministry: 1) Kongattil Raman Menon (1937–39), 2) C. J. Varkey, Chunkath (1939)

- In Prakasam Ministry: 1) R. Raghavamenon (1946–47)

- In Ramaswami Reddyar Ministry: 1) Kozhippurathu Madhavamenon (1947–49)

- In P. S. Kumaraswami Ministry: 1) Kozhippurathu Madhavamenon (1949–52)

- In C. Rajagopalachari Ministry: 1) K. P. Kuttikrishnan Nair (1952–54) Kalladi Unnikammu Sahib

1951–52 Indian general election

In the first election to the Lok Sabha conducted under the provisions of the Indian Constitution after Independence, Malabar district had five constituencies, Kannur, Thalassery, Kozhikode, Malappuram and Ponnani.[57]

| Constituency | Winner | Party | Runner-up | Party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kannur | A. K. Gopalan | CPI | C.K.K Govindan Nayar | INC | ||

| K.S.Subramania Iyer | IND | ||||||

| 2 | Thalassery | Nettur P. Damodaran | KMPP | P. Kunhiraman | INC | ||

| P.M.V Kunhiraman Nambiar | SP | ||||||

| 3 | Kozhikode | Achuthan Damodaran Menon | KMPP | Ummar Koya Parappil | INC | ||

| Ramakrislina Naick,R.N. Ruhur | IND | ||||||

| 4 | Malappuram | B. Pocker Sahib Bahadur | IUML | T.V Chathukutty Nair | INC | ||

| Kumhali Karikedan | CPI | ||||||

| 5 | Ponnani | K. Kelappan | KMPP | Karunakara Menon | INC | ||

| Vella Eacharan Iyyani | INC | Massan Gani | IND | ||||

1952 Madras Legislative Assembly election

25 State Legislative Assembly constituencies were allotted from the Malabar District to the First Assembly of Madras State. 4 of them were dual-member constituencies. The total number of seats in the district was 29 (including dual member constituencies).

| Constituency | Winner | Party | Runner-up | Party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nattika | Gopalakrishnan | CPI | Raman | INC | ||

| 2 | Ponnani | N. Gopala Menon | INC | K. C. Sankarann | INC | ||

| E. T. Kunhan | CPI | A. C. Raman | KMPP | ||||

| 3 | Tirur | K. Uppi Saheb | IUML | K. Ahmad Kutty | INC | ||

| 4 | Thrithala | K. B. Menon | SP | P. K. Moideen Kutty | INC | ||

| 5 | Perinthalmanna | Kunhimahamad Shafee Kallingal | IUML | P. Ahmad Kutty Sadhu | CPI | ||

| 6 | Mannarkkad | K. C. Gopalanunni | IND | Kurikal Ahmed | IND | ||

| 7 | Pattambi | V. Sankara Narayana Menon | KMPP | A. Ramachandra Nedungadi | INC | ||

| 8 | Ottapalam | M. Narayana Kurup | KMPP | C. P. Madhavan Nair | INC | ||

| 9 | Palakkad | K. Ramakrishnan | IND | P. Vasu Menon | INC | ||

| 10 | Alathur | K. Krishnan | CPI | Y. R. Ramanatha Iyer | IND | ||

| O. Koran | KMPP | E. Eacharan | INC | ||||

| 11 | Malappuram | Miniyadam Chadayan | IUML | Karupadata Ibrahim | INC | ||

| Mohammad Haje Seethi | IUML | Kallayan Kunhambu | INC | ||||

| 12 | Kottakkal | Chakkeeri Ahmad Kutty | IUML | Kunjunni Nedumgadi, Ezhuthassan Kalathil | INC | ||

| 13 | Kozhikode | K. P. Kutty Krishnan Nair | INC | E. M. S. Namboodiripad | CPI | ||

| 14 | Chevayur | A. Appu | INC | Ayyadhan Balagopalan | KMPP | ||

| 15 | Wayanad | Manyangode Padmanabha Gounder | SP | Kozhipurath Madhava Menon | INC | ||

| Chomadi Velukkan | SP | Veliyan Nocharamooyal | INC | ||||

| 16 | Koyilandy | Chemmaratha Kunhriramakurup | KMPP | Anantapuram Patinhare Madam Vasudevan Nair | INC | ||

| 17 | Perambra | Kunhiram Kidavu Polloyil | KMPP | Kalandankutty, Puthiyottil | INC | ||

| 18 | Vadakara | Moidu Keloth | SP | Ayatathil Chathu | INC | ||

| 19 | Nadapuram | E. K. Sankara Varma Raja | INC | K. Thacharakandy | CPI | ||

| 20 | Thalassery | C. H. M. Kanaran | CPI | K. P. M. Raghavan Nair | INC | ||

| 21 | Kuthuparamba | Krishna Iyer | IND | Harindranabham, Kalliyat Thazhathuveethil | SP | ||

| 22 | Mattanur | Madhavan Nambiar, Kallorath | CPI | Subbarao | INC | ||

| 23 | Kannur | Kariath Sreedharan | KMPP | Pamban Madhavan | INC | ||

| 24 | Taliparamba | T. C. Narayanan Nambiar | CPI | V. V. Damodaran Nayanar | INC | ||

| 25 | Payyanur | K. P. Gopalan | CPI | Vivekananda Devappa Sernoy | INC | ||

Cuisine

The Malabar cuisine depicts it culture and heritage. It is famous for Malabar biriyani. The city is also famous for Haluva called as Sweet Meat by Europeans due to the texture of the sweet. Kozhikode has a main road in the town named Mittai Theruvu (Sweet Meat Street, or S.M. Street for short). It derived this name from the numerous haluva stores which used to dot the street.

Another speciality is banana chips, which are made crisp and wafer-thin. Other popular dishes include seafood preparations (prawns, mussels, mackerel) . Vegetarian fare includes the sadya.

However, the newer generation is more inclined towards to Chinese and American food. Chinese food is very popular among the locals.

Modern day Taluks and Islands in erstwhile Malabar

| District | Taluk/Island |

|---|---|

| Kasaragod district | Kasaragod |

| Manjeshwaram | |

| Hosdurg | |

| Vellarikundu | |

| Kannur district | Taliparamba |

| Kannur | |

| Payyanur | |

| Thalassery | |

| Iritty | |

| Wayanad district | Mananthavady |

| Sulthan Bathery | |

| Vythiri (Kalpetta) | |

| Kozhikode district | Vatakara |

| Koyilandy | |

| Kozhikode | |

| Thamarassery | |

| Nilgiris district | Gudalur |

| Pandalur | |

| Malappuram district | Tirurangadi |

| Eranad (Manjeri) | |

| Nilambur | |

| Perinthalmanna | |

| Kondotty | |

| Tirur | |

| Ponnani | |

| Palakkad district | Mannarkkad |

| Ottappalam | |

| Palakkad | |

| Pattambi | |

| Alathur | |

| Chittur | |

| Thrissur district | Chavakkad |

| Kodungallur (parts) | |

| Ernakulam district | Fort Kochi |

| Lakshadweep | Agatti |

| Andrott | |

| Bangaram | |

| Kalpeni | |

| Kavaratti | |

| Minicoy |

See also

References

- 1951 census handbook - Malabar district (PDF). Chennai: Government of Madras. 1953. pp. 1–2.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 452.

- Superintendent of Census Operations, Madras (1956). Abstract of 1951 Census Tables for Madras State (PDF). Madras: Government of Madras. p. 6.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. p. 27. ISBN 9788126415885. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Varier, M. R. Raghava. "Documents of Investiture Ceremonies" in K. K. N. Kurup, Edit., "India's Naval Traditions". Northern Book Centre, New Delhi, 1997

- K. V. Krishna Iyer, Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938.

- Ibn Battuta, H. A. R. Gibb (1994). The Travels of Ibn Battuta A.D 1325-1354. IV. London.

- Ma Huan: Ying Yai Sheng Lan, The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores, translated by J.V.G. Mills, 1970 Hakluyt Society, reprint 1997 White Lotus Press. ISBN 974-8496-78-3

- Varthema, Ludovico di, The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, A.D.1503–08, translated from the original 1510 Italian ed. by John Winter Jones, Hakluyt Society, London

- Gangadharan. M., The Land of Malabar: The Book of Barbosa (2000), Vol II, M.G University, Kottayam.

- "Arakkal royal family". Archived from the original on 5 June 2012.

- Charles Corn (1999) [First published 1998]. The Scents of Eden: A History of the Spice Trade. Kodansha America. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-56836-249-6.

- PN Ravindran (2000). Black Pepper: Piper Nigrum. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-5702-453-5. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Philip D. Curtin (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-521-26931-5.

- J. L. Mehta (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: Volume One: 1707–1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 324–327. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Kollam Mayor inspects Tangasseri Fort". The Hindu. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- K. K. N. Kurup (1997). India's Naval Traditions: The Role of Kunhali Marakkars. Northern Book Centre. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-81-7211-083-3. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- South Asia 2006. Taylor & Francis. 1 December 2005. p. 289. ISBN 9781857433180. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- World States Men: Indian Princes Princely states of India

- V. V., Haridas. "King court and culture in medieval Kerala – The Zamorins of Calicut (AD 1200 to AD 1767)". Unpublished PhD Thesis. Mangalore University

- Madrass District Gazetteers, The Nilgiris. By W. Francic. Madras 1908 Pages 90-104

- Report of the Administration of Mysore 1863-64. British Parliament Library

- British Museum; Anna Libera Dallapiccola (22 June 2010). South Indian Paintings: A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection. Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-0-7141-2424-7. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Edgar Thorpe, Showick Thorpe; Thorpe Edgar. The Pearson CSAT Manual 2011. Pearson Education India. p. 99. ISBN 978-81-317-5830-4. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- The Edinburgh Gazetteer. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1827. pp. 63–. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Dharma Kumar (1965). Land and Caste in South India: Agricultural Labor in the Madras Presidency During the Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive. pp. 87–. GGKEY:T72DPF9AZDK. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- K.P. Ittaman (1 June 2003). History of Mughal Architecture Volume Ii. Abhinav Publications. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-81-7017-034-1. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- C.A., Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers: Malabar and Anjengo. Government Press, Madras. p. 373. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- C.A., Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers: Malabar and Anjengo. Government Press, Madras. p. 416. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Logan, William (2010). Malabar Manual (Volume-I). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 631–666. ISBN 9788120604476.

- Sreenivasa Murthy, H. V. (1990). Essays on Indian History and Culture: Felicitation Volume in Honour of Professor B. Sheik Ali. ISBN 9788170992110.

- Logan, William (1887). Malabar Manual (Volume-2). Madras: PRINTED BY R. HILL, AT THE GOVERNMENT PRESS.

- Ayyappan, A. (1992). The Paniyas: An Ex-slave Tribe of South India. The University of Michigan: Institute of Social Research and Applied Anthropology. pp. 20, 28–29, 80.

- Kurup, Dr. K K N (2008). Jain society of Wayanad, Sri Ananthanatha Swami Kshetram, Kalpetta, Platinum Jubilee souvenir. p. 45.

- Rice, B. Lewis (1902). Epigraphica Carnatica (PDF). Mangalore: Government of India. pp. 24, 28, 32.

- K. Madhavan Nair, 'Malayalathile Mappila Lahala,' Mathrubhumi, 24 March 1923.

- "History of Malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "The 1920 political conference at Manjeri". Deccan Chronicle. 29 June 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (2007). A Survey of Kerala History (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- Malabar Desiyathayude Idapedalukal. Dr. M. T. Ansari. DC Books

- R. H. Hitch cock, 1983 Peasant revolt in Malabar, History of Malabar Rebellion 1921.

- Madras Mail 17 September 1921, p 8

- ‘particularly strong evidence of the molding influence of British power structures lies in the rebels constant use of British titles to authority such as Assistant Inspector, Collector, Governor, Viceroy and (less conclusively) King’ The Moplah Rebellion and Its Genesis 184

- ‘The rebel kists’, martial law, tolls, passports and, perhaps, the concept of a Pax Mappila, are to all appearances traceable to the British empire in India as a prototype’ The Moplah Rebellion and Its Genesis, Peoples Publishing House, 1987, 183

- C. Gopalan Nair. Moplah Rebellion, 1921. p. 78. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

He issued passports to persons wishing to get outside his kingdom

- F. B. Evans, ‘Notes on the Moplah Rebellion’, 27 March 1922, p 12.

- (Tottenham, G. F. R., ‘Summary of the Important Events of the Rebellion,’ in Tottenham, Mapilla Rebellion) 1921 dated Sept 15 no 367

- Home (Pol) Department, Government of India, File No. 241/XVI,/1922, Telegram Section, p.3, TNA

- Panikkar, K. N., Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar 1836-1921

- Official Administration of the Madras Presidency, Pg 327

- 1951 census handbook - Malabar district (PDF). Chennai: Government of Madras. 1953.

- Presidency, Madras (India (1915). Madras District Gazetteers, Statistical Appendix For Malabar District (Vol.2 ed.). Madras: The Superintendent, Government Press. p. 20. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Lewis McIver, G. Stokes (1883). Imperial Census of 1881 Operations and Results in the Presidency of Madras ((Vol II) ed.). Madras: E.Keys at the Government Press. p. 444. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Presidency, Madras (India (1915). Madras District Gazetteers, Statistical Appendix For Malabar District (Vol.2 ed.). Madras: The Superintendent, Government Press. p. 20. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- HENRY FROWDE, M.A., Imperial Gazetteer of India (1908–1909). Imperial Gazetteer of India (New ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 2 December 2020.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Devassy, M. K. (1965). District Census Handbook (2) - Kozhikode (1961) (PDF). Ernakulam: Government of Kerala. pp. 11-17 (Part-B).

- Report on the First General Elections in India, 1951-1952 (Vol.II ed.). Election Commission. 1955. pp. 54–55. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

Further reading

- S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942), Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language, University of Madras, retrieved 3 December 2020

- Government of Madras (1953), 1951 Census Handbook- Malabar District (PDF), Madras Government Press, retrieved 3 December 2020