Indometacin

Indometacin, also known as indomethacin, is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) commonly used as a prescription medication to reduce fever, pain, stiffness, and swelling from inflammation. It works by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, endogenous signaling molecules known to cause these symptoms. It does this by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, an enzyme that catalyzes the production of prostaglandins.[1][2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɪndoʊˈmɛtəsɪn/ |

| Trade names | Indocid, Indocin |

| Other names | Indomethacin (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, rectal, intravenous, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100% (oral), 80–90% (rectal) |

| Protein binding | 99%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2.6-11.2 hours (adults), 12-28 hours (infants)[1] |

| Excretion | Renal (60%), fecal (33%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.170 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

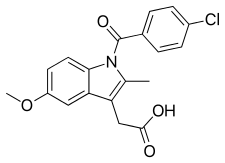

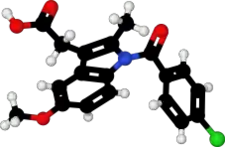

| Formula | C19H16ClNO4 |

| Molar mass | 357.79 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

It was patented in 1961 and approved for medical use in 1963.[3][4] It is marketed under more than twelve different trade names.[5] In 2017, it was the 291st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[6][7]

Medical uses

As an NSAID, indometacin is an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic. Clinical indications for indometacin include:

Joint diseases

- rheumatoid arthritis[8]

- ankylosing spondylitis[8]

- osteoarthritis[8]

- gouty arthritis[8]

- acute painful shoulder bursitis or tendinitis[8]

Headaches

- Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias[9]

- Paroxysmal hemicranias[9]

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania[9]

- Episodic paroxysmal hemicrania[9]

- Hemicrania continua[9]

- Valsalva-induced headaches[9]

- Primary cough headache[9]

- Primary exertional headache[9]

- Primary headache associated with sexual activity (preorgasmic and orgasmic)[9]

- Primary stabbing headache (jabs and jolts syndrome)[9]

- Hypnic headache[9]

Others

Contraindications

- Concurrent peptic ulcer, or history of ulcer disease

- Allergy to indometacin, aspirin, or other NSAIDs

- Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and gastric sleeve patients

- Patients with nasal polyps reacting with an angioedema to other NSAIDs

- Children under 2 years of age (with the exception of neonates with patent ductus arteriosus)

- Severe pre-existing renal and liver damage

- Caution: pre-existing bone marrow damage (frequent blood cell counts are indicated)

- Caution: bleeding tendencies of unknown origin (indometacin inhibits platelet aggregation)

- Caution: Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, psychotic disorders (indometacin may worsen these conditions)[11]

- Concurrent with potassium sparing diuretics

- Patients who have a patent ductus arteriosus dependent heart defect (such as transposition of the great vessels)

- Significant hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Concomitant administration of lithium salts (such as lithium carbonate)

Adverse effects

In general, adverse effects seen with indometacin are similar to all other NSAIDs. For instance, indometacin inhibits both cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2, which then inhibits the production of prostaglandins in the stomach and intestines responsible for maintaining the mucous lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Indometacin, therefore, like other non-selective COX inhibitors, can cause peptic ulcers. These ulcers can result in serious bleeding or perforation, requiring hospitalization of the patient.

To reduce the possibility of peptic ulcers, indometacin should be prescribed at the lowest dosage needed to achieve a therapeutic effect, usually between 50 and 200 mg/day. It should always be taken with food. Nearly all patients benefit from an ulcer protective drug (e.g. highly dosed antacids, ranitidine 150 mg at bedtime, or omeprazole 20 mg at bedtime). Other common gastrointestinal complaints, including dyspepsia, heartburn and mild diarrhea are less serious and rarely require discontinuation of indometacin.

Many NSAIDs, but particularly indometacin, cause lithium retention by reducing its excretion by the kidneys. Thus indometacin users have an elevated risk of lithium toxicity. For patients taking lithium (e.g. for treatment of depression or bipolar disorder), less toxic NSAIDs such as sulindac or aspirin are preferred.

All NSAIDs, including indometacin, also increase plasma renin activity and aldosterone levels, and increase sodium and potassium retention. Vasopressin activity is also enhanced. Together these may lead to:

- Edema (swelling due to fluid retention)

- Hyperkalemia (high potassium levels)[12]

- Hypernatremia (high sodium levels)

- Hypertension

Elevations of serum creatinine and more serious renal damage such as acute kidney failure, chronic nephritis and nephrotic syndrome, are also possible. These conditions also often begin with edema and high potassium levels in the blood.

Paradoxically yet uncommonly, indometacin can cause headache (10 to 20%), sometimes with vertigo and dizziness, hearing loss, tinnitus, blurred vision (with or without retinal damage). There are unsubstantiated reports of worsening Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, and psychiatric disorders. Cases of life-threatening shock (including angioedema, sweating, severe hypotension and tachycardia as well as acute bronchospasm), severe or lethal hepatitis and severe bone marrow damage have all been reported. Skin reactions and photosensitivity are also possible side effects.

The frequency and severity of side effects and the availability of better tolerated alternatives make indometacin today a drug of second choice. Its use in acute gout attacks and in dysmenorrhea is well-established because in these indications the duration of treatment is limited to a few days only, therefore serious side effects are not likely to occur.

People should undergo regular physical examination to detect edema and signs of central nervous side effects. Blood pressure checks will reveal development of hypertension. Periodic serum electrolyte (sodium, potassium, chloride) measurements, complete blood cell counts and assessment of liver enzymes as well as of creatinine (renal function) should be performed. This is particularly important if Indometacin is given together with an ACE inhibitor or with potassium-sparing diuretics, because these combinations can lead to hyperkalemia and/or serious kidney failure. No examinations are necessary if only the topical preparations (spray or gel) are applied.

Rare cases have shown that use of this medication by pregnant women can have an effect on the fetal heart, possibly resulting in fetal death via premature closing of the Ductus arteriosus.[13]

In October 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the drug label to be updated for all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications to describe the risk of kidney problems in unborn babies that result in low amniotic fluid.[14][15] They recommend avoiding NSAIDs in pregnant women at 20 weeks or later in pregnancy.[14][15]

Mechanism of action

Indometacin, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), has similar mode of action when compared to other drugs in this group. It is a nonselective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 and 2, the enzymes that participate in prostaglandin synthesis from arachidonic acid. Prostaglandins are hormone-like molecules normally found in the body, where they have a wide variety of effects, some of which lead to pain, fever, and inflammation. By inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins, indometacin can reduce pain, fever, and inflammation.[8] Indometacin mechanism of action, along with several other NSAIDs that inhibit COX, was described in 1971.[16]

Besides, indometacin has logarithmic acid dissociation constant pKa of 3 to 4.5. Since the physiologic body pH is well above the pKa range of indometacin, most of the indometacin molecules will be dissociated into ionized form, leaving very little un-ionized form of indometacin to cross a cell membrane. If the pH gradient across a cell membrane is high, most of the indometacin molecules will be trapped in one side of the membrane with higher pH. This phenomenon is called "ion trapping". The phenomenon of ion trapping is particularly prominent in the stomach as pH at the stomach mucosa layer is extremely acidic, while the parietal cells are more alkaline. Therefore, indometacin are trapped inside the parietal cells in ionized form, damaging the stomach cells, causing stomach irritation. This stomach irritation can reduce if the stomach acid pH is reduced.[8]

Indometacin's role in treating certain headaches is unique compared to other NSAIDs. In addition to the class effect of COX inhibition, there is evidence that indometacin has the ability to reduce cerebral blood flow not only through modulation of nitric oxide pathways but also via intracranial precapillary vasoconstriction.[17] Indometacin property of reducing cerebral blood flow is useful in treating raised intracranial pressure. A case report has shown that an intravenous bolus dose of indometacin given with 2 hours of continuous infusion is able to reduce intracranial pressure by 37% in 10 to 15 minutes and increases cerebral perfusion pressure by 30% at the same time.[8] This reduction in cerebral pressure may be responsible for the remarkable efficacy in a group of headaches that is referred to as "indometacin-responsive headaches", such as idiopathic stabbing headache, chronic paroxysmal hemicranial, and exertional headaches.[18] On the other hand, the activation of superior salivary nucleus in the brainstem is used to stimulate the trigeminal autonomic reflex arc, causing a type of headache called trigeminal autonomic cephalgia. Indometacin inhibits the superior salivatory nucleus, thus relieving this type of headache.[8]

Prostaglandins also cause uterine contractions in pregnant women. Indometacin is an effective tocolytic agent,[19] able to delay premature labor by reducing uterine contractions through inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in the uterus and possibly through calcium channel blockade.

Indometacin readily crosses the placenta and can reduce fetal urine production to treat polyhydramnios. It does so by reducing renal blood flow and increasing renal vascular resistance, possibly by enhancing the effects of vasopressin on the fetal kidneys.

Other modes of action for indometacin are:

- it inhibits motility of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, similar to colchicine

- it uncouples oxidative phosphorylation in cartilaginous (and hepatic) mitochondria, like salicylates

- it has been found to specifically inhibit MRP (multidrug resistance proteins) in murine and human cells[20]

Nomenclature

Indometacin is the INN, BAN, and JAN of the drug while indomethacin is the USAN, and former AAN and BAN.[21][22][23]

References

- Brayfield A, ed. (14 January 2014). "Indometacin". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- "TGA Approved Terminology for Medicines, Section 1 – Chemical Substances" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government. July 1999: 70. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hart FD, Boardman PL (October 1963). "Indomethacin: A New Non-steroid Anti-inflammatory Agent". British Medical Journal. 2 (5363): 965–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5363.965. PMC 1873102. PMID 14056924.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 517. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Trade names are listed on DrugBank.ca entry DB00328

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Indomethacin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Lucas S (February 2016). "The Pharmacology of Indomethacin". Headache. 56 (2): 436–46. doi:10.1111/head.12769. PMID 26865183. S2CID 205160729.

- Dodick DW (February 2004). "Indomethacin-responsive headache syndromes". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 8 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1007/s11916-004-0036-6. PMID 14731379. S2CID 24393617.

- Sekar KC, Corff KE (May 2008). "Treatment of patent ductus arteriosus: indomethacin or ibuprofen?". Journal of Perinatology. 28 Suppl 1: S60-2. doi:10.1038/jp.2008.52. PMID 18446180.

- "INDOMETHACIN". Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB). National Library of Medicine's TOXNET. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Akbarpour F, Afrasiabi A, Vaziri ND (June 1985). "Severe hyperkalemia caused by indomethacin and potassium supplementation". Southern Medical Journal. 78 (6): 756–7. doi:10.1097/00007611-198506000-00039. PMID 4002013.

- Enzensberger C, Wienhard J, Weichert J, Kawecki A, Degenhardt J, Vogel M, Axt-Fliedner R (August 2012). "Idiopathic constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus: three cases and review of the literature". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 31 (8): 1285–91. doi:10.7863/jum.2012.31.8.1285. PMID 22837295. S2CID 6798504.

- "FDA Warns that Using a Type of Pain and Fever Medication in Second Half of Pregnancy Could Lead to Complications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "NSAIDs may cause rare kidney problems in unborn babies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Ferreira SH, Moncada S, Vane JR (June 1971). "Indomethacin and aspirin abolish prostaglandin release from the spleen". Nature. 231 (25): 237–9. doi:10.1038/newbio231237a0. PMID 5284362.

- Castellano AE, Micieli G, Bellantonio P, Buzzi MG, Marcheselli S, Pompeo F, Rossi F, Nappi G (November 1998). "Indomethacin increases the effect of isosorbide dinitrate on cerebral hemodynamic in migraine patients: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications". Cephalalgia : An International Journal of Headache. 18 (9): 622–30. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1809622.x. PMID 9876886.

- Dowd FJ, Johnson B, Mariotti A. "Chapter 23, Drugs for Treating Orofacial Pain Syndromes.". Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry-E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2016 Sep 3. pp. 384–5.

- Giles W, Bisits A (October 2007). "Preterm labour. The present and future of tocolysis". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 21 (5): 857–68. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.03.011. PMID 17459777.

- Draper MP, Martell RL, Levy SB (1997). "Indomethacin-mediated reversal of multidrug resistance and drug efflux in human and murine cell lines overexpressing MRP, but not P-glycoprotein". British Journal of Cancer. 75 (6): 810–5. doi:10.1038/bjc.1997.145. PMC 2063393. PMID 9062400.

- Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 684–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 550–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

External links

- Effects of Perinatal Indomethacin Treatment on Preterm Infants, academic dissertation (PDF)

- Indomethacin, from MedicineNet

- Indomethacin, from Drugs.com

- Indocin: Description, chemistry, ingredients, from RxList.com