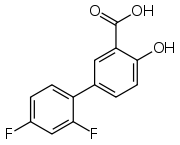

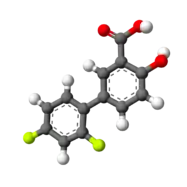

Diflunisal

Diflunisal is a salicylic acid derivative with analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity.[1] It was developed by Merck Sharp & Dohme in 1971, as MK647, after showing promise in a research project studying more potent chemical analogs of aspirin.[2] It was first sold under the brand name Dolobid, marketed by Merck & Co., but generic versions are now widely available. It is classed as a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and is available in 250 mg and 500 mg tablets.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684037 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80-90% |

| Protein binding | >99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 8 to 12 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.040.925 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H8F2O3 |

| Molar mass | 250.201 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Mechanism of action

Like all NSAIDs, diflunisal acts by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins,[3] hormones which are involved in inflammation and pain. Diflunisal also has an antipyretic effect, but this is not a recommended use of the drug.[4]

It has been found to inhibit p300 and CREB-binding protein (CBP), which are epigenetic regulators that control the levels of proteins that cause inflammation or are involved in cell growth.[5]

It has been reported that diflunisal has some antibacterial activity in vitro against Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS).[6]

Duration of effect

Though diflunisal has an onset time of 1 hour, and maximum analgesia at 2 to 3 hours, the plasma levels of diflunisal will not be steady until repeated doses are taken.[4] The long plasma half-life is a distinctive feature of diflunisal in comparison to similar drugs. To increase the rate at which the diflunisal plasma levels become steady, a loading dose is usually used. It is primarily used to treat symptoms of arthritis,[7] and for acute pain following oral surgery, especially removal of wisdom teeth.[8]

Effectiveness of diflunisal is similar to other NSAIDs, but the duration of action is twelve hours or more. This means fewer doses per day are required for chronic administration. In acute use, it is popular in dentistry when a single dose after oral surgery can maintain analgesia until the patient is asleep that night.

Medical uses

- Pain, mild to moderate

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Injury to tendons

- Inflammation

- ATTR amyloidosis

Amyloidosis

Both diflunisal[9][10] and several of its analogues[11] have been shown to be inhibitors of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis, a disease which currently has few treatment options. Phase I trials have shown the drug to be well tolerated,[12] with a small Phase II trial (double-blind, placebo-controlled, 130 patients for 2 years) in 2013 showing a reduced rate of disease progression and preserved quality of life.[13] However a significantly larger Phase III trial would be needed to prove the drugs effectiveness for treating this condition.

Side effects

In October 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the drug label to be updated for all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications to describe the risk of kidney problems in unborn babies that result in low amniotic fluid.[14][15] They recommend avoiding NSAIDs in pregnant women at 20 weeks or later in pregnancy.[14][15]

Gastrointestinal

The inhibition of prostaglandins has the effect of decreasing the protection given to the stomach from its own acid. Like all NSAIDS, this leads to an increased risk of stomach ulcers, and their complications, with long-term use. Elderly users of diflunisal are at greater risk for serious GI events.

- Increased risk of GI events including bleeding, ulceration, and stomach or intestine perforation.

- Abdominal pain or cramps

- Constipation

- Gas

- Diarrhea

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dyspepsia

Cardiovascular

- Irregular heart beat

- Possible increased risk of serious and potentially fatal cardiovascular thrombotic events, MI, and stroke

- Risks may increase with duration of use and for cardiovascular disease history

Ear, nose, throat, and eye

- Ringing in the ears

- Yellowing of eyes

Central nervous system

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Insomnia

- Fatigue

- Somnolence

- Nervousness

Skin

- Swelling of the feet, ankles, lower legs, and hands

- Yellowing of skin

- Rash

- Ecchymosis

Contraindications

- Hypersensitivity to aspirin/NSAID-induced asthma or urticaria

- Aspirin triad

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Coronary artery bypass surgery (peri-op pain)

Cautions

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Cardiac risk factors

- Hypertension

- Congestive heart failure

- Elderly or debilitated

- Impaired liver function

- Impaired kidney function

- Dehydration

- Fluid retention

- History of gastrointestinal bleeds/PUD

- Asthma

- Coagulopathy

- Smoker (tobacco use)

- Corticosteriod use

- Anticoagulant use

- Alcohol use

- Diuretic use

- ACE inhibitor use

Overdose

Deaths that have occurred from diflunisal usually involved mixed drugs and or extremely high dosage. The oral LD50 is 500 mg/kg. Symptoms of overdose include coma, tachycardia, stupor, and vomiting. The lowest dose without the presence of other medicines which caused death was 15 grams. Mixed with other medicines, a death at 7.5 grams has also occurred. Diflunisal usually comes in 250 or 500 mg, making it relatively hard to overdose by accident.

References

- Boullard O, Leblanc H, Besson B (2012). "Salicylic Acid". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_477.

- Adams SS (1999). "Ibuprofen, the propionics and NSAIDs: personal reflections over four decades". Inflammopharmacology. 7 (3): 191–7. doi:10.1007/s10787-999-0002-3. PMID 17638090. S2CID 11074565.

- Wallace JL (October 2008). "Prostaglandins, NSAIDs, and gastric mucosal protection: why doesn't the stomach digest itself?". Physiological Reviews. 88 (4): 1547–65. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2008. PMID 18923189.

- Tempero KF, Cirillo VJ, Steelman SL (February 1977). "Diflunisal: a review of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, drug interactions, and special tolerability studies in humans". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 4 Suppl 1: 31S–36S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1977.tb04511.x. PMC 1428837. PMID 328032.

- New Metabolic Pathway Reveals Aspirin-Like Compound’s Anti-Cancer Properties. June 2016

- Jayamani E, Tharmalingam N, Rajamuthiah R, Coleman JJ, Kim W, Okoli I, et al. (September 2017). "Characterization of a Francisella tularensis-Caenorhabditis elegans Pathosystem for the Evaluation of Therapeutic Compounds". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 61 (9). doi:10.1128/AAC.00310-17. PMC 5571314. PMID 28652232.

- Brogden RN, Heel RC, Pakes GE, Speight TM, Avery GS (February 1980). "Diflunisal: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in pain and musculoskeletal strains and sprains and pain in osteoarthritis". Drugs. 19 (2): 84–106. doi:10.2165/00003495-198019020-00002. PMID 6988202. S2CID 24191409.

- Lawton GM, Chapman PJ (August 1993). "Diflunisal--a long-acting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. A review of its pharmacology and effectiveness in management of postoperative dental pain". Australian Dental Journal. 38 (4): 265–71. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.1993.tb05494.x. PMID 8216032.

- Tojo K, Sekijima Y, Kelly JW, Ikeda S (December 2006). "Diflunisal stabilizes familial amyloid polyneuropathy-associated transthyretin variant tetramers in serum against dissociation required for amyloidogenesis". Neuroscience Research. 56 (4): 441–9. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2006.08.014. PMID 17028027. S2CID 42504073.

- Kingsbury JS, Laue TM, Klimtchuk ES, Théberge R, Costello CE, Connors LH (May 2008). "The modulation of transthyretin tetramer stability by cysteine 10 adducts and the drug diflunisal. Direct analysis by fluorescence-detected analytical ultracentrifugation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (18): 11887–96. doi:10.1074/jbc.M709638200. PMC 2335343. PMID 18326041.

- Adamski-Werner SL, Palaninathan SK, Sacchettini JC, Kelly JW (January 2004). "Diflunisal analogues stabilize the native state of transthyretin. Potent inhibition of amyloidogenesis". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 47 (2): 355–74. doi:10.1021/jm030347n. PMID 14711308.

- Berk JL, Suhr OB, Sekijima Y, Yamashita T, Heneghan M, Zeldenrust SR, et al. (June 2012). "The Diflunisal Trial: study accrual and drug tolerance". Amyloid. 19 Suppl 1 (S1): 37–8. doi:10.3109/13506129.2012.678509. PMID 22551208. S2CID 40303434.

- Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, Sekijima Y, Zeldenrust SR, Yamashita T, et al. (December 2013). "Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial". JAMA. 310 (24): 2658–67. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.283815. PMC 4139164. PMID 24368466.

- "FDA Warns that Using a Type of Pain and Fever Medication in Second Half of Pregnancy Could Lead to Complications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "NSAIDs may cause rare kidney problems in unborn babies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links

- Diflunisal: MedlinePlus Drug Information

- Dolobid Prescribing Information (manufacturer's website)

- Dolobid Medication Guide (manufacturer's website)

- "Single dose oral diflunisal for acute postoperative pain in adults"