History of U.S. foreign policy, 1897–1913

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1897 to 1913 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the Presidency of William McKinley, Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, and Presidency of William Howard Taft. The period began with the inauguration of McKinley in 1897 and continued until the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson and the 1914 outbreak of World War I, which marked the start of new era in U.S. foreign policy.

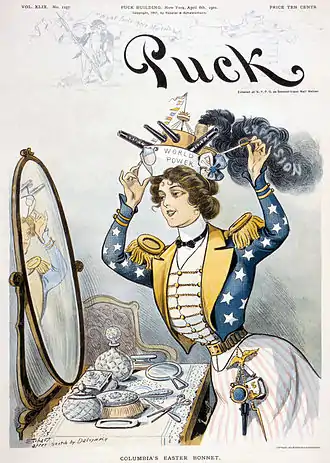

During this era, the United States emerged as a great power that was active even outside of its traditional area of concern in the Western Hemisphere. Major events included the Spanish–American War, the permanent annexation of Hawaii, the temporary annexation of the Philippines, the annexation of Puerto Rico, the Roosevelt Corollary regarding oversight of Latin America, the building of the Panama Canal and the voyage of the Great White Fleet that showed the world the powerful rebuilt U.S. Navy. For the previous history see History of U.S. foreign policy, 1861–1897. For the later period see History of U.S. foreign policy, 1913–1933.

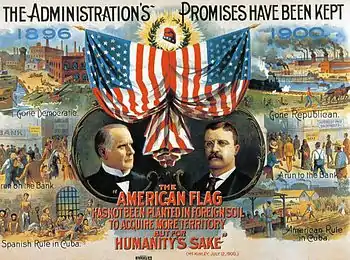

The Cuban War of Independence against Spain broke out in 1895, and many Americans demanded American intervention in the war to stop Spanish cruelty. The business community and top GOP leaders held back. The issue took highest priority when the USS Maine exploded and sank in Havana harbor while on a peace mission. McKinley demanded Spain soften its Cuban controls and Madrid refused. McKinley turned the issue over to Congress, which promptly declared war in April 1898. The United States quickly defeated Spain in the Spanish–American War, taking control of the Spanish possessions of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. In the aftermath of the war, Cuba became a de facto U.S. protectorate and the U.S. put down the Philippine Insurrection. Because of Democratic opposition in the Senate McKinley could not get a 2/3 majority to ratify a treaty to annex Hawaii, so he accomplished the same result by a majority vote on the Newlands Resolution in 1898. The result was a major strategic base in the Pacific Ocean. The McKinley administration thus established the first overseas empire in American history.

President Roosevelt was determined to continue the expansion of U.S. influence, and he placed an emphasis on modernizing the small Army and greatly expanding the large Navy. Roosevelt presided over a rapprochement with Britain and promulgated the Roosevelt Corollary, which held that the United States would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries in order to forestall direct European intervention. Partly as a result of the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States would engage in a series of interventions in Latin America known as the Banana Wars. After Colombia rejected a treaty granting the U.S. a lease across the isthmus of Panama, Roosevelt supported the secession of Panama and subsequently signed a treaty with Panama establishing the Panama Canal Zone. The Panama Canal was completed in 1914, greatly reducing transport time between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. Roosevelt's well publicized actions were widely applauded. President Taft acted quietly, and pursued a policy of "Dollar Diplomacy", emphasizing the use of U.S. financial power in Asia and Latin America. Taft had little success.

The Open Door Policy under President McKinley and Secretary of State John Hay guided U.S. policy towards China, as they sought to keep open trade equal trade opportunities in China for all countries. Roosevelt mediated the peace that ended the Russo-Japanese War and reached the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 limiting Japanese immigration. Roosevelt and Taft sought to mediate and arbitrate other disputes, and in 1906 Roosevelt helped resolve the First Moroccan Crisis by attending the Algeciras Conference. The Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, and the handling of unrest at the border would test the Taft administration before escalating under Wilson.

Leadership

McKinley administration

McKinley took office in 1897 after defeating William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election. McKinley's most unfortunate cabinet appointment was that of elderly Senator John Sherman as secretary of state in order to open a Senate seat for his campaign manager Mark Hanna.[1] Sherman's mental incapacity became increasingly apparent after he took office. He was often bypassed by his first assistant, McKinley's crony William R. Day, and by the second secretary, Alvey A. Adee. Day, an Ohio lawyer unfamiliar with diplomacy, was often reticent in meetings; Adee was somewhat deaf. One diplomat characterized the arrangement, "the head of the department knew nothing, the first assistant said nothing, and the second assistant heard nothing".[2] McKinley asked Sherman to resign in 1898, and Day became the new secretary of state. Later that year, Day was succeeded by John Hay, a veteran diplomat who had served as assistant secretary of state in the Hayes Administration.[3] Leadership of the Navy Department went to former Massachusetts Congressman John Davis Long, an old colleague of McKinley's from his time serving in the House of the Representatives.[4] Although McKinley was initially inclined to allow Long to choose his own the assistant secretary of the navy, there was considerable pressure on the president-elect to appoint Theodore Roosevelt, the head of the New York City Police Commission.[5] The position of secretary of war went to Russell A. Alger, a former general who had also served as the governor of Michigan. Competent enough in peacetime, Alger proved inadequate once the Spanish–American War began. With the War Department plagued by scandal, Alger resigned at McKinley's request in mid-1899 and was succeeded by Elihu Root.[6]

Roosevelt administration

McKinley was assassinated in September 1901 and was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt came into office without any particular domestic policy goals, broadly adhering to most Republican positions on economic issues. He had stronger views on the particulars of his foreign policy, as he wanted the United States to assert itself as a great power in international relations.[7] Anxious to ensure a smooth transition, Roosevelt convinced the members of McKinley's cabinet, most notably Secretary of State John Hay and Secretary of the Treasury Lyman J. Gage, to remain in office.[8] Another holdover from McKinley's cabinet, Secretary of War Elihu Root, had been a Roosevelt confidante for years, and he continued to serve as President Roosevelt's close ally.[9] Root returned to the private sector in 1904 and was replaced by William Howard Taft, who had previously served as the governor-general of the Philippines.[10] After Hay's death in 1905, Roosevelt convinced Root to return to the Cabinet as secretary of state, and Root remained in office until the final days of Roosevelt's tenure.[11]

Taft administration

Roosevelt did not seek reelection in 1908, but instead gave vigorous support to his secretary of war William Howard Taft. [12] In the 1908 presidential election, Taft easily defeated William Jennings Bryan, who lost to McKinley in 1896 and 1900. [13] Taft asked Secretary of State Root to remain in his position, but Root declined and Taft agreed to his recommendation of Philander C. Knox. [14] Taft trusted Knox, who took full charge of diplomacy. However, Knox had poor relations with the Senate, the media and foreign diplomats.[15][16] Knox restructured the State Department, especially in setting up divisions for geographical areas, including the Far East, Latin America and Western Europe.[17] The department's first in-service training program was established, and appointees spent a month in Washington before going to their posts.[18]

There was broad agreement between Taft and Knox on major foreign policy goals; the U.S. would not interfere in European affairs, and would use force if necessary to uphold the Monroe Doctrine in the Americas. The defense of the Panama Canal, which was still under construction throughout Taft's term (it opened in 1914), guided policy in the Caribbean and Central America. However they differed on the Far East.

Dollar diplomacy

Previous administrations had made efforts to promote American business interests overseas, but Taft went a step further and used the web of American diplomats and consuls abroad to further trade. it was called "Dollar Diplomacy." Such ties, Taft hoped, would promote world peace.[19] Dollar diplomacy was designed to avoid military power and instead use American banking power to create a tangible American interest in China that would limit the scope of the other powers, increase the opportunity for American trade and investment, and help maintain the Open Door of trading opportunities of all nations. Whereas Theodore Roosevelt wanted to conciliate Japan and help it neutralize Russia, Taft and his Secretary of State Philander Knox ignored Roosevelt's policy and his advice. Dollar diplomacy was based on the false assumption that American financial interests could mobilize their potential power, and wanted to do so in East Asia. However the American financial system was not geared to handle international finance, such as loans and large investments, and had to depend primarily on London. The British also wanted an open door in China, but were not prepared to support American financial maneuvers. Finally, the other powers held territorial interests, including naval bases and designated geographical areas which they dominated inside China, while the United States refused anything of the kind. Bankers were reluctant, but Taft and Knox kept pushing them to invest. Most efforts were failures, until finally the United States forced its way into the Hukuang international railway loan. The loan was finally made by an international consortium in 1911, and helped spark a widespread "Railway Protection Movement" revolt against foreign investment that overthrew the Chinese government. The bonds caused no end of disappointment and trouble. As late as 1983, over 300 American investors tried, unsuccessfully, to force the government of China to redeem the worthless Hukuang bonds.[20] When Woodrow Wilson became president in March 1913, he immediately canceled all support for Dollar diplomacy. Historians agree that Taft's Dollar diplomacy was a failure everywhere, In the Far East it alienated Japan and Russia, and created a deep suspicion among the other powers hostile to American motives.[21][22]

Taft avoided involvement in international events such as the Agadir Crisis, the Italo-Turkish War, and the First Balkan War. However, Taft did express support for the creation of an international arbitration tribunal and called for an international arms reduction agreement.[23]

Annexation of Hawaii

Hawaii had long been targeted by expansionists as a potential addition to the United States, and a reciprocity treaty in the 1870s had made the Kingdom of Hawaii a "virtual satellite" of the United States. After Queen Liliʻuokalani announced plans to issue a new constitution designed to restore her power, she was overthrown by the business community, which requested annexation by the United States and eventually established the Republic of Hawaii.[24] President Harrison tried to annex Hawaii, but his term ended before he could win Senate approval of an annexation treaty, and Cleveland withdrew the treaty.[25] Cleveland deeply opposed annexation because of a personal conviction that would not tolerate what he viewed as an immoral action against the little kingdom.[26] Additionally, annexation faced opposition from domestic sugar interests opposed to the importation of Hawaiian sugar, and from some Democrats who opposed acquiring an island with a large non-white population.[27]

Upon taking office, McKinley pursued the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii as one of his top foreign policy priorities.[28] In American hands, Hawaii would serve as a base to dominate much of the Pacific, defend the Pacific Coast, and expand trade with Asia.[29] Republican Congressman William Sulzer stated that "the Hawaiian Islands will be the key that will unlock to us the commerce of the Orient."[30] McKinley stated, "we need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny."[31] President McKinley's position was that Hawaii could never survive on its own. It would quickly be gobbled up by Japan—already a fourth of the islands' population was Japanese. Japan would then dominate the Pacific and undermine American hopes for large-scale trade with Asia.[32] The issue of annexation became a major political issue heatedly debated across the United States, which carried over into the 1900 presidential election. By then the national consensus was in favor of the annexation of both Hawaii and the Philippines.[33] Historian Henry Graff says that in the mid-1890s, "unmistakably, the sentiment at home was maturing with immense force for the United States to join the great powers of the world in a quest for overseas colonies."[34]

The drive for expansion was opposed by a vigorous nationwide anti-expansionist movement, organized as the American Anti-Imperialist League. The anti-imperialists listened to Bryan as well as industrialist Andrew Carnegie, author Mark Twain, sociologist William Graham Sumner, and many older reformers from the Civil War era.[35] The anti-imperialists believed that imperialism violated the fundamental principle that just republican government must derive from "consent of the governed." The anti-imperialist league argued that such activity would necessitate the abandonment of American ideals of self-government and non-intervention—ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence, George Washington's Farewell Address and Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.[36][37] However, the anti-imperialists could not stop the even more energetic forces of imperialism. They were led by Secretary of State Hay, naval strategist Alfred T. Mahan, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Secretary of War Root, and Theodore Roosevelt. These expansionists had vigorous support from newspaper publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, who whipped up popular excitement. Mahan and Roosevelt designed a global strategy calling for a competitive modern navy, Pacific bases, an isthmian canal through Nicaragua or Panama, and, above all, an assertive role for the United States as the largest industrial power.[38] They warned that Japan was sending a warship and was poised to seize an independent Hawaii, and thereby be within range of California—a threat that alarmed the West Coast. The Navy prepared the first plans regarding a war with Japan.[39]

McKinley submitted an annexation treaty in June 1897, but anti-imperialists prevented it from winning the support of two-thirds of the Senate. In mid-1898, during the Spanish–American War, McKinley and his congressional allies made another attempt to win congressional approval of an annexation measure.[40] With McKinley's support, Democratic Representative Francis G. Newlands of Nevada introduced a joint resolution that provided for the annexation of Hawaii. The Newlands Resolution faced significant resistance from Democrats and anti-expansionist Republicans like Speaker of the House Reed, but pressure from McKinley helped the bill win passage by wide margins in both houses of Congress.[41] McKinley signed the Newlands Resolution into law on July 8, 1898.[42] McKinley biographer H. Wayne Morgan notes, "McKinley was the guiding spirit behind the annexation of Hawaii, showing ... a firmness in pursuing it".[42] Congress passed the Hawaiian Organic Act in 1900, establishing the Territory of Hawaii. McKinley appointed Sanford B. Dole, who had served as the president of the Republic of Hawaii from 1894 to 1898, as the first territorial governor.[43]

Spanish–American War

Cuban crisis

By the time McKinley took office, rebels in Cuba had waged an intermittent campaign for freedom from Spanish colonial rule for decades. By 1895, the conflict had expanded to a war for independence. The United States and Cuba enjoyed close trade relations, and the Cuban rebellion adversely affected the American economy which was already weakened by the depression.[44] As rebellion engulfed the island, Spanish reprisals grew ever harsher, and Spanish authorities began removing Cuban families to guarded camps near Spanish military bases.[45] The rebels put high priority on their appeals to the sympathy of ordinary Americans, and public opinion increasingly favored the rebels.[46] President Cleveland had supported continued Spanish control of the island, as he feared that Cuban independence would lead to a racial war or intervention by another European power.[47] McKinley also favored a peaceful approach, but he hoped to convince Spain to grant Cuba independence, or at least to allow the Cubans some measure of autonomy.[48] The United States and Spain began negotiations on the subject in 1897, but it became clear that Spain would never concede Cuban independence, while the rebels and their American supporters would never settle for anything less.[49]

Business interests overwhelmingly gave strong support to McKinley's go-slow policies. Big business, high finance, and Main Street businesses across the country were vocally opposed to war and demanded peace, as the uncertainties of a potentially long, expensive war posed serious threat to full economic recovery. The leading railroad magazine editorialized, "from a commercial and mercenary standpoint it seems peculiarly bitter that this war should come when the country had already suffered so much and so needed rest and peace." The strong anti-war consensus of the business community strengthened McKinley's resolve to use diplomacy and negotiation rather than brute force to end the Spanish tyranny in Cuba.[50] On the other hand, humanitarian sensibilities reached fever pitch as church leaders and activists wrote hundreds of thousands of letters to political leaders, calling for intervention in Cuba. These political leaders in turn pressured McKinley to turn the ultimate decision for war over to Congress.[51]

In January 1898, Spain promised some concessions to the rebels, but when American consul Fitzhugh Lee reported riots in Havana, McKinley obtained Spanish permission to send the battleship USS Maine to Havana to demonstrate American concern.[52] On February 15, the Maine exploded and sank with 266 men killed.[53] Public opinion was disgusted with Spain for losing control of the situation, but McKinley insisted that a court of inquiry determine whether the explosion of the Maine was accidental.[54] Negotiations with Spain continued as the court of inquiry considered the evidence, but on March 20, the court ruled that the Maine was blown up by an underwater mine.[55] As pressure for war mounted in Congress, McKinley continued to negotiate for Cuban independence.[56] Spain refused McKinley's proposals, and on April 11, McKinley turned the matter over to Congress. He did not ask for war, but Congress declared war anyway on April 20, with the addition of the Teller Amendment, which disavowed any intention of annexing Cuba.[57] European powers called on Spain to negotiate and give in; Britain supported the American position.[58] Spain ignored the calls and fought the hopeless war alone in order to defend its honor and keep the monarchy alive.[59]

Historical interpretations of McKinley's role

The overwhelming consensus of observers in the 1890s, and historians ever since, is that an upsurge of humanitarian concern with the plight of the Cubans was the main motivating force that caused the war with Spain in 1898. McKinley put it succinctly in late 1897 that if Spain failed to resolve its crisis, the United States would see “a duty imposed by our obligations to ourselves, to civilization and humanity to intervene with force."[60] Louis Perez states, "Certainly the moralistic determinants of war in 1898 has been accorded preponderant explanatory weight in the historiography."[61] By the 1950s, however, American political scientists began attacking the war as a mistake based on idealism, arguing that a better policy would be realism. They discredited the idealism by suggesting the people were deliberately misled by propaganda and sensationalist yellow journalism. Political scientist Robert Osgood, writing in 1953, led the attack on the American decision process as a confused mix of "self-righteousness and genuine moral fervor," in the form of a "crusade" and a combination of "knight-errantry and national self- assertiveness."[62] Osgood argued:

- A war to free Cuba from Spanish despotism, corruption, and cruelty, from the filth and disease and barbarity of General 'Butcher' Weyler's reconcentration camps, from the devastation of haciendas, the extermination of families, and the outraging of women; that would be a blow for humanity and democracy.... No one could doubt it if he believed – and skepticism was not popular – the exaggerations of the Cuban Junta’s propaganda and the lurid distortions and imaginative lies pervade by the “yellow sheets” of Hearst and Pulitzer at the combined rate of 2 million [newspaper copies] a day.[63]

For much of the 20th century historians and textbooks disparaged McKinley as a weak leader—echoing Roosevelt, who called him spineless. They blamed McKinley for losing control of foreign policy and agreeing to an unnecessary war. A wave of new scholarship in the 1970s, from both right and left, reversed the older interpretation.[64] Robert L. Beisner summed up the new views of McKinley as a strong leader. He said McKinley called for war—not because he was bellicose, but because he wanted:

- what only war could bring—an end to the Cuban rebellion, which outraged his humanitarian impulses, prolonged instability in the economy, destroyed American investments and trade with Cuba, created a dangerous picture of an America unable to master the affairs of the Caribbean, threatened to arouse uncontrollable outburst of jingoism, and diverted the attention of U.S. policymakers from historic happenings in China. Neither spineless nor bellicose, McKinley demanded what seemed to him morally unavoidable and essential to American interests.[65]

Nick Kapur says that McKinley's actions were based on his values of arbitrationism, pacifism, humanitarianism, and manly self-restraint, and not on external pressures.[66] Along similar lines Joseph Fry summarizes the new scholarly appraisals:

- McKinley was a decent, sensitive man with considerable personal courage and great political facility. A master manager of men, he tightly controlled policy decisions within his administration....Fully cognizant of the United States' economic, strategic, and humanitarian interests, he had laid out a "policy" early in his administration that ultimately and logically led to war. If Spain could not quell the rebellion through "civilized" warfare, the United States would have to intervene. In early 1898, the Havana riots, the De Lome letter, the destruction of the Maine, and the Redfield Proctor speech convinced McKinley that the autonomy project had failed and that Spain could not defeat the rebels. He then demanded Cuban independence to end both the suffering on the island and the uncertainty in American political and economic affairs.[67]

Course of the war

The telegraph and the telephone gave McKinley a greater control over the day-to-day management of the war than previous presidents had enjoyed. He set up the first war room and used the new technologies to direct the army's and navy's movements.[68] McKinley did not get along with the Army's commanding general, Nelson A. Miles. Bypassing Miles and Secretary of War Alger, the president looked for strategic advice first from Miles's predecessor, General John Schofield, and later from Adjutant General Henry Clarke Corbin.[69] McKinley presided over an expansion of the Regular Army from 25,000 to 61,000 personnel; including volunteers, a total of 278,000 men served in the Army during the war.[70] McKinley not only wanted to win the war, he also sought to bring North and South together again, as white Southerners enthusiastically supported the war effort, and one senior command went to a former Confederate General. His ideal was a unity with Northerner and Southerner, white and black, fighting together for the United States.[71][72]

Since 1895, the Navy had planned to attack the Philippines if war broke out between the United States and Spain. On April 24, McKinley ordered the Asiatic Squadron under the command of Commodore George Dewey to launch an attack on the Philippines. On May 1, Dewey's force defeated the Spanish navy at the Battle of Manila Bay, destroying Spanish naval power in the Pacific.[73] The next month, McKinley increased the number of troops sent to the Philippines and granted the force's commander, Major General Wesley Merritt, the power to set up legal systems and raise taxes—necessities for a long occupation.[74] By the time the troops arrived in the Philippines at the end of June 1898, McKinley had decided that Spain would be required to surrender the archipelago to the United States. He professed to be open to all views on the subject; however, he believed that as the war progressed, the public would come to demand retention of the islands as a prize of war, and he feared that Japan or possibly Germany might seize the islands.[75]

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean theater, a large force of regulars and volunteers gathered near Tampa, Florida, for an invasion of Cuba. The army faced difficulties in supplying the rapidly expanding force even before they departed for Cuba, but by June, Corbin had made progress in resolving the problems.[76] The U.S. Navy began a blockade of Cuba in April while the Army prepared to invade the island, on which Spain maintained a garrison of approximately 80,000.[77] Disease was a major factor: for every American soldier killed in combat in 1898, seven died of disease. The U.S. Army Medical Corps made great strides in treating tropical diseases.[78] There were lengthy delays in Florida—Colonel William Jennings Bryan spent the entire war there as his militia unit was never sent to combat.[79]

The combat army, led by Major General William Rufus Shafter, sailed from Florida on June 20, landing near Santiago de Cuba two days later. Following a skirmish at Las Guasimas on June 24, Shafter's army engaged the Spanish forces on July 2 in the Battle of San Juan Hill.[80] In an intense day-long battle, the American force was victorious, although both sides suffered heavy casualties.[81] Leonard Wood and Theodore Roosevelt, who had resigned as assistant secretary of the Navy, led the "Rough Riders" into combat. Roosevelt's battlefield exploits would later propel him to the governorship of New York in the fall election of 1898.[82] After the American victory at San Juan Hill, the Spanish Caribbean squadron, which had been sheltering in Santiago's harbor, broke for the open sea. The Spanish fleet was intercepted and destroyed by Rear Admiral William T. Sampson's North Atlantic Squadron in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, the largest naval battle of the war.[83] Shafter laid siege to the city of Santiago, which surrendered on July 17, placing Cuba under effective American control.[84] McKinley and Miles also ordered an invasion of Puerto Rico, which met little resistance when it landed in July.[84] The distance from Spain and the destruction of the Spanish navy made resupply impossible, and the Spanish government—its honor intact after losing to a much more powerful army and navy—began to look for a way to end the war.[85]

Peace treaty

On July 22, the Spanish authorized Jules Cambon, the French Ambassador to the United States, to represent Spain in negotiating peace.[86] The Spanish initially wished to restrict their territorial loss to Cuba, but were quickly forced to recognize that their other possessions would be claimed as spoils of war.[85] McKinley's Cabinet unanimously agreed that Spain must leave Cuba and Puerto Rico, but they disagreed on the Philippines, with some wishing to annex the entire archipelago and some wishing only to retain a naval base in the area. Although public sentiment mostly favored annexation of the Philippines, prominent Democrats like Bryan and Grover Cleveland, along with some intellectuals and older Republicans, opposed annexation. These annexation opponents formed the American Anti-Imperialist League.[87] McKinley ultimately decided he had no choice but to annex the Philippines, because he believed Japan would take control of them if the U.S. did not.[88]

McKinley proposed to open negotiations with Spain on the basis of Cuban liberation and Puerto Rican annexation, with the final status of the Philippines subject to further discussion.[89] He stood firmly in that demand even as the military situation on Cuba began to deteriorate when the American army was struck with yellow fever.[89] Spain ultimately agreed to a ceasefire on those terms on August 12, and treaty negotiations began in Paris in September 1898.[90] The talks continued until December 18, when the Treaty of Paris was signed. The United States acquired Puerto Rico and the Philippines as well as the island of Guam, and Spain relinquished its claims to Cuba; in exchange, the United States agreed to pay Spain $20 million.[91] McKinley had difficulty convincing the Senate to approve the treaty by the requisite two-thirds vote, but his lobbying, and that of Vice President Hobart, eventually saw success, as the Senate voted to ratify the treaty on February 6, 1899 on a 57 to 27 vote.[92] Though a significant bloc of senators opposed the treaty, they were unable to unite behind an alternative to ratification.[93]

Aftermath of the Spanish–American War

Philippines

McKinley refused to recognize the native Filipino government of Emilio Aguinaldo, and relations between the United States and the Aguinaldo's supporters deteriorated after the conclusion of the Spanish–American War.[94] McKinley believed that Aguinaldo represented just a small minority of the Filipino populace, and that benevolent American rule would lead to a peaceful occupation.[95] In February 1899, Filipino and American forces clashed at the Battle of Manila, marking the start of the Philippine–American War.[96] The fighting in the Philippines engendered increasingly vocal criticism from the domestic anti-imperialist movement, as did the continued deployment of volunteer regiments.[97] Under General Elwell Stephen Otis, U.S. forces destroyed the rebel Filipino army, but Aguinaldo turned to guerrilla tactics.[98] McKinley sent a commission led by William Howard Taft to establish a civilian government, and McKinley later appointed Taft as the civilian governor of the Philippines.[99] The Filipino insurgency subsided with the capture of Aguinaldo in March 1901,[100] and largely ended with the capture of Miguel Malvar in 1902.[101]

In remote Southern areas, the Muslim Moros resisted American rule in an ongoing conflict known as the Moro Rebellion,[102] but elsewhere the insurgents came to accept American rule. Roosevelt continued the McKinley policies of removing the Catholic friars (with compensation to the Pope), upgrading the infrastructure, introducing public health programs, and launching a program of economic and social modernization. The enthusiasm shown in 1898-99 for colonies cooled off, and Roosevelt saw the islands as "our heel of Achilles." He told Taft in 1907, "I should be glad to see the islands made independent, with perhaps some kind of international guarantee for the preservation of order, or with some warning on our part that if they did not keep order we would have to interfere again."[103] By then the president and his foreign policy advisers turned away from Asian issues to concentrate on Latin America, and Roosevelt redirected Philippine policy to prepare the islands to become the first Western colony in Asia to achieve self-government.[104] Though most Filipino leaders favored independence, some minority groups, especially the Chinese who controlled much of local business, wanted to stay under American rule indefinitely.[105]

The Philippines was a major target for the progressive reformers. A report to Secretary of War Taft provided a summary of what the American civil administration had achieved. It included, in addition to the rapid building of a public school system based on English teaching:

- steel and concrete wharves at the newly renovated Port of Manila; dredging the River Pasig,; streamlining of the Insular Government; accurate, intelligible accounting; the construction of a telegraph and cable communications network; the establishment of a postal savings bank; large-scale road-and bridge-building; impartial and incorrupt policing; well-financed civil engineering; the conservation of old Spanish architecture; large public parks; a bidding process for the right to build railways; Corporation law; and a coastal and geological survey.[106]

Cuba

Cuba was devastated from the war and from the long insurrection against Spanish rule, and McKinley refused to recognize the Cuban rebels as the official government of the island.[107] Nonetheless, McKinley felt bound by the Teller Amendment, and he established a military government on the island with the intention of ultimately granting Cuba independence. Many Republican leaders, including Roosevelt and possibly McKinley himself, hoped that benevolent American leadership of Cuba would eventually convince the Cubans to voluntarily request annexation after they gained full independence. Even if annexation was not achieved, McKinley wanted to help establish a stable government that could resist European interference and would remain friendly to U.S. interests.[108] With input from the McKinley administration, Congress passed the Platt Amendment, which stipulated conditions for U.S. withdrawal from the island; the conditions allowed for a strong American role despite the promise of withdrawal.[109]

Cuba gained independence in 1902[110] but became a de facto protectorate of the United States.[111] Roosevelt won congressional approval for a reciprocity agreement with Cuba in December 1902, thereby lowering tariffs on trade between the two countries.[112] In 1906, an insurrection erupted against Cuban President Tomás Estrada Palma due to the latter's alleged electoral fraud. Both Estrada Palma and his liberal opponents called for an intervention by the U.S., but Roosevelt was reluctant to intervene.[113] When Estrada Palma and his Cabinet resigned, Secretary of War Taft declared that the U.S. would intervene under the terms of the Platt Amendment, beginning the Second Occupation of Cuba.[114] U.S. forces restored peace to the island, and the occupation ceased shortly before the end of Roosevelt's presidency.[115]

Puerto Rico

After Puerto Rico was devastated by the massive 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane, Secretary of War Root proposed to eliminate all tariff barriers with Puerto Rico. His proposal initiated a serious disagreement between the McKinley administration and Republican leaders in Congress, who were wary of lowering the tariffs on the newly acquired territories. Rather than relying on Democratic votes to pass a no-tariff bill, McKinley compromised with Republican leaders on a bill that cut tariffs on Puerto Rican goods to a fraction of the rates set by the Dingley Tariff. While considering the tariff bill, the Senate also began hearings on a bill to establish a civil government for Puerto Rico, which the Senate passed in a party-line vote. McKinley signed the Foraker Act into law on April 12, 1900. Under the terms of the bill, all revenue collected from the tariff on Puerto Rican goods would be used for Puerto Rico, and the tariff would cease to function once the government of Puerto Rico established its own taxation system.[116] In the 1901 Insular Cases, the Supreme Court upheld the McKinley administration's policies in the territories acquired in the Spanish–American War, including the establishment of Puerto Rico's government.[117]

Though it had largely been an afterthought in the Spanish–American War, Puerto Rico became an important strategic asset for the U.S. due to its position in the Caribbean Sea. The island provided an ideal naval base for defense of the Panama Canal, and it also served as an economic and political link to the rest of Latin America. Prevailing racist attitudes made Puerto Rican statehood unlikely, so the U.S. carved out a new political status for the island. The Foraker Act and subsequent Supreme Court cases established Puerto Rico as the first unincorporated territory, meaning that the United States Constitution would not fully apply to Puerto Rico. Though the U.S. imposed tariffs on most Puerto Rican imports, it also invested in the island's infrastructure and education system. Nationalist sentiment remained strong on the island and Puerto Ricans continued to primarily speak Spanish rather than English.[118]

Roosevelt as president

Victory in the war made the United States a power in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. McKinley ran on his foreign policy achievement and scored a landslide in the 1900 election. His opponent William Jennings Bryan attacked imperialism, although he had been a leader in demanding war in 1898.[119] After McKinley's assassination in 1901, Roosevelt promised to continue his policies and increase American influence in world affairs.[120] Reflecting this view, Roosevelt stated in 1905, "We have become a great nation, forced by the face of its greatness into relations with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people with such responsibilities." Roosevelt believed that the United States had a duty to uphold a balance of power in international relations and seek to reduce tensions among the great powers.[121] He was also adamant in upholding the Monroe Doctrine, the American policy of opposing European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere.[122] Roosevelt viewed the German Empire as the biggest potential threat to the United States, and he feared that the Germans would attempt to establish a base in the Caribbean Sea. Given this fear, Roosevelt pursued closer relations with Britain, a rival of Germany, and responded skeptically to German Kaiser Wilhelm II's efforts to curry favor with the United States.[123] Roosevelt also attempted to expand U.S. influence in East Asia and the Pacific, where the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire exercised considerable authority.[124]

Roosevelt placed an emphasis on expanding and reforming the United States military.[125] The United States Army, with 39,000 men in 1890, was the smallest and least powerful army of any major power in the late 19th century. By contrast, France's army consisted of 542,000 soldiers.[126] The Spanish–American War had been fought mostly by temporary volunteers and state national guard units, and it demonstrated that more effective control over the department and bureaus was necessary.[127] Roosevelt gave strong support to the reforms proposed by Secretary of War Elihu Root, who wanted a uniformed chief of staff as general manager and a European-style general staff for planning. Overcoming opposition from General Nelson A. Miles, the Commanding General of the United States Army, Root succeeded in enlarging West Point and establishing the U.S. Army War College as well as the general staff. Root also changed the procedures for promotions, organized schools for the special branches of the service, devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line,[128] and increased the Army's connections to the National Guard.[129]

Upon taking office, Roosevelt made naval expansion a priority, and his tenure saw an increase in the number of ships, officers, and enlisted men in the Navy.[129] With the publication of The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 in 1890, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan had been immediately hailed as an outstanding naval theorist by the leaders of Europe. Roosevelt paid very close attention to Mahan's emphasis that only a nation with a powerful fleet could dominate the world's oceans, exert its diplomacy to the fullest, and defend its own borders.[130][131] By 1904, the United States had the fifth largest navy in the world, and by 1907, it had the third largest. Roosevelt sent what he dubbed the "Great White Fleet" around the globe in 1908–1909 to make sure all the naval powers understood the United States was now a major player. Though Roosevelt's fleet did not match the overall strength of the British fleet, it became the dominant naval force in the Western Hemisphere.[132][133][134]

In summarizing Roosevelt's foreign policy, William Harbaugh argues:

- Roosevelt’s legacy is judicious support of the national interest and promotion of world stability through the maintenance of a balance of power; creation or strengthening of international agencies, and resort to their use when practicable; and implicit resolve to use military force, if feasible, to foster legitimate American interests.[135]

Rapprochement with Great Britain

The Great Rapprochement began with American support for Britain in the Boer War and British support of the United States during the Spanish–American War. It continued as Britain withdrew its fleet from the Caribbean in favor of focusing on the rising German naval threat.[136][137] Roosevelt sought a continuation of close relations with Britain in order to ensure peaceful, shared hegemony over the Western hemisphere. With the British acceptance of the Monroe Doctrine and American acceptance of the British control of Canada, only two potential major issues remained between the U.S. and Britain: the Alaska boundary dispute and construction of a canal across Central America. Under McKinley, Secretary of State Hay had negotiated the Hay–Pauncefote Treaty, in which the British consented to U.S. construction of the canal. Roosevelt won Senate ratification of the treaty in December 1901.[138]

The boundary between Alaska and Canada had become an issue in the late 1890s due to the Klondike Gold Rush, as American and Canadian prospectors in Yukon and Alaska raced to make for gold claims. Access to the main Canadian gold fields required a transit of Alaska. Canada wanted an all-Canadian route. They rejected McKinley's offer to lease them a port and demanded full ownership according to their maps. A treaty on the border between Alaska and Canada had been reached by Britain and Russia in the 1825 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, and the United States had assumed Russian claims through the 1867 Alaska Purchase. Washington argued that the treaty had given Alaska sovereignty over disputed coastline. [139] Meanwhile, the Venezuela Crisis briefly threatened interrupted negotiations over the border, but conciliatory actions by London ended the crisis and reduced the risk of hostilities regarding Alaska. In January 1903, the U.S. and Britain reached the Hay–Herbert Treaty, which would empower a six-member tribunal, composed of American, British, and Canadian delegates, to set the border. With the help of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Roosevelt won the Senate's consent to the Hay–Herbert Treaty in February 1903.[140] The tribunal consisted of three American delegates, two Canadian delegates, and Lord Alverstone, the lone delegate from Britain itself. Alverstone joined with the three American delegates in accepting most American claims, and the tribunal announced its decision in October 1903. The outcome of the tribunal strengthened relations between the United States and Britain, though many Canadians were outraged by the British betrayal of the Canadian interest.[141]

Venezuela Crisis and Roosevelt Corollary

In December 1902, an Anglo-German blockade of Venezuela began an incident known as the Venezuelan Crisis. The blockade originated due to money owed by Venezuela to European creditors. Both powers assured the U.S. that they were not interested in conquering Venezuela, and Roosevelt sympathized with the European creditors, but he became suspicious that Germany would demand territorial indemnification from Venezuela. Roosevelt and Hay feared that even an allegedly temporary occupation could lead to a permanent German military presence in the Western Hemisphere.[123] As the blockade began, Roosevelt mobilized the U.S. fleet under the command of Admiral George Dewey.[142] Roosevelt threatened to destroy the German fleet unless the Germans agreed to arbitration regarding the Venezuelan debt, and Germany chose arbitration rather than war.[143] Through American arbitration, Venezuela reached a settlement with Germany and Britain in February 1903.[144]

Though Roosevelt would not tolerate European territorial ambitions in Latin America, he also believed that Latin American countries should pay the debts they owed to European credits.[145] In late 1904, Roosevelt announced his Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. It stated that the U.S. would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they defaulted on their debts to European creditors and, in effect, guarantee their debts, making it unnecessary for European powers to intervene to collect unpaid debts. Roosevelt's pronouncement was especially meant as a warning to Germany, and had the result of promoting peace in the region, as the Germans decided to not intervene directly in Venezuela and in other countries.[146]

A crisis in the Dominican Republic became the first test case for the Roosevelt Corollary. Deeply in debt, the nation struggled to repay its European creditors. Fearing another intervention by Germany and Britain, Roosevelt reached an agreement with Dominican President Carlos Felipe Morales to take temporary control of the Dominican economy, much as the U.S. had done on a permanent basis in Puerto Rico. The U.S. took control of the Dominican customs house, brought in economists such as Jacob Hollander to restructure the economy, and ensured a steady flow of revenue to the Dominican Republic's foreign creditors. The intervention stabilized the political and economic situation in the Dominican Republic, and the U.S. role on the island would serve as a model for Taft's dollar diplomacy in the years after Roosevelt left office.[147]

Panama Canal

Under McKinley, Secretary of State Hay engaged in negotiations with Britain over the possible construction of a canal across Central America. The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, which the two nations had signed in 1850, prohibited either from establishing exclusive control over a canal there. The Spanish–American War had exposed the difficulty of maintaining a two-ocean navy without a connection closer than Cape Horn, at the southern tip of South America.[148] With American business, humanitarian and military interests even more involved in Asia following the Spanish–American War, a canal seemed more essential than ever, and McKinley pressed for a renegotiation of the treaty.[148] The British, who were distracted by the ongoing Second Boer War, agreed to negotiate a new treaty.[149] Hay and the British ambassador, Julian Pauncefote, agreed that the United States could control a future canal, provided that it was open to all shipping and not fortified. McKinley was satisfied with the terms, but the Senate rejected them, demanding that the United States be allowed to fortify the canal. Hay was embarrassed by the rebuff and offered his resignation, but McKinley refused it and ordered him to continue negotiations to achieve the Senate's demands. He was successful, and a new treaty was drafted and approved, but not before McKinley's assassination in 1901.[150]

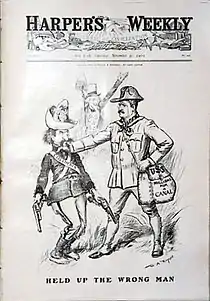

Roosevelt sought the creation of a canal through Central America which would link the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Most members of Congress preferred that the canal cross through Nicaragua, which was eager to reach an agreement, but Roosevelt preferred the isthmus of Panama, under the loose control of Colombia. Colombia had been engulfed in a civil war since 1898, and a previous attempt to build a canal across Panama had failed under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps. A presidential commission appointed by McKinley had recommended the construction of the canal across Nicaragua, but it noted that a canal across Panama could prove less expensive and might be completed more quickly.[151] Roosevelt and most of his advisers favored the Panama Canal, as they believed that war with a European power, possibly Germany, could soon break out over the Monroe Doctrine and the U.S. fleet would remain divided between the two oceans until the canal was completed.[152] After a long debate, Congress passed the Spooner Act of 1902, which granted Roosevelt $170 million to build the Panama Canal.[153] Following the passage of the Spooner Act, the Roosevelt administration began negotiations with the Colombian government regarding the construction of a canal through Panama.[152]

The U.S. and Colombia signed the Hay–Herrán Treaty in January 1903, granting the U.S. a lease across the isthmus of Panama.[152] The Colombian Senate refused to ratify the treaty, and attached amendments calling for more money from the U.S. and greater Colombian control over the canal zone.[154] Panamanian rebel leaders, long eager to break off from Colombia, appealed to the United States for military aid.[155] Roosevelt saw the leader of Columbia, José Manuel Marroquín, as a corrupt and irresponsible autocrat, and he believed that the Colombians had acted in bad faith by reaching and then rejecting the treaty.[156] After an insurrection broke out in Panama, Roosevelt dispatched the USS Nashville to prevent the Colombian government from landing soldiers in Panama, and Colombia was unable to re-establish control over the province.[157] Shortly after Panama declared its independence in November 1903, the U.S. recognized Panama as an independent nation and began negotiations regarding construction of the canal. According to Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris, most other Latin American nations welcomed the prospect of the new canal in hopes of increased economic activity, but anti-imperialists in the U.S. raged against Roosevelt's aid to the Panamanian separatists.[158]

Secretary of State Hay and French diplomat Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, who represented the Panamanian government, quickly negotiated the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. Signed on November 18, 1903, it established the Panama Canal Zone—over which the United States would exercise sovereignty—and insured the construction of an Atlantic to Pacific ship canal across the Isthmus of Panama. Panama sold the Canal Zone (consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending five miles (8.0 km) on each side of the centerline) to the United States for $10 million and a steadily increasing yearly sum.[159] In February 1904, Roosevelt won Senate ratification of the treaty in a 66-to-14 vote.[160] The Isthmian Canal Commission, supervised by Secretary of War Taft, was established to govern the zone and oversee the construction of the canal.[161] Roosevelt appointed George Whitefield Davis as the first governor of the Panama Canal Zone and John Findley Wallace as the Chief Engineer of the canal project.[162] When Wallace resigned in 1905, Roosevelt appointed John Frank Stevens, who built a railroad in the canal zone and initiated the construction of a lock canal.[163] Stevens was replaced in 1907 by George Washington Goethals, who saw construction through to its completion.[164] Roosevelt traveled to Panama in November 1906 to inspect progress on the canal,[165] becoming the first sitting president to travel outside of the United States.[166]

Treaties among Panama, Colombia, and the United States to resolve disputes arising from the Panamanian Revolution of 1903 were signed by the Roosevelt administration in early 1909, and were approved by the Senate and also ratified by Panama. Colombia, however, declined to ratify the treaties, and after the 1912 elections, Knox offered $10 million to the Colombians (later raised to $25 million). The Colombians felt the amount inadequate, and the matter was not settled under the Taft administration.[167] The canal was completed in 1914.

Arbitration and mediation

A major turning point in establishing America's role in European affairs was the Moroccan crisis of 1905–1906. France and Britain had agreed that France would dominate Morocco, but Germany suddenly protested aggressively, with the disregard for quiet diplomacy characteristic of Kaiser Wilhelm. Berlin asked Roosevelt to serve as an intermediary, and he helped arrange a multinational conference at Algeciras, Morocco, where the crisis was resolved. Roosevelt advised Europeans in the future the United States would probably avoid any involvement in Europe, even as a mediator, so European foreign ministers stopped including the United States as a potential factor in the European balance of power.[168][169]

Russo-Japanese War

Russia had occupied the Chinese region of Manchuria in the aftermath of the 1900 Boxer Rebellion, and the United States, Japan, and Britain all sought the end of its military presence in the region. Russia agreed to withdrawal its forces in 1902, but it reneged on this promise and sought to expand its influence in Manchuria to the detriment of the other powers.[170] Roosevelt was unwilling to consider using the military to intervene in the far-flung region, but Japan prepared for war against Russia in order to remove it from Manchuria.[171] When the Russo-Japanese War broke out in February 1904, Roosevelt sympathized with the Japanese but sought to act as a mediator in the conflict. He hoped to uphold the Open Door policy in China and prevent either country from emerging as the dominant power in East Asia.[172] Throughout 1904, both Japan and Russia expected to win the war, but the Japanese gained a decisive advantage after capturing the Russian naval base at Port Arthur in January 1905.[173] In mid-1905, Roosevelt persuaded the parties to meet in a peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, starting on August 5. His persistent and effective mediation led to the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth on September 5, ending the war. For his efforts, Roosevelt was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize.[174] The Treaty of Portsmouth resulted in the removal of Russian troops from Manchuria, and it gave Japan control of Korea and the southern half of Sakhalin Island.[175]

Algeciras Conference

In 1906, at the request of Kaiser Wilhelm II, Roosevelt convinced France to attend the Algeciras Conference as part of an effort to resolve the First Moroccan Crisis. After signing the Entente Cordiale with Britain, France had sought to assert its dominance over Morocco, and a crisis had begun after Germany protested this move. By asking Roosevelt to convene an international conference on Morocco, Kaiser Wilhelm II sought to test the new Anglo-British alliance, check French expansion, and potentially draw the United States into an alliance against France and Britain.[176] Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon protested U.S. involvement in European affairs, but Secretary of State Root and administration allies like Senator Lodge helped defeat Bacon's resolution condemning U.S. participation in the Algeciras Conference.[177] The conference was held in the city of Algeciras, Spain, and 13 nations attended. The key issue was control of the police forces in the Moroccan cities, and Germany, with a weak diplomatic delegation, found itself in a decided minority. Hoping to avoid an expansion of German power in North Africa, Roosevelt secretly supported France, and he cooperated closely with the French ambassador. An agreement among the powers, reached on April 7, 1906, slightly reduced French influence by reaffirming the independence of the Sultan of Morocco and the economic independence and freedom of operations of all European powers within the country. Germany gained nothing of importance but was mollified and stopped threatening war.[178]

Taft's policies

Taft was opposed to the traditional practice of rewarding wealthy supporters with key ambassadorial posts, preferring that diplomats not live in a lavish lifestyle and selecting men who, as Taft put it, would recognize an American when they saw one. High on his list for dismissal was the ambassador to France, Henry White, whom Taft knew and disliked from his visits to Europe. White's ousting caused other career State Department employees to fear that their jobs might be lost to politics. Taft also wanted to replace the Roosevelt-appointed ambassador in London, Whitelaw Reid, but Reid, owner of the New-York Tribune, had backed Taft during the campaign, and both William and Nellie Taft enjoyed his gossipy reports. Reid remained in place until his 1912 death.[179]

Taft was the leader in settling international disputes by arbitration. In 1911 Taft and his Secretary of State, Philander C. Knox negotiated major treaties with Great Britain and with France providing that differences be arbitrated. Disputes had to be submitted to the Hague Court or other tribunal. These were signed in August 1911 but had to be ratified by a two thirds vote of the Senate . Neither Taft nor Knox consulted with members of the Senate during the negotiating process. By then many Republicans were opposed to Taft, and the president felt that lobbying too hard for the treaties might cause their defeat. He made some speeches supporting the treaties in October, but the Senate added amendments Taft could not accept, killing the agreements.[180]

The arbitration issue opens a window on a bitter dispute among progressives. Many progressives looked to legal arbitration as an alternative to warfare. Taft was a constitutional lawyer who later became Chief Justice; he had a deep understanding of the legal issues.[181] Taft's political base was the conservative business community which largely supported peace movements before 1914—his mistake in this case was a failure to mobilize that base. The businessmen believed that economic rivalries were cause of war, and that extensive trade led to an interdependent world that would make war a very expensive and useless anachronism. One early success came in the Newfoundland fisheries dispute between the United States and Britain in 1910. Taft's 1911 treaties with France and Britain were killed by Roosevelt, who had broken with his protégé in 1910. They were dueling for control of the Republican Party. Roosevelt worked with his close friend Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to impose those amendments that ruined the goals of the treaties. Lodge thought the treaties impinge too much on senatorial prerogatives.[182] Roosevelt, however, was acting to sabotage Taft's campaign promises.[183] At a deeper level, Roosevelt truly believed that arbitration was a naïve solution and that great issues had to be decided by warfare. The Rooseveltian approach had a near-mystical faith in the ennobling nature of war. It endorsed jingoistic nationalism as opposed to the businessmen's calculation of profit and national interest.[184]

Although no general arbitration treaty was entered into, Taft's administration settled several disputes with Great Britain by peaceful means, often involving arbitration. These included a settlement of the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick, a long-running dispute over seal hunting in the Bering Sea that also involved Japan, and a similar disagreement regarding fishing off Newfoundland.[185]

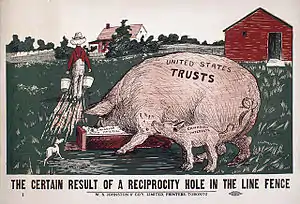

Canada rejects reciprocal trade treaty

Anti-Americanism reached a shrill peak in 1911 in Canada.[186] Taft hoped to regain momentum with a reciprocity treaty with Canada that represented a step toward free trade of the sort that had prevailed 1854–1866. The Liberal government in Ottawa under Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier happily negotiated a Reciprocity treaty that would lower tariffs and remove many trade barriers. Canadian manufacturing interests were alarmed that free trade would allow the bigger and more efficient American factories to take their Canadian markets. Conservatives in Canada opposed an accord, fearing more Americanization would result as Canada reoriented away from Britain, which was losing economic status, and be pulled toward the huge economy to the South. Quebec Catholics were warned the Church would be disestablished if Canada became part of the United States.

American farm and fisheries interests, and paper mills, objected because they would lose tariff protection. Nonetheless, Taft reached an agreement with Canadian officials in early 1911, and Congress approved it in late July, 1911. However, the Canadian Parliament deadlocked over the issue, and Canada called the 1911 election. It turned on economic and fears and especially on Canadian nationalism. Fear of potential loss outweighed hoped for gains as the Conservatives made it a central issue, warning that it would be a "sell out" to the United States with economic annexation a grave threat.[187] The Conservative slogan was "No truck or trade with the Yankees", as they appealed to Canadian nationalism and nostalgia for the British Empire to win a major victory.[188] The treaty was dead and this unexpected loss for Taft further hurt his reputation. [189][190]

Dollar Diplomacy

Taft and Secretary of State Knox instituted a policy of Dollar Diplomacy towards Latin America, believing U.S. investment would benefit all involved and minimize European influence in the area. Although exports rose sharply during Taft's administration, his Dollar Diplomacy policy was unpopular among Latin American states that did not wish to become financial protectorates of the United States. Dollar Diplomacy also faced opposition in the U.S. Senate, as many senators believed the U.S. should not interfere abroad.[191]

In Nicaragua, American diplomats quietly favored rebel forces under Juan J. Estrada against the government of President José Santos Zelaya, who wanted to revoke commercial concessions granted to American companies.[192] Secretary Knox was reportedly a major stockholder in one of the companies that would be hurt by such a move.[193] The country was in debt to several foreign powers, and the U.S. was unwilling to have it (along with its alternate canal route) fall into the hands of Europeans. Zelaya and his elected successor, José Madriz, were unable to put down the rebellion, and in August 1910, Estrada's forces took the capital of Managua. The U.S. had Nicaragua accept a loan, and sent officials to ensure it was repaid from government revenues. The country remained unstable, and after another coup in 1911 and more disturbances in 1912, Taft sent troops; though most were soon withdrawn, some remained as late as 1933.[194][195]

Mexican Revolution

No foreign affairs controversy tested Taft's statesmanship and commitment to peace more than the collapse of the Mexican regime and subsequent turmoil of the Mexican Revolution.[196] When Taft entered office, Mexico was increasingly restless under the longtime dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. Díaz faced strong political opposition from Francisco Madero, who was backed by a sizeable proportion of the population,[197] and was also confronted with serious social unrest sparked by Emiliano Zapata in the south and by Pancho Villa in the north. In October 1909, Taft and Díaz exchanged visits across the Mexico–United States border, at El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Their meetings were the first ever between a U.S. and a Mexican president, and also represented the first time an American president visited Mexico.[198][199] Diaz hoped to use the meeting as a propaganda tool to show that his government had the U.S.'s unconditional support. For his part, Taft was mainly interested in protecting American corporate investments in Mexico.[198] The symbolically important meetings helped pave the way for the start of construction on the Elephant Butte Dam project in 1911.[198]

The situation in Mexico deteriorated throughout 1910, and there were a number of incidents in which Mexican rebels crossed the U.S. border to obtain horses and weapons. After Díaz jailed opposition candidate Madero prior to the 1910 presidential election, Madero's supporters responded by taking up arms against the government. This unrest resulted in both the ousting of Díaz and a revolution that would continue for another ten years. In the Arizona Territory, two citizens were killed and almost a dozen injured, some as a result of gunfire across the border. Taft would not be goaded into fighting and so instructed the territorial governor not to respond to provocations.[196] In March 1911, he sent 20,000 American troops up to the Mexican border to protect American citizens and financial investments in Mexico. He told his military aide, Archibald Butt, that "I am going to sit on the lid and it will take a great deal to pry me off".[200]

Relations with Japan, 1897–1913

Roosevelt saw Japan as the rising power in Asia, in terms of military strength and economic modernization. He viewed Korea as a backward nation and did not object to Japan's attempt to gain control over Korea. With the withdrawal of the American legation from Seoul and the refusal of the Secretary of State to receive a Korean protest mission, the Americans signaled they would not intervene militarily to stop Japan's planned takeover of Korea.[201] In mid-1905, Taft and Japanese Prime Minister Katsura Tarō jointly produced the Taft–Katsura agreement. The discussion clarified exactly what position each nation took. Japan stated that it had no interest in the Philippines, while the U.S. stated that it considered Korea to be part of the Japanese sphere of influence.[202][203]

Vituperative anti-Japanese sentiment among Americans on the West Coast, soured relations during the latter half of Roosevelt's term.[204] In 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education caused a diplomatic incident by ordering the segregation of all schoolchildren in the city.[205] The Roosevelt administration did not want to anger Japan by passing legislation to bar Japanese immigration to the U.S., as had previously been done for Chinese immigration. Instead the two countries, led by Secretary Root and Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi Tadasu, reached the informal Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907. Japan agreed to stop the emigration of unskilled Japanese laborers to the U.S. and Hawaii. The segregation order of the San Francisco School Board was cancelled. The agreement remained in effect until the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, in which Congress forbade all immigration from Japan.[206][207] Despite the agreement, tensions with Japan would continue to simmer due to the mistreatment of Japanese immigrants by local governments. Roosevelt never feared war with the Japanese during his tenure, but the friction with Japan encouraged further naval build-up and an increased focus on the security of the American position in the Pacific.[208]

Taft continued Roosevelt's policies regarding immigration from China and Japan. A revised treaty of friendship and navigation entered into by the U.S. and Japan in 1911 granted broad reciprocal rights to Japanese in America and Americans in Japan, but were premised on the continuation of the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907. There was objection on the West Coast when the treaty was submitted to the Senate, but Taft informed politicians that there was no change in immigration policy.[209]

Relations with China, 1897–1913

Secretary of State John Hay had charge of China policy until 1904, when war broke out between Russia and Japan and Roosevelt himself took over. Both of them started with grand ambitions about new American involvements in the region, but each, within a year or so, pulled back realizing that American public opinion did not want deeper involvement in Asia. So their efforts to find a naval port, or to build railroads, or increased trade, came to naught.[210]

Even before peace negotiations began with Spain, Hay had the president ask Congress to set up a commission to examine trade opportunities in Asia and espoused an "Open Door Policy", in which all nations would freely trade with China and none would seek to violate that nation's territorial integrity.Hay circulated two notes promoting the Open Door to the European powers. Great Britain favored the idea, but Russia opposed it; France, Germany, Italy and Japan told Hay they agreed in principle, but only if all the other nations went along. Hay then announced that the principal had been adopted by consensus, and indeed every power promised to uphold the Open Door, and objected loudly when Russia or Japan tried to flout it.[211][212]

Boxer rebellion 1900

American missionaries were threatened and trade with China became imperiled as the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 menaced foreigners and their property in China.[213] Americans and other westerners in Peking were besieged and, in cooperation with seven other powers, McKinley ordered 5000 troops to the city in June 1900 in the China Relief Expedition.[214] The rescue went well, but several Congressional Democrats objected to McKinley dispatching troops without consulting Congress.[215] McKinley's actions set a precedent that led to most of his successors exerting similar independent control over the military.[214] After the rebellion ended, the United States reaffirmed its commitment to the Open Door policy, which became the basis of American policy toward China.[216] It used the cash reparations paid by China to bring Chinese students to Americans schools.[217]

1905 Chinese boycott

In response to severe restrictions on Chinese immigration to the United States, the overseas Chinese living in the United States organized a boycott whereby people in China refuse to purchase American products. The project was organized by a reform organization based in the United States, Baohuang Hui. Unlike the reactionary Boxers, these reformers were modernizers. The Manchu government had supported the Boxers, but these reformers—of whom Sun Yat-sen was representative, opposed the government. The boycott was put into effect by merchants and students in south and central China. It made only a small economic impact, because China bought few American products apart from Standard Oil's kerosene. Washington was outraged and treated the boycott as a Boxer-like violent attack, and demanded the Peking government stop it or else. President Theodore Roosevelt asked Congress for special funding for a naval expedition. Washington refused to consider softening the exclusion laws because it responded to deep-seated anti-Chinese prejudices that were widespread especially on the West Coast. It now began to denounce Chinese nationalism.[218] The impact on the Chinese people, in China and abroad, was far-reaching. Jane Larson argues the boycott, "marked the beginning of mass politics and modern nationalism in China. Never before had shared nationalistic aspirations mobilized Chinese across the world in political action, joining the cause of Chinese migrants with the fate of the Chinese nation."[219][220][221]

President Taft

Having served as the governor of the Philippines, Taft was keenly interested in Asian-Pacific affairs.[222] Because of the potential for trade and investment, Taft ranked the post of minister to China as most important in the Foreign Service. Knox did not agree, and declined a suggestion that he go to China to view the facts on the ground. American exports to China had declined sharply from $58 million in 1905 to only $16 million in 1910.[223] Taft replaced Roosevelt's minister William W. Rockhill because he neglected trade issues, and named William J. Calhoun. Knox did not listen to Calhoun on policy, and there were often conflicts.[224] Taft and Knox tried unsuccessfully to extend John Hay's Open Door Policy to Manchuria.[225] In 1909, a British-led consortium began negotiations to finance the "Hukuang Loan" to finance a railroad from Hankow to Szechuan.[226] Taft for years sought American participation in this project but first Britain then China blocked his efforts. Finally the western powers in 1911 forced China to approve the project. Widespread opposition across China, especially in the Chinese army, to the western imperialism represented by the Hukuang Loan was a major spark that incited the Chinese Revolution of 1911 .[227][228]

Revolution 1911

After the Chinese Revolution broke out in 1911, the revolt's leaders chose Sun Yat Sen as provisional president of what became the Republic of China, overthrowing the Manchu Dynasty. Taft was reluctant to recognize the new government, although American public opinion was in favor of it. The U.S. House of Representatives in February 1912 passed a resolution supporting a Chinese republic, but Taft and Knox felt recognition should come as a concerted action by Western powers. In his final annual message to Congress in December 1912, Taft indicated that he was moving towards recognition once the republic was fully established, but by then he had been defeated for re-election and he did not follow through.[229]

See also

- East Asia–United States relations

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Entente Cordiale 1904, Britain and France

- First Moroccan Crisis March 1905–May 1906

- Second Moroccan Crisis 1911

- Causes of World War I

References

- Gould, pp. 17–18.

- Morgan, pp. 194–95, 285; Leech, pp. 152–53.

- Gould, pp. 94, 129.

- Gould, p. 14.

- Morgan, pp. 199–200.

- Gould, pp. 16–17, 102, 174–76.

- Gould 2011, pp. 10–12.

- Morris (2001) pp 9-10

- Morris (2001) pp 22-23

- Ralph Eldin Minger, William Howard Taft and United States Foreign Policy: The Apprenticeship Years, 1900-1908 (1975).

- Morris (2001) pp. 394-395

- Anderson 1973, p. 37.

- Coletta 1973, p. 45.

- Coletta 1973, pp. 49–50.

- Gould, Taft p 81.

- Pringle, Taft 1:384-85.

- Anderson 1973, p. 71.

- Scholes and Scholes, p. 25.

- Coletta 1973, pp. 183–185.

- Mary Thornton, "U.S. Backs China's Move to Reopen 1911 Railroad Bond Case" Washington Post August 19, 1983.

- Walter Vinton Scholes and Marie V.Scholes, The Foreign Policies of the Taft Administration (1970) pp 247-248.

- John Martin Carroll; George C. Herring (1996). Modern American Diplomacy. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9780842025553.

- Sprout, Harold Hance; Sprout, Margaret (8 December 2015). Rise of American Naval Power. Princeton University Press. pp. 286–288.

- Herring, pp. 296–297.

- Herring, pp. 305–306.

- Alyn Brodsky (2000). Grover Cleveland: A Study in Character. Macmillan. p. 1.

- Gould, pp. 49–50.

- Gould, pp. 48–50.

- Osborne, pp. 285–297.

- Osborne, pp. 299–301.

- Morgan, p. 225.

- Thomas J. Osborne, "The Main Reason for Hawaiian Annexation in July, 1898," Oregon Historical Quarterly (1970) 71#2 pp. 161–178 in JSTOR

- Bailey, Thomas A. (1937). "Was the Presidential Election of 1900 a Mandate on Imperialism?". Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 24 (1): 43–52. doi:10.2307/1891336. JSTOR 1891336.

- Henry F. Graff (2002). Grover Cleveland: The American Presidents Series: The 22nd and 24th President, 1885–1889 and 1893–1897. p. 121. ISBN 9780805069235.

- Fred H. Harrington, "The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898–1900." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 22#2 (1935): 211–230. online

- Fred Harvey Harrington, "Literary Aspects of American Anti-Imperialism 1898–1902," New England Quarterly, 10#4 (1937), pp 650–67. online.

- Robert L. Beisner, Twelve Against Empire: The Anti-Imperialists, 1898–1900 (1968).

- Warren Zimmermann, "Jingoes, Goo-Goos, and the Rise of America's Empire." The Wilson Quarterly (1976) 22#2 (1998): 42–65. Online

- William Michael Morgan, Pacific Gibraltar: U.S.-Japanese Rivalry Over the Annexation of Hawaii, 1885–1898 (2011) pp 200–1; see online review.

- Herring, pp. 317–318.

- Gould, pp. 98–99.

- Morgan, p. 223.

- Robert L. Beisner, ed. (2003). American Foreign Relations Since 1600: A Guide to the Literature. ABC-CLIO. p. 414. ISBN 9781576070802.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Offner, pp. 51–52.

- Gould, p. 61.

- George W. Auxier, "The propaganda activities of the Cuban Junta in precipitating the Spanish–American War, 1895–1898." Hispanic American Historical Review 19.3 (1939): 286–305 in JSTOR.

- Gould, pp. 64–65.

- Gould, pp. 65–66.

- Gould, pp. 68–70.

- Julius W. Pratt, "American business and the Spanish–American War." Hispanic American Historical Review 14#2 (1934): 163–201. in JSTOR, quote on p. 168.

- Bloodworth, pp. 135–157.

- Donald H. Dyal et al. eds. (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War. p. 114. ISBN 9780313288524.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gould, p. 71–74.

- Leech, pp. 171–72.

- Leech, p. 173; Gould, pp. 78–79.

- Gould, pp. 79–81.

- Gould, pp. 86–87.

- Sylvia L. Hilton and Steve Ickringill, European Perceptions of the Spanish–American War of 1898 (Peter Lang, 1999).

- Offner, p. 58–59.

- See William McKinley “First Annual Message” December 6, 1897.

- Louis A. Perez, Jr., review, in Journal of American History (Dec. 2006), p 889. See more detail in Perez, The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography (1998) pp 23–56.

- Perez (1998) pp 46–47.

- Robert Endicott Osgood, Ideals and self-interest in America's foreign relations: The great transformation of the twentieth century (1953) p 43.

- Joseph A. Fry, "William McKinley and the coming of the Spanish–American War: A study of the besmirching and redemption of an historical image." Diplomatic History 3#1 (1979): 77–98.

- Robert L. Beisner, From the Old Diplomacy to the New, 1865–1900 (New York, 1975), p. 114

- Nick Kapur, "William McKinley's Values and the Origins of the Spanish‐American War: A Reinterpretation." Presidential Studies Quarterly 41.1 (2011): 18-38 online.

- Joseph A. Fry, "William McKinley and the Coming of the Spanish–American War: A Study of the Besmirching and Redemption of an Historical Image" Diplomatic History (1979) 3#1 p 96

- Gould, pp. 91–93.

- Gould, pp. 102–03.

- Gould, pp. 103–105.

- David W BUght, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001), pp. 350–54.

- Robert J. Norrell, Up from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington (2009) pp. 164, 168–69, 289.

- Gould, pp. 94–96.

- David P. Barrows, "The Governor-General of the Philippines Under Spain and the United States." American Historical Review 21.2 (1916): 288–311. online

- Paolo E. Coletta, "McKinley, the Peace Negotiations, and the Acquisition of the Philippines." Pacific Historical Review 30.4 (1961): 341–50.

- Gould, pp. 104–106.

- Gould, pp. 106–108.