Foreign policy of the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration

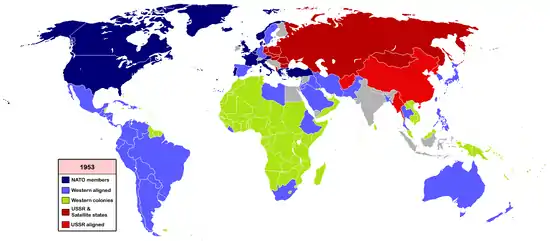

The foreign policy of Dwight D. Eisenhower administration was the foreign policy of the United States from 1953 to 1961, when Dwight D. Eisenhower served as the President of the United States. Eisenhower held office during the Cold War, a period of sustained geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

World War II

President of the United States

First Term

Second Term

Post-Presidency

|

||

The Eisenhower administration continued the Truman administration's policy of containment, which called for the United States to prevent the spread of Communism to new states. Eisenhower's New Look defense policy stressed the importance of nuclear weapons as a deterrent to military threats, and the United States built up a stockpile of nuclear weapons and nuclear delivery systems during Eisenhower's presidency. A major uprising broke out in Hungary in 1956; the Eisenhower administration did not become directly involved, but condemned the Soviet military response. As part of a move towards détente, Eisenhower sought to reach a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, but the 1960 U-2 incident derailed a Cold War summit in Paris.

Soon after taking office, Eisenhower negotiated an end to the Korean War, resulting in the partition of Korea. The following year, he played a major role in the defeat of the Bricker Amendment, which would have limited the president's treaty making power and ability to enter into executive agreements with foreign nations. The Eisenhower administration used propaganda and covert action extensively, and the Central Intelligence Agency instigated or took part in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état and the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état. The Eisenhower administration played a role in the partition of Vietnam at the 1954 Geneva Conference, and the U.S. subsequently directed aid to the newly-formed country of South Vietnam. The Eisenhower administration also established the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization as an alliance of anti-Communist states in Southeast Asia, and resolved two crises with China over Taiwan.

In 1956, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, sparking the Suez Crisis, in which a coalition of France, Britain, and Israel took control of the canal. Concerned about the economic and political impacts of the invasion, Eisenhower pressured Britain and France to withdraw. In the aftermath of the crisis, Eisenhower announced the Eisenhower Doctrine, under which any country in the Middle East could request American economic assistance or aid from U.S. military forces. The Cuban Revolution broke out during Eisenhower's second term, resulting in the replacement of pro-U.S. President Fulgencio Batista with Fidel Castro. In response to the revolution, the Eisenhower administration broke ties with Cuba and began preparations for an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles, ultimately resulting in the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion after Eisenhower left office.

Cold War

Eisenhower's 1952 candidacy was motivated in large part by his opposition to Taft's isolationist views; he did not share Taft's concerns regarding U.S. involvement in collective security and international trade, the latter of which was embodied by the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.[1] The Cold War dominated international politics in the 1950s. As both the United States and the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons, any conflict presented the risk of escalation into nuclear warfare.[2] Eisenhower continued the basic Truman administration policy of containment of Soviet expansion and the strengthening of the economies of Western Europe. Eisenhower's overall Cold War policy was described by NSC 174, which held that the rollback of Soviet influence was a long-term goal, but that the United States would not provoke war with the Soviet Union.[3] He planned for the full mobilization of the country to counter Soviet power, and emphasized making a "public effort to explain to the American people why such a militaristic mobilization of their society was needed."[4]

After Joseph Stalin died in March 1953, Georgy Malenkov took leadership of the Soviet Union. Malenkov proposed a "peaceful coexistence" with the West, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill proposed a summit of the world leaders. Fearing that the summit would delay the rearmament of West Germany, and skeptical of Malenkov's intentions and ability to stay in power, the Eisenhower administration nixed the summit idea. In April, Eisenhower delivered his "Chance for Peace speech," in which he called for an armistice in Korea, free elections to re-unify Germany, the "full independence" of Eastern European nations, and United Nations control of atomic energy. Though well received in the West, the Soviet leadership viewed Eisenhower's speech as little more than propaganda. In 1954, a more confrontational leader, Nikita Khrushchev, took charge in the Soviet Union. Eisenhower became increasingly skeptical of the possibility of cooperation with the Soviet Union after it refused to support his Atoms for Peace proposal, which called for the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the creation of nuclear power plants.[5]

National security policy

Eisenhower unveiled the New Look, his first national security policy, on October 30, 1953. It reflected his concern for balancing the Cold War military commitments of the United States with the nation's financial resources. The policy emphasized reliance on strategic nuclear weapons, rather than conventional military power, to deter both conventional and nuclear military threats.[6] The U.S. military developed a strategy of nuclear deterrence based upon the triad of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), strategic bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs).[7] Throughout his presidency, Eisenhower insisted on having plans to retaliate, fight, and win a nuclear war against the Soviets, although he hoped he would never feel forced to use such weapons.[8]

As the ground war in Korea ended, Eisenhower sharply reduced the reliance on expensive Army divisions. Historian Saki Dockrill argues that his long-term strategy was to promote the collective security of NATO and other American allies, strengthen the Third World against Soviet pressures, avoid another Korea, and produce a climate that would slowly and steadily weaken Soviet power and influence. Dockrill points to Eisenhower's use of multiple assets against the Soviet Union:

Eisenhower knew that the United States had many other assets that could be translated into influence over the Soviet bloc—its democratic values and institutions, its rich and competitive capitalist economy, its intelligence technology and skills in obtaining information as to the enemy's capabilities and intentions, its psychological warfare and covert operations capabilities, its negotiating skills, and its economic and military assistance to the Third World.[9]

End of the Korean War

During his campaign, Eisenhower said he would go to Korea to end the Korean War, which had broken out in 1950 after North Korea invaded South Korea.[10] The U.S. had joined the war to prevent the fall of South Korea, later expanding the mission to include victory over the Communist regime in North Korea.[11] The intervention of Chinese forces in late 1950 led to a protracted stalemate around the 38th parallel north.[12]

Truman had begun peace talks in mid-1951, but the issue of North Korean and Chinese prisoners remained a sticking point. Over 40,000 prisoners from the two countries refused repatriation, but North Korea and China nonetheless demanded their return.[13] Upon taking office, Eisenhower demanded a solution, warning China that he would use nuclear weapons if the war continued.[14] China came to terms, and an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953 as the Korean Armistice Agreement. Historian Edward C. Keefer says that in accepting the American demands that POWs could refuse to return to their home country, "China and North Korea still swallowed the bitter pill, probably forced down in part by the atomic ultimatum."[15] Historian and government advisor McGeorge Bundy states that while the threat to use nuclear weapons was not empty, neither did it ever reach the point of trying to obtain consent to their use from U.S. allies.[16]

The armistice led to decades of uneasy peace between North Korea and South Korea. The United States and South Korea signed a defensive treaty in October 1953, and the U.S. would continue to station thousands of soldiers in South Korea long after the end of the Korean War.[17]

Covert actions

Eisenhower, while accepting the doctrine of containment, sought to counter the Soviet Union through more active means as detailed in the State-Defense report NSC 68.[18] The Eisenhower administration and the Central Intelligence Agency used covert action to interfere with suspected communist governments abroad. An early use of covert action was against the elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mosaddeq, resulting in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. The CIA also instigated the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état by the local military that overthrew president Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, whom U.S. officials viewed as too friendly toward the Soviet Union. Critics have produced conspiracy theories about the causal factors, but according to historian Stephen M. Streeter, CIA documents show the United Fruit Company (UFCO) played no major role in Eisenhower's decision, that the Eisenhower administration did not need to be forced into the action by any lobby groups, and that Soviet influence in Guatemala was minimal.

Streeter identifies three major interpretive perspectives, "Realist," "Revisionist," and "Postrevisionist':

- Realists, who concern themselves primarily with power politics, have generally blamed the Cold War on an aggressive, expansionist Soviet empire. Because realists believe that Arbenz was a Soviet puppet, they view his overthrow as the necessary rollback of communism in the Western Hemisphere. Revisionists, who place the majority of the blame for the Cold War on the United States, emphasize how Washington sought to expand overseas markets and promote foreign investment, especially in the Third World. Revisionists allege that because the State Department came to the rescue of the UFCO, the U.S. intervention in Guatemala represents a prime example of economic imperialism. Postrevisionists, a difficult group to define precisely, incorporate both strategic and economic factors in their interpretation of the Cold War. They tend to agree with revisionists on the issue of Soviet responsibility, but they are much more concerned with explaining the cultural and ideological influences that warped Washington's perception of the Communist threat. According to postrevisionists, the Eisenhower administration officials turned against Arbenz because they failed to grasp that he represented a nationalist rather than a communist.[19][20][21]

Defeating the Bricker Amendment

In January 1953, Senator John W. Bricker of Ohio re-introduced the Bricker Amendment, which would limit the president's treaty making power and ability to enter into executive agreements with foreign nations. Fears that the steady stream of post-World War II-era international treaties and executive agreements entered into by the U.S. were undermining the nation's sovereignty united isolationists, conservative Democrats, most Republicans, and numerous professional groups and civic organizations behind the amendment.[22][23] Believing that the amendment would weaken the president to such a degree that it would be impossible for the U.S. to exercise leadership on the global stage,[24] Eisenhower worked with Senate Minority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson to defeat Bricker's proposal.[25] Although the amendment started out with 56 co-sponsors, it went down to defeat in the U.S. Senate in 1954 on 42–50 vote. Later in 1954, a watered-down version of the amendment missed the required two-thirds majority in the Senate by one vote.[26] This episode proved to be the last hurrah for the isolationist Republicans, as younger conservatives increasingly turned to an internationalism based on aggressive anti-communism, typified by Senator Barry Goldwater.[27]

Europe

Eisenhower sought troop reductions in Europe by sharing of defense responsibilities with NATO allies. Europeans, however, never quite trusted the idea of nuclear deterrence and were reluctant to shift away from NATO into a proposed European Defence Community (EDC).[28] Like Truman, Eisenhower believed that the rearmament of West Germany was vital to NATO's strategic interests. The administration backed an arrangement, devised by Churchill and British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, in which West Germany was rearmed and became a fully sovereign member of NATO in return for promises not establish atomic, biological, or chemical weapons programs. European leaders also created the Western European Union to coordinate European defense. In response to the integration of West Germany into NATO, Eastern bloc leaders established the Warsaw Pact. Austria, which had been jointly-occupied by the Soviet Union and the Western powers, regained its sovereignty with the 1955 Austrian State Treaty. As part of the arrangement that ended the occupation, Austria declared its neutrality after gaining independence.[29]

The Eisenhower administration placed a high priority on undermining Soviet influence on Eastern Europe, and escalated a propaganda war under the leadership of Charles Douglas Jackson. The United States dropped over 300,000 propaganda leaflets in Eastern Europe between 1951 and 1956, and Radio Free Europe sent broadcasts throughout the region. A 1953 uprising in East Germany briefly stoked the administration's hopes of a decline in Soviet influence, but the USSR quickly crushed the insurrection. In 1956, a major uprising broke out in Hungary. After Hungarian leader Imre Nagy promised the establishment of a multiparty democracy and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev dispatched 60,000 soldiers into Hungary to crush the rebellion. The United States strongly condemned the military response but did not take direct action, disappointing many Hungarian revolutionaries. After the revolution, the United States shifted from encouraging revolt to seeking cultural and economic ties as a means of undermining Communist regimes.[30] Among the administration's cultural diplomacy initiatives were continuous goodwill tours by the "soldier-musician ambassadors" of the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra.[31][32][33]

Spain and Italy

In 1953, Eisenhower opened relations with Spain under dictator Francisco Franco. Despite its undemocratic nature, Spain's strategic position in light of the Cold War and anti-communist position led Eisenhower to build a trade and military alliance with the Spanish through the Pact of Madrid. These relations brought an end to Spain's isolation after World War II, which in turn led to a Spanish economic boom known as the Spanish miracle.[34]

One of Eisenhower's most visible diplomatic appointments was Clare Boothe Luce, who served as the Ambassador to Italy from 1953 to 1956. She was a famous playwright, prominent American Catholic, and the wife of Henry Luce, the dynamic publisher of the highly influential TIME and LIFE magazines. Her mission was to give a favorable impression of the United States to the Italians and help defeat communism in that country. Luce's frontal attack on communist power, while often counterproductive, was also balanced by her discerning use of diplomacy, which deeply influenced the interplay between Italy's domestic and foreign policies. She promoted American popular culture and critically evaluated its effects. She often met with political and cultural leaders who demanded autonomy and mildly criticized American culture.[35][36]

East Asia and Southeast Asia

After the end of World War II, the Communist Việt Minh launched an insurrection against the French-supported State of Vietnam.[37] Seeking to bolster France and prevent the fall of Vietnam to Communism, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations played a major role in financing French military operations in Vietnam.[38] In 1954, the French requested the United States to intervene in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, which would prove to be the climactic battle of the First Indochina War. Seeking to rally public support for the intervention, Eisenhower articulated the domino theory, which held that the fall of Vietnam could lead to the fall of other countries. As France refused to commit to granting independence to Vietnam, Congress refused to approve of an intervention in Vietnam, and the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. At the contemporaneous Geneva Conference, Dulles convinced Chinese and Soviet leaders to pressure Viet Minh leaders to accept the temporary partition of Vietnam; the country was divided into a Communist northern half (under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh) and a non-Communist southern half (under the leadership of Ngo Dinh Diem).[37] Despite some doubts about the strength of Diem's government, the Eisenhower administration directed aid to South Vietnam in hopes of creating a bulwark against further Communist expansion.[39] With Eisenhower's approval, Diem refused to hold elections to re-unify Vietnam; those elections had been scheduled for 1956 as part of the agreement at the Geneva Conference.[40]

Eisenhower's commitment in South Vietnam was part of a broader program to contain China and the Soviet Union in East Asia. In 1954, the United States and seven other countries created the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), a defensive alliance dedicated to preventing the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia. In 1954, China began shelling tiny islands off the coast of Mainland China which were controlled by the Republic of China (ROC). The shelling nearly escalated to nuclear war as Eisenhower considered using nuclear weapons to prevent the invasion of Taiwan, the main island controlled by the ROC. The crisis ended when China ended the shelling and both sides agreed to diplomatic talks; a second crisis in 1958 would end in a similar fashion. During the first crisis, the United States and the ROC signed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty, which committed the United States to the defense of Taiwan.[41] The CIA also supported dissidents in the 1959 Tibetan uprising, but China crushed the uprising.[42]

Middle East

The Middle East became increasingly important to U.S. foreign policy during the 1950s. After the 1953 Iranian coup, the U.S. supplanted Britain as the most influential ally of Iran. Eisenhower encouraged the creation of the Baghdad Pact, a military alliance consisting of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan. As it did in several other regions, the Eisenhower administration sought to establish stable, friendly, anti-Communist regimes in the Arab World. The U.S. attempted to mediate the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but Israel's unwillingness to give up its gains from the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and Arab hostility towards Israel prevented any agreement.[43]

Suez crisis

In 1952, a revolution led by Gamal Abdel Nasser had overthrown the pro-British Egyptian government. After taking power as Prime Minister of Egypt in 1954, Nasser played the Soviet Union and the United States against each other, seeking aid from both sides. Eisenhower sought to bring Nasser into the American sphere of influence through economic aid, but Nasser's Arab nationalism and opposition to Israel served as a source of friction between the United States and Egypt. One of Nasser's main goals was the construction of the Aswan Dam, which would provide immense hydroelectric power and help irrigate much of Egypt. Eisenhower attempted to use American aid for the financing of the construction of the dam as leverage for other areas of foreign policy, but aid negotiations collapsed. In July 1956, just a week after the collapse of the aid negotiations, Nasser nationalized the British-run Suez Canal, sparking the Suez Crisis. [44]

The British strongly protested the nationalization, and formed a plan with France and Israel to capture the canal.[45] Eisenhower opposed military intervention, and he repeatedly told British Prime Minister Anthony Eden that the U.S. would not tolerate an invasion.[46] Though opposed to the nationalization of the canal, Eisenhower feared that a military intervention would disrupt global trade and alienate Middle Eastern countries from the West.[47] Israel attacked Egypt in October 1956, quickly seizing control of the Sinai Peninsula. France and Britain launched air and naval attacks after Nasser refused to renounce Egypt's nationalization of the canal. Nasser responded by sinking dozens of ships, preventing operation of the canal. Angered by the attacks, which risked sending Arab states into the arms of the Soviet Union, the Eisenhower administration proposed a cease fire and used economic pressure to force France and Britain to withdraw.[48] The incident marked the end of British and French dominance in the Middle East and opened the way for greater American involvement in the region.[49] In early 1958, Eisenhower used the threat of economic sanctions to coerce Israel into withdrawing from the Sinai Peninsula, and the Suez Canal resumed operations under the control of Egypt.[50]

Eisenhower Doctrine

In response to the power vacuum in the Middle East following the Suez Crisis, the Eisenhower administration developed a new policy designed to stabilize the region against Soviet threats or internal turmoil. Given the collapse of British prestige and the rise of Soviet interest in the region, the president informed Congress on January 5, 1957 that it was essential for the U.S. to accept new responsibilities for the security of the Middle East. Under the policy, known as the Eisenhower Doctrine, any Middle Eastern country could request American economic assistance or aid from U.S. military forces if it was being threatened by armed aggression. Though Eisenhower found it difficult to convince leading Arab states or Israel to endorse the doctrine, but he applied the new doctrine by dispensing economic aid to shore up the Kingdom of Jordan, encouraging Syria's neighbors to consider military operations against it, and sending U.S. troops into Lebanon to prevent a radical revolution from sweeping over that country.[51] The troops sent to Lebanon never saw any fighting, but the deployment marked the only time during Eisenhower's presidency when U.S. troops were sent abroad into a potential combat situation.[52]

Though U.S. aid helped Lebanon and Jordan avoid revolution, the Eisenhower doctrine enhanced Nasser's prestige as the preeminent Arab nationalist. Partly as a result of the bungled U.S. intervention in Syria, Nasser established the short-lived United Arab Republic, a political union between Egypt and Syria.[53] The U.S. also lost a sympathetic Middle Eastern government due to the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état, which saw King Faisal I replaced by General Abd al-Karim Qasim as the leader of Iraq.[54]

South Asia

The 1947 partition of British India created two new independent states, India and Pakistan. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru pursued a non-aligned policy in the Cold War, and frequently criticized U.S. policies. Largely out of a desire to build up military strength against the more populous India, Pakistan sought close relations with the United States, joining both the Baghdad Pact and SEATO. This U.S.–Pakistan alliance alienated India from the United States, causing India to move towards the Soviet Union. In the late 1950s, the Eisenhower administration sought closer relations with India, sending aid to stem the 1957 Indian economic crisis. By the end of his administration, relations between the United States and India had moderately improved, but Pakistan remained the main U.S. ally in South Asia.[55]

Latin America

For much of his administration, Eisenhower largely continued the policy of his predecessors in Latin America, supporting U.S.-friendly governments regardless of whether they held power through authoritarian means. The Eisenhower administration expanded military aid to Latin America, and used Pan-Americanism as a tool to prevent the spread of Soviet influence. In the late 1950s, several Latin American governments fell, partly due to a recession in the United States.[56]

Cuba was particularly close to the United States, and 300,000 American tourists visited Cuba each year in the late 1950s. Cuban President Fulgencio Batista sought close ties with both the U.S. government and major U.S. companies, and American organized crime also had a strong presence in Cuba.[57] In January 1959, the Cuban Revolution ousted Batista. The new regime, led by Fidel Castro, quickly legalized the Communist Party of Cuba, sparking U.S. fears that Castro would align with the Soviet Union. When Castro visited the United States in April 1959, Eisenhower refused to meet with him, delegating the task to Nixon.[58] In the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, the Eisenhower administration began to encourage democratic government in Latin America and increased economic aid to the region. As Castro drew closer to the Soviet Union, the U.S. broke diplomatic relations, launched a near-total embargo, and began preparations for an invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles.[59]

Eisenhower also launched operation wetback to stop illegal immigration.

Ballistic missiles and arms control

The United States had tested the first atom bomb in 1945, but both sides started building large nuclear stockpiles during the 1950s. During Eisenhower's presidency, the Cold War arms race shifted from nuclear weapons to delivery systems, with the U.S. starting with a large lead in very long-range bombers. The Soviets emphasized building ballistic intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). They fired their first ICBM in August 1957, followed by a highly public launching of the Sputnik 1 satellite in October 1957. The launch of the Sputnik energized the American missile program, and the U.S. fired its first ICBM in December 1957. The U.S. brought Titan and Atlas ICBMs into service in 1959, and in 1960 built Polaris submarines capable of underwater launches.[60][61][62]

In January 1956 the United States Air Force began developing the Thor, a 1,500 miles (2,400 km) Intermediate-range ballistic missile. The program proceeded quickly, and beginning in 1958 the first of 20 Royal Air Force Thor squadrons became operational in the United Kingdom. This was the first experiment at sharing strategic nuclear weapons in NATO and led to other placements abroad of American nuclear weapons.[63] Critics at the time, led by Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy levied charges to the effect that there was a "missile gap", that is, the U.S. had fallen militarily behind the Soviets because of their lead in space. Historians now discount those allegations, although they agree that Eisenhower did not effectively respond to his critics.[64] In fact, the Soviet Union did not deploy ICBMs until after Eisenhower left office, and the U.S. retained an overall advantage in nuclear weaponry. Eisenhower was aware of the American advantage in ICBM development because of intelligence gathered by U-2 planes, which had begun flying over the Soviet Union in 1956.[65]

The administration decided the best way to minimize the proliferation of nuclear weapons was to tightly control knowledge of gas-centrifuge technology, which was essential to turn ordinary uranium and to weapons-grade uranium. American diplomats by 1960 reached agreement with the German, Dutch, and British governments to limit access to the technology. The four-power understanding on gas-centrifuge secrecy would last until 1975, when scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan took the Dutch centrifuge technology to Pakistan.[66]

France also sought American help in developing nuclear weapons; Eisenhower rejected the overtures for four reasons. Before 1958, he was troubled by the political instability of the French Fourth Republic and worried that it might use nuclear weapons to its colonial wars in Vietnam and Algeria. De Gaulle brought stability to the Fifth Republic in 1958, but Eisenhower knew him too well from the war years. De Gaulle wanted to challenge the Anglo-Saxon monopoly on Western weapons. Eisenhower feared his grandiose plans to use the bombs to restore French grandeur would weaken NATO. Furthermore, Eisenhower wanted to discourage the proliferation of nuclear arms anywhere.[67]

U-2 Crisis

U.S. and Soviet leaders met at the 1955 Geneva Summit, the first such summit since the 1945 Potsdam Conference. No progress was made on major issues; the two sides had major differences on German policy, and the Soviets dismissed Eisenhower's "Open Skies" proposal.[68] Despite the lack of agreement on substantive issues, the conference marked the start of a minor thaw in Cold War relations.[69] Kruschev toured the United States in 1959, and he and Eisenhower conducted high-level talks regarding nuclear disarmament and the status of Berlin. Eisenhower wanted limits on nuclear weapons testing and on-site inspections of nuclear weapons, while Kruschev initially sought the total elimination of nuclear arsenals. Both wanted to limit total military spending and prevent nuclear proliferation, but Cold War tensions made negotiations difficult.[70] Towards the end of his second term, Eisenhower was determined to reach a nuclear test ban treaty as part of an overall move towards détente with the Soviet Union. Khrushchev had also become increasingly interested in reaching an accord, partly due to the growing Sino-Soviet split.[71] By 1960, the major unresolved issue was on-site inspections, as both sides sought nuclear test bans. Hopes for reaching a nuclear agreement at a May 1960 summit in Paris were derailed by the downing of an American U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union.[70]

The Eisenhower administration, initially thinking the pilot had died in the crash, authorized the release of a cover story claiming that the plane was a "weather research aircraft" which had unintentionally strayed into Soviet airspace after the pilot had radioed "difficulties with his oxygen equipment" while flying over Turkey.[72] Further, Eisenhower said that his administration had not been spying on the Soviet Union; when the Soviets produced the pilot, Captain Francis Gary Powers, the Americans were caught misleading the public, and the incident resulted in international embarrassment for the United States.[73][74] The Senate Foreign Relations Committee held a lengthy inquiry into the U-2 incident.[75] During the Paris Summit, Eisenhower accused Khrushchev "of sabotaging this meeting, on which so much of the hopes of the world have rested,"[76] Later, Eisenhower stated the summit had been ruined because of that "stupid U-2 business."[75]

International trips

Eisenhower made one international trip while president-elect, to South Korea, December 2–5, 1952; he visited Seoul and the Korean combat zone. He also made 16 international trips to 26 nations during his presidency.[77] Between August 1959 and June 1960, he undertook five major tours, travelling to Europe, Southeast Asia, South America, the Middle East, and Southern Asia. On his "Flight to Peace" Goodwill tour, in December 1959, the President visited 11 nations including five in Asia, flying 22,000 miles in 19 days.

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | December 2–5, 1952 | Seoul | Visit to Korean combat zone. (Visit made as President-elect.) | |

| 2 | October 19, 1953 | Nueva Ciudad Guerrero | Dedication of Falcon Dam, with President Adolfo Ruiz Cortines.[78] | |

| 3 | November 13–15, 1953 | Ottawa | State visit. Met with Governor General Vincent Massey and Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. Addressed Parliament. | |

| 4 | December 4–8, 1953 | Hamilton | Attended the Bermuda Conference with Prime Minister Winston Churchill and French Prime Minister Joseph Laniel. | |

| 5 | July 16–23, 1955 | Geneva | Attended the Geneva Summit with British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, French Premier Edgar Faure and Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin. | |

| 6 | July 21–23, 1956 | Panama City | Attended the meeting of the presidents of the American republics. | |

| 7 | March 20–24, 1957 | Hamilton | Met with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. | |

| 8 | December 14–19, 1957 | Paris | Attended the First NATO summit. | |

| 9 | July 8–11, 1958 | Ottawa | Informal visit. Met with Governor General Vincent Massey and Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Addressed Parliament. | |

| 10 | February 19–20, 1959 | Acapulco | Informal meeting with President Adolfo López Mateos. | |

| 11 | June 26, 1959 | Montreal | Joined Queen Elizabeth II in ceremony opening the St. Lawrence Seaway. | |

| 12 | August 26–27, 1959 | Bonn | Informal meeting with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and President Theodor Heuss. | |

| August 27 – September 2, 1959 |

London, Balmoral, Chequers |

Informal visit. Met Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Queen Elizabeth II. | ||

| September 2–4, 1959 | Paris | Informal meeting with President Charles de Gaulle and Italian Prime Minister Antonio Segni. Addressed North Atlantic Council. | ||

| September 4–7, 1959 | Culzean Castle | Rested before returning to the United States. | ||

| 13 | December 4–6, 1959 | Rome | Informal visit. Met with President Giovanni Gronchi. | |

| December 6, 1959 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope John XXIII. | ||

| December 6–7, 1959 | Ankara | Informal visit. Met with President Celâl Bayar. | ||

| December 7–9, 1959 | Karachi | Informal visit. Met with President Ayub Khan. | ||

| December 9, 1959 | Kabul | Informal visit. Met with King Mohammed Zahir Shah. | ||

| December 9–14, 1959 | New Delhi, Agra |

Met with President Rajendra Prasad and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| December 14, 1959 | Tehran | Met with Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| December 14–15, 1959 | Athens | Official visit. Met with King Paul and Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| December 17, 1959 | Tunis | Met with President Habib Bourguiba. | ||

| December 18–21, 1959 | Toulon, Paris |

Conference with President Charles de Gaulle, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. | ||

| December 21–22, 1959 | Madrid | Met with Generalissimo Francisco Franco. | ||

| December 22, 1959 | Casablanca | Met with King Mohammed V. | ||

| 14 | February 23–26, 1960 | Brasília, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo |

Met with President Juscelino Kubitschek. Addressed Brazilian Congress. | |

| February 26–29, 1960 | Buenos Aires, Mar del Plata, San Carlos de Bariloche |

Met with President Arturo Frondizi. | ||

| February 29 – March 2, 1960 |

Santiago | Met with President Jorge Alessandri. | ||

| March 2–3, 1960 | Montevideo | Met with President Benito Nardone. Returned to the U.S. via Buenos Aires and Suriname. | ||

| 15 | May 15–19, 1960 | Paris | Conference with President Charles de Gaulle, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. | |

| May 19–20, 1960 | Lisbon | Official visit. Met with President Américo Tomás. | ||

| 16 | June 14–16, 1960 | Manila | State visit. Met with President Carlos P. Garcia. | |

| June 18–19, 1960 | Taipei | State visit. Met with President Chiang Kai-shek. | ||

| June 19–20, 1960 | Seoul | Met with Prime Minister Heo Jeong. Addressed the National Assembly. | ||

| 17 | October 24, 1960 | Ciudad Acuña | Informal visit. Met with President Adolfo López Mateos. |

South Korea 1952

South Korea 1952 Geneva Summit 1955

Geneva Summit 1955 Bonn, Germany 1959

Bonn, Germany 1959 Turkey 1959

Turkey 1959 Afghanistan 1959

Afghanistan 1959 India 1959

India 1959 Iran 1959

Iran 1959 Spain 1959

Spain 1959 Brazil 1960

Brazil 1960 Argentina 1960

Argentina 1960.jpg.webp) Uruguay 1960

Uruguay 1960.jpg.webp) Taiwan 1960

Taiwan 1960

References

- Johnson 2018, pp. 447–448.

- Herring 2008, pp. 651–652.

- Herring 2008, p. 665.

- William I Hitchcock (2018). The Age of Eisenhower: America and the World in the 1950s. Simon and Schuster. p. 109. ISBN 9781451698428.

- Wicker, pp. 22–24, 44.

- Saki Dockrill, Eisenhower’s New-Look National Security Policy, 1953–61 (1996).

- Roman, Peter J. (1996). Eisenhower and the Missile Gap. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801427978.

- Chernus, Ira (March 17, 2008). "The Real Eisenhower". History News Network.

- Dockrill, Saki (2000). "Dealing with Soviet Power and Influence: Eisenhower's Management of U.S. National Security". Diplomatic History. 24 (2): 345–352. doi:10.1111/0145-2096.00218.

- Patterson, pp. 208–210, 261.

- James I. Matray, "Truman's Plan for Victory: National Self-Determination and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel Decision in Korea." Journal of American History 66.2 (1979): 314-333. online

- Patterson, pp. 210–215, 223–233.

- Patterson, pp. 232–233.

- Jackson, Michael Gordon (2005). "Beyond Brinkmanship: Eisenhower, Nuclear War Fighting, and Korea, 1953–1968". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 35 (1): 52–75. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2004.00235.x.

- Edward C. Keefer, "President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the End of the Korean War" Diplomatic History (1986) 10#3: 267–289; quote follows footnote 33.

- Bundy, pp. 238–243.

- Herring 2008, pp. 660–661.

- Stephen E. Ambrose (2012). Ike's Spies: Eisenhower and the Espionage Establishment. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 172. ISBN 9780307946614.

- Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). "Interpreting the 1954 U.S. Intervention in Guatemala: Realist, Revisionist, and Postrevisionist Perspectives". History Teacher. 34 (1): 61–74. doi:10.2307/3054375. JSTOR 3054375. S2CID 141471098.

- Stephen M. Streeter, Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961 (Ohio UP, 2000), pp. 7–9, 20.

- Stephen G. Rabe (1988). Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. UNC Press Books. pp. 62–5. ISBN 9780807842041.

- Parker, John J. (April 1954). "The American Constitution and the Treaty Making Power". Washington University Law Quarterly. 1954 (2): 115–131. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Raimondo, Justin. "The Bricker Amendment". Redwood City, California: Randolph Bourne Institute. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Ciment, James (2015). Postwar America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 978-1317462354.

- Herring 2008, p. 657.

- Tananbaum, Duane A. (1985). "The Bricker Amendment Controversy: Its Origins and Eisenhower's Role". Diplomatic History. 9 (1): 73–93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1985.tb00523.x.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (Spring 1992). "The Last Hurrah of Conservative Isolationism: Eisenhower, Congress, and the Bricker Amendment". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 22 (2): 337–349. JSTOR 27550951.

- Dockrill, Saki (1994). "Cooperation and suspicion: The United States' alliance diplomacy for the security of Western Europe, 1953–54". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 5 (1): 138–182. doi:10.1080/09592299408405912.

- Herring 2008, pp. 668–670.

- Herring 2008, pp. 664–668.

- Dance for Export: Cultural Diplomacy and the Cold War Naima Prevots. Wesleyan University Press, CT. 1998 p. 11 Dwight D. Eisenhower requests funds to present the best American cultural achievements abroad on books.google.com

- 7th Army Symphony Chronology – General Palmer authorizes Samuel Adler to found the orchestra in 1952 on 7aso.org

- A Dictionary for the Modern Composer, Emily Freeman Brown, Scarecrow Press, Oxford, 2015, p. 311 ISBN 9780810884014 Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra founded by Samuel Adler in 1952 on https://books.google.com

- Stanley G. Payne (2011). The Franco Regime, 1936–1975. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 458. ISBN 9780299110734.

- Alessandro Brogi, "Ambassador Clare Boothe Luce and the evolution of psychological warfare in Italy." Cold War History 12.2 (2012): 269–294.

- Mario Del Pero, "The United States and" psychological warfare" in Italy, 1948–1955." Journal of American History 87.4 (2001): 1304–1334. online

- Herring 2008, pp. 661–662.

- Patterson, pp. 292–293.

- Pach & Richardson, pp. 97–98.

- Patterson, pp. 296–298.

- Herring 2008, pp. 663–664, 693.

- Herring 2008, p. 692.

- Herring 2008, pp. 672–674.

- Pach & Richardson, pp. 126–128.

- Herring 2008, pp. 674–675.

- See Anthony Eden, and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Eden-Eisenhower Correspondence, 1955–1957 (U of North Carolina Press, 2006)

- Pach & Richardson, pp. 129–130.

- Herring 2008, pp. 675–676.

- Cole C. Kingseed (1995). Eisenhower and the Suez Crisis of 1956. Louisiana State U.P. ISBN 9780807140857.

- Pach & Richardson, p. 163.

- Hahn, Peter L. (March 2006). "Securing the Middle East: The Eisenhower Doctrine of 1957". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 36 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00285.x.

- Patterson, p. 423.

- Herring 2008, pp. 678–679.

- Pach & Richardson, pp. 191–192.

- Herring 2008, pp. 679–681.

- Herring 2008, pp. 683–686.

- Herring 2008, pp. 686–67.

- Wicker, pp. 108–109.

- Herring 2008, pp. 688–689.

- P.M.H. Bell, The World since 1845: It international history (2001) p. 156

- William L. Hitchcock, The Age of Eisenhower (2018), pp 169-75, 380-406.

- Yanek Mieczkowski, Eisenhower's Sputnik moment: The race for space and world prestige (Cornell UP, 2013).

- Melissen, Jan (June 1992). "The Thor saga: Anglo‐American nuclear relations, US IRBM development and deployment in Britain, 1955–1959". Journal of Strategic Studies. 15 (2): 172–207. doi:10.1080/01402399208437480. ISSN 0140-2390.

- Peter J. Roman, Eisenhower and the Missile Gap (1996)

- Patterson, pp. 419–420.

- Burr, William (2015). "The 'Labors of Atlas, Sisyphus, or Hercules'? US Gas-Centrifuge Policy and Diplomacy, 1954–60". International History Review. 37 (3): 431–457. doi:10.1080/07075332.2014.918557.

- Keith W. Baum, "Two's Company, Three's a Crowd: The Eisenhower Administration, France, and Nuclear Weapons." Presidential Studies Quarterly 20#2 (1990): 315–328. in JSTOR

- Herring 2008, p. 670.

- Patterson, pp. 303–304.

- Herring 2008, pp. 696–698.

- Pach & Richardson, pp. 214–215.

- Fontaine, André; translator R. Bruce (1968). History of the Cold War: From the Korean War to the present. History of the Cold War. 2. Pantheon Books. p. 338.

- Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-465-04195-4.

- Walsh, Kenneth T. (June 6, 2008). "Presidential Lies and Deceptions". US News and World Report.

- Bogle, Lori Lynn, ed. (2001). The Cold War. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-0815337218.

- "1960 Year In Review: The Paris Summit Falls Apart". UPI. 1960. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- "Travels of President Dwight D. Eisenhower". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian.

- International Boundary and Water Commission; Falcon Dam Archived 2010-04-08 at the Wayback Machine

Works cited

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1983). Eisenhower. Volume I: Soldier, General of the Army, President–Elect, 1890–1952. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0671440695.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1984). Eisenhower. Volume II: President and Elder Statesman, 1952–1969. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0671605650.

- Bundy, McGeorge (1988). Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-52278-8.

- Dockrill, Saki (1994). "Cooperation and suspicion: The United States' alliance diplomacy for the security of Western Europe, 1953–54". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 5#1: 138–182 online

- Dockrill, Saki. (1996) Eisenhower's New-Look National Security Policy, 1953–61 excerpt

- Herring, George C. (2008). From Colony to Superpower; U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0.

- Hitchcock, William I. The Age of Eisenhower: America and the World in the 1950 (2018). The major scholarly synthesis; 645pp; online review symposium

- Johnson, C. Donald (2018). The Wealth of Nations: A History of Trade Politics in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190865917.

- Kabaservice, Geoffrey (2012). Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199768400.

- Lyon, Peter (1974). Eisenhower: Portrait of the Hero. Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0316540216. online free to borrow

- McMahon, Robert J. "Eisenhower and Third World Nationalism: A Critique of the Revisionists," Political Science Quarterly 101#3 (1986), pp. 453–473, online

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press. LCCN 65-12468.

- Pach, Chester J.; Richardson, Elmo (1991). The Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (Revised ed.). University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0437-1.

- Patterson, James (1996). Grand Expectations: The United States 1945–1974. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195117974.

- Pusey, Merlo J. (1956). Eisenhower The President. Macmillan. LCCN 56-8365.

- Schefter, James (1999). The Race: The uncensored story of how America beat Russia to the Moon. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-49253-9.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. Random House. ISBN 978-1400066933.

- Wicker, Tom (2002). Dwight D. Eisenhower. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6907-5.

Further reading

Biographies

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: Soldier and President (2003). A revision and condensation of his earlier two-volume Eisenhower biography.

- Gellman, Irwin F. The President and the Apprentice: Eisenhower and Nixon, 1952–1961 (2015).

- Graff, Henry F., ed. The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed. 2002)

- Krieg, Joann P. ed. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Soldier, President, Statesman (1987). 24 essays by scholars.

- Mayer, Michael S. The Eisenhower Years (2009), 1024pp; short biographies by experts of 500 prominent figures, with some primary sources.

- Newton, Jim, Eisenhower: The White House Years (Random House, 2011) online

- Nichols, David A. Eisenhower 1956: The President's Year of Crisis--Suez and the Brink of War (2012).

- Schoenebaum, Eleanora, ed. Political Profiles the Eisenhower Years (1977); 757pp; short political biographies of 501 major players in politics in the 1950s.

Scholarly studies

- Anderson J. W. Eisenhower, Brownell, and the Congress: The Tangled Origins of the Civil Rights Bill of 1956–1957. University of Alabama Press, 1964.

- Burrows, William E. This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age. New York: Random House, 1998. 282pp

- Congressional Quarterly. Congress and the Nation 1945–1964 (1965), Highly detailed and factual coverage of Congress and presidential politics; 1784 pages

- Damms, Richard V. The Eisenhower Presidency, 1953–1961 (2002)

- Eulau Heinz, Class and Party in the Eisenhower Years. Free Press, 1962. voting behavior

- Greene, John Robert. I Like Ike: The Presidential Election of 1952 (2017) excerpt

- Greenstein, Fred I. The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader (1991).

- Harris, Douglas B. "Dwight Eisenhower and the New Deal: The Politics of Preemption" Presidential Studies Quarterly, 27#2 (1997) pp. 333–41 in JSTOR.

- Harris, Seymour E. The Economics of the Political Parties, with Special Attention to Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy (1962)

- Hitchcock, William I. The Age of Eisenhower: America and the World in the 1950 (2018). The major scholarly synthesis; 645pp; online review symposium

- Holbo, Paul S. and Robert W. Sellen, eds. The Eisenhower era: the age of consensus (1974), 196pp; 20 short excerpts from primary and secondary sources online

- Kaufman, Burton I. and Diane Kaufman. Historical Dictionary of the Eisenhower Era (2009), 320pp

- Krieg, Joanne P. ed. Dwight D. Eisenhower: Soldier, President, Statesman (1987), 283–296; online

- Medhurst; Martin J. Dwight D. Eisenhower: Strategic Communicator (Greenwood Press, 1993).

- Olson, James S. Historical Dictionary of the 1950s (2000)

- Pach, Chester J. ed. A Companion to Dwight D. Eisenhower (2017), new essays by experts; stress on historiography.

- Pickett, William B. (1995). Dwight David Eisenhower and American Power. Wheeling, Ill.: Harlan Davidson. ISBN 978-0-88-295918-4. OCLC 31206927.

- Pickett, William B. (2000). Eisenhower Decides to Run: Presidential Politics and Cold War Strategy. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-56-663787-9. OCLC 43953970.

Foreign and military policy

- Andrew, Christopher. For the President’s Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush (1995), pp. 199–256.

- Bose, Meenekshi. Shaping and signaling presidential policy: The national security decision making of Eisenhower and Kennedy (Texas A&M UP, 1998).

- Bowie, Robert R. and Richard H. Immerman, eds. Waging peace: how Eisenhower shaped an enduring cold war strategy (1998) online

- Brands, Henry W. Cold Warriors: Eisenhower's Generation and American Foreign Policy (Columbia UP, 1988).

- Broadwater; Jeff. Eisenhower & the Anti-Communist Crusade (U of North Carolina Press, 1992) online at Questia.

- Bury, Helen. Eisenhower and the Cold War arms race:'Open Skies' and the military-industrial complex (2014).

- Chernus, Ira. Apocalypse Management: Eisenhower and the Discourse of National Insecurity. (Stanford UP, 2008).

- Divine, Robert A. Eisenhower and the Cold War (1981)

- Divine, Robert A. Foreign Policy and U.S. Presidential Elections, 1952–1960 (1974).

- Dockrill, Saki. Eisenhower's New-Look National Security Policy, 1953–61 (1996) excerpt

- Falk, Stanley L. "The National Security Council under Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy." Political Science Quarterly 79.3 (1964): 403-434. online

- Jackson, Michael Gordon (2005). "Beyond Brinkmanship: Eisenhower, Nuclear War Fighting, and Korea, 1953‐1968". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 35 (1): 52–75. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2004.00235.x.

- Kaufman, Burton Ira. Trade and aid: Eisenhower's foreign economic policy, 1953–1961 (1982).

- Melanson, Richard A. and David A. Mayers, eds. Reevaluating Eisenhower: American foreign policy in the 1950s (1989) online

- Rabe, Stephen G. Eisenhower and Latin America: The foreign policy of anticommunism (1988) online

- Rosenberg, Victor. Soviet-American relations, 1953–1960: diplomacy and cultural exchange during the Eisenhower presidency (2005).

- Taubman, William. Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2012), Pulitzer Prize

Historiography

- Broadwater, Jeff. "President Eisenhower and the Historians: Is the General in Retreat?." Canadian Review of American Studies 22.1 (1991): 47–60.

- Burk, Robert. "Eisenhower Revisionism Revisited: Reflections on Eisenhower Scholarship", Historian, Spring 1988, Vol. 50, Issue 2, pp. 196–209

- Catsam, Derek. "The civil rights movement and the Presidency in the hot years of the Cold War: A historical and historiographical assessment." History Compass 6.1 (2008): 314–344. online

- De Santis, Vincent P. "Eisenhower Revisionism," Review of Politics 38#2 (1976): 190–208.

- Hoxie, R. Gordon. "Dwight David Eisenhower: Bicentennial Considerations," Presidential Studies Quarterly 20 (1990), 263.

- Joes, Anthony James. "Eisenhower Revisionism and American Politics," in Joanne P. Krieg, ed., Dwight D. Eisenhower: Soldier, President, Statesman (1987), 283–296; online

- McAuliffe, Mary S. "Eisenhower, the President", Journal of American History 68 (1981), pp. 625–32 JSTOR 1901942

- McMahon, Robert J. "Eisenhower and Third World Nationalism: A Critique of the Revisionists," Political Science Quarterly (1986) 101#3 pp. 453–73 JSTOR 2151625

- Matray, James I (2011). "Korea's war at 60: A survey of the literature". Cold War History. 11 (1): 99–129. doi:10.1080/14682745.2011.545603.

- Melanson, Richard A. and David Mayers, eds. Reevaluating Eisenhower: American Foreign Policy in the 1950s (1987)

- Polsky, Andrew J. "Shifting Currents: Dwight Eisenhower and the Dynamic of Presidential Opportunity Structure," Presidential Studies Quarterly, March 2015.

- Rabe, Stephen G. "Eisenhower Revisionism: A Decade of Scholarship," Diplomatic History (1993) 17#1 pp 97–115.

- Reichard, Gary W. "Eisenhower as President: The Changing View," South Atlantic Quarterly 77 (1978): 265–82

- Schlesinger Jr., Arthur. "The Ike Age Revisited," Reviews in American History (1983) 11#1 pp. 1–11 JSTOR 2701865

- Streeter, Stephen M. "Interpreting the 1954 U.S. Intervention In Guatemala: Realist, Revisionist, and Postrevisionist Perspectives," History Teacher (2000) 34#1 pp 61–74. JSTOR 3054375 online

Primary sources

- Adams, Sherman. Firsthand Report: The Story of the Eisenhower Administration. 1961. by Ike's chief of staff

- Benson, Ezra Taft. Cross Fire: The Eight Years with Eisenhower (1962) Secretary of Agriculture online at Questia

- Brownell, Herbert and John P. Burke. Advising Ike: The Memoirs of Attorney General Herbert Brownell (1993).

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Mandate for Change, 1953–1956, Doubleday and Co., 1963; his memoir

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956–1961, Doubleday and Co., 1965; his memoir

- Papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower The 21 volume Johns Hopkins print edition of Eisenhower's papers includes: The Presidency: The Middle Way (vols. 14–17) and The Presidency: Keeping the Peace (vols. 18–21), his private letters and papers online at subscribing libraries

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Public Papers, covers 1953 through end of term in 1961. based on White House press releases online

- James Campbell Hagerty (1983). Ferrell, Robert H. (ed.). The Diary of James C. Hagerty: Eisenhower in Mid-Course, 1954–1955. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253116253.

- Hughes, Emmet John. The Ordeal of Power: A Political Memoir of the Eisenhower Years. 1963. Ike's speechwriter

- Nixon, Richard M. The Memoirs of Richard Nixon 1978.

- Documentary History of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidency (13 vol. University Publications of America, 1996) online table of contents