Giallo

Giallo (Italian pronunciation: [ˈdʒallo]; plural gialli) is the Italian term designating mystery fiction and thrillers. The word giallo is Italian for yellow.[1] The term derives from a series of cheap paperback mystery and crime thriller novels with yellow covers that were popular in Italy.[2]

In the context of 20th-century literature and film, especially among English speakers and non-Italians in general, giallo refers specifically to a particular Italian thriller-horror genre that has mystery or detective elements and often contains slasher, crime fiction, psychological thriller, psychological horror, sexploitation, and, less frequently, supernatural horror elements.

This particular style of Italian-produced murder mystery thriller-horror film (known more specifically in Italy as giallo all’italiana, roughly translated as "Italian-style giallo") usually blends the atmosphere and suspense of thriller fiction with elements of horror fiction (such as slasher violence) and eroticism (similar to the French fantastique genre), and often involves a mysterious killer whose identity is not revealed until the final act of the film. The genre developed in the mid-to-late 1960s, peaked in popularity during the 1970s, and subsequently declined in commercial mainstream filmmaking over the next few decades, though less prominent examples continue to be produced. It has been considered a predecessor to, and significant influence on, the later American slasher film genre.[3]

Literature

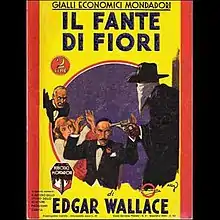

The term giallo ("yellow") derives from a series of crime-mystery pulp novels entitled Il Giallo Mondadori (Mondadori Yellow), published by Mondadori from 1929 and taking its name from the trademark yellow cover background. The series consisted almost exclusively of Italian translations of mystery novels by British and American writers. These included Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, Edgar Wallace, Ed McBain, Rex Stout, Edgar Allan Poe and Raymond Chandler.[2][4][5]

Published as cheap paperbacks, the success of the giallo novels soon began attracting the attention of other Italian publishing houses. They published their own versions and mimicked the yellow covers. The popularity of these series eventually established the word giallo as a synonym in Italian for a mystery novel. In colloquial and media usage in Italy, it also applied to a mysterious or unsolved affair.[2]

Film

In the Italian language, giallo is a broad term that can be translated as "crime novel" including any literary genre involving crime and mystery, with all its sub-genres such as crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery or thriller-horror.[6]

In the movie context, for Italian audiences giallo has come to refer to any kind of murder mystery or horror thriller, regardless of its national origin.[7]

Meanwhile, English-speaking audiences have used the term giallo to refer specifically to a genre of Italian-produced thriller-horror films known to Italian audiences as giallo all'italiana.[4]

In the English-speaking world, Italian giallo films are also sometimes referred to as Spaghetti Thrillers or Spaghetti Slashers, in a similar manner in which Italian Western films and poliziotteschi films from the same period have been referred to as Spaghetti Westerns and Spaghetti crime films, respectively.[8]

The Italian film subgenre began as literal adaptations of the original giallo mystery novels. Directors soon began taking advantage of modern cinematic techniques to create a unique genre that retained the mystery and crime fiction elements of giallo novels but veered more closely into the psychological thriller or psychological horror genres. Many of the typical characteristics of these films were incorporated into the later American slasher genre.[3]

Characteristics

Critics disagree on characterization of a giallo film.[9] Gary Needham wrote:

By its very nature, the giallo challenges our assumptions about how non-Hollywood films should be classified, going beyond the sort of Anglo-American taxonomic imaginary that "fixes" genre both in film criticism and the film industry in order to designate something specific. ...however, despite the giallo's resistance to clear definition there are nevertheless identifiable thematic and stylistic tropes.[2]

These distinct "thematic and stylistic tropes" constitute a loose definition of the genre which is broadly consistent, though various critics have proposed slightly differing characteristic details (which consequently creates some confusion over which films can be considered gialli).[2][9][10] Author Michael Mackenzie has written that gialli can be divided into the male-focused m. gialli, which usually sees a male outsider witness a murder and become the target of the killer when he attempts to solve the crime; and f. gialli, which features a female protagonist who is embroiled in a more sexual and psychological story, typically focusing on her sexuality, psyche and fragile mental state.[11]

Although they often involve crime and detective work, gialli should not be confused with the other popular Italian crime genre of the 1970s, the poliziotteschi, which includes more action-oriented films about violent law enforcement officers (largely influenced by gritty 1970s American films such as Dirty Harry, Death Wish, The Godfather, Serpico, and The French Connection). Directors and stars often moved between both genres and some films could be considered under either banner, such as Massimo Dallamano's 1974 film La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?).[12] Most critics agree that the giallo represents a distinct category with unique features.[13]

Structure

_1.jpg.webp)

Giallo films are generally characterized as gruesome murder-mystery thrillers that combine the suspense elements of detective fiction with scenes of shocking horror, featuring excessive bloodletting, stylish camerawork and often jarring musical arrangements. The archetypal giallo plot involves a mysterious, black-gloved psychopathic killer who stalks and butchers a series of beautiful women.[10] While most gialli involve a human killer, some also feature a supernatural element.[14]

The typical giallo protagonist is an outsider of some type, often a traveler, tourist, outcast, or even an alienated or disgraced private investigator, and frequently a young woman, often a young woman who is lonely or alone in a strange or foreign situation or environment (gialli rarely or less frequently feature law enforcement officers as chief protagonists, which would be more characteristic of the poliziotteschi genre).[2][14] The protagonists are generally or often unconnected to the murders before they begin and are drawn to help find the killer through their role as a witness to one of the murders.[14] The mystery is the identity of the killer, who is often revealed in the climax to be another key character, who conceals his or her identity with a disguise (usually some combination of hat, mask, sunglasses, gloves, and trench coat).[15] Thus, the literary whodunit element of the giallo novels is retained, while being filtered through horror genre elements and Italy's long standing tradition of opera and staged grand guignol drama. The structure of giallo films is also sometimes reminiscent of the so-called "weird menace" pulp magazine horror mystery genre alongside Edgar Allan Poe and Agatha Christie.[16]

It is important to note that while most gialli feature elements of this basic narrative structure, not all do. Some films (for example Mario Bava's 1970 Hatchet for the Honeymoon, which features the killer as the protagonist) may radically alter the traditional structure or abandon it altogether and still be considered gialli due to stylistic or thematic tropes, rather than narrative ones.[14] A consistent element of the genre, is an unusual lack of focus on coherent or logical narrative storytelling. While most have a nominal mystery structure, they may feature bizarre or seemingly nonsensical plot elements and a general disregard for realism in acting, dialogue and character motivation.[4][9][17] As Jon Abrams wrote, "Individually, each [giallo] is like an improv exercise in murder, with each filmmaker having access to a handful of shared props and themes. Black gloves, sexual ambiguity, and psychoanalytic trauma may be at the heart of each film, but the genre itself is without consistent narrative form."[14]

.jpg.webp)

Content

While a shadowy killer and mystery narrative are common to most gialli, the most consistent and notable shared trope in the giallo tradition is the focus on grisly death sequences.[4][14] The murders are invariably violent and gory, featuring a variety of explicit and imaginative attacks. These scenes frequently evoke some degree of voyeurism, sometimes going so far as to present the murder from the first-person perspective of the killer, with the black-gloved hand holding a knife viewed from the killer's point of view.[18][19] The murders often occur when the victim is most vulnerable (showering, taking a bath, or scantily clad); as such, giallo films often include liberal amounts of nudity and sex, almost all of it featuring beautiful young women (actresses associated with the genre include Edwige Fenech, Barbara Bach, Daria Nicolodi, Mimsy Farmer, Barbara Bouchet, Suzy Kendall, Ida Galli and Anita Strindberg).[20] Due to the titillating emphasis on explicit sex and violence, gialli are sometimes categorized as exploitation cinema.[21][22] The association of female sexuality and brutal violence has led some commentators to accuse the genre of misogyny.[4][9][23]

.jpg.webp)

Themes

Gialli are noted for psychological themes of madness, alienation, sexuality, and paranoia.[10] The protagonist is usually a witness to a gruesome crime but frequently finds their testimony subject to skepticism from authority figures, leading to a questioning of their own perception and authority. This ambiguity of memory and perception can escalate to delusion, hallucination, or delirious paranoia. Since gialli protagonists are typically female, this can lead to what writer Gary Needham calls, "...the giallo's inherent pathologising of femininity and fascination with "sick" women."[2] The killer is likely to be mentally-ill as well; giallo killers are almost always motivated by insanity caused by some past psychological trauma, often of a sexual nature (and sometimes depicted in flashbacks).[10][14] The emphasis on madness and subjective perception has roots in the giallo novels (for example, Sergio Martino's Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key was based on Edgar Allan Poe's short story "The Black Cat", which deals with a psychologically unstable narrator) but also finds expression in the tools of cinema: The unsteady mental state of both victim and killer is often mirrored by the wildly-exaggerated style and unfocused narrative common to many gialli.

Writer Mikel J. Koven posits that gialli reflect an ambivalence over the social upheaval modernity brought to Italian culture in the 1960s.

"The changes within Italian culture... can be seen throughout the giallo film as something to be discussed and debated -- issues pertaining to identity, sexuality, increasing levels of violence, women's control over their own lives and bodies, history, the state -- all abstract ideas, which are all portrayed situationally as human stories in the giallo film.[24]

.jpg.webp)

Production

Gialli have been noted for their strong cinematic technique, with critics praising their editing, production design, music and visual style even in the marked absence of other facets usually associated with critical admiration (as gialli frequently lack characterization, believable dialogue, realistic performances and logical coherence in the narrative).[4][9][17] Alexia Kannas wrote of 1968's La morte ha fatto l'uovo (Death Laid an Egg) that "While the film has garnered a reputation for its supreme narrative difficulty (just as many art films have), its aesthetic brilliance is irrefutable", while Leon Hunt wrote that frequent gialli director Dario Argento's work "vacillate[s] between strategies of art cinema and exploitation".[17][21]

Visual style

Gialli are frequently associated with strong technical cinematography and stylish visuals. Critic Maitland McDonagh describes the visuals of Profondo rosso (Deep Red) as, "vivid colors and bizarre camera angles, dizzying pans and flamboyant tracking shots, disorienting framing and composition, fetishistic close-ups of quivering eyes and weird objects (knives, dolls, marbles, braided scraps of wool)..."[25] In addition to the iconic images of shadowy black-gloved killers and gruesome violence, gialli also frequently employ strongly stylized and even occasionally surreal uses of color. Directors Dario Argento and Mario Bava are particularly known for their impressionistic imagery and use of lurid colors, though other giallo directors (notably Lucio Fulci) employed more sedate, realistic styles as well.[20] Due to their typical 1970s milieu, some commentators have also noted their potential for visual camp, especially in terms of fashion and decor.[2][10]

.jpg.webp)

Music

Music has been cited as a key to the genre's unique character;[10] critic Maitland McDonagh describes Profondo rosso (Deep Red) as an "overwhelming visceral experience...equal parts visual...and aural." [25] Writer Anne Billson explains, "The Giallo Sound is typically an intoxicating mix of groovy lounge music, nerve-jangling discord, and the sort of soothing lyricism that belies the fact that it's actually accompanying, say, a slow motion decapitation", (she cites as an example Ennio Morricone's score for 1971's Four Flies on Grey Velvet).[10] Composers of note include Morricone, Bruno Nicolai, and the Italian band Goblin. Other important composers known for their work on giallo films include Piero Umiliani (composer for Five Dolls for an August Moon), Riz Ortolani (The Pyjama Girl Case) and Fabio Frizzi (Sette note in nero a.k.a.The Psychic).[26]

Titles

Gialli often feature lurid or baroque titles, frequently employing animal references or the use of numbers.[10] Examples of the former trend include Sette scialli di seta gialla (Crimes of the Black Cat), Non si sevizia un paperino (Don't Torture a Duckling), La morte negli occhi del gatto (Seven Deaths in the Cat's Eye) and La tarantola dal ventre nero (Black Belly of the Tarantula); while instances of the latter include Sette note in nero (Seven Notes in Black) and The Fifth Cord.[27]

History and development

The first giallo novel to be adapted for film was James M. Cain's The Postman Always Rings Twice, adapted in 1943 by Luchino Visconti as Ossessione.[2] Though the film was technically the first of Mondadori's giallo series to be adapted, its neo-realist style was markedly different from the stylized, violent character which subsequent adaptations would acquire. Condemned by the fascist government, Ossessione was eventually hailed as a landmark of neo-realist cinema, but it did not provoke any further giallo adaptations for almost 20 years.[22]

In addition to the literary giallo tradition, early gialli were also influenced by the German "krimi" films of the early 1960s.[15] Produced by Danish/German studio Rialto Film, these black-and-white crime movies based on Edgar Wallace stories typically featured whodunit mystery plots with a masked killer, anticipating several key components of the giallo movement by several years and despite their link to giallo author Wallace, though, they featured little of the excessive stylization and gore which would define Italian gialli.[28]

The Swedish director Arne Mattsson has also been pointed to as a possible influence, in particular his 1958 film Mannequin in Red. Though the film shares stylistic and narrative similarities with later giallo films (particularly its use of color and its multiple murder plot), there is no direct evidence that subsequent Italian directors had seen it.[29][30]

The first "true" giallo film is usually considered to be Mario Bava's The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963).[2][20] Its title alludes to Alfred Hitchcock's classic The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, remade by Hitchcock in 1956), highlighting the early link between gialli and Anglo-American crime stories. Though shot in black and white and lacking the lurid violence and sexuality which would define later gialli, the film has been credited with establishing the essential structure of the genre: in it, a young American tourist in Rome witnesses a murder, finds her testimony dismissed by the authorities, and must attempt to uncover the killer's identity herself. Bava drew on the krimi tradition as well as the Hitchcockian style referenced in the title, and the film's structure served as a basic template for many of the gialli that would follow.[15]

Bava followed The Girl Who Knew Too Much the next year with the stylish and influential Blood and Black Lace (1964). It introduced a number of elements that became emblematic of the genre: a masked stalker with a shiny weapon in his black-gloved hand who brutally murders a series of glamorous fashion models.[33] Though the movie was not a financial success at the time, the tropes it introduced (particularly its black-gloved killer, provocative sexuality, and bold use of color) would become iconic of the genre."[15][34]

.jpg.webp)

Several similarly-themed crime/thriller movies followed in the next few years, including early efforts from directors Antonio Margheriti (Nude... si muore [Naked You Die] in 1968), Umberto Lenzi (Orgasmo in 1969, Paranoia [A Quiet Place to Kill] and Così dolce... così perversa [So Sweet... So Perverse] in 1969) and Lucio Fulci (Una sull'altra [One on Top of the Other] in 1969), all of whom would go on to become major creative forces in the burgeoning genre. But it was Dario Argento's first feature, in 1970, that turned the giallo into a major cultural phenomenon. That film, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, was greatly influenced by Blood and Black Lace, and introduced a new level of stylish violence and suspense that helped redefine the genre. The film was a box office smash and was widely imitated.[35] Its success provoked a frenzy of Italian films with stylish, violent, and sexually provocative murder plots (Argento alone made three more in the next five years) essentially cementing the genre in the public consciousness. In 1996, director Michele Soavi wrote, "there's no doubt that it was Mario Bava who started the 'spaghetti thrillers' [but] Argento gave them a great boost, a turning point, a new style...'new clothes'. Mario had grown old and Dario made it his own genre... this had repercussions on genre cinema, which, thanks to Dario, was given a new lease on life."[36] The success of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage provoked a decade which saw multiple gialli produced every year. In English-language film circles, the term giallo gradually became synonymous with a heavy, theatrical and stylized visual element.[37]

Popularity and legacy

The giallo genre had its heyday from 1968 through 1978. The most prolific period, however, was the five-year timespan between 1971 and 1975, during which time 96 different gialli were produced (see filmography below). Directors like Bava, Argento, Fulci, Lenzi, and Margheriti continued to produce gialli throughout the 70s and beyond, and were soon joined by other notable directors including Sergio Martino, Paolo Cavara, Armando Crispino, Ruggero Deodato and Bava's son Lamberto Bava. The genre also spread to Spain by the early 70s, resulting in films like La residencia (The House That Screamed) (1969) and Los Ojos Azules de la Muñeca Rota (Blue Eyes Of The Broken Doll) (1973) which had unmistakable giallo characteristics but feature Spanish casts and production talent. Though they preceded the first giallo by a few years, German krimi films continued to be made contemporaneously with early gialli, and were also influenced by their success. As the popularity of krimis declined in Germany, Rialto Film began increasingly pairing with Italian production companies and filmmakers (such as composer Ennio Morricone and director, cinematographer Joe D'Amato, who worked on later krimi films following their successes in Italy). The overlap between the two movements is extensive enough that one of Rialto's final krimi films, Cosa avete fatto a Solange? (What Have You Done to Solange?), features an Italian director and crew and has been called a giallo in its own right.[38][39]

Gialli continued to be produced throughout the 1970s and 1980s, but gradually their popularity diminished and film budgets and production values began shrinking.[40] Director Pupi Avati satirized the genre in 1977 with a slapstick giallo titled Tutti defunti... tranne i morti.[41]

Though the giallo cycle waned in the 1990s and saw few entries in the 2000s, they continue to be produced, notably by Argento (who in 2009 released a film actually titled Giallo, somewhat in homage to his long career in the genre) and co-directors Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani, whose Amer (which uses music from older giallis, including tracks by Morricone and Bruno Nicolai) received a positive critical reception upon its release in 2009.[20] To a large degree, the genre's influence lives on in the slasher films which became enormously popular during the 1980s and drew heavily on tropes developed by earlier gialli.[3]

Influence

The giallo cycle has had a lasting effect on horror films and murder mysteries made outside Italy since the late 1960s as this cinematic style and unflinching content is also at the root of the gory slasher and splatter films that became widely popular in the early 1980s. In particular, two violent shockers from Mario Bava, Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970) and Twitch of the Death Nerve (1971) were especially influential.[37]

Early examples of the giallo effect can be seen in the British film Berserk! (1967) and such American mystery-thrillers as No Way to Treat a Lady (1968), the Oscar-winning Klute (1971),[42] Pretty Maids All in a Row (1971, based on an Italian novel), Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy (1972), Vincent Price's Madhouse (1974), Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)[43] and Brian De Palma's Dressed to Kill (1980).[44][45] Berberian Sound Studio (2012) offers an affectionate tribute to the genre.[46][47]

Director Eli Roth has called the giallo "one of my favorite, favorite subgenres of film,"[48] and specifically cited Sergio Martino's Torso (I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale) (along with the Spanish horror film Who Can Kill a Child?) as influential on his 2005 film Hostel, writing, "...these seventies Italian giallos start off with a group of students that are in Rome, lots of scenes in piazzas with telephoto lenses, and you get the feeling they're being watched. There's this real ominous creepy feeling. The girls are always going on some trip somewhere and they're all very smart. They all make decisions the audience would make."[49]

Filmography

1960s

- The Girl Who Knew Too Much (Mario Bava, 1963; Italian: La ragazza che sapeva troppo) a.k.a.Evil Eye

- Blood and Black Lace (Mario Bava, 1964; Italian: Sei donne per l'assassino / Six Women for the Murderer) a.k.a.Fashion House of Death

- The Monster of London City (Edwin Zbonek, 1964) German krimi film that predated the Italian giallo format

- The Embalmer (1965 film) Dino Tavella, 1965; Italian: Il mostro di Venezia / The Monster of Venice

- Libido (Ernesto Gastaldi, 1965)

- Night of Violence (Roberto Mauri, 1965; Italian: Le notti della violenza / Nights of Violence)

- The Third Eye (Mino Guerrini, 1966; Italian: Il terzo occhio)

- A... For Assassin (Angelo Dorigo, 1966; Italian: A... come Assassino)

- The Murder Clinic (Elio Scardamaglia, 1966; Italian: La lama nel corpo / The Knife in the Body) a.k.a.Nights of Terror, a.k.a.Revenge of the Living Dead

- Omicidio per appuntamento (Mino Guerrini, 1966) a.k.a.Murder by Appointment (translation), a.k.a. Date for a Murder[50]

- The Murderer with the Silk Scarf (Adrian Hoven, 1966; German: Der Mörder mit dem Seidenschal) starring Helga Line[51]

- Assassino senza volto (Angelo Dorigo, 1967; English: Killer Without a Face)

- Col cuore in gola (Tinto Brass, 1967; English: With Heart in Mouth) a.k.a. Deadly Sweet, a.k.a. I Am What I am

- The Sweet Body of Deborah (Romolo Guerrieri, 1968; Italian: Il dolce corpo di Deborah)

- Death Laid an Egg (Giulio Questi, 1968; Italian: La morte ha fatto l'uovo) a.k.a.Plucked, a.k.a.A Curious Way to Love

- A Quiet Place in the Country (Elio Petri, 1968; Italian: Un tranquillo posto di campagna)

- Naked... You Die! (Antonio Margheriti, 1968, Italian: Nude... si muore) a.k.a.The Young, the Evil and the Savage, a.k.a.The Schoolgirl Killer

- Deadly Inheritance (Vittorio Sindoni, 1968; Italian: L'assassino ha le mani pulite / The Killer has Clean Hands)

- A Black Veil for Lisa (Massimo Dallamano, 1968; Italian: La morte non ha sesso / Death Has No Sex)

- Interrabang (Giuliano Biagetti, 1969)

- So Sweet...So Perverse (Umberto Lenzi, 1969; Italian: Così dolce...così perversa)

- The Doll of Satan (Ferruccio Casapinta, 1969; Italian: La bambola di Satana)

- One on Top of the Other (Lucio Fulci, 1969; Italian: Una sull'altra) a.k.a.Perversion Story

- Las trompetas del apocalipsis (Julio Buchs, Spanish, 1969) a.k.a.Trumpets of the Apocalypse, a.k.a.Murder by Music

- The House That Screamed (Narciso Ibáñez Serrador, Spanish,[52] 1969) a.k.a.La residencia, a.k.a. The Boarding School[53]

- Death Knocks Twice (Harald Philipp, 1969; Italian: La morte bussa due volte) a.k.a.Blonde Bait for the Murderer, a.k.a.Hard Women, a.k.a.The Blonde Connection

- Double Face (Riccardo Freda, 1969; Italian: A doppia faccia) a.k.a.Liz et Helen

- Macabre (Javier Setó, 1969; Spanish: Viaje al vacío / Journey to Emptiness) a.k.a.The Invisible Assassin, a.k.a.Shadow of Death

- Orgasmo (Umberto Lenzi, 1969) released in USA as Paranoia

1970s

- The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (Dario Argento, 1970; Italian: L'uccello dalle piume di cristallo) a.k.a.Phantom of Terror, a.k.a.The Gallery Murders

- Hatchet for the Honeymoon (Mario Bava, 1970; Italian: Il rosso segno della follia / The Red Mark of Madness) a.k.a.Blood Brides

- Paranoia (Umberto Lenzi, 1970) released in USA as A Quiet Place to Kill

- Five Dolls for an August Moon (Mario Bava, 1970; Italian: 5 bambole per la luna d'agosto) a.k.a.Island of Terror

- Death Occurred Last Night (Duccio Tessari, 1970; Italian: La morte risale a ieri sera

- A Suitcase for a Corpse (Alfonso Brescia, 1970; Italian: Il tuo dolce corpo da uccidere / Your Sweet Body to Murder)

- Your Hands on My Body (Brunello Rondi, 1970; Italian: Le tue mani sul mio corpo) a.k.a. Schocking [54]

- Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion (Luciano Ercoli, 1970; Italian: Le foto proibite di una signora per bene)

- Kill the Fatted Calf and Roast It (Salvatore Samperi, 1970; Italian: Uccidete il vitello grasso e arrostitelo)

- In the Folds of the Flesh (Sergio Bergonzelli, 1970; Italian: Nelle pieghe della carne)

- The Weekend Murders (Michele Lupo, 1970; Italian: Concerto per pistola solista) a.k.a.The Story of a Crime

- The Man with Icy Eyes (Alberto De Martino, 1971; Italian: L'uomo dagli occhi di ghiaccio)

- A Lizard in a Woman's Skin (Lucio Fulci, 1971; Italian: Una lucertola con la pelle di donna) a.k.a.Schizoid

- The Fifth Cord (Luigi Bazzoni, 1971; Italian: Giornata nera per l'ariete / Black Day for Aries) a.k.a.Evil Fingers

- Oasis of Fear (Umberto Lenzi, 1971; Italian: Un posto ideale per uccidere / An Ideal Place for Murder) a.k.a.Dirty Pictures

- The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (Sergio Martino, 1971; Italian: Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh) a.k.a.Blade of the Ripper, a.k.a.Next!, a.k.a.The Next Victim

- The Case of the Scorpion's Tail (Sergio Martino, 1971; Italian: La coda dello scorpione / Tail of the Scorpion)

- Black Belly of the Tarantula (Paolo Cavara, 1971; Italian: La tarantola dal ventre nero)

- The Cat o' Nine Tails (Dario Argento, 1971; Italian: Il gatto a nove code)[55]

- The Bloodstained Butterfly (Duccio Tessari, 1971; Italian: Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate)

- Four Flies on Grey Velvet (Dario Argento, 1971; Italian: 4 mosche di velluto grigio)[55]

- Marta (José Antonio Nieves Conde, 1971; Italian: ...dopo di che, uccide il maschio e lo divora / Afterwards, It Kills and Devours the Male)

- The Double (Romolo Guerrieri, 1971; Italian: La Controfigura) a.k.a. Love Inferno [56]

- Cross Current (Tonino Ricci, 1971; Italian: Un Omicidio perfetto a termine di legge / A Perfect Murder According to Law)

- The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire (Riccardo Freda, 1971; Italian: L'iguana dalla lingua di fuoco)

- A Bay of Blood (Mario Bava, 1971; Italian: Reazione a catena / Chain Reaction) a.k.a.Twitch of the Death Nerve, a.k.a.Ecologia del delitto / Ecology of Crime, a.k.a.Last House on the Left Part 2

- They Have Changed Their Face (Corrado Farina, 1971; Italian: Hanno cambiato faccia)

- The Designated Victim (Maurizio Lucidi, 1971; Italian: La vittima designata) a.k.a.Murder by Design

- Slaughter Hotel (Fernando Di Leo, 1971; Italian: La bestia uccide a sangue freddo / The Beast Kills in Cold Blood) a.k.a.Asylum Erotica, a.k.a.The Cold-Blooded Beast

- The Fourth Victim (Eugenio Martín, 1971; Italian: In fondo alla piscina / At the Front of the Pool) a.k.a.Death at the Deep End of the Pool, a.k.a.La ultima senora Anderson / The Last Mrs. Anderson

- The Devil Has Seven Faces (Osvaldo Civirani, 1971; Italian: Il diavolo ha sette facce) a.k.a.The Devil with Seven Faces

- Jack the Ripper of London (José Luis Madrid, 1971; Spanish: Jack el destripador de Londres) a.k.a.Seven Murders for Scotland Yard, a.k.a.Seven Corpses for Scotland Yard

- Death Walks on High Heels (Luciano Ercoli, 1971; Italian: La morte cammina con i tacchi alti)

- The Short Night of the Glass Dolls (Aldo Lado, 1971; Italian: La corta notte delle bambole di vetro) a.k.a.Paralyzed

- Cold Eyes of Fear (Enzo G. Castellari, 1971; Italian: Gli occhi freddi della paura) a.k.a.Desperate Moments

- In the Eye of the Hurricane (José María Forqué, 1971; Italian: La volpe dalla coda di velluto / The Fox with the Velvet Tail)

- The Glass Ceiling (Eloy de la Iglesia, 1971; Spanish: El techo de cristal) stars Patty Shepard and Emma Cohen

- Two Males for Alexa (Juan Logar, 1971; Spanish: Fieras sin jaula / Cageless Beasts) aka Due maschi per Alexa; stars Rosalba Neri and Emma Cohen

- The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave (Emilio Miraglia, 1971; Italian: La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba)

- Amuck! (Silvio Amadio, 1972; Italian: Alla ricerca del piacere / In Pursuit of Pleasure) a.k.a.Maniac Mansion, a.k.a.Leather and Whips, a.k.a.Hot Bed of Sex

- The Red Headed Corpse (Renzo Russo, 1972; Italian: La rossa dalla pelle che scotta) a.k.a.The Sensuous Doll

- The Case of the Bloody Iris (Giuliano Carnimeo, 1972; Italian: Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? / What Are Those Strange Drops of Blood on Jennifer's Body?)

- Don't Torture a Duckling (Lucio Fulci, 1972; Italian: Non si sevizia un paperino) a.k.a.The Long Night of Exorcism

- Who Killed the Prosecutor and Why? (Giuseppe Vari, 1972; Italian: Terza ipotesi su un caso di perfetta strategia criminale / Third hypothesis about a perfect criminal strategy case)

- Death Walks at Midnight (Luciano Ercoli, 1972: Italian: La morte accarezza a mezzanotte/ Death Caresses at Midnight) a.k.a.Cry Out in Terror

- An Open Tomb...An Empty Coffin (Alfonso Balcázar, 1972; Spanish: La casa de las muertas vivientes / House of the Living Dead Women) aka The Nights of the Scorpion

- Who Saw Her Die? (Aldo Lado, 1972; Italian: Chi l'ha vista morire?)

- My Dear Killer (Tonino Valerii, 1972; Italian: Mio caro assassino)

- A White Dress for Marialé (Romano Scavolini, 1972; Italian: Un bianco vestito per Marialé) a.k.a.Spirits of Death

- Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (Sergio Martino, 1972; Italian: Il tuo vizio è una stanza chiusa e solo io ne ho la chiave) a.k.a.Gently Before She Dies, a.k.a.Eye of the Black Cat, a.k.a.Excite Me!

- The French Sex Murders (Ferdinando Merighi, 1972; Italian: Casa d'appuntamento/ The House of Rendezvous) a.k.a.The Bogey Man and the French Murders

- Death Falls Lightly (Leopoldo Savona, 1972; Italian: La morte scende leggera)[57]

- Smile Before Death (Silvio Amadio, 1972; Italian: Il sorriso della iena) a.k.a.Smile of the Hyena

- What Have You Done to Solange? (Massimo Dallamano, 1972; Italian: Cosa avete fatto a Solange?) a.k.a.Secret of the Green Pins, a.k.a.Who's Next?, a.k.a.Terror in the Woods

- Knife of Ice (Umberto Lenzi, 1972; Italian: Il coltello di ghiaccio)

- Eye in the Labyrinth (Mario Caiano, 1972; Italian: L'occhio nel labirinto)

- Murder Mansion (Francisco Lara Polop, 1972; Italian: Quando Marta urlò dalla tomba / When Marta Screamed from the Grave) a.k.a.The House in the Fog

- All the Colors of the Dark (Sergio Martino, 1972; Italian: Tutti i colori del buio) a.k.a.Day of the Maniac, a.k.a.They're Coming to Get You!

- The Killer Is on the Phone (Alberto De Martino, 1972; Italian: L'assassino e' al telefono) a.k.a.Scenes From a Murder

- Tropic of Cancer (Edoardo Mulargia, 1972; Italian: Al Tropico del Cancro) a.k.a.Death in Haiti

- Amore e morte nel giardino degli dei (Sauro Scavolini, 1972; English: Love and Death in the Garden of the Gods)

- The Dead Are Alive (Armando Crispino, 1972; Italian: L'etrusco uccide ancora / The Etruscan Kills Again)

- So Sweet, So Dead (Roberto Montero, 1972; Italian: Rivelazione di un maniaco sessuale) a.k.a.The Slasher is the Sex Maniac, a.k.a.Penetration

- Delirium (Renato Polselli, 1972; Italian: Delirio caldo)

- Seven Blood-Stained Orchids (Umberto Lenzi, 1972; Italian: Sette orchidee macchiate di rosso)

- The Crimes of the Black Cat (Sergio Pastore, 1972; Italian: Sette scialli di seta gialla / Seven Shawls of Yellow Silk)

- Naked Girl Killed in the Park (Alfonso Brescia, 1972; Italian: Ragazza tutta nuda assassinata nel parco) a.k.a.Naked Girl Found in the Park

- The Two Faces of Fear (Tulio Demicheli, 1972; Italian: I due volti della paura)

- The Weapon, the Hour, the Motive (Francesco Mazzei, 1972; Italian: L'arma, l'ora, il movente)

- The Red Queen Kills Seven Times (Emilio Miraglia, 1972; Italian: La dama rossa uccide sette volte) a.k.a.Blood Feast, a.k.a.Feast of Flesh

- Death Carries a Cane (Maurizio Pradeaux, 1973) Italian: Passi di danza su una lama di rasoio / Dance Steps on a Razor's Edge; a.k.a.Maniac at Large, a.k.a.Tormentor

- Torso (Sergio Martino, 1973; Italian: I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale / The Bodies Show Traces of Carnal Violence)

- The Flower with the Petals of Steel (Gianfranco Piccioli, 1973; Italian: Il fiore dai petali d'acciaio / The Flower with the Deadly Sting)

- Seven Deaths in the Cat's Eye (Antonio Margheriti, 1973; Italian: La morte negli occhi del gatto / Death in the Eyes of the Cat)https://news.knowledia.com/GB/en/topics/199Tq* The Bloodstained Lawn (Riccardo Ghione, 1973; Italian: Il prato macchiato di rosso)

- Love and Death on the Edge of a Razor (Giusseppe Pellegrini, 1973; Italian: Giorni d'amore sul filo di una lama) a.k.a.Muerte au Rasoir

- Nadie oyó gritar (Eloy de la Iglesia, 1973; Spanish[58]) translation: No One Heard the Scream)

- The Crimes of Petiot (José Luis Madrid, 1973; Spanish: Los crímenes de Petiot)

- Death Smiles on a Murderer (Joe D'Amato, 1973; Italian: La morte ha sorriso all'assassino)

- Don't Look Now (Nicolas Roeg, 1973; Italian: A Venezia... un Dicembre rosso shocking / In Venice... a Shocking Red December)[59]

- The Perfume of the Lady in Black (Francesco Barilli, 1974; Italian: Il profumo della signora in nero)

- Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll (Carlos Aured, 1974; Spanish: Los ojos azules de la muñeca rota) a.k.a.House of Psychotic Women

- Five Women for the Killer (Stelvio Massi, 1974; Italian: Cinque donne per l'assassino)

- Spasmo (Umberto Lenzi, 1974)

- Puzzle (Duccio Tessari, 1974; Italian: L'uomo senza memoria / The Man Without a Memory)

- The Girl in Room 2A (William Rose, 1974, Italian: La casa della paura / The House of Fear) a.k.a.The Perversions of Mrs. Grant

- The Killer Reserved Nine Seats (Giuseppe Bennati, 1974; Italian: L'assassino ha riservato nove poltrone)

- What Have They Done to Your Daughters? (Massimo Dallamano, 1974; Italian: La polizia chiede aiuto / The Police Need Help) a.k.a.The Co-ed Murders

- Ciak...si muore (Mario Moroni, 1974; rough translation: Clack...You Die (as in the sound a clapboard makes))

- The Killer Is One of the Thirteen (Javier Aguirre, 1974; Spanish: El asesino está entre los trece)

- The Killer Wore Gloves (Juan Bosch, 1974; Spanish: La Muerte llama a las diez / Death Calls at Ten) a.k.a.Le calde labbra del carnefice / The Hot Lips of the Killer

- The Killer With a Thousand Eyes (Juan Bosch, 1974; Spanish: Los mil ojos del asesino) a.k.a.On The Edge

- The Fish With the Gold Eyes (Pedro Luis Ramírez, 1974, Spanish: El pez del los ojos de oro)

- Death Will Have Your Eyes (Giovanni D'Eramo, 1974; Italian: La moglie giovane)

- Eyeball (Umberto Lenzi, 1975; Italian: Gatti rossi in un labirinto di vetro / Red Cats in a Glass Maze) a.k.a.Wide-Eyed in the Dark

- Autopsy (Armando Crispino, 1975); Italian: Macchie solari / Sunspots

- The Killer Must Kill Again (Luigi Cozzi, 1975; Italian: L'assassino è costretto ad uccidere ancora) a.k.a.Il Ragno (The Spider), a.k.a.The Dark is Death's Friend

- All the Screams of Silence (Ramón Barco, 1975, Spanish: Todo los gritos del silencio)

- A Dragonfly for Each Corpse (León Klimovsky, 1975; Spanish: Una libélula para cada muerto)

- Footprints on the Moon (Luigi Bazzoni, 1975; Italian: Le orme)

- Deep Red (Dario Argento, 1975; Italian: Profondo rosso) a.k.a.The Hatchet Murders [55]

- Strip Nude for Your Killer (Andrea Bianchi, 1975) a.k.a. Nude per l'assassino

- Reflections in Black (Tano Cimarosa, 1975; Italian: Il vizio ha le calze nere / Vice Wears Black Hose)

- The Suspicious Death of a Minor (Sergio Martino, 1975; Italian: Morte sospetta di una minorenne) a.k.a.Too Young to Die

- The Bloodsucker Leads the Dance (Alfredo Rizzo, 1975; Italian: La sanguisuga conduce la danza) a.k.a.The Passion of Evelyn

- ...a tutte le auto della polizia (Mario Caiano, 1975; English: Calling All Police Cars)

- Snapshot of a Crime (Mario Imperoli, 1975; Italian: Istantanea per un delitto)

- The House with Laughing Windows (Pupi Avati, 1976; Italian: La casa dalle finestre che ridono)

- Plot of Fear (Paolo Cavara, 1976; Italian: E tanta paura)

- Death Steps in the Dark (Maurizio Pradeaux, 1977; Italian: Passi di morte perduti nel buio)

- Crazy Desires of a Murderer (Filippo Walter Ratti, 1977; Italian: I vizi morbosi di una governante)

- Sette note in nero (Lucio Fulci, 1977) a.k.a.The Psychic, a.k.a.Murder to the Tune of Seven Black Notes

- The Pyjama Girl Case (Flavio Mogherini, 1977; Italian: La ragazza dal pigiama giallo / The Girl in the Yellow Pyjamas)

- Watch Me When I Kill (Antonio Bido, 1977; Italian: Il gatto dagli occhi di giada / The Cat with the Jade Eyes) a.k.a.The Cat's Victims

- Nine Guests for a Crime (Ferdinando Baldi, 1977; Italian: 9 ospiti per un delitto) a.k.a.A Cry in the Night

- Hotel Fear (Francesco Barilli, 1978; Italian: Pensione Paura)

- The Sister of Ursula (Enzo Milioni, 1978; Italian: La sorella di Ursula) a.k.a.La muerte tiene ojos / Death Has Eyes, a.k.a.Ursula's Sister

- Red Rings of Fear (Alberto Negrin, 1978; Italian: Enigma rosso/ Red Enigma) a.k.a.Virgin Terror, a.k.a.Trauma, a.k.a.Rings of Fear

- The Bloodstained Shadow (Antonio Bido, 1978; Italian: Solamente nero / Only Blackness)

- L'immoralità (Massimo Pirri, 1978) a.k.a. Cock Crows at Eleven

- The Perfect Crime (Giuseppe Rosati, 1978; Italian: Indagine su un delitto perfetto)

- Atrocious Tales of Love and Death (Sergio Corbucci, 1979; Italian: Giallo napoletano) a.k.a. Melodie meurtriere, a.k.a. Atrocious Tales of Love and Revenge[60]

- Killer Nun (Giulio Berutti, 1979; Italian: Suir omicidi) a.k.a.Deadly Habit

- Giallo a Venezia (Mario Landi, 1979) a.k.a.Giallo in Venice, a.k.a.Giallo, Venetian Style

1980s

- Trhauma (Gianni Martucci, 1980; Italian: Il mistero della casa maledetta / Mystery of the Cursed House) a.k.a.Trauma

- Murder Obsession (Riccardo Freda, 1981; Italian: Follia omicida / Murder Madness[61]) a.k.a.Fear, a.k.a.The Wailing, a.k.a.The Murder Syndrome

- The Secret of Seagull Island (Nestore Ungaro, 1981; Italian: L'isola del gabbiano) feature version edited from a 1981 multi-part TV series called Seagull Island; a British/Italian co-production

- Madhouse (Ovidio Assonitis, 1981) a.k.a. There Was a Little Girl, a.k.a. And When She Was Bad

- Nightmare (Romano Scavolini, 1981) a.k.a.Nightmares in a Damaged Brain

- Tenebrae (Dario Argento, 1982) a.k.a.Unsane [55]

- The Scorpion with Two Tails (Sergio Martino, 1982; Italian: Assassinio al cimitero etrusco / Murder in the Etruscan Cemetery)

- The New York Ripper (Lucio Fulci, 1982; Italian: Lo squartatore di New York)

- Killing of the Flesh (Cesare Canaveri, 1982; English: Delitto Carnale/ Carnal Crime) a.k.a. Sensual Murder

- A Blade in the Dark (Lamberto Bava, 1983; Italian: La casa con la scala nel buio / The House with the Dark Staircase)

- Extrasensorial (Alberto De Martino, 1983) a.k.a. Blood Link

- Dagger Eyes (Carlo Vanzina, 1983) a.k.a. Mystère, a.k.a. Murder Near Perfect

- The House of the Yellow Carpet (Carlo Lizzani, 1983; Italian: La casa del tappeto giallo)

- Murder Rock (Lucio Fulci, 1984; Italian: Murderock – uccide a passo di danza) a.k.a.The Demon Is Loose!, a.k.a.Murder Rock – Dancing Death

- Nothing Underneath (Carlo Vanzina, 1985; Italian: Sotto il vestito niente) a.k.a.The Last Shot

- Formula for a Murder (Alberto De Martino, 1985) a.k.a.7 Hyden Park – La casa maledetta/ 7 Hyde Park - The Cursed House)

- Phenomena (Dario Argento, 1985) a.k.a.Creepers

- The House of the Blue Shadows (Beppe Cino, 1986; Italian: La casa del buon ritorno) a.k.a. The House with the Blue Shutters

- The Killer is Still Among Us (Camillo Teti, 1986; Italian: L'assassino è ancora tra noi)

- Delitti (Giovanna Lenzi, 1986; English: Crimes)

- You'll Die at Midnight (Lamberto Bava, 1986; Italian: Morirai a mezzanotte) a.k.a.The Midnight Killer, a.k.a. Midnight Horror

- The Monster of Florence (Cesare Ferrario, 1986; Italian: Il mostro di firenze) a.k.a. Night Ripper

- Sweets from a Stranger (Franco Ferrini, 1987; Italian: Caramelle da uno sconosciuto)

- Phantom of Death (Ruggero Deodato, 1987; Italian: Un delitto poco comune / An Uncommon Crime) a.k.a.Off Balance

- Stage Fright (Michele Soavi, 1987; Italian: Deliria) a.k.a.Aquarius, a.k.a.Bloody Bird

- Delirium (Lamberto Bava, 1987; Italian: Le foto di Gioia / Photos of Gioia)

- Body Count (Ruggero Deodato, 1987) a.k.a. Camping del terrore, a.k.a. The Eleventh Commandment

- Too Beautiful to Die (Dario di Piana, 1988; Italian: Sotto il vestito niente 2 / Nothing Underneath 2)

- Dial: Help (Ruggero Deodato, 1988; Italian: Minaccia d'amore / Love Threat)

- Delitti e profumi (Vittorio De Sisti, 1988; English: Crimes and Perfume)

- Obsession: A Taste for Fear (Piccio Raffanini, 1988; Italian: Pathos: Un sapore di paura)

- Opera (Dario Argento, 1988) a.k.a.Terror at the Opera [55]

- The Murder Secret (Mario Bianchi, Lucio Fulci, 1988; Italian: Non aver paura della zia Marta / Don't Be Afraid of Aunt Martha) a.k.a.Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things

- Massacre (Andrea Bianchi, 1989)

- Nightmare Beach (Umberto Lenzi, 1989) a.k.a.Welcome To Spring Break

- Arabella, the Black Angel (Stelvio Massi, 1989) a.k.a.Black Angel

1990s

- Homicide in Blue Light (Alfonso Brescia, 1991; Italian: Omicidio a luci blu)

- Trauma (Dario Argento, 1992) a.k.a.Dario Argento's Trauma

- Misteria (Lamberto Bava, 1992) a.k.a.Body Puzzle

- Circle of Fear (Aldo Lado, 1992) a.k.a.The Perfect Alibi

- Madness (1992 film) (Bruno Mattei, 1994; Italian; Gli occhi dentro) aka Occhi Senza Volto/Eyes Without a Face

- The Washing Machine (Ruggero Deodato, 1993; Italian: Vortice Mortale)

- Dangerous Attraction (Bruno Mattei, 1993) starring David Warbeck

- Omicidio al Telefono (Bruno Mattei, 1994) aka L'assassino e al telefono[62]

- The Strange Story of Olga O (Antonio Bonifacio, 1995) written by Ernesto Gastaldi

- The Stendhal Syndrome (Dario Argento, 1996; Italian: La sindrome di Stendhal)

- The House Where Corinne Lived (Maurizio Lucidi, 1996; Italian: La casa dove abitava Corinne)

- Fatal Frames (Al Festa, 1996)

- The Wax Mask (Sergio Stivaletti, 1997; Italian: M.D.C. – Maschera di cera)

- Milonga (Emidio Greco, 1999)

2000 to present

- Sleepless (Dario Argento, 2001; Italian: Non ho sonno)

- Bad Inclination (Pierfrancesco Campanella, 2003: Italian: Cattive inclinazioni)

- The Card Player (Dario Argento, 2004; Italian: Il cartaio)

- Eyes of Crystal (Eros Puglielli, 2004; Italian: Occhi di cristallo)

- The Vanity Serum (Alex Infascelli, 2004; Italian: Il siero della vanità)

- Do You Like Hitchcock? (Dario Argento, 2005; Italian: Ti piace Hitchcock?)

- Giallo (Dario Argento, 2009)

- Symphony in Blood Red (Luigi Pastore, 2010)

- Sonno Profondo (Luciano Onetti, 2013)

Notable personalities

Directors

- Silvio Amadio

- Dario Argento

- Francesco Barilli

- Lamberto Bava

- Mario Bava

- Luigi Bazzoni

- Giuliano Carnimeo

- Paolo Cavara

- Armando Crispino

- Massimo Dallamano

- Alberto De Martino

- Ruggero Deodato

- Luciano Ercoli

- Riccardo Freda

- Lucio Fulci

- Romolo Guerrieri

- Aldo Lado

- Umberto Lenzi

- Antonio Margheriti

- Sergio Martino

- Emilio Miraglia

- Duccio Tessari

Writers

Actors

- Simón Andreu

- Claudine Auger

- Ewa Aulin

- Barbara Bach

- Carroll Baker

- Eva Bartók

- Agostina Belli

- Femi Benussi

- Helmut Berger

- Erika Blanc

- Florinda Bolkan

- Barbara Bouchet

- Pier Paolo Capponi

- Adolfo Celi

- Anita Ekberg

- Rossella Falk

- Mimsy Farmer

- Edwige Fenech

- James Franciscus

- Cristina Galbó

- Ida Galli

- Giancarlo Giannini

- Farley Granger

- Brett Halsey

- David Hemmings

- George Hilton

- Robert Hoffmann

- Suzy Kendall

- Sylva Koscina

- Dagmar Lassander

- Philippe Leroy

- Beba Lončar

- Ray Lovelock

- Marina Malfatti

- Leonard Mann

- Marisa Mell

- Luc Merenda

- Macha Meril

- Tomas Milian

- Cameron Mitchell

- Silvia Monti

- Tony Musante

- Paul Naschy

- Nieves Navarro

- Rosalba Neri

- Franco Nero

- Daria Nicolodi

- Luciana Paluzzi

- Irene Papas

- Luigi Pistilli

- Ivan Rassimov

- Fernando Rey

- John Richardson

- George Rigaud

- Letícia Román

- Howard Ross

- John Saxon

- Erna Schürer

- Jean Sorel

- Anthony Steffen

- John Steiner

- Anita Strindberg

- Fabio Testi

- Gabriele Tinti

- Marilu Tolo

Films influenced by giallo

- Klute (1971) [45]

- Frenzy (1972)[64]

- Sisters (1973)[43]

- Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)[65]

- Halloween (1978)[43]

- Cruising (1980)[45]

- Friday the 13th (1980)[43]

- Dressed to Kill (1980)[45]

- Body Double (1984)[45]

- Basic Instinct (1992)[45]

- The Rebel Lady With The Dark Secrets (French, 2018) [66]

See also

- Arthouse action film

- Detective fiction

- Erotic thriller

- Exploitation fiction

- Exploitation film

- Fantastique

- Grand Guignol

- Murder mystery

- Mystery fiction

- Mystery film

- New Hollywood

- Poliziotteschi

- Psychedelic film

- Psychological horror

- Psychological thriller

- Pulp magazine

- Slasher film

- Splatter film

- Vulgar auteurism

- Weird menace

- Whodunit

References

- Simpson, Clare (February 4, 2013). "Watch Me While I Kill: Top 20 Italian Giallo Films". WhatCulture. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17.

- Needham, Gary. "Playing with Genre: An Introduction to the Italian Giallo". Kinoeye. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Kerswell 2012, pp. 46–49.

- da Conceição, Ricky (October 16, 2012). "Greatest (Italian) Giallo Films". Sound on Sight. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- Hudson, Kelly. "All the Colors of Giallo: Blood, Sex, the Occult, and Heaping Loads of 70's Weirdness". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Nashawaty, Chris (Jul 18, 2019). "Murder, Italian Style: A Primer on the Giallo Film Genre". Vulture. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- "Gateways To Geekery: Giallo". Film. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Vago, Mike. "Alongside spaghetti Westerns, Italy was also making "spaghetti thrillers" in the '60s". AV Club. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Koven, Mikel (October 2, 2006). La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press. p. 66. ISBN 0810858703.

- Anne Billson (October 14, 2013). "Violence, mystery and magic: how to spot a giallo movie". The Tekegraph. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- Kyle Anderson (2 January 2019). "Giallo is the horror subgenre you need to explore". Nerdist. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Pinkerton, Nick (4 July 2014). "Bombast: Poliziotteschi and Screening History". Film Comment. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "10 Giallo Films for Beginners". Film School Rejects. Oct 13, 2018. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Abrams, Jon (16 March 2015). "GIALLO WEEK! YOUR INTRODUCTION TO GIALLO FEVER!". The Daily Grindhouse. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Koven, Mikel (October 2, 2006). La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press. p. 4. ISBN 0810858703.

- "Of Giallo and Gore: A Review | Unwinnable". unwinnable.com. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Kannas, Alexia (August 2006). "Simple Acts of Annihilation: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film by Mikel J. Koven". Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Guins, Ray (1996). "Tortured Looks: Dario Argento and Visual Displeasure". Necronomicon: The Journal of Horror and Erotic Cinema. Creation Books. 1: 141–153.

- Koven, Mikel (October 2, 2006). La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press. p. 147. ISBN 0810858703.

- Murray, Noel (October 20, 2011). "Gateways to Geekery: Giallo". The A.V. Club. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Hunt, Leon (Autumn 1992). "A (Sadistic) Night at the Opera: Notes on the Italian Horror Film". Velvet Light Trap. 30: 74.

- Koven, Mikel (October 2, 2006). La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press. p. 3. ISBN 0810858703.

- Olney, Ian (February 7, 2013). Euro Horror: Classic European Horror Cinema in Contemporary American Culture (New Directions in National Cinemas). Indiana University Press. pp. 36, 104, 117. ISBN 025300652X.

- Koven, Mikel (October 2, 2006). La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press. p. 16. ISBN 0810858703.

- McDonagh, Maitland (March 22, 2010). Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento. University of Minnesota Press. p. vii. ISBN 081665607X.

- "Giallo Cinema: Spaghetti Slashers - The Grindhouse Cinema Database". www.grindhousedatabase.com. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Giovannini, Fabio (1986). Dario Argento: il brivido, il sangue, il thrilling. Edizione Dedalo. pp. 27–28. ISBN 8822045165.

- Jr, Phil Nobile (Oct 11, 2015). "A Genre Between Genres: The Shadow World Of German Krimi Films". Birth.Movies.Death. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Andersson, Pidde (October 2, 2006). Blue Swede Shock! The History of Swedish Horror Films. The TOPPRAFFEL! Library. ISBN 1445243040.

- Alanen, Antti. "Mannekäng i rött / Mannequin in Red (SFI 2000 restoration)". Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Lucas 2013, p. 566.

- MacKenzie, Michael (Director) (2015). Gender and Giallo (Documentary). Arrow Films.

- Rockoff, Adam (2002). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978-1986. McFarland. p. 30. ISBN 0786469323.

- Lucas, Tim. Blood and Black Lace DVD, Image Entertainment, 2005, liner notes. ASIN: B000BB1926

- McDonagh, Maitland (March 22, 2010). Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento. University of Minnesota Press. p. 14. ISBN 081665607X.

- Soavi, Michele (1996). "Michele Soavi Interview". In Palmerini, Luca M.; Mistretta, Gaetano (eds.). Spaghetti Nightmares. Fantasma Books. p. 147. ISBN 0963498274.

- Zadeh, Hossein Eidi. "15 Essential Films For An Introduction to Italian Giallo Movies". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Rockoff, Adam (2002). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978-1986. McFarland. pp. 38–43. ISBN 0786469323.

- Hanke, Ken (2003), "The Lost Horror Film Series: The Edgar Wallace Kirmis.", in Schnieder, Steven Jay (ed.), In Fear without Frontiers: Horror Cinema across the Globe, Godalming, UK: FAB Press, pp. 111–123

- Kerswell 2012, pp. 54–55.

- "Tutti. Defunti. Tranne. I. Morti. zo". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "Jane Fonda's 'Klute' Belongs in the 1970s Hollywood Canon". Film School Rejects. Aug 28, 2015. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Hesom, Dean. "15 Great Thrillers That Were Influenced By Italian Giallo Films". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- "Brian De Palma Week: How Dressed to Kill blends Hitchcock and Giallo". Cinema76. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Hesom, Dean. "15 Great Thrillers That Were Influenced By Italian Giallo Films". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- "Film of the week: Berberian Sound Studio". British Film Institute. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Oyarzun, Hector. "20 Movies With The Most Brilliant Sound Design". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Roth, Eli (October 10, 2014). Watch: Eli Roth Talks Giallo-Inspired 'House with the Laughing Windows' (Video Short). Thompson on Hollywood. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Roth, Eli (November 1, 2007). "Eli Roth Presents The Best Horror Movies You've Never Seen". Rotten Tomatoes (Interview). Interviewed by Joe Utichi.

- Luther-Smith, Adrian (1999). Blood and Black Lace: The Definitive Guide to Italian Sex and Horror Movies. Stray Cat Publishing Ltd. p. 30

- Simone Petricci. Il Cinema E Siena: La Storia, I Protagonisti, Le Opere. Manent, 1997.

- "The House That Screamed (1970) - Narciso Ibañez Serrador | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related | AllMovie". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020 – via www.allmovie.com.

- Binion, Cavett. "The House That Screamed". Allmovie. Macrovision. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- Luca Rea. I colori del buio: il cinema thrilling italiano dal 1930 al 1979. I. Molino, 1999.

- Worland, Rick (2006). The Horror Film: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 276. ISBN 1405139013.

- Luther-Smith,Adrian (1999). Blood and Black Lace: The Definitive Guide to Italian Sex and Horror Movies. Stray Cat Publishing Ltd. p. 43

- Luther-Smith, Adrian (1999). Blood and Black Lace: The Definitive Guide to Italian Sex and Horror Movies. Stray Cat Publishing Ltd. p.70

- "Nadie Oyó Gritar - Knowledia News". news.knowledia.com. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Stanley, Anya (October 4, 2019). "The Diffusion of Giallo in Nicolas Roeg's 'Don't Look Now'". Vague Visages.

- Luther-Smith, Adrian (1999). Blood and Black Lace: The Definitive Guide to Italian Sex and Horror Movies. Stray Cat Publishing Ltd. p. 3

- Curti, Roberto (2017). Riccardo Freda: The Life and Works of a Born Filmmaker. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476628387.

- Lupi, Gordiano; Gazzarrini, Ivo (2013). Bruno Mattei: L'ultimo artigiano. ISBN 9788876064609.

- "Where to begin with giallo". British Film Institute. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- Fischer, Russ (Oct 26, 2015). "Black Gloves And Knives: 12 Essential Italian Giallo". Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- "Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)". Giallo Reviews. Retrieved Dec 27, 2020.

- "The Rebel Lady With The Dark Secrets - Review". nevermore-horror.com. Retrieved September 10, 2020.