Voyeurism

Voyeurism is the sexual interest in or practice of watching other people engaged in intimate behaviors, such as undressing, sexual activity, or other actions usually considered to be of a private nature.[1]

| Voyeurism | |

|---|---|

| |

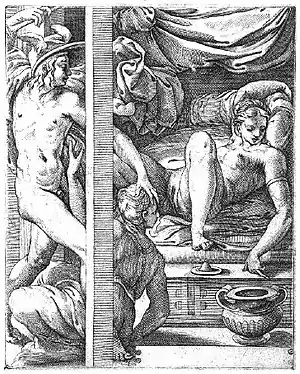

| "Mercury and Herse", scene from The Loves of the Gods by Gian Giacomo Caraglio, showing Mercury, Herse, and Aglaulos | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

The term comes from the French voir which means "to see". A male voyeur is commonly labelled as "Peeping Tom" or a "Jags", a term which originates from the Lady Godiva legend.[2] However, that term is usually applied to a male who observes somebody secretly and, generally, not in a public space.

The American Psychiatric Association has classified certain voyeuristic fantasies, urges and behaviour patterns as a paraphilia in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) if the person has acted on these urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.[3] It is described as a disorder of sexual preference in the ICD-10.[4] The DSM-IV defines voyeurism as the act of looking at "unsuspecting individuals, usually strangers, who are naked, in the process of disrobing, or engaging in sexual activity".[5] The diagnosis would not be given to people who experience typical sexual arousal simply by seeing nudity or sexual activity. In order to be diagnosed with voyeuristic disorder the symptoms must persist for over six months and the person in question must be over the age of 18.[6]

Historical perspectives

There is relatively little academic research regarding voyeurism. When a review was published in 1976 there were only 15 available resources.[7] Voyeurs were well-paying hole-lookers in especially Parisian brothels, a commercial innovation described as far back as 1857 but not gaining much notoriety until the 1880s, and not attracting formal medical-forensic recognition until the early 1890s.[8] Society has accepted the use of the term voyeur as a description of anyone who views the intimate lives of others, even outside of a sexual context.[9] This term is specifically used regarding reality television and other media which allow people to view the personal lives of others. This is a reversal from the historical perspective, moving from a term which describes a specific population in detail, to one which describes the general population vaguely.

One of the few historical theories on the causes of voyeurism comes from psychoanalytic theory. Psychoanalytic theory proposes that voyeurism results from a failure to accept castration anxiety and as a result a failure to identify with the father.[5]

Prevalence

Voyeurism has high prevalence rates in most studied populations. Voyeurism was initially believed to only be present in a small portion of the population. This perception changed when Alfred Kinsey discovered that 30% of men prefer coitus with the lights on.[5] This behaviour is not considered voyeurism by today's diagnostic standards, but there was little differentiation between normal and pathological behaviour at the time. Subsequent research showed that 65% of men had engaged in peeping, which suggests that this behaviour is widely spread throughout the population.[5] Congruent with this, research found voyeurism to be the most common sexual law-breaking behaviour in both clinical and general populations.[10] In the same study it was found that 42% of college males who had never been convicted of a crime had watched others in sexual situations. An earlier study indicates that 54% of men have voyeuristic fantasies, and that 42% have tried voyeurism.[11] In a national study of Sweden it was found that 7.7% of the population (both men and women) had engaged in voyeurism at some point.[12] It is also believed that voyeurism occurs up to 150 times more frequently than police reports indicate.[12] This same study also indicates that there are high levels of co-occurrence between voyeurism and exhibitionism, finding that 63% of voyeurs also report exhibitionist behaviour.[12]

Characteristics

Due to the prevalence of voyeurism in society, the people who engage in voyeuristic behaviours are diverse. However, there are some trends regarding who is likely to engage in voyeurism. These statistics apply only to those who qualify as voyeurs under the definition of the DSM, and not the broader modern concept of voyeurism as discussed earlier in this article.

Early research indicated that voyeurs were more mentally healthy than other groups with paraphilias.[7] Compared to the other groups studied, it was found that voyeurs were unlikely to be alcoholics or drug users. More recent research shows that, compared to the general population, voyeurs were moderately more likely to have psychological problems, use alcohol and drugs, and have higher sexual interest generally.[12] This study also shows that voyeurs have a greater number of sexual partners per year, and are more likely to have had a same-sex partner than general populations.[12] Both older and newer research found that voyeurs typically have a later age of first sexual intercourse.[7][12] However, other research found no difference in sexual history between voyeurs and non-voyeurs.[11] Voyeurs who are not also exhibitionists tend to be from a higher socioeconomic status than those who do show exhibitionist behaviour.[12]

Research shows that, like almost all paraphilias, voyeurism is more common in men than in women.[12] However, research has found that men and women both report roughly the same likelihood that they would hypothetically engage in voyeurism.[13] There appears to be a greater gender difference when actually presented with the opportunity to perform voyeurism. There is very little research done on voyeurism in women, so very little is known on the subject. One of the few studies deals with a case study of a woman who also had schizophrenia. This limits the degree to which it can generalise to normal populations.[14]

Current perspectives

Lovemap theory suggests that voyeurism exists because looking at naked others shifts from an ancillary sexual behaviour, to a primary sexual act.[13] This results in a displacement of sexual desire making the act of watching someone the primary means of sexual satisfaction.

Voyeurism has also been linked with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). When treated by the same approach as OCD, voyeuristic behaviours significantly decrease.[15]

Treatment

Professional treatment

Historically voyeurism has been treated in a variety of ways. Psychoanalytic, group psychotherapy and shock aversion approaches have all been attempted with limited success.[7] There is some evidence that shows that pornography can be used as a form of treatment for voyeurism. This is based on the idea that countries with pornography censorship have high amounts of voyeurism.[16] Additionally shifting voyeurs from voyeuristic behaviour, to looking at graphic pornography, to looking at the nudes in Playboy has been successfully used as a treatment.[17] These studies show that pornography can be used as a means of satisfying voyeuristic desires without breaking the law.

Voyeurism has also been successfully treated with a mix of anti-psychotics and antidepressants. However the patient in this case study had a multitude of other mental health problems. Intense pharmaceutical treatment may not be required for most voyeurs.[18]

There has also been success in treating voyeurism through using treatment methods for obsessive compulsive disorder. There have been multiple instances of successful treatment of voyeurism through putting patients on fluoxetine and treating their voyeuristic behaviour as a compulsion.[9][15]

Techniques

The increased miniaturisation of hidden cameras and recording devices since the 1950s has enabled those so minded to surreptitiously photograph or record others without their knowledge and consent. The vast majority of mobile phones, for example, are readily available to be used for their camera and recording ability.

Certain devices are capable of producing “see through” images of a person through materials that are opaque to visible light, such as clothing. These devices form images by using electromagnetic radiation outside the visible range. Infrared and terahertz-wave cameras are capable of creating images through clothing, though these images differ from what would be created with visible light.[19][20]

Criminology

Non-consensual voyeurism is considered to be a form of sexual abuse.[21][22][23] When the interest in a particular subject is obsessive, the behaviour may be described as stalking.

The United States FBI assert that some individuals who engage in "nuisance" offences (such as voyeurism) may also have a propensity for violence based on behaviours of serious sex offenders.[24] An FBI researcher has suggested that voyeurs are likely to demonstrate some characteristics that are common, but not universal, among serious sexual offenders who invest considerable time and effort in the capturing of a victim (or image of a victim); careful, methodical planning devoted to the selection and preparation of equipment; and often meticulous attention to detail.[25]

Little to no research has been done into the demographics of voyeurs.

Legal status

Voyeurism is not a crime at common law. In common law countries it is only a crime if made so by legislation. In Canada, for example, voyeurism was not a crime when the case Frey v. Fedoruk et al. arose in 1947. In that case, in 1950, the Supreme Court of Canada held that courts could not criminalise voyeurism by classifying it as a breach of the peace and that Parliament would have to specifically outlaw it. On November 1, 2005, this was done when section 162 was added to the Canadian Criminal Code, declaring voyeurism to be a sexual offence.[26]

In some countries voyeurism is considered to be a sex crime. In the United Kingdom, for example, non-consensual voyeurism became a criminal offence on May 1, 2004.[27] In the English case of R v Turner (2006),[28] the manager of a sports centre filmed four women taking showers. There was no indication that the footage had been shown to anyone else or distributed in any way. The defendant pleaded guilty. The Court of Appeal confirmed a sentence of nine months' imprisonment to reflect the seriousness of the abuse of trust and the traumatic effect on the victims.

In another English case in 2009, R v Wilkins (2010),[29][30] a man who filmed his intercourse with five of his lovers for his own private viewing was sentenced to eight months in prison and ordered to sign onto the Sex Offender Register for ten years. In 2013, 40-year-old Mark Lancaster was found guilty of voyeurism and jailed for 16 months, after he tricked an 18-year-old student into traveling to a rented flat in Milton Keynes, where he filmed her with four secret cameras dressing up as a schoolgirl and posing for photographs before he had sex with her.[31]

In a more recent English case in 2020, the Court of Appeal upheld the conviction of Tony Richards after Richards sought "to have two voyeurism charges under section 67 of the Sexual Offences Act dismissed on the grounds that he had committed no crime".[32][33] Richards "secretly videoed himself having sex with two women who had consented to sex in return for money but had not agreed to being captured on camera".[34] In an unusual step, the court allowed Emily Hunt, a person not involved in the case, to intervene on behalf of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS). Hunt had an ongoing judicial review against the CPS since the CPS had argued that Hunt's alleged attacker had not violated the law when he "took a video lasting over one minute of her naked and unconscious" in a hotel room on the basis that there should be no expectation of privacy in the bedroom. However, in terms of what is considered a private act for the purposes of voyeurism, the CPS was arguing the opposite in the Richards appeal.[33][34] The Court of Appeal clarified that consenting to sex in a private place does not amount to consent to be filmed without that person's knowledge. Anyone who films or photographs another person naked, without their permission, is breaking the law under sections 67 and 68 of the Sexual Offences Act.[32][35]

In the United States, video voyeurism is an offense in twelve states[36] and may require the convicted person to register as a sex offender.[37] The original case that led to the criminalisation of voyeurism has been made into a television movie called Video Voyeur and documents the criminalisation of secret photography. Criminal voyeurism statutes are related to invasion of privacy laws[38] but are specific to unlawful surreptitious surveillance without consent and unlawful recordings including the broadcast, dissemination, publication, or selling of recordings involving places and times when a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy and a reasonable supposition they are not being photographed or filmed by "any mechanical, digital or electronic viewing device, camera or any other instrument capable of recording, storing or transmitting visual images that can be utilised to observe a person."[39]

Saudi Arabia banned the sale of camera phones nationwide in April 2004, but reversed the ban in December 2004. Some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, require all camera phones sold in their country to make a clearly audible sound whenever a picture is being taken.

In 2013, the Indian Parliament made amendments to the Indian Penal Code, introducing voyeurism as a criminal offence.[40] A man committing the offence of voyeurism would be liable for imprisonment not less than one year and which may extend up to three years for the first offence, and shall also be liable to fine and for any subsequent conviction would be liable for imprisonment for not less than three years and which may extend up to seven years and with fine.

Voyeurism is generally deemed illegal in Singapore. It sentences technologically-enabled voyeurs to a maximum punishment of one year's jail and a fine under the context of insulting a woman's modesty.[41]

Secret photography by law enforcement authorities is called surveillance and is not considered to be voyeurism, though it may be unlawful or regulated in some countries.

Popular culture

.jpg.webp)

Films

- Voyeurism is a main theme in films such as The Secret Cinema (1968), Peepers (2010), and Sliver (1993), based on a book of the same name by Ira Levin.

- Voyeurism is a common plot device in both:

- Serious films, e.g., Rear Window (1954), Klute (1971), Blue Velvet (1986), and Disturbia (2007) and

- Humorous films, e.g., Animal House (1978), Gregory's Girl (1981), Porky's (1981), American Pie (1999), and Semi-Pro (2008)

- Voyeuristic photography has been a central element of the mis-en-scene of films such as:

- Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960), and

- Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup (1966)

- Pedro Almodovar's Kika (1993) deals with both sexual and media voyeurism.

- In "Malena" the boy used to spy on a War Widow while she was nude.

- The television movie Video Voyeur: The Susan Wilson Story (2002) is based on a true story about a woman who was secretly videotaped and subsequently helped to get laws against voyeurism passed in parts of the United States.[42]

- Voyeurism is a key plot device in the Japanese movie "Love Exposure (Ai no Mukidashi)". The main Character Yu Honda takes upskirt photos to find his 'Maria' to become a man and get his first taste of sexual stimulation.

Literature

- In the light novel series Baka to Test to Shōkanjū, Kōta Tsuchiya is subject to voyeurism, explaining why he is referred to as "Voyeur".

Manga

- The manga Colourful and Nozoki Ana are both devoted almost entirely to voyeurism.

Music

- "Voyeur", the second track on blink-182's Dude Ranch album, written by Tom DeLonge, features explicit references to the practice of Voyeurism.

- "Sirens", also written by DeLonge, from Angels & Airwaves' album I-Empire is also about voyeurism, albeit in a more subtle way.

Photography

- Merry Alpern with his works, Dirty Windows, 1993-94.[43]

- Kohei Yoshiyuki with his works called The Park.[44]

See also

References

- Hirschfeld, M. (1938). Sexual anomalies and perversions: Physical and psychological development, diagnosis and treatment (new and revised edition). London: Encyclopaedic Press.

- DNB 1890

- "BehaveNet Clinical Capsule: Voyeurism". Behavenet.com. Archived from the original on 2011-11-14. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- "ICD-10". Archived from the original on 2008-09-21. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- Metzl, Jonathan M. (2004). "Voyeur Nation? Changing Definitions of Voyeurism, 1950–2004". Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 12 (2): 127–31. doi:10.1080/10673220490447245. PMID 15204808.

- Staff, PsychCentral. "Voyeuristic Disorder Symptoms". PsychCentral. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- Smith, R. Spencer (1976). "Voyeurism: A review of literature". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 5 (6): 585–608. doi:10.1007/BF01541221. PMID 795401.

- Janssen, D.F. (2018). ""Voyeuristic Disorder": Etymological and Historical Note". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 47 (5): 1307–1311. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1199-2. ISSN 0004-0002. PMID 29582266.

- Metzl, Jonathan (2004). "From scopophilia to Survivor: A brief history of voyeurism". Textual Practice. 18 (3): 415–34. doi:10.1080/09502360410001732935.

- "The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Exhibitionism, Voyeurism, and Frotteurism" (PDF). Niklas Langstrom. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- Templeman, Terrel L.; Stinnett, Ray D. (1991). "Patterns of sexual arousal and history in a ?normal? Sample of young men". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 20 (2): 137–50. doi:10.1007/BF01541940. PMID 2064539.

- Långström, Niklas; Seto, Michael C. (2006). "Exhibitionistic and Voyeuristic Behavior in a Swedish National Population Survey". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 35 (4): 427–35. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9042-6. PMID 16900414.

- Rye, B. J.; Meaney, Glenn J. (2007). "Voyeurism: It Is Good as Long as We Do Not Get Caught". International Journal of Sexual Health. 19: 47–56. doi:10.1300/J514v19n01_06.

- Hurlbert, David (1992). "Voyeurism in an adult female with schizoid personality: A case report". Journal of Sex Education & Therapy. 18: 17–21. doi:10.1080/01614576.1992.11074035.

- Abouesh, Ahmed; Clayton, Anita (1999). "Compulsive voyeurism and exhibitionism: A clinical response to paroxetine". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 28 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1023/A:1018737504537. PMID 10097802.

- Rincover, Arnold (January 13, 1990). "Can Pornography Be Used as Treatment for Voyeurism?". Toronto Star. p. H2.

- Jackson, B (1969). "A case of voyeurism treated by counterconditioning". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 7 (1): 133–4. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(69)90058-8. PMID 5767619.

- Becirovic, E.; Arnautalic, A.; Softic, R.; Avdibegovic, E. (2008). "Case of Successful treatment of voyeurism". European Psychiatry. 23: S200. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.01.317.

- "New security camera can 'see' through clothes". CNN. April 16, 2008.

- Lugmayr, Luigi (Mar 9, 2008). "ThruVision T5000 T-Ray Camera sees through Clothes". I4U.

- "Sexual Violence: Definitions". CDC.gov. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "Child Sexual Abuse Fact Sheet: For Parents, Teachers, and Other Caregivers" (PDF). National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "What Is Child Sexual Abuse?" (PDF). National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Hazelwood, R.R.; Warren, J. (February 1989). "The Serial Rapist: His Characteristics and Victims". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin: 18–25.

- The Criminal Sexual Sadist Archived March 31, 2001, at the Wayback Machine

- Branch, Legislative Services (2019-06-17). "Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Criminal Code". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca.

- Section 67 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003; brought into force by the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (Commencement) Order 2004

- (2006) All ER (D) 95 (Jan)

- (2010) Inner London Crown Court, R v Wilkins.

- "BBC Radio producer jailed over sex tapes". BBC. 4 March 2010.

- Brown, Jonathan; Philby, Charlotte; Milmo, Cahal (2013-07-19). "Computer consultant Mark Lancaster jailed for 16 months for voyeurism and trafficking after using 'sex for fees' website to dupe student into having sex with him". The Independent. London.

- (2020) Court of Appeal, R v Richards.

- Bowcott, Owen (2020-01-28). "Filming partner without their consent during sex ruled a criminal offence". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "Woman who was told man that filmed her naked without consent could not face charges wins fight for justice". The Independent. 2020-01-29. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Savin, Jennifer (2020-03-26). "It's now illegal to take naked pictures of someone without permission". Cosmopolitan. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Norman-Eady, Sandra. "Voyeurism". www.cga.ct.gov.

- Peeping Tom Law & Legal Definition

- "Invasion of Privacy Law & Legal Definition". Definitions.uslegal.com. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- "Stephanie's Law". Criminaljustice.state.ny.us. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- "Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013" (PDF). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Chong, Elena. "Marketing manager jailed 18 weeks for upskirt videos". Straits Times. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Making Video Voyuerism a Crime". CBS News.

- "Juxtapoz Magazine - Merry Alpern's Controversial "Dirty Windows" Series (NSFW)". www.juxtapoz.com. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "The Park de Kohei Yoshiyuki chez Radius Books & Yossi Milo". L'Ascenseur Végétal (in French). Retrieved 2020-05-08.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Voyeurism. |

- UK law on voyeurism

- Proposed US Video Voyeurism Prevention Act of 2003

- Video Voyeurism Laws

- Expert: Technology fosters voyeurism