Flavones

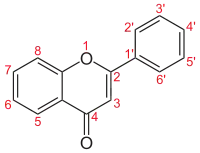

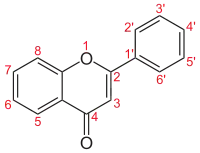

Flavones (from Latin flavus "yellow") are a class of flavonoids based on the backbone of 2-phenylchromen-4-one (2-phenyl-1-benzopyran-4-one) (as shown in the first image of this article).[1][2]

Flavones are common in foods, mainly from spices, and some yellow or orange fruits and vegetables.[1] Common flavones include apigenin (4',5,7-trihydroxyflavone), luteolin (3',4',5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone), tangeritin (4',5,6,7,8-pentamethoxyflavone), chrysin (5,7-dihydroxyflavone), and 6-hydroxyflavone.[1]

Intake and elimination

The estimated daily intake of flavones is about 2 mg per day.[1] Flavones have no proven physiological effects in the human body and no antioxidant food value.[1][3] Following ingestion and metabolism, flavones, other polyphenols, and their metabolites are absorbed poorly in body organs and are rapidly excreted in the urine, indicating mechanisms influencing their presumed absence of metabolic roles in the body.[1][4]

Drug interactions

Flavones have effects on CYP (P450) activity [5][6] which are enzymes that metabolize most drugs in the body.

Organic chemistry

In organic chemistry several methods exist for the synthesis of flavones:

- Allan–Robinson reaction

- Auwers synthesis

- Baker–Venkataraman rearrangement

- Algar–Flynn–Oyamada reaction

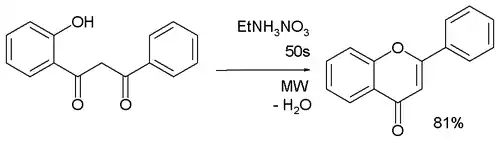

Another method is the dehydrative cyclization of certain 1,3-diaryl diketones.[7]

Wessely–Moser rearrangement

The Wessely–Moser rearrangement (1930)[8] has been an important tool in structure elucidation of flavonoids. It involves the conversion of 5,7,8-trimethoxyflavone into 5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone on hydrolysis of the methoxy groups to phenol groups. It also has synthetic potential for example:[9]

This rearrangement reaction takes place in several steps: A ring opening to the diketone, B bond rotation with formation of a favorable acetylacetone-like phenyl-ketone interaction and C hydrolysis of two methoxy groups and ring closure.

Common flavones

| Name | Structure | R3 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R2' | R3' | R4' | R5' | R6' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavone backbone |  |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Primuletin | – | –OH | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Chrysin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Tectochrysin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Primetin | – | –OH | – | – | –OH | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Apigenin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Acacetin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Genkwanin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Echioidinin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | –OH | – | – | – | – | |

| Baicalein | – | –OH | –OH | –OH | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Oroxylon | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Negletein | – | –OH | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Norwogonin | – | –OH | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Wogonin | – | –OH | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Geraldone | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Tithonine | – | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Luteolin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| 6-Hydroxyluteolin | – | –OH | –OH | –OH | – | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| Chrysoeriol | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Diosmetin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Pilloin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Velutin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Norartocarpetin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Artocarpetin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Scutellarein | – | –OH | –OH | –OH | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Hispidulin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Sorbifolin | – | –OH | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Pectolinarigenin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Cirsimaritin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Mikanin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Isoscutellarein | – | –OH | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Zapotinin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OCH3 | |

| Zapotin | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OCH3 | |

| Cerrosillin | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OCH3 | – | –OCH3 | – | |

| Alnetin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Tricetin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | –OH | –OH | –OH | – | |

| Tricin | – | –OH | – | –OH | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | –OCH3 | – | |

| Corymbosin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | |

| Nepetin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| Pedalitin | – | –OH | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| Nodifloretin | – | –OH | –OH | –OH | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Jaceosidin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Cirsiliol | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| Eupatilin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Cirsilineol | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Eupatorin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | |

| Sinensetin | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | |

| Hypolaetin | – | –OH | – | –OH | –OH | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| Onopordin | – | –OH | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | –OH | –OH | – | – | |

| Wightin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | – | |

| Nevadensin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Xanthomicrol | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | –OH | – | – | |

| Tangeretin | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Serpyllin | – | –OH | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Sudachitin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | –OCH3 | – | –OCH3 | –OH | – | – | |

| Acerosin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | –OCH3 | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Hymenoxin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | –OCH3 | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Gardenin D | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | –OH | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Nobiletin | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | – | – | |

| Scaposin | – | –OH | –OCH3 | –OH | –OCH3 | – | –OCH3 | –OCH3 | –OH | ||

| Name | Structure | R3 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | R2' | R3' | R4' | R5' | R6' |

References

- "Flavonoids". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. November 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Flavone". ChemSpider, Royal Society of Chemistry. 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Lotito, S; Frei, B (2006). "Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: Cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon?". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 41 (12): 1727–46. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033. PMID 17157175.

- David Stauth (5 March 2007). "Studies force new view on biology of flavonoids". EurekAlert!; Adapted from a news release issued by Oregon State University.

- Cermak R, Wolffram S., The potential of flavonoids to influence drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics by local gastrointestinal mechanisms,Curr Drug Metab. 2006 Oct;7(7):729-44.

- Si D, Wang Y, Zhou YH, et al. (March 2009). "Mechanism of CYP2C9 inhibition by flavones and flavonols". Drug Metab. Dispos. 37 (3): 629–34. doi:10.1124/dmd.108.023416. PMID 19074529.

- Sarda SR, Pathan MY, Paike VV, Pachmase PR, Jadhav WN, Pawar RP (2006). "A facile synthesis of flavones using recyclable ionic liquid under microwave irradiation" (PDF). Arkivoc. xvi (16): 43–8. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0007.g05.

- Wessely F, Moser GH (December 1930). "Synthese und Konstitution des Skutellareins". Monatshefte für Chemie. 56 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1007/BF02716040.

- Larget R, Lockhart B, Renard P, Largeron M (April 2000). "A convenient extension of the Wessely-Moser rearrangement for the synthesis of substituted alkylaminoflavones as neuroprotective agents in vitro". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 10 (8): 835–8. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00110-4. PMID 10782697.

- Harborne, Jeffrey B.; Marby, Helga; Marby, T. J. (1975). The Flavonoids - Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2909-9. ISBN 978-0-12-324602-8.

External links

- Flavones at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)