Demographics of South Sudan

South Sudan is home to around 60 indigenous ethnic groups and 80 linguistic partitions among a 2018 population of around 11 million[1][2]. Historically, most ethnic groups were lacking in formal Western political institutions, with land held by the community and elders acting as problem solvers and adjudicators. Today, most ethnic groups still embrace a cattle culture in which livestock is the main measure of wealth and used for bride wealth.

| |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| English and Regional languages | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity |

The majority of the ethnic groups in South Sudan are of African heritage who practice either Christianity or syncretisms of Christian and Traditional African religion. There is a significant minority of people, primarily tribes of Arab heritage, who practice Islam. Most tribes of African heritage have at least one clan that has embraced Islam, and some clans of tribes of Arab heritage have embraced Christianity.

Linguistic diversity is much greater in the southern half of the country, a significant majority of the people belong to either the Dinka people (63.8%) of the South Sudan population, and primary residents of the historic Upper Nile Region and Bahr el Ghazal Region or the Nuer people (10.6%) of the South Sudan population living primarily in the historic Greater Upper Nile region along with a significant number of Dinka. Both peoples speak one of the Nilo-Saharan languages and are closely related linguistically. Dinka is a standard language in South Sudan; however, its dialects are not all mutually intelligible.

Historically, neither the Dinka nor the Nuer have a tradition of centralized political authority and embrace a cattle culture where land is held by the community and livestock is the main measure of wealth. It is common to conduct cattle raids against neighbors. The tribes are fragmented into clans of politically separate communities with customs against intermarriage among clans. Processes of urbanization are a source of significant cultural change and societal conflict.

Population size

It was estimated that the 2018 population of South Sudan was 10,975,927[1][2] with the following age structure:

| Age | Percent | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 years | 46.2% | 2,613,696 | 2,505,794 |

| 15–24 years | 19.7% | 1,148,967 | 1,030,596 |

| 25–54 years | 29% | 1,547,552 | 1,666,242 |

| 55–64 years | 3.1% | 186,460 | 154,924 |

| 65 plus years | 2.1% | 133,300 | 102,600 |

2008 census

The "Fifth Population and Housing Census of Sudan", of Sudan as a whole, was conducted in April 2008. However the census results of Southern Sudan were rejected by Southern Sudanese officials as reportedly "the central bureau of statistics in Khartoum refused to share the national Sudan census raw data with southern Sudan centre for census, statistic and evaluation."[3] The census showed the Southern Sudan population to be 8.26 million,[4] however President Kiir had "suspected figures were being deflated in some regions and inflated in others, and that made the final tally 'unacceptable'."[5] He also claimed the Southern Sudanese population to really be one-third of Sudan, while the census showed it to be only 22%.[4] Many Southern Sudanese were also said to not have been counted "due to bad weather, really poor communication and transport networks, and some areas were unreachable, while many Southern Sudanese remained in exile in neighbouring countries, leading to 'unacceptable results', according [to] southern Sudanese authorities."[5] The chief American technical adviser for the census in the South said the census-takers probably reached 89% of the population.[6] If this estimate is correct, the size of the South Sudanese population is about 9.28 million.

The population count was a determining factor for the share of wealth and power each part of Sudan received. Among the accusations made against the census were that the Sudanese government deliberately manipulated the census in oil-rich regions such as the Abyei district, on the border between northern Sudan and southern Sudan. Another complication is the large population of South Sudanese refugees in the north. The central government inhibited their return.[7]

2009 census

In 2009, Sudan started a new Southern Sudanese census ahead of the 2011 independence referendum, which is said to also include the Southern Sudanese diaspora. However this initiative was criticised as it was to leave out countries with a high share of the Southern Sudanese diaspora, and rather count countries where the diaspora share was low.[8]

Education

In South Sudan, the educational system is modelled after that of the Republic of Sudan. Primary education consists of eight years, followed by three years of secondary education, and then four years of university instruction; the 8 + 3 + 4 system, in place since 1990. The primary language at all levels is English, as compared to the Republic of Sudan, where the language of instruction is Arabic.[9] There is a severe shortage of English teachers and English-speaking teachers in the scientific and technical fields.

Illiteracy rates are high in the country. In 2011, it is estimated that more than 80% of the South Sudanese population cannot read or write. The challenges are particularly severe when it comes to girls; South Sudan has proportionately fewer girls going to school than any other country in the world. According to UNICEF, fewer than one per cent of girls complete primary education. Only one schoolchild in four is a girl and female illiteracy is the highest in the world. Education is a priority for the South Sudanese and they are keen to make efforts to improve the education system.[10]

Demographics statistics

Demographic statistics according to the World Population Review in 2019.[11]

- One birth every 1 minute

- One death every 4 minutes

- One net migrant every 20 minutes

- Net gain of one person every 2 minutes

The following demographic are from the CIA World Factbook[12] unless otherwise indicated.

Population

- 10,204,581 (July 2018 est.)

Age structure

- 0-14 years: 42.3% (male 2,194,952 /female 2,121,990)

- 15-24 years: 20.94% (male 1,113,008 /female 1,023,954)

- 25-54 years: 30.45% (male 1,579,519 /female 1,528,165)

- 55-64 years: 3.82% (male 215,247 /female 174,078)

- 65 years and over: 2.49% (male 145,812 /female 107,856) (2018 est.)

Median age

- total: 18.1 years. Country comparison to the world: 212nd

- male: 18.4 years

- female: 17.8 years (2018 est.)

Birth rate

- 36.9 births/1,000 population (2018 est.) Country comparison to the world: 15th

Death rate

- 19.4 deaths/1,000 population (2018 est.)

Total fertility rate

- 5.34 children born/woman (2018 est.) Country comparison to the world: 10th

Population growth rate

- 1.16% (2018 est.)

Contraceptive prevalence rate

- 4% (2010)

Net migration rate

- -29.2 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2018 est.) Country comparison to the world: 226

Dependency ratios

- total dependency ratio: 83.7 (2015 est.)

- youth dependency ratio: 77.3 (2015 est.)

- elderly dependency ratio: 6.4 (2015 est.)

- potential support ratio: 15.7 (2015 est.)

Urbanization

- urban population: 19.6% of total population (2018)

- rate of urbanization: 4.1% annual rate of change (2015-20 est.)

Religions

- Animist, Christian

Education expenditures

- 1% of GDP (2017) Country comparison to the world: 174th

Literacy

definition: age 15 and over can read and write (2009 est.)

- total population: 27%

- male: 40%

- female: 16% (2009 est.)

Unemployment, youth ages 15-24

- total: 18.5%

- male: 20%

- female: 17% (2008 est.)

Ethnic groups

South Sudan is home to around 60 indigenous ethnic groups.[13][14] About 95% of South Sudanese, among them the Dinka, speak one of the Nilo-Saharan languages, an extremely diverse language family. Nilo-Saharan languages spoken in South Sudan include both Nilotic and non-Nilotic. The other 5% speak languages from the Ubangian family; they occupy the southwest of the country. The most widely spoken Ubangian language in South Sudan is Zande.

By other estimates, there are at least 80 ethnic groups in South Sudan differentiated by various languages and dialects. Some tribes, such as the Dinka have at least 6 different groupings speaking different dialects typically based on geography. Some tribes have clans whose chiefs are the custodian of commonly held land, and a few tribes recognize individual ownership of land with complex inheritance rules among male family members. In still other tribes and clans, the elders are more judicial in nature, with chiefs dealing with conflict resolution. Some tribes are local to South Sudan and others are part of groups that spread across several national boundaries.[15]

In order to maintain ethnic harmony in a part of the world in which tribal conflict is relatively commonplace, one group has proposed the creation of a "House of Nationalities" to represent all 62 recognised groups in Juba.[16] President Salva Kiir Mayardit declared at the ceremony marking South Sudanese independence on 9 July 2011 that the country "should have a new beginning of tolerance where cultural and ethnic diversity will be a source of pride".[17]

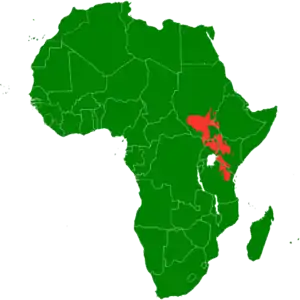

As is true with most of the surrounding countries, the tribe or clan is the primary local social unit, with tribal regions crossing several political boundaries. The Nilotic peoples constitute the bulk of the population of South Sudan, with at least 25 ethnic subdivisions, including Dinka, Nuer, Toposa, and the Shilluk, extending into southwestern Ethiopia, northeastern Uganda, western Kenya, and northern Tanzania. The Nilotic peoples are part of a cattle culture, in which livestock is the main measure of wealth and are used for bride wealth, in which men pay a dowry of several dozen cows to the parents of the woman when they marry, which leads many young men to steal cows from neighboring tribes or clans.

Non-Nilotic people in South Sudan include the Azande, Murle, Didinga, Tennet, Moru, Madi, and Balanda.

Over 5,000 people from Asia and Europe live in South Sudan, representing 0.05% of its total population.[18][19][20]

Dinka People

The Dinka people (part of the Nilotic group) have no centralized political authority, but are instead organized by several independent but interlaced clans. The Dinka people are the largest group in South Sudan, representing 35.8% of the population in 2013[21] (depending on the source, between 1 and 4 million people) and live primarily in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan's historic provence of Bahr el Ghazal. Today, the region consists of the South Sudan states Northern Bahr el Ghazal, Lakes, and Warrap, with significant presence in the historic provence of Greater Upper Nile's states of Jonglei, Upper Nile, and Unity.

Traditionally, the Dinkas believe in one God (Nhialic) who speaks through spirits (jok) that take temporary possession of individuals. British missionaries in the late 19th century introduced Christianity, which now predominates.

The region was one of the scenes of fighting in the First Sudanese Civil War. In 1983 a member of the Dinka group, John Garang de Mabior founded the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, which led to the Second Sudanese Civil War. The SPLA later became the army of South Sudan.

Luo People

The Luo People are primarily found in Kenya (where they are the third largest ethnic group with over 2 million), Tanzania (population just under 2 million), and the South Sudan State of Western Bahr el Ghazal (population about 171,000) - by some accounts the Luo are the 8th largest ethnic group in South Sudan.[15] The Luo seem to be one of the few ethnic groups embracing the concept of individual ownership of property, having a very complex system for inheritance based on the seniority of sons.

Nuer People

The Nuer people (part of the Nilotic group) are the second largest group in South Sudan, representing 15.6% of the population in 2013[21] (or about 1.8 million[15]). In the late 19th century, British, Arab and Turkish traders exerted influence in the area. The Nuer tended to resist the Arab and Turkish, which led to conflict with the Dinka, who supported the British.

Members of the Nuer White Army (named from the practice of using Fly ash on their bodies as an Insect repellent), were originally a group of armed youth formed to protect their cattle from other raiding tribes, and often at odds with their elders. However, they refused to lay down their weapons at the time of South Sudan’s independence for their lack of trust in the SPLA's protection of their community and properties, which led the SPLA to confiscate Nuer cattle, destroying their economy but unsuccessful. The same White Army have clashed with the Murle rebellion and later on fought for relatives massacred in Juba over the SPM crisis.

The Nuer people are significant minorities in the Greater Upper Nile region, consisting of the South Sudan states of Upper Nile, Jonglei, and Unity. The region also has a significant presence from Dinka (and other Nilotic people), the Shilluk people, and Murle people, as well as Moslem Arab tribes.

Shilluk People

Historically, the Shilluk people (part of the Nilotic group) created the Shilluk Kingdom which existed in Southern Sudan from 1490 to 1865. Their king was considered divine, and is now a traditional chieftain within the governments of both Sudan and the South Sudan state of Upper Nile. Most Shilluks have converted to Christianity. The Shilluk Kingdom controlled the White Nile. By the mid 1800s, the Ottomans and Arabs raided the Shilluks for cattle and slaves. Later the British colonized the area as a part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

With a population in South Sudan of just over 381,000, the Shilluk represent the country's 5th largest ethnic group.[15]

The city of Kodok (formerly Fashoda) serves as the mediating city for the Shilluk King. It is a place where ceremonies and the coronation of each new Shilluk King takes place. For over 500 years, Fashoda is believed to be a place where the spirit of Juok (God), the spirit of Nyikango (the founder of Shilluk Kingdom and the spiritual leader of Shilluk religion), the spirit of the deceased Shilluk kings and the spirit of the living Shilluk King come to mediate for the Kingdom of Shilluk's spiritual healing.

Toposa People

Historically, the Toposa people (part of the Nilotic group) were part of the "Karamojong cluster" of present-day Uganda, leaving the area in the late 16th century, eventually settling in eastern part of the State of Eastern Equatoria (part of the historic Equatoria region). Traditionally they lived by herding cattle, sheep and goats, low-level warfare (usually cattle raids, against their neighbors), and in the past were involved in the ivory trade. The Toposa have always competed for water and pasturage with their neighbors, and have always engaged in cattle rustling.

The Toposa have a population of about 207,000 in South Sudan, representing its 6th or 7th largest ethnic group.[15] There is no clear political organization among the Toposa, although respect is paid to elders, chiefs and wise men. Most decisions about the clan or community are made in meetings attended only by the men, traditionally held in the dark hours before the dawn. The Toposa believe in a supreme being and in ancestral spirits.

During the civil wars, they at times supported the SPLA, and at other times supported the army of Sudan.

Otuho People

The Lotuho people (part of the (para) Nilotic group), are primarily a pastoral people numbering over 207,000 (representing its 6th or 7th largest ethnic group[15]) located in Eastern Equatoria. They seem to have migrated to the area in the 1700s and speak Otuho language. Their religion is based on nature and ancestor worship.

Land is held in trust by the community; with no single person in authority. A group of people decide they will make gardens in a certain place, and the group decide the boundaries of each person's garden. Certain areas are fallow (for up to 10 years in the mountains) and other areas open to cultivation (for up to 4 years in the plains), with fallow areas being used for grazing livestock.

In recent times, the Lotuho and their neighbors the Lopit have been in conflict with the Murle people, who have traditionally raided their cattle and abducted their children.

Didinga People

The Didinga (diDinga) occupy the Didinga Hills region in the central part of Eastern Equatoria. They speak the Didinga language (part of the Surmic language family) also spoken by a groups living in southwest Ethiopia from whence they migrated from in the 1700s. Originally embracing the cattle culture, during the civil wars of the 1960s many migrated to Uganda where they were exposed to farming and their children exposed to education. Most returned to the area in the 1970s.

The Didinga practice traditional beliefs and religious practices, including having a tribal Rainmaker who is entrusted with performing certain rituals to bring rain. Didinga also worship and sacrifice to spirits and gods and place great importance upon the worship of dead ancestors.

Tennet People

The Tennet people occupy a region in the western part of Eastern Equatoria and speak the Tennet language. The Tennet have an account of how they were once part of a larger group, which also included what are now Murle, Didinga, and Boya, the other members of the Surmic language family. Tennet people practice Swidden agriculture and are part of the cow culture, which are the main measure of wealth and are used for Bride wealth, and they also hunt, fish, and raise goats and sheep. However, they are primarily dependent on sorghum, and drought can cause severe food shortages.

Tennet communities are governed by the ruling age set, called the Machigi lo̱o̱c. Members of the Machigi Lo̱o̱c are young men who are old enough to participate in warfare (cattle raiding and defense of the village). The Tennet practice traditional beliefs and religious practices, including having a tribal Rainmaker who is entrusted with performing certain rituals to bring rain. Tennet also worships and sacrifice to spirits and gods and place great importance upon the worship of dead ancestors.

Acholi People

The Acholi people (part of the Nilotic group) occupy a region in the western part of Eastern Equatoria and speak the Acholi language. It is estimated that in 2013 there are under 60,000 Acholi in South Sudan, and 1.6 million in Uganda.[15]

The Acholi developed a different sociopolitical order characterized by the formation of Chiefdoms headed by Rwodi who traditionally came from one clan, with each chiefdom containing several villages made up of different patrilineal clans. The Rwodi were traditionally believed to have supernatural powers, but ruled through a Council of Clan Elders; the Council's representatives could mediate issues between clans. This structure has resulted in a society of aristocrats and commoners and has also resulted in the unequal distribution of wealth.

Marriage traditionally requires courting until the young man wins the girl’s consent, then he goes to her father and pays a small betrothal dowry. The betrothal period continues until full payment is made, typically settled in sheep, goats, spears, or hoes.[22]

The Acholi believed in a superior being, Nyarubanga, and the killing of a person was prohibited. If a killing took place, negotiations for blood money were led by the victim's family, followed by rituals of reconciliation to restore the killer to the community and bring peace between the clans. Today most Acholi are Christian.

The land of the Acholi, known as ngom kwaro, is communally owned with access based on the membership to a community, clan, or family. Traditionally this commonly held land in Acholi is used for the purpose of hunting, grazing, cultivation, and settlement, and the Rwodi handle land disputed between the clans.[23]

The Acholi were originally from the Bahr el Ghazal region, but migrated south, to the area of Uganda during the late 17th century, creating Acholiland, and are one of Uganda's major ethnic groups. The Acholi of South Sudan are traditionally not considered part of Acholiland. Acholiland in Uganda is the home of Joseph Kony, who proclaims himself the spokesman of God and a spirit medium and promotes a mixture of Traditional African religion and Christianity, and who leads the Lord’s Resistance Army. Having been forced out of Uganda, it is thought that Kony has moved his movement’s base to South Sudan. Kony's movement has not maintained the traditions of the Acholi people.[24]

dinka/murle People

The Murle live primarily in the State of Jonglei, South Sudan, and practice a blend of African Traditional Religion and Christianity. With a population of about 130,000, the Murle are the 11th largest ethnic group in South Sudan.[15] Elders and witches often act as trouble fixers. The language of the Murle is part of the Surmic language cluster.

The Murle (like the Dinka and Nuer) have a tradition in which men can only marry when they pay a dowry of several dozens of cows. Because of the poverty in the area, the easiest way to secure a bride is to steal cows from other tribes. Historically the youth of the Murle, Dinka and Nuer seem to have equally raided each other for cattle dowries. However, with the civil wars in both Sudan and Ethiopia, they felt unprotected and the Murle formed their own militia.

Azande People

The Azande live primarily in the Congo, South Sudan and the Central African Republic, and speak the Zande language, a language of the Ubangian language family. Most of the 713,000 Azandes in South Sudan live in Western Equatoria, and they are the country's third largest ethnic group.[15] Traditionally, the Azande were conquering warriors who practiced African Traditional Religion which included witchcraft. While most Azande are now Christian, there is a sub-culture that views witchcraft as an inherited substance in the belly which lives relatively independent of the host.

The Azande are sometimes pejoratively known as Niam-Niam (or Nyam-Nyam), which appears to be of Dinka origin, and means great eaters in the Dinka language, supposedly referring to cannibalistic propensities. The Azande are primarily small-scale farmers, historically supplying much of the grain for South Sudan.[25] The Azande also appear to be one of a few groups of people in South Sudan that do not embrace the cow culture, requiring dowries of cows for marriage.

There has historically been conflict with the Dinka and Azande.

Moru People

The Moru are found primarily in Western Equatoria (numbering over 152,000, the country's 10 largest ethnic group[15]) with smaller numbers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. The Moru are highly educated, partly because of the work of the Church Missionary Society, with a large number becoming medical professionals.

Traditionally, there are no formal political institutions. Land is held by the community with the Moru economy agriculturally based, but they have of recent started to acquire livestock. The administrative authority lies with the Paramount chiefs, chiefs, sub-chiefs, head men who adjudicate minor cases of elopement and adultery. Their main role in society is conflict resolution, peace and reconciliation between families and clans.

Historically there have been attacks by the Azande and the raids by slavers from Congo.

Bari People

The Bari people (part of the (para) Nilotic group) occupy the savanna lands of the White Nile Valley and speak the Bari language. Many of the Bari were forced into slavery by Belgians, and used as porters to carry ivory tusks to the Atlantic Coast. Traditionally, the Bari believed in one god along with good and evil spirits. Today most Bari are Christian. Historically, the Bari have defended their land from the Dinka, Azande, as well as Ottoman slave traders.

The Bari number about 475,000 and are the country's 4th largest ethnic group.[15]

The Bari tend to have two weddings, a traditional Bari wedding, typically an arrangement between families, that are sometimes made when the children are as young as 10, includes betrothal and dowry negotiations. Dowry is handed over when betrothed are of marrying age, followed by a Christian wedding. As with most other surrounding tribes, the Bari embrace a cattle culture, the components of a typical traditional Bari dowry are made up of live animals, averaging 23 heads of cattle (cows, calves and bulls), 40 goats and sheep.

Baggara Arabs

The Baggara are Arab tribes, numbering over 1 million, living primarily in Chad and the Sudan's Darfur region (mainly Fur, Nuba and Fallata), but also extend (migrate) to South Sudan and surrounding areas. The northern part of the State of Western Bahr el Ghazal (specifically Raga County) is traditionally part of the Baggara belt. The translation of their Arabic name is "Cowman." The common language of these groups is Chadian Arabic.

The Baggara of Darfur and Kordofan were the backbone of the Mahdist revolt against Turko-Egyptian rule in Sudan in the 1880s. Starting in 1985, the Government of Sudan armed many of the local tribes as militia to fight a proxy war against the Dinka dominated Sudan People's Liberation Army in their areas. During the Second Sudanese Civil War thousands of Dinka women and children were abducted and subsequently enslaved by members of the Missiriya and Rezeigat tribes. An unknown number of children from the Nuba tribe were similarly abducted and enslaved.

Languages

English is the official language.[21] There are over 60 indigenous languages in South Sudan. The indigenous languages with the most speakers are Dinka, Shilluk, Nuer, Bari, and Zande. In the capital city, an Arabic pidgin known as Juba Arabic is used by several thousand people.

Religion

Religion in South Sudan by the 2010 Pew Research on Religion.[26] Note that other sources give differing figures.

Religions followed by the South Sudanese include African Traditional Religion, Christianity and Islam - sources differ regarding proportions. Some scholarly[27][28][29] and U.S. Department of State sources state that a majority of southern Sudanese maintain African Traditional Religion beliefs with those following Christianity in a minority (albeit an influential one). Likewise, according to the Federal Research Division of the US Library of Congress: "in the early 1990s possibly no more than 10% of southern Sudan's population was Christian".[30] In the early 1990s, official records of Sudan claimed that from population of what then included South Sudan, 17% of people followed African Traditional Religion and 8% were Christians. However, some news reports claim a Christian majority,[31][32] and the US Episcopal Church claims the existence of large numbers of Anglican adherents from the Episcopal Church of the Sudan: 2 million members in 2005.[33] Likewise, according to the World Christian Encyclopedia, the Catholic Church is the largest single Christian body in Sudan since 1995, with 2.7 million Catholics mainly concentrated in South Sudan.[34] The Pew Research Center likewise suggests that around 60% of the South Sudanese population are Christian, with around 33% following 'folk religions'.[35] These figures are also disputed as the Pew Research Center on Religion and Public Life report cites 'The United Nations provided the Pew Forum with special estimates for Sudan and the new nation of South Sudan'.[36] The UN does not have any official figures on ethnicity and religion outside National Census figures.

Speaking at Saint Theresa Cathedral in Juba, South Sudanese President Kiir, a Roman Catholic who has a Muslim son, stated that South Sudan would be a nation which respects the freedom of religion.[37] Amongst Christians, most are Catholic and Anglican, though other denominations are also active, and African Traditional Religion beliefs are often blended with Christian beliefs.[38]

Property rights and tribal relations

Historically, the people of the Southern regions of the Sudan were nomadic and land was held by the tribe as communal land. Although land could not be bought, it could be borrowed. Large tracts of land (a “dar”) belonged to the tribe and the custodian was the tribe’s chief. Under this system herders had fairly open access to grazing land for short periods of time, providing farmers with manure and milk, while the farmers provided fodder for the animals, providing a mutually beneficial arrangement.[39]

During the early part of the 19th century the Ottoman Empire invaded the Sudan, searching for slaves, ivory and gold. The Ottomans imposed a legal system that sought to maintain nomadic legal rights by transferring title of commonly held community tribal land to the government, and establishing Usufruct rights of nomadic herders and farmers. However, during the Madhist revolt between 1885 and 1898, large tracts of land were transferred to supporters of the Mahdi; at the end of the revolt, land reverted to previous owners.[39]

In 1899 the British established a Condominium of Egypt and the United Kingdom to control of the area, called Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. A new legal system was established that replaced the tribal system with an ethnic or religious one. In the case of Southern Sudan this meant that land for herding was separated from land for farming, and the government's representative often was a local tribal chief. In 1920 the Sudan applied a Closed District Ordinance whose purpose was to limit the Arab—Islamic influences and preserve the African identity of the South Sudan, which also restricted the movement of nomadic pastoral tribes. Laws were passed 1944, that gave farmers superior rights over herders in land disputes.[40]

At the time of Sudan’s independence in 1956, Northern Moslems were appointed to senior positions in the south. During the 1970, the Unregistered Land Act ended the last remnants of colonial administrative systems, which were replaced by central-state system of leasing land for large farming operations. “These land grabs by the government were also the reasons why so many farmers and pastoralists [herders] that saw their land assimilated into mechanized farming schemes, or simply registered in someone else’s name, joined the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in the late 1980s”[41]

It is arguable that in any culture of tribes and clans that are pastoral, nomadic herders, especially those following the cow culture (where marriage dowries of live cattle and sheep are required), the change from pastoral/nomadic to urban cultures is problematic. Since the tradition of land ownership in these pastoral cultures is of large tracts of land (a "dar") held in common by the tribe (or clan), the imposition of new property laws designed for individual ownership of land for either urban uses or farming is challenging to the existing society. This problem is exacerbated in South Sudan because of its many wars of revolution and civil wars that, over time, established multiple legal owners to the same plots of land, and the displaced people from different tribes may not have the same traditional rights as they did in their communities of origin, which may no longer exist.[42]

References

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "South Sudan parliament throw outs census results". SudanTribune. 8 July 2009.

- Fick, Maggie (8 June 2009). "S. Sudan Census Bureau Releases Official Results Amidst Ongoing Census Controversy". !enough The project to end genocide and crimes against humanity.

- Birungi, Marvis (10 May 2009). "South Sudanese officials decry 'unfortunate' announcement of census results". The New Sudan Vision. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Thompkins, Gwen (15 April 2009). "Ethnic Divisions Complicate Sudan's Census". NPR.

- Broere, Kees. "Uitstel voor census Soedan". de Volkskrant, 15 April 2008, p. 5.

- "South Sudan says Northern Sudan's census dishonest". Radio Nederland Wereldomroep. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- Davidson, Martin (11 January 2011). "Sudan needs English to build bridges between North and South". the Guardian.

- "Severe Challenges Facing Female Education In South Sudan" (PDF). fmreview.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- "South Sudan Population 2019", World Population Review

- "The World FactBook - Sao Tome and Principe", The World Factbook, July 12, 2018

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), 24 December 2009.

- "Distribution of Ethnic Groups in Southern Sudan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- "South Sudan". Joshua Project, a ministry of the US Center for World Mission U.S. Center for World Mission. Retrieved 9 Jan 2014.

- "The House of Nationalities Leaflet". Sudan House of Nationalities Concept. 2010.

- Carlstrom, Gregg (9 July 2011). "South Sudan celebrates 'new beginning'". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- https://www.devex.com/news/aid-workers-explain-what-is-it-like-to-live-and-work-in-remote-south-sudan-95553

- https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/South_Sudan_Jan_2016_english.pdf

- https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/foreign-military-activity-increasing-in-the-horn-of-africa/

- South Sudan. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- "Acholi". Gurtong. p. 1. Retrieved 3 Feb 2014.

- Mrs. Despina Namwembe, ed. (2012). "Mitigating Land Conflicts in Northern Uganda" (PDF). URI & ARLPI, Supported by IFA/ZIVIK. pp. 9, Volume IV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 3 Feb 2014.

- Reggie Whitten and Nancy Henderson (2013). Sewing Hope. Dust Jacket Press. ISBN 978-1-937602-94-9.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Religions in South Sudan - PEW-GRF". Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- Kaufmann, E.P. Rethinking ethnicity: majority groups and dominant minorities. Routledge, 2004, p. 45.

- Minahan, J. Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Press, 2002, p. 1786.

- Arnold, G. Book Review: Douglas H. Johnson, The Root Causes of Sudan's Civil Wars. African Journal of Political Science Vol.8 No. 1, 2003, p. 147.

- Sudan: A Country Study Federal Research Division, Library of Congress – Chapter 2, Ethnicity, Regionalism and Ethnicity

- "More than 100 dead in south Sudan attack-officials" Archived 2011-06-28 at the Wayback Machine SABC News 21 September 2009 Retrieved 5 April 2011

- Hurd, Emma "Southern Sudan Votes To Split From North" Sky News 8 February 2011 Retrieved 5 April 2011

- "How many Anglicans are there in the Anglican Church in North America?" (PDF). fwepiscopal.org.

- World Christian Encyclopedia, eds. David Barrett, Geo. Kurian, Todd Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp 699, 700

- "Global Religious Landscape Table - Percent of Population - Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life". 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013.

- Global Religious Landscape

- "South Sudan To Respect Freedom Of Religion Says GOSS President | Sudan Radio Service". Sudanradio.org. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Christianity, in A Country Study: Sudan, U.S. Library of Congress.

- Thingholm, Charlotte Bruun; Habimana, Denise Maxine (2012). "Formalizing Property Rights in South Sudan: Thesis of the Master Program on Development, International Relations, Global Refugees Studies". Aalborg University Copenhagen. pp. 41–46. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- Thingholm & Habimana 2012, p. 42

- Thingholm & Habimana 2012, p. 45

- Thingholm & Habimana 2012, pp. 42–56