Luo people

The Luo of Kenya and Tanzania are a Nilotic ethnic group native to western Kenya and the Mara Region of northern Tanzania in East Africa. The Luo are the fourth largest ethnic group (10.65%) in Kenya, after the Kikuyu (17.13%), the Luhya (14.35%) and the Kalenjin (13.37%).[1] The Tanzanian Luo population was estimated at 1.1 million in 2001 and 1.9 million in 2010.[2] They are part of a larger group of related Luo peoples who inhabit an area ranging from South Sudan, South-Western Ethiopia, Northern and Eastern Uganda, Northeastern DRC, South-Western Kenya and Northern Tanzania.[3]

A traditional Luo village at the Bomas of Kenya museum. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 7,046,966 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Western Kenya and northern Tanzania | |

| 5,066,966 (2019)[1] | |

| 1,980,000 (2010) | |

| Languages | |

| Dholuo, Swahili, and English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, African Traditional Religion, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Luo peoples | |

| Luo | |

|---|---|

| Person | Jaluo (m)/Nyaluo (f) |

| People | Joluo |

| Language | Dholuo |

| Country | Pinj Luo/Lolwe |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Kenya |

|---|

|

| Cuisine |

|

They speak the Luo language, also known as Dholuo, which belongs to the Western Nilotic branch of the Nilotic language family. Dholuo shares considerable lexical similarity with languages spoken by other Luo peoples.[4]

The Luo descend from migrants who moved into western Kenya from Uganda between the 15th and 20th centuries in four waves. These migrants were closely related to Luo peoples found in Uganda, especially the Acholi and Padhola people. As they moved into Kenya and Tanzania, they underwent significant genetic and cultural admixture as they encountered other communities that were long established in the region.[5][6]

Traditionally, Luo people practised a mixed economy of cattle pastoralism, seed farming and fishing supplemented by hunting.[7] Today, the Luo comprise a significant fraction of East Africa's intellectual and skilled labour force in various professions. They also engage in various trades such as tenant fishing, small-scale farming, and urban work.[8]

Luo people and people of Luo descent have made significant contributions to modern culture and civilisation. Tom Mboya and Oginga Odinga were key figures in the African Nationalist struggle.[9][10] Luo scientists such as Thomas R. Odhiambo (founder of the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) and winner of UNESCO's Albert Einstein Gold Medal in 1991) and Washington Yotto Ochieng (winner of the Harold Spencer-Jones Gold Medal in 2019 from The Royal Institute of Navigation (RIN)) have achieved international acclaim for their contributions.[11][12] Also, Prof. Richard S. Odingo was the Vice chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change when it awarded the Nobel Peace prize in 2007 with Al Gore.[13] Barack Obama, the first black President of the United States of America and Nobel Peace Prize winner was born to a Kenyan Luo father, Barack Obama Sr.[14] The Luo are the originators of a number of popular music genres including Benga and Ohangla. Benga is one of Africa's most popular genres.[15] Lupita Nyong'o, was the first black African to be win an Academy Award in 2014. [16]

Location

The present day homeland of Kenyan and Tanzanian Luo lies in the eastern Lake Victoria basin in the former Nyanza province in Western Kenya and the Mara region in North western Tanzania. This area falls within tropical latitudes and straddles the equator. This area also receives high rainfall averages. The average altitudes range between 3700 and 6000 feet above sea level.[17]

History

Origins

Luo people of Kenya and Tanzania form the majority of Nilotic peoples.[18] During the British colonial period, they were known as Nilotic Kavirondo.[19] The exact location of origin of the Nilotic peoples is controversial but most ethnolinguists and historians place their origins between Bahr-el-Ghazal and Eastern Equatoria in South Sudan. They practised a mixed economy of cattle pastoralism, fishing and seed cultivation.[7] Some of the earliest archaeological findings on record, that describe a similar culture to this from the same region, are found at Kadero, 48 kilometres north of Khartoum in Sudan, and date to 3000 BC. Kadero contains the remains of a cattle pastoralist culture as well as a cemetery with skeletal remains featuring Sub-Saharan African phenotypes. It also contains evidence of other animal domestication, artistry, long-distance trade, seed cultivation and fish consumption.[20][21][22][23] Genetic and linguistic studies have demonstrated that Nubian people in Northern Sudan and Southern Egypt are an admixed group that started off as a population closely related to Nilotic peoples.[24][25] This population later received significant gene flow from Middle Eastern and other East African populations.[24] Nubians are considered to be descendants of the early inhabitants of the Nile valley who later formed the Kingdom of Kush which included Kerma and Meroe and the medieval christian kingdoms of Makuria, Nobatia and Alodia.[26] These studies suggest that populations closely related to Nilotic people long inhabited the Nile valley as far as Southern Egypt in antiquity.

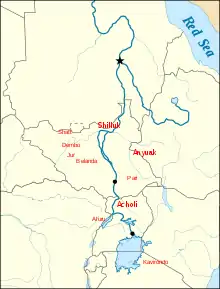

For various reasons, slow and multi-generational migrations of Nilotic Luo Peoples occurred from South Sudan into Uganda and western Kenya from at least 1000 AD continuing up until the early 20th century.[27] Some authors note that the early phases of this expansion coincide with the collapse of the Christian Nubian kingdoms of Makuria and Alodia, the penetration of Arabs into central Sudan as well as Nilotic adoption of Iron Age technology.[28][29] The northern most group of Luo peoples - The Shilluk - advanced north along the White Nile in the 16th century, conquering territory as far as modern day Khartoum.[30] They established the Shilluk Kingdom.[31][32] In the 15th century, Luo peoples moved into the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom and established the Babiito dynasty in Uganda. This group assimilated into Bantu culture. [31]

The Luo of Kenya and Tanzania are classified as Southern Luo.[33]and are the only 'river lake Nilotes' having migrated and lived along the Nile river. They entered Kenya and Tanzania via Uganda from the Bahr el-Ghazal region in South Sudan. The Luo speakers who migrated into Kenya were chiefly from four Luo-speaking groups: the Lango, Acholi, Adhola and Alur people (From Uganda and parts of South Sudan and Eastern Congo), especially Acholi and Padhola.[4][5] It is estimated that Dholuo has 90% lexical similarity with Lep Alur (Alur language); 83% with Lep Achol (Acholi language); 81% with Lango language, 93% with Dhopadhola (Padhola language), 74% with Anuak, and 69% with Jurchol (Luwo) and Dhi-Pari (Pari).[4]

Luo of Kenya and Tanzania are also called Joluo or Jonagi/Onagi, singular Jaluo, Jaonagi or Joramogi/Nyikwaramogi, meaning "Ramogi's heirs." The Luo clans of Kenya and Tanzania were called Ororo, while among the Nuer they were called Liel. In the Dinka tribe the Luo are called the Jur-Chol.[34]The present-day Kenya Luo traditionally consist of 27 tribes, each in turn composed of various clans and sub-clans[35] ("Jo-" indicates "people of").

Migration into Kenya

Oral history and genealogical evidence have been used to estimate timelines of Luo expansion into and within Kenya and Tanzania. Four major waves of migrations into the former Nyanza province in Kenya are discernible starting with the People of Jok (Joka Jok) which is estimated to have began around 1490-1517.[36] Joka Jok were the first and largest wave of migrants into northern Nyanza. These migrants settled at a place called Ramogi Hill then expanded around Northern Nyanza. The People of Owiny' (Jok’Owiny) and the People of Omolo (Jok’Omolo) followed soon after (1598-1625).[5] A miscellaneous group composed of the Suba, Sakwa, Asembo, Uyoma and Kano then followed. The Suba originally were Bantu speaking people who assimilated into Luo culture. They fled from the Buganda Kingdom in Uganda after the civil strife that followed the murder of the 24th Kabaka of Buganda in the mid 18th century and settled in South Nyanza, especially at Rusinga and Mfangano islands.[37] Luo speakers crossed Winam Gulf of Lake Victoria from Northern Nyanza into South Nyanza starting in the early 17th century.[5]

As Luo speakers migrated deeper into western Kenya, they encountered the descendants of various people who had long occupied the region. The great lakes region has been inhabited since the early stone age.[38] The Kanysore culture, located at Gogo falls in Migori county, are thought to be the first hunter gatherers in East Africa to produce ceramics.[39] Twa people are thought to have created the rock art present on Mfangano Island.[40] Bantu speakers, early migrants from West Africa, are thought to have reached western Kenya by 1000BC. They brought with them Iron forging technology and novel farming techniques, turning the great lakes region into one of Africa’s main population centres and earliest Iron smelting regions.[41] The Urewe culture was dominant from 650BC to 550BC. This culture was found in northern Nyanza.[42] Bantu speaking groups found in the Lake Victoria basin today include the Luhya, Suba, Kunta, Kuria and Kisii. Southern Nilotic speakers, the Nandi, Kipsigis and Maasai were also found in this area.[5]

Luo expansion into these already inhabited areas led to trade, conflict, conquest, intermarriage and cultural assimilation. The previous inhabitants were pushed by Luo speakers to their present day boundaries.[43] Luo customs and habits also changed as they adopted the culture of the communities they interacted with.[43] Conflict and raids in this diverse area led to development of defensive savanna architecture typified by the stone walled ruins, Thimlich Ohinga in South Nyanza.[44] Neville Chittick, the director of the British Institute of History and Archaeology in East Africa was the first to assert that the site was likely to have been constructed before the arrival of Luo speakers.[44] This assertion is poorly supported archaeologically however because most of the stone walled structures are dated to within the period of Luo expansion.[45][46] Nevertheless, Luo speakers maintained Thimlich Ohinga and continued the tradition of building stone walled fortresses (Ohingni) as well as defensive earthworks (Gunda Bur) in both Northern and Southern Nyanza. These defensive earth works would curve around living areas surrounding them. Some of these defensive structures enclosed several hundred houses. [47] Archaeological and ethnographic analyses of the sites have shown that the spatial organisation of these structures most closely resembles the layout of traditional Luo homesteads. Ceramic analysis also confirms continuity between the earliest inhabitants of these sites and Luo speakers. [45] With the arrival of the Europeans, these sites were slowly vacated as the colonial administration established peace in the region. The families living in the enclosures moved out into individual homesteads using euphorbia instead of stone as fencing material. By the mid 20th century, they were all abandoned.[45][47]

Colonial times

Early British contact with the Luo was indirect and sporadic. Relations intensified only when the completion of the Uganda Railway had confirmed British intentions and largely removed the need for local alliances. In 1896 a punitive expedition was mounted in support of the Wanga ruler Mumia in Ugenya against the Kager clan led by Ochieng Ger III Otherwise known as Gero. Over 200 were quickly killed by a Maxim gun. 300 people in Uyoma resistance were killed by an expedition led by Sir Charles Horbley (Bwana Obila Muruayi) when they were confiscating Luo cattle to help feed the Indian workers who were building the Uganda railway. Following these clashes, Luo spiritual leaders advised the people to actively cooperate with the British. By 1900, the Luo chief Odera was providing 1,500 porters for a British expedition against the Nandi.[48] The British set up regional headquarters first at Mumias then at Kisumu.They worked to submit the Luo to colonial control and administration. Within a few decades, the traditional leaders and political structures were replaced by colonial chiefs. [49]

The Seventh Day Adventist Church missionaries were amongst the earliest Christian missionaries to proselytise to Luo people. Arthur Carscallen, a Canadian Seventh day Adventist(SDA) was the first SDA Adventist to work in Kenya with Peter Nyambo, from Nyasaland (Present day Malawi). The first mission was opened with the assistance of German missionary Abraham C. Enns, in November 1906 at Gendia Hill, Kendu Bay. These missionaries established stations at Wire Hill, Rusinga Island, Kanyadoto, Karung, Kisii and Kamagambo. These were all in South Nyanza. The first Luo SDA converts were baptised on the 21st of May 1911. Carscallen was the first to reduce Dholuo to writing. He produced a textbook of grammar and started translating the bible into Dholuo.[50] Catholic missionaries and Anglican missionaries through the Church Mission Society (CMS) were also active throughout Nyanza, but mainly focused on Northern Nyanza.[51]

It remains unclear whether Luo people westernised due to colonial pressure or they readily accepted aspects of western culture. However, by the 1930's, the Luo way of life had changed significantly and westernised. [51] Some suggest that the efforts of Chiefs (Ruoth) such as Odera Akang'o played a role in this. In 1915, the Colonial Government sent Odera Akang'o, the ruoth of Gem, to Kampala, Uganda. He was impressed by the British settlement there and upon his return home he initiated a forced process of adopting western styles of "schooling, dress and hygiene". This resulted in the rapid education of the Luo in the English language and English ways. [52] European education carried out by the Christian missionaries also played a role in the westernisation of the Luo. [51]

The apparent acquiescence to British colonial rule was shattered by a movement known as Mumboism that took root in South Nyanza. In 1913, Onyango Dunde of central Kavirondo proclaimed to have been sent by the serpent god of Lake Victoria, Mumbo to spread his teachings. The colonial government recognised this movement as a threat to their authority because of the Mumbo creed. Mumbo pledged to drive out the colonialists and their supporters and condemned their religion. Since violent resistance had been proven to be futile as the Africans were outmatched technologically, this movement focused on anticipating the end of colonialism, rather than actively inducing it. This movement was classified as a millenialist cult. Mumboism spread amongst the Luo and the Kisii people. The Colonial authorities suppressed the movement by deporting and imprisoning adherents in the 1920's and 1930's.[53]

The earliest modern African political organisation in Kenya Colony sought to protest pro-settler policies, increased taxes on Africans and the despised Kipande (Identifying metal band worn around the neck). Mass meetings were organised separately by Luo people in Kavirondo and the Kikuyu people in Nairobi. A strike at the CMS mission school in Maseno was organised by Daudi Basudde. He raised concerns about the damaging implications on African land ownership by switching from the East African Protectorate to the Kenya Colony. A series of meetings dubbed Piny Owacho (Voice of the People) culminated in a large mass meeting held in December 1921 advocating for individual title deeds, getting rid of the Kipande system and a fairer tax system. Bound by the same concerns, James Beauttah, one of the founders of the Kikuyu Central Association initiated an alliance between the Kikuyu and Luo communities.[54] Archdeacon W. E. Owen, an Anglican missionary and prominent advocate for African affairs, formalised and canalised the Piny’ Owacho (Voice of the People) movement. Colonial authorities would come to praise him as having re-directed the political movement which was thought of as premature. However, locals perceived him as their advocate. He started the Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association and became its president, offering Africans an avenue through which they could address their grievances. However, he concentrated primarily on welfare issues and avoided politics that would upset colonial authorities.[55]

Oginga Odinga started the Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation (LUTATCO) after noting that Luo business owners, who were the most financially independent Africans, loathed education. He also sought to uplift the economic status of the Luo community whilst proving that education was useful for business. The LUTATCO office was the first African owned building in Kisumu Town. One of the many business ventures it engaged in included the publication of African Nationalist newspapers including Achieng Oneko's vernacular newspaper Ramogi and Paul Ngei's radical newspaper Uhuru Wa Africa. For his efforts he was appointed as ‘Ker’ or Chief of the Luo Union, an organisation that represented the interests of the greater Luo Peoples in East Africa.[56] Oginga Odinga would become a Key political figure in Kenya. He first ventured into politics when he joined the Kenya African Union. Harry Thuku, a pioneering Kikuyu politician, founded the Kenya African Study Union in 1944 which later became the Kenya African Union. This was an African nationalist organisation that demanded amongst other things, access to white owned land. It was multitribal. Jomo Kenyatta became president of KAU in 1947. In an effort to gain nationwide support of KAU, Jomo Kenyatta visited Kisumu in 1952. His effort to build up support for KAU in Nyanza inspired Oginga Odinga, the Ker (chief) of the Luo Union to join KAU and delve into politics. [57]

Mau Mau Uprising

.jpg.webp)

The Luo generally were not dispossessed of their land by the British, avoiding the fate that befell the pastoral ethnic groups inhabiting the Kenyan "White Highlands". Many Luo played significant roles in the struggle for Kenyan independence, but the people were relatively uninvolved in the Mau Mau Uprising (1952–60). Instead, they used their education to advance the cause of independence peacefully. An intense propaganda campaign by the colonial government effectively discouraged other Kenyan communities, settlers and the international community from sympathising with the movement by emphasising on real and perceived acts of barbarism perpetrated by the Mau Mau. Although a much smaller number of Europeans lost their lives compared to Africans during the uprising, each individual European loss of life was publicised in disturbing detail, emphasising elements of betrayal and bestiality.[10] As a result, the protest was mainly supported by the Kikuyu who began the uprising. Luo supporters of Mau Mau and those deemed by the colonial government to support it were imprisoned as well. Most notably, Ramogi Achieng Oneko, a KAU leader and one of the Kapenguria six. Barack Obama's grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama, was involved in the African nationalist movement. He was imprisoned and tortured by the colonial authorities on suspicions that he was involved in the Mau Mau rebellion.[58] Luo lawyer Argwings Kodhek, the first East African to obtain a law degree, became known as the Mau Mau lawyer as he would successfully defend Africans accused of Mau Mau crimes pro bono. [59]

Pre-Independence Politics

.jpg.webp)

Following the suppression of the Mau Mau uprising and containment of Kikuyu politicians, Luo anticolonial activists filled the gap, achieving prominence on the political scene. Tom Mboya, a Suba Luo, stepped into the limelight and became one of the major figures in the struggle for Kenya’s independence. His intelligence, discipline, oratory and organisational skills set him apart. Tom Mboya started the Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL), which quickly became the most active political body in Kenya, representing all the trade unions. Mboya’s successes in trade unionism earned him respect and admiration. Mboya established international connections, particularly with labour leaders in the United States of America through the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU). He used these connections and his international celebrity status to counter moves by the colonial government [60] [61] Tom Mboya started the Nairobi People’s Convention Party (NPCP), inspired by Kwame Nkurumah’s People’s Convention Party. It became the most organised and effective political party in the country.[62] It later merged with the Kenya Independence Movement and KAU to form the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which would go on to rule the country until 2002. Tom Mboya also started the Kennedy Airlift scholarship program in order to address the issue of a lack of African skilled labour. Over 800 Kenyans and East Africans benefited from this program including environmentalist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, former vice president George Saitoti and Barack Obama's father, Barack Obama Sr. [63][64]

The first election for African Members of the Legislative Council (MLCs) was in 1957. Tom Mboya and Oginga Odinga were elected.[65] In June 1958, Oginga Odinga called for the release of Jomo Kenyatta who had been imprisoned following the crackdown on the Mau Mau uprising. He made this call at a Legislative council debate. He endured months of persecution for taking this stand before it became the rallying call for the African nationalist movement.[66] The Lancaster House Conferences were held in London to discuss Kenya's independence and constitutional framework. Tom Mboya and Oginga Odinga enlisted the assistance of Thurgood Marshall, an American Lawyer and civil rights activist to draft the first constitution.[67][64]

Independent Kenya

After Kenya became independent on 12 December 1963, Oginga Odinga declined the presidency of Kenya and agreed to assume the vice presidency with Jomo Kenyatta as the head of government. Their administration represented the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party. The Luo and the Kikuyu inherited the bulk of political power in the first years following Kenya's independence in 1963.[10] However, differences with Kenyatta caused Odinga to defect from the party and abandon the vice presidency in 1966. Cold war political intrigues were at play in local Kenyan politics.[68] The western and eastern blocs actively sought to influence local policy making and win allies resulting in a proxy cold war in Kenya. Local politics became enmeshed with cold war ideological divisions. [69] Odinga and Bildad Kaggia, a Kikuyu politician and Mau Mau leader, criticised the Kenyatta government for adopting a corrupt land redistribution policy that did not benefit the poor and landless. Pio Gama Pinto, a prominent anti-colonial activist, Odinga’s chief tactician and link to the eastern bloc was assassinated on 25th February 1965 in what is recognised as Kenya’s first political assassination. Odinga became increasingly sidelined in government and was eventually compelled to resign and start his own political party – the Kenya People’s Union (KPU). [70] The Kenya People's Union (KPU) had strong support amongst the Luo.[71] The Kenyatta government persecuted this party. A security Act was passed in Parliament in July 1966 that permitted the government to carry out detention without trial ostensibly to maintain law and order in situations where the current order was threatened. This Act was immediately used against KPU members.[72] In August 1966, government police arrested prominent Luo KPU members including Ochola Mak'Anyengo (the secretary general of the Kenya Petroleum Oil Workers Union), Oluande Koduol (Oginga Odinga’s private secretary) and Peter Ooko (the general secretary of the East African Common Services Civil Servants Union) and detained without trial.[73]

The Cold war intrigues reached their peak in 1969. Since Odinga's exit from KANU, the Luo increasingly became politically marginalised. Argwings Kodhek, the pioneering Mau Mau lawyer died in a car crash under mysterious circumstances on January 29th 1969. Tom Mboya, widely touted as the heir apparent to Kenyatta, was assassinated 6 months after on 5th July 1969. The political tension led to the Kisumu massacre when Kenyatta's presidential guard and police forces shot and killed several civilians in Kisumu Town, the capital of Nyanza Province. Following this massacre, KPU was banned, turning Kenya into a de facto one party state. All KPU members were arrested and detained without trial, including Oginga Odinga. The political marginalisation of Nyanza province worsened and continued under the Moi administration.[74][75][76][69]

Oginga Odinga was released from detention in 1971. The government continued to discourage his active participation in politics as he could not run for office in the 1974 general elections. [77] In 1982, Odinga attempted to start a new political party - Kenya African Socialist Alliance.[78] Section 2A of the Kenyan constitution was amended making Kenya a de jure one party state therefore preventing Odinga's efforts. A coup attempt that same year by Kenya Air Force soldiers in August, led by a Luo, Hezekiah Ochuka was foiled. Oginga Odinga and his son Raila Odinga were accused of involvement and detained without trial for several months.[78][79][80] These events led to many years of marginalisation of the Luo community. The perception of marginalisation was further enforced by the murder of Robert Ouko, the Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1990.[81] Economic and political marginalisation of the community and disastrous economic management in Kenya, particularly under the KANU party's administration of the nascent state, had tragic consequences for the people of Kenya. Despite the economic potential of nearby Lake Victoria, Kenya continues to struggle with poverty and HIV/AIDS.[82]

Local and international pressure in the early 1990's resulted in the Moi government repealing the amendment of section 2A of the constitution. Multi-party politics was therefore permitted in Kenya.[83] The Forum for Restoration of Democracy (FORD), a multi-tribal opposition party led by Oginga Odinga, Kenneth Matiba and Martin Shikuku was formed. This party split up due to internal wrangling into ethnic based opposition parties - FORD-Asili (led by Matiba) and FORD-Kenya (led by Oginga Odinga).[84] Oginga Odinga died in 1994.

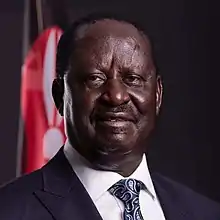

Ford-Kenya later split and Odinga's son, Raila Odinga started the National Development Party of Kenya (NDP) which had considerable Luo support. This party merged with KANU in 2002, just before the general elections. [85] Raila Odinga is widely credited with enabling Mwai Kibaki to win the 2002 presidential election through the support of his Liberal Democratic Party. This relationship turned sour however and Raila Odinga led the vote against Mwai Kibaki in the 2005 Kenyan constitutional referendum which was widely perceived as a referendum against Kibaki. [86] More than 1,000 people were killed and 600,000 displaced in the 2007–2008 Kenyan crisis following the 2007 general elections. The campaign and election period were heavily polarised along ethnic lines. Raila Odinga led the Orange Democratic Movement against Mwai Kibaki's Party of National Unity. [87] A power sharing agreement mediated by Kofi Annan led to a coalition government with Raila Odinga receiving the new position of Prime Minister. [88] The ethnic rivalry between the Kikuyu and the Luo underscores deeply rooted historical issues that involve access to resources and power. This rivalry continues to shape Kenya's political trajectory. [89][90][91]

Despite the polarised politics that has led to economic and political marginalisation, several members of the Luo community continue to achieve prominence in Kenya. These include, James Orengo, Professor Anyang' Nyong'o, Peter Oloo-Aringo, Dalmas Otieno and Peter Ombija. Dr. PLO Lumumba who is the former Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission director is also a Luo. Lupita Nyong'o won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in the film 12 Years a Slave in 2014. Prominent Luo doctors and scientists include the late Prof. David Peter Simon Wasawo, the first science professor in East and Central Africa and first black East African to study and lecture science courses at Makerere university; Thomas R. Odhiambo, prominent entomologist, founder of the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) and the African Academy of Sciences, winner of the Albert Einstein Gold Medal (1991); Washington Yotto Ochieng, winner of the Harold Spencer-Jones Gold Medal 2019 from The Royal Institute of Navigation (RIN) following his outstanding contribution to navigation; Prof. Henry Odera Oruka, philosopher; Professor George Magoha, a consultant urologist and former Vice-Chancellor of University of Nairobi; and Prof Richard Samson Odingo, vice-chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which received the 2007 Nobel peace prize.[13][16][92]

Genetics

Tishkoff et al in 2009 published the largest study done to characterise genetic variation and relationships among populations in Africa. They examined 121 African populations, 4 African American populations and 60 non-African populations. Their results indicated a high degree of mixed ancestry reflecting migration events. In East Africa, all population groups examined had elements of Nilotic, Cushitic and Bantu ancestry amongst others to varying degrees. They also found that by and large, genetic clusters were consistent with linguistic classification with notable exceptions including the Luo of Kenya. Despite being Nilo-Saharan speakers, the Luo cluster with the Niger-Kordofanian speaking populations that surround them. They suggest that this indicates a high degree of admixture occurred during the southward migration of Southern Luo.[6] David Reich’s laboratory also noted similar findings. They found that mutation frequencies in the Luo were much more similar to those of the surrounding Bantu speakers. They suggested that Luo speakers in East Africa may not have always been socially disadvantaged as they migrated into territories already inhabited by Bantu speakers. This is in keeping with oral history which affirms that large groups of Bantu speakers adopted Luo language, culture and customs that were dominant at the time. [93]

Culture and customs

Traditional system of government

Traditionally, the Luo people were a patriarchal society with a decentralized government system.[94] The family was headed by the father or the first wife mikayi or son in the absence of the father. Many families came together through a traced relations by blood to form a clan, anyuola, which mostly brought together the heads of different families together as people of the same descent, jokang'ato. Many clans came together to form a village called gwengwhich was headed by a village elder titled dodo or jaduong' gweng' who ruled with the assistance of elders who were traditionally men of status gained through commerce, wealth, war, or eloquence. Many villages came together to form a sub-tribe which was headed by a hereditary chieftaincy by the eldest son Ruoth. The Luo government structure was stronger at the sub-tribe level under Ruoth who had a council of elders, galamoro mar jodongo or jodong gweng', from all the villages in their territory. The Luos organized their defense and security at the sub-tribe level which was headed by a commander, Osumba Mrwayi, who was part of the council of elders. The council also had a spokesperson who talked on behalf of the council in official matters in village market meetings, religious, and cultural ceremonies that Ruoth presided over.[95][96] Sub-tribe relations with each other was ad-hoc as there was no single ruler of the Luo people. Sub-tribes came together during calamities, war, and natural disasters like drought, famines, and floods to help each other. Sumo, the act of sharing produce with people who were struck by famine was a common tradition with Kisumo being one of the renowned marketplaces where those who were struck by famine never missed the generosity of their Luo counterparts. The concept of a Luo ruler ker was coined by Jaramogi Oginga Odinga during the formation of the Luo Union in 1947 that was aimed at uniting all people of Luo descent in East Africa. Jaramogi Oginga Odinga was the first Luo Ker. As part of distinguishing a tribal leader from a national leader, part of the conditions was that a Luo Ker would not go into national politics and when Jaramogi Oginga Odinga went into national politics in 1957, he had to quit being a Ker.[97]

In recent years, the Luo Ker seat has been claimed by different factions of Luo council of elders that started with the appointment of Willis Opiyo Otondi by Raila Odinga in 2010 to replace Ker Riaga Ogalo. Traditionally, the Ker was elected by a Council of Elders and was not appointed as it happened with Opondo Otondi, and a Luo Ker could only leave office under two conditions, resignation or death. Ker Riaga Ogalo argued that he had not resigned nor died to warrant the appointment of another Ker while Opiyo Otondi argued that he was the duly elected Ker of the Luo people. Ker Riaga Ogalo represented Raila in numerous political forums and helped build Raila Odinga's political career contrary to the requirements of the council during the days they were in good talking terms.[98]

Ker Riaga Ogalo is credited for having progressive ideas of all modern Luo Kers by championing for circumcision of the Luo men to help in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Circumcision was alien to the Luo tradition but his leadership made many hearts to accept the new changes. Ker Riaga Ogalo also served as the Vice-Chairman of the National Council of Elders. During the last years of his reign, he argued that Raila was deterring the Luo People to grow democratically and economically with his style of polictics. Ker Riaga Ogalo died in 2015 after a kidney infection at the Kenyatta National Hospital. The Council's wrangles continued after his demise with today Willis Opiyo Otondi still claiming to be the legitimate ker rivalled by Ker Nyandiko Ong'adi who was elected by the Luo Council of Elders in 2015 to replace ker Riaga Ogalo.[99] The attempt to centralize the Luo people under one authority have not been easy given their history with a decentralized government structure.[100]

Rites of passage

Traditionally, the names given to children often reflected the conditions of the mother's pregnancy or delivery (including, for example, the time or season).[101]

Further, the Luos have traditionally practiced the removal of six lower teeth between the ages of twelve and sixteen.[101] This practice has now fallen largely out of use.

Cuisine

A popular Luo meal includes fish (rech) especially tilapia (ngege) and omena, usually accompanied with ugali (called kuon in Dholuo) and traditional vegetables like osuga and apoth. Many of the vegetables eaten by the Luo were shared after years of association with their Bantu neighbours, the Abaluhya and the Abagusii. Traditional Luo diet consisted of kuon made of sorghum or millet accompanied by fish, meat, or vegetable stews.[102]

Religious customs

Like many ethnic communities in Uganda, including the Langi, Acholi, and Alur, the Luo do not practice the ritual circumcision of males as initiation.

Local churches include Legio Maria, Roho, Nomiya and Fweny among others.[103]

Marriage customs

Historically, couples were introduced to each other by matchmakers, but this is not common now. Like many other communities in Kenya, marriage practices among the Luo have been changing and some people are moving away from the traditional way of doing things.

The Luo successfully expanded their culture through intermarriage with other groups in the region, and many Luo today continue to marry outside the Luo community.[101] The traditional marriage ceremony takes place in two parts, both involving the payment of a bride price by the groom. The first ceremony, the Ayie, involves a payment of money to the mother of the bride; the second stage involves giving cattle to her father. Often these two steps are carried out at the same time, and, as many modern Luos are Christians, a church ceremony often follows.

Music

Traditionally, music was the most widely practiced art in the Luo community. At any time of day or night, music would be made. Music was not played for its own sake. Music was functional, being used for ceremonial, religious, political, or incidental purposes. Music was performed during funerals (Tero buru), to praise the departed, to console the bereaved, to keep people awake at night, and to express pain and agony. It was also used during cleansing and chasing away of spirits. Music was also played during ceremonies like beer parties (Dudu, ohangla dance), welcoming back the warriors from a war, during a wrestling match (Olengo), during courtship, etc. Work songs also existed. These were performed both during communal work like building, weeding, etc. and individual work like pounding of cereals, or winnowing. Music was also used for ritual purposes like chasing away evil spirits (nyawawa), who visit the village at night, in rain making, and during divination and healing.

The Luo music was shaped by the total way of life, lifestyles, and life patterns of individuals of this community. Because of that, the music had characteristics which distinguished it from that of other communities. This can be seen, heard, and felt in their melodies, rhythms, mode of presentation and dancing styles, movements, and formations.

The melodies in Luo music were lyrical, with a lot of vocal ornamentations. These ornaments came out clearly, especially when the music carried an important message. Their rhythms were characterized by a lot of syncopation and acrusic beginning. These songs were usually presented in solo-response style, although some were solo performances. The most common forms of solo performances were chants. These chants were recitatives with irregular rhythms and phrases, which carried serious messages. Most of the Luo dances were introduced by these chants. One example is the dudu dance.[104]

Another unique characteristic in the Luo music is the introduction of yet another chant at the middle of a musical performance. The singing stops, the pitch of the musical instruments go down and the dance becomes less vigorous as an individual takes up the performance is self-praise. This is referred to as Pakruok. There was also a unique kind of ululation, Sigalagala, that marked the climax of the musical performance. Sigalagala was mainly done by women.

The dance styles in the Luo folk music were elegant and graceful. They involved either the movement of one leg in the opposite direction with the waist in step with the syncopated beats of the music or the shaking of the shoulders vigorously, usually to the tune of the nyatiti, an eight-stringed instrument.

Adamson (1967) commented that Luos clad in their traditional costumes and ornaments deserve their reputation as the most picturesque people in Kenya. During most of their performances, the Luo wore costumes and decorated themselves not only to appear beautiful, but also to enhance their movements. These costumes included sisal skirts (owalo), beads (Ombulu / tigo) worn around the neck and waist, and red or white clay worn by the ladies. The men's costumes included kuodi or chieno, a skin worn from the shoulders or from the waist respectively to cover their nakedness, Ligisa, the headgear, shield and spear, reed hats, and clubs, among others. All these costumes and ornaments were made from locally available materials.

The Luo were also rich in musical instruments which ranged from percussion (drums, clappers, metal rings, ongeng'o or gara, shakers), strings (e.g., nyatiti, a type of lyre; orutu, a type of fiddle), wind (tung (instrument)|tung' a horn,Asili, a flute, A bu-!, to a specific type of trumpet).

Currently the Luo are associated with the benga style of music. It is a lively style in which songs in Dholuo, Swahili, or English are sung to a lively guitar riff. It originated in the 1950s with Luo musicians like George Ramogi and Ochieng' Kabaselle trying to adapt their traditional dance rhythms to western instruments. The guitar (acoustic, later electric) replaced the nyatiti as the string instrument. Benga has become so popular that it is played by musicians of all ethnicities like mugithi among the Kikuyu, and it is no longer considered a purely Luo style. It has become Kenya's characteristic pop sound.[105]

Luo singer and nyatiti player Ayub Ogada received widespread exposure in 2005 when two of his songs were featured in Alberto Iglesias' Academy Award-nominated score for Fernando Mereilles' film adaptation of The Constant Gardener.

Other Luo musicians, in various genres, are Akothee, Suzanna Owiyo, Daniel Owino Misiani, Collela Mazee, Achieng' Abura, George Ramogi, Musa Juma, Tony Nyadundo and Onyi Papa Jey.

Kinship, Family, and Inheritance

Ocholla Ayayo writes in "Traditional Ideology and Ethics among the southern Luo":[106]

"When the time of the inheritance comes the ideology of seniority is respected: the elder son receives the largest share, followed in the order of seniority. If it is the land to be divided, for instance, the land of the old grandfather's homestead, the senior son gets the middle piece, the second the land to the right hand side of the homestead, and the third son takes the land on the left hand side. After the father's death the senior son takes over the responsibilities of leadership. These groups when considered in terms of genealogy, are people of the same grandfather, and are known in Dholuo as Jokakwaro. They share sacrifices under the leadership of the senior brother. If the brother is dead the next brother in seniority takes the leadership of senior brother. The responsibility and prestige position of leadership is that it puts one into the primary position in harvesting, cultivation, as well as in eating specified parts of the animal killed, usually the best parts. It is the senior brother, who is leading in the group, who can first own the fishing boat. Since it is he who will be communicating with the ancestors of their father or grandfather, it is he who will conduct or lead the sacrifices of religiousity of the boat, as we have noted earlier. [...] The system of the allocation of land by the father while he is still alive is important since it will coincide with the system of inheritance of land. The principle of the division of the land in monogamous families is rather simple and straightforward. [...] The senior son takes the centre portion of all the land of the homestead up to and beyond the gate or to the buffer zone; the second son then has the remainder of the land to divide with the other brothers. If the land is divided among the elder sons after they are married, and take to live in their lands, it often happens that a youngest son remains in the village of the father to care for him in his old age. His inheritance is the last property, called Mondo and the remaining gardens of his mother. [...] In the case of a polygamous village, the land is divided along the same lines, except that within the village, the sons claim the area contiguous to the houses of their mother. Each wife and her children are regarded as if the group constituted was the son of a single woman.By that I mean the children of the senior wife, Mikayi, are given that portion of the total area which could have been given to the senior son in a monogamous family. The sons of Nyachira, the second wife, and the sons of Reru, the third wife, lay claim to those portions which would have fallen to the second and third sons of Mikayi in a monogamous village".[107]

Paul Hebinck and Nelson Mango explain in detail the family and inheritance system of the Luo in their article "Land and embedded rights: An analysis of land conflicts in Luoland, Western Kenya."[108] Parker MacDonald Shipton also writes extensively about kinship, family and inheritance among the Luo in his book "Mortgaging the Ancestors: Ideologies of Attachment in Africa":

"Outside the homestead enclosure, or (where there is no more enclosure) beyond and before its houses, Luo people have favored a layout of fields that in some ways reflects placements of houses within. The following pattern, as described in Gordon Wilson’s work from the 1950s, is still discernable in our times—not just in informants’ sketches of their ideals, but also in the allocations of real lands where space has allowed following suit. If there is more than one son in a monogamous homestead, the eldest takes land in front of or to the right of the entrance, and the second son takes land on the left. The third receives land to the right and center again, but farther from the father's homestead. The fourth son, if there is one, goes to the left but farther from the paternal homestead than the second. Further sons alternate right and left. While elder sons might thus receive larger shares than the younger ones, the youngest takes over the personal garden (mondo) kept by the father for his own use—as if as a consolation prize".

List of Notable Kenyan and Tanzanian Luo and People of Luo Descent

- Notable people

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Raila Odinga

Raila Odinga

Former Prime Minister of Kenya. African Union High Representative for Infrastructure Development

.jpg.webp)

Academics, Medicine and science

Business and Economics

Politics, activism, trade unionism, diplomacy and law

- Dennis Akumu

- Elijah Omolo Agar

- Wilson Ndolo Ayah

- Evans Odhiambo Kidero

- Patrick Loch Otieno Lumumba

- Ochola Ogaye Mak’Anyengo

- Pamela Odede Mboya

- Tom Mboya

- Miguna Miguna

- Anyang’ Nyong’o

- Auma Obama

- Barack Obama

- Malik Obama

- Sarah Onyango Obama

- Oburu Odinga

- Oginga Odinga

- Raila Odinga

- Joshua Orwa Ojode

- John Henry Okwanyo

- Peter Oloo-Aringo

- Patrick Ayiecho Olweny

- Raychelle Awour Omamo

- William Odongo Omamo

- Ramogi Achieng Oneko

- Dalmas Otieno

- Robert Ouko

- Raphael Tuju

Arts, music and media

- Lydia Achieng Abura

- Dan "chizi" Aceda

- Akothee

- Catherine Susan Anyango

- Esther Arunga

- Gaylyne Ayugi

- Okatch Biggy

- Tedd Josiah

- Princess Jully

- Musa Juma

- Larry Madowo

- Gidi Gidi Maji Maji

- Daniel Owino Misiani

- Mercy Myra

- Tony Nyadundo

- Lupita Nyong’o

- Ayub Ogada

- Joseph Olita

- Sidede Onyulo

- Suzzana Owíyo

- George Ramogi

Writers and playwrights

Sports

- Conjestina Achieng

- Daniel Adongo

- Teddy Akumu

- Andrew Amonde

- Collins Omondi Obuya

- David Oluoch Obuya

- Billy Odhiambo

- Rees Odhiambo

- Thomas Odoyo

- David Johnny Oduya

- Joseph Okumu

- Dennis Oliech

- Michael Olunga

- Johanna Omolo

- Eric Johana Omondi

- Brian Onyango

- Lameck Onyango

- Peter Opiyo

- Arnold Origi

- Divock Origi

- Ian Otieno

- David Otunga

- David Owino

- Eric Ouma

- David Tikolo

- Steve Tikolo

- Tom Tikolo

See also

- Arthur Carscallen, as superintendent of the Seventh Day Adventist Mission in British East Africa from 1906–1921, he compiled and published the first Dholuo grammar and dictionary.

- Kisumu City - The third-largest city in Kenya

- Gor Mahia FC - A Kenyan football club

- Legio Maria, a large religious group originating in Luoland

- Luo peoples - several ethnically and linguistically related Nilotic ethnic groups

- Luo Union (Welfare Organisation) - An defunct East African welfare organisation that united Luo peoples

Sources

- Kyle Keith. "The Politics of The Independence of Kenya." Palgrave MacMillan 1999

- Ogot, Bethwell A., History of the Southern Luo: Volume I, Migration and Settlement, 1500–1900, (Series: Peoples of East Africa), East African Publishing House, Nairobi, 1967

- Reich, David. Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group (27 March 2018). ISBN 110187032X

References

- "2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume IV: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics". Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Gordon, Jr., Raymond G. (editor) (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth Edition. Dallas, Texas, USA: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6. Archived from the original on 2007-11-24.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Ogot 1967, p. 40-47.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Nilotic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Ogot 1967, p. 144-154.

- Tishkoff, S. A.; Reed, F. A.; Friedlaender, F. R.; Ehret, C.; Ranciaro, A.; Froment, A.; Hirbo, J. B.; Awomoyi, A. A.; Bodo, J.-M.; Doumbo, O.; Ibrahim, M.; Juma, A. T.; Kotze, M. J.; Lema, G.; Moore, J. H.; Mortensen, H.; Nyambo, T. B.; Omar, S. A.; Powell, K.; Pretorius, G. S.; Smith, M. W.; Thera, M. A.; Wambebe, C.; Weber, J. L.; Williams, S. M. (22 May 2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–1044. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.

- Ogot 1967, p. 40-42.

- Odede, Fredrick Argwenge; Hayombe, Dr. Patrick O.; G. Agong’, Prof. Stephen (24 July 2017). "Exploration of Food Culture in Kisumu: A Socio-Cultural Perspective". Journal of Arts and Humanities. 6 (7): 74. doi:10.18533/journal.v6i7.1162.

- Kyle 1999, p. 53-89.

- The Politics of The Independence of Kenya by Kyle Keith. Palgrave MacMillan 1999

- Thomas Odhiambo Visionary entomologist harnessing science for Africa's poor. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2003/jun/23/guardianobituaries.highereducation1 Cited 17-12-20

- PROFESSOR WASHINGTON Y. OCHIENG. Imperial College London. Available from: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/people/w.ochieng

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Nobel Lecture. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2007/ipcc/26114-intergovernmental-panel-on-climate-change-nobel-lecture-2007/ Cited 17-12-20

- Obama, Barack (1995). Dreams from My Father. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9781400082773

- Remembering benga: Kenya's infectious musical gift to Africa. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/09/music-benga-kenya-guitar-finger-picking

- "'Pride of Africa: Kenya celebrates Nyong'o's Oscar". Boston Herald. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Ogot, Bethwell A., History of the Southern Luo: Volume I, Migration and Settlement, 1500–1900, (Series: Peoples of East Africa), East African Publishing House, Nairobi, 1967 p31-39

- Ogot 1967, p. 41.

- Joyce, Thomas Athol (1911). "Kavirondo". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 701.

- Krzyzaniak, Lech (December 1976). "The Archaeological Site of Kadero, Sudan". Current Anthropology. 17 (4): 762. doi:10.1086/201823. S2CID 144379335.

- Marshall, Fiona; Hildebrand, Elisabeth (2002). "Cattle Before Crops: The Beginnings of Food Production in Africa". Journal of World Prehistory. 16 (2): 99–143. doi:10.1023/A:1019954903395. S2CID 19466568.

- Achilles Gautier. The faunal remains of the Early Neolithic site Kadero, Central Sudan. Archaeology of Early Northeastern Africa Studies in African Archaeology 9. Available from: https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeum/reader/download/218/218-30-76968-1-10-20170210.pdf

- Krzyzaniak, Lech (April 1978). "New Light on Early Food-Production in the Central Sudan". The Journal of African History. 19 (2): 159–172. doi:10.1017/S0021853700027572.

- Hollfelder, Nina; Schlebusch, Carina M.; Günther, Torsten; Babiker, Hiba; Hassan, Hisham Y.; Jakobsson, Mattias (24 August 2017). "Northeast African genomic variation shaped by the continuity of indigenous groups and Eurasian migrations". PLOS Genetics. 13 (8): e1006976. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006976. PMC 5587336. PMID 28837655.

- Rilly, Claude (2016). "The Wadi Howar Diaspora and its role in the spread of East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millenia BCE". Faits de Langues. 47 (1): 151–163. doi:10.1163/19589514-047-01-900000010.

- Cooper, Julien (2017). "Toponymic Strata in Ancient Nubia until the Common Era". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 4. doi:10.5070/d64110028.

- Ogot 1967, p. 41-43.

- Robertshaw, Peter (July 1987). "Prehistory in the upper Nile Basin". The Journal of African History. 28 (2): 177–189. doi:10.1017/S002185370002973X.

- Oliver, Roland (1982). "The Nilotic Contribution to Bantu Africa". The Journal of African History. 23 (4): 433–442. doi:10.1017/S0021853700021289. JSTOR 182034.

- Martell, Peter (2018). First Raise a Flag. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1849049597.

- Ogot 1967, p. 44-47.

- Mercer, Patricia (1971). "Shilluk Trade and Politics from the Mid-Seventeenth Century to 1861". The Journal of African History. 12 (3): 407–426. doi:10.1017/S0021853700010859. JSTOR 181041.

- Ogot 1967, p. 44-144.

- Odhiambo, Atieno. (1989). Siaya : the Historical Anthropology of an African Landscape. J. Currey. OCLC 1096480559.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1967). History of the Southern Luo: Volume I, Migration and Settlement, (Series: Peoples of East Africa). East African Publishing House, Nairobi. p. assim.

- Ogot 1967, p. 144.

- Ogot 1967, p. 212.

- Ogot 1967, p. 135.

- Dale, Darla; Ashley, Ceri Z. (April 2010). "Holocene hunter-fisher-gatherer communities: new perspectives on Kansyore Using communities of Western Kenya". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 45 (1): 24–48. doi:10.1080/00672700903291716. S2CID 161788802.

- Kenya - Trust for African Rock Art. Available from: https://africanrockart.org/rock-art-gallery/kenya/ Cited 10-11-20

- Ehret, Christopher (2001). "Bantu Expansions: Re-Envisioning a Central Problem of Early African History". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 34 (1): 5–41. doi:10.2307/3097285. JSTOR 3097285.

- Lane, Paul; Ashley, Ceri; Oteyo, Gilbert (January 2006). "New Dates for Kansyore and Urewe Wares from Northern Nyanza, Kenya". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 41 (1): 123–138. doi:10.1080/00672700609480438. S2CID 162233816.

- Ogot 1967, p. 128.

- Ogot 1967, p. 218.

- "Secrets in stone". Kenya Past and Present. 36 (1): 67–72. 1 January 2006. doi:10.10520/AJA02578301_479 (inactive 2021-01-25).CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Ogot 1967, p. 219.

- Pitt Rivers Museum Luo Visual History. Luo Settlements and Home Structures. Available from: http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/Luo/luo/page/exhibition-settlements/index.html

- Kyle 1999, p. 11-14.

- Pitt Rivers Museum Luo Visual History. The Luo Encounter with Europeans. Available from: http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/Luo/luo/page/exhibition-encounter-europeans/index.html

- Carscallen, Arthur Asa Grandville." Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, Volume A-L. Second Revised Edition. Edited by Bobbie Jane Van Dolson and Leo R. Van Dolson. "Commentary Reference Series," Volume 10. Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1996. pp. 300–301.

- Pitt Rivers Museum Luo Visual History. Westernisation of the Luo. Available from: http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/Luo/luo/page/exhibition-european-education/index.html

- Residents Protest The Demolition Of Odera Akang’o’s Cell. Kenya News Agency. Available from: https://www.kenyanews.go.ke/residents-protest-the-demolition-of-odera-akangos-cell/ Cited 19-12-20

- Shadle, Brett L. (2002). "Patronage, Millennialism and the Serpent God Mumbo in South-West Kenya, 1912-34". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 72 (1): 29–54. doi:10.2307/3556798. hdl:10919/46785. JSTOR 3556798.

- Kyle 1999, p. 16-21.

- Murray, Nancy Uhlar (1982). "Archdeacon W. E. Owen: Missionary as Propagandist". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 15 (4): 653–670. doi:10.2307/217849. JSTOR 217849.

- Kyle 1999, p. 78.

- Kyle 1999, p. 38-43.

- MacIntyre, Ben; Orengoh, Paul (December 3, 2008). "Beatings and abuse made Barack Obamas grandfather loathe the British". The Times. London. Retrieved May 2, 2010. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/beatings-and-abuse-made-barack-obamas-grandfather-loathe-the-british-zg8qnn7jbrg

- Kyle 1999, p. 41-53.

- History of COTU. https://cotu-kenya.org/history-of-cotuk

- Kyle 1999, p. 73-74.

- Kyle 1999, p. 82-84.

- Kyle 1999, p. 119.

- Airlift to America. How Barack Obama, Sr., John F. Kennedy, Tom Mboya, and 800 East African Students Changed Their World and Ours by Tom Shachtman

- Kyle 1999, p. 70.

- Kyle 1999, p. 86-89.

- Kyle 1999, p. 100, 145, 189.

- Kyle 1999, p. 105, 119.

- Freedom and suffering. Chapter in: Kenya: Between Hope and Despair, 1963 – 2011 by Daniel Branch. Yale University Press. Nov 2011

- Kenya: The Post-Kenyatta Conundrum. CIA Intelligence Memorandum. Approved for release 2008/11/18. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85T00875R001100130082-2.pdf

- Kyle 1999, p. 200.

- Conboy, Kevin (11 February 2016). "Detention Without Trial in Kenya". Georgia Journal of International & Comparative Law. 8 (2): 441.

- “Five Opposition Leaders Seized by Kenya Police” Pasadena Independent (Pasadena, California) Fri Aug 5 1966. Page 1 Available from: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/15272844/5-opposition-leaders-seized

- Odinga, Oginga. (1977). Not yet Uhuru : the autobiography of Oginga Odinga. Heinemann. ISBN 0-435-90038-2. OCLC 264794347.

- "Dark Saturday in 1969 when Jomo’s visit to Kisumu turned bloody." Daily Nation. Wed October 24 2018. Available from: https://www.nation.co.ke/kenya/news/dark-saturday-in-1969-when-jomo-s-visit-to-kisumu-turned-bloody-101870

- Amnesty International Annual Report 1973-1974. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/POL100011974ENGLISH.PDF

- Encyclopedia Britannica. The Republic of Kenya. Kenyatta's rule. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Kenya/World-War-II-to-independence

- Kyle 1999, p. 201.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. The Republic of Kenya. Kenyatta's rule. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Kenya/World-War-II-to-independence

- Horsby, Charles (20 May 2012). "How attempted takeover of Moi Goverment [sic] by rebels flopped". Standard Digital. Retrieved 23 June 2018

- Robert Ouko 'killed in Kenya State House'. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-11962534 Cited 10-11-20

- Energy Old – Renewable Energy for Development Archived 2007-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Kenya’s Quest for a New Constitution: the Key Constitutional Moments. Available from: https://www.polity.org.za/article/kenyas-quest-for-a-new-constitution-the-key-constitutional-moments-2010-07-29 Cited 11-11-20

- Brown, Stephen (October 2001). "Authoritarian leaders and multiparty elections in Africa: How foreign donors help to keep Kenya's Daniel arap Moi in power". Third World Quarterly. 22 (5): 725–739. doi:10.1080/01436590120084575. S2CID 73647364.

- Merger shakes up Kenyan politics. BBC news. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/1878321.stm

- Kenya's entire cabinet dismissed. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4463262.stm

- UN chief calls on Kenya rivals to stop violence Archived 2008-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, The Age, 31 January 2008

- "Key points: Kenya power-sharing deal". BBC News. February 28, 2008. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- The ethnic rivalry that holds Kenya hostage. The Africa Report. Available from: https://www.theafricareport.com/734/the-ethnic-rivalry-that-holds-kenya-hostage/ Cited 18-12-20

- Kenyatta-Odinga Rivalry Spans Two Generations of Kenyan Politics. VOA news. Available from: https://www.voanews.com/africa/kenyatta-odinga-rivalry-spans-two-generations-kenyan-politics. Cited 18-12-20

- History repeats itself through Kenyatta, Odinga feud. Nation News. Available from: https://nation.africa/kenya/news/politics/history-repeats-itself-through-kenyatta-odinga-feud-11822 Cited 18-12-20

- "An African Savant: Henry Odera Oruka" article by F. Ochieng'-Odhiambo in Quest Vol. IX No. 2/Vol X No. 1 (December 1995/June 1996): 12–11.

- Reich 2018, p. 215-216.

- Grigorenko, Elena L. (2001). The organisation of Luo conceptions of intelligence : a study of implicit theories in a Kenyan village. The International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development. OCLC 842972252.

- Odenyo, Amos O. (1973). "Conquest, Clientage, and Land Law among the Luo of Kenya". Law & Society Review. 7 (4): 767–778. doi:10.2307/3052969. JSTOR 3052969.

- Ogot 1967, p. 170-175.

- Carotenuto, Matthew Paul (2006). Cultivating an African community: The Luo Union in 20th century East Africa (Thesis). ISBN 978-0-542-93443-8. ProQuest 305309018.

- https://www.tuko.co.ke/336367-struggle-power-splits-luo-council-elders-3-factions.html

- Voluntary male cut project to be rolled out in urban areas. Nation News. Available from: https://nation.africa/kenya/news/provincial/voluntary-male-cut-project-to-be-rolled-out-in-urban-areas--629514 Cited 19-12-20

- https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/nyanza/2020-08-18-unity-in-sight-as-one-luo-council-faction-quits/

- Danver, Steven L. (2013). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. M.E. Sharpe, Inc. p. 57. OCLC 1026939363.

- Johns, Timothy; Kokwaro, John O. (1991). "Food Plants of the Luo of Siaya District, Kenya". Economic Botany. 45 (1): 103–113. doi:10.1007/BF02860055. JSTOR 4255314. S2CID 38589713.

- Kustenbauder, Matthew (1 August 2009). "Believing in the Black Messiah: The Legio Maria Church in an African Christian Landscape". Nova Religio. 13 (1): 11–40. doi:10.1525/nr.2009.13.1.11.

- Jones, A.M. (1973). "Luo music and its rhythm". African Music: Journal of the African Music Society. 5 (3): 43–54. doi:10.21504/amj.v5i3.1658.

- Rateng' Ramogi Dichol Dimo II, His Majesty. "The Luo Nation-History, Origin and Culture of Luo People of Kenya". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Welbourn, F. B.; Ocholla-Ayayo, A. B. C. (1978). "Traditional Ideology and Ethics among the Southern Luo". Journal of Religion in Africa. 9 (2): 159. doi:10.2307/1581402. JSTOR 1581402.

- Traditional ideology and ethics among the southern Luo – DiVA "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-10-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Suggested reading

- Herbich, Ingrid. "The Luo." In Encyclopedia of World Cultures Supplement, C. Ember, M. Ember and I. Skoggard (eds.), pp. 189–194. New York: Macmillan Reference, 2002

- Ogot, Bethwell A., History of the Southern Luo: Volume I, Migration and Settlement, 1500–1900, (Series: Peoples of East Africa), East African Publishing House, Nairobi, 1967

- Senogazake, George, Folk Music of Kenya, ISBN 9966-855-56-4

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey, Ethnic Politics in Kenya and Nigeria, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Huntington, New York, 2001; Godfrey Mwakikagile, Kenya: Identity of A Nation, New Africa Press, Pretoria, South Africa, 2008.