Ching Shih

Ching Shih[1]:65 (Chinese: 鄭氏; lit. 'Madame Ching') (born Shih Yang (Chinese: 石陽; 1775–1844), a.k.a. Cheng I Sao (Chinese: 鄭一嫂), was a Chinese pirate leader who terrorized the China Seas during the Jiaqing Emperor period of the Qing dynasty in the early 19th century. She commanded over 1800 junks (traditional Chinese sailing ships) manned by 60,000 to 80,000 pirates[1]:71 – men, women, and occasionally children. Her ships entered into conflict with several major powers, such as the East India Company, the Portuguese Empire, and the Qing government.[2]

Ching Shih | |

|---|---|

鄭氏 | |

| |

| Born | Shih Yang (石陽) 1775 |

| Died | 1844 (aged 68–69) |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Occupation | Pirate and former prostitute |

| Known for | Well known female Chinese pirate |

| Criminal charge(s) | Piracy |

| Criminal penalty | Death penalty |

| Criminal status | Amnestied |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Piratical career | |

| Nickname | Shih Heang Koo (石香姑) |

| Other names | Ching I Sao (鄭一嫂) Ching Shih Shih (鄭石氏) |

| Type | Pirate |

| Allegiance | Red Flag Fleet |

| Years active | 1801–1810 |

| Rank | Fleet commander |

| Base of operations | South China Sea |

| Commands | Red Flag Fleet (300 ships of 20,000–40,000 pirates) |

| Battles/wars | Battle of the Tiger's Mouth Naval Battle of Chek Lap Kok |

| Later work | Gambling house owner at Guangzhou gambling house and brothel owner, salt trader at Macao Military advisor |

| Ching Shih | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ching Shih | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭氏 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑氏 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | widow of Cheng | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Cheng I Sao | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭一嫂 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑一嫂 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | wife of Cheng I | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Shih Yang (birth name) | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 石陽 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 石阳 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Shih Heang Koo (former nickname) | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 石香姑 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Ching Shih and her crew's exploits have since been featured in numerous books, novels, video games, and films about pirates and their way of life in China as well as in a global context. Based on her influence and achievements as a pirate, which included commanding a vast fleet of around 1,500-1,800 ships manned by 80,000 sailors during her peak, she is accepted by many as being the most successful pirate in history.[3][4][5][6][7]

Early life

Ching Shih was born Shih Yang (石陽) in 1775 in the province of Guangdong. She was a Cantonese prostitute or madame who worked in a floating brothel (花船) in Canton. In 1801, she married Cheng I, a well-known pirate.

Marriage to Cheng I

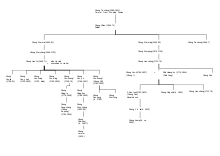

Cheng I was from a family of well-known pirates whose roots traced back to the Ming dynasty. Sources differ on Cheng I's motivation for marriage: some argue that he became infatuated with Shih Heang Koo, while others argue that the union was purely a business move intended to consolidate power. Either way, Shih Heang Koo is said to have agreed to lend her powers of intrigue, as it were, to her husband's endeavors by formal contract, which granted her a 50% control and share of all profits. Following their marriage, Shih "participated fully in her husband's piracy" and became known as Cheng I Sao (鄭一嫂; 'wife of Cheng I'). They adopted Cheung Po as their step-son, acknowledging him as Cheng's sole legal heir. Cheng also bore two more sons: Cheng Ying Shih (鄭英石) and Cheng Heung Shih (鄭雄石). Cheng I used his reputation and naval strength to bind former rivaling Cantonese pirate fleets into a unified alliance. Cheng I and Ching Shih formed a massive coalition from unifying small groups of pirates into a federation of 70,000 men and 400 junk ships. Their coalition consisted of six fleets known by the colors of blue, red, green, black, white, and yellow.[8] By 1804, this coalition was a formidable force, and one of the most powerful pirate fleets in all of China; by this time they were known as the Red Flag Fleet.

Ascension to leadership

On 16 November 1807, Cheng I died in Vietnam at the age of 39.[9] Ching Shih immediately began maneuvering her way into his leadership position. She took control of her late husband's pirate fleet and by 1809, commanded over 800 large junks and 1,000 smaller ships. She also commanded over 70,000 men and women in her pirate crew. She commanded the Red Flag Fleet and controlled South China's seas. She earned the trust of her lieutenants by sharing her power with them. With these men under her, their fleet collected money, raided government camps and ships, sailed into Chinese river towns and coastal villages to extort them, and quickly grew in power. Madame Ching and her crew escaped every attempt by the government to get her band of pirates under control and were eventually offered amnesty for her crimes and offered her pirates the opportunity to the Imperial Chinese Navy.[10] She started to cultivate personal relationships to try and get rivals to recognize her status and solidify her authority. Ching Shih acted quickly to solidify the partnership with her adopted son Cheung Po by entering into a sexual relationship.[11] In order to stop her rivals before open conflict erupted, she sought the support of the most powerful members of her husband's family: his nephew Ching Pao-yang and his cousin's son Ching Ch'i. Then she drew on the coalition formed by her husband by building upon some of the fleet captains' existing loyalties to her husband and making herself essential to the remaining captains.[1]:71

In order to remain in control of the federation, Ching Shih seduced her step-son Cheung Po. She chose him due to his loyalties and ties to Cheng I, thus securing a leader who would be loyal to her and accepted by the lower ranking pirates.[8]

Code of laws

Once she held the fleet's leadership position, Ching Shih started the task of uniting the fleet by issuing a code of laws.[12]:28 The Neumann translation of The History of Pirates Who Infested the China Sea claims that it was Cheung Po Tsai that issued the code.[13] Yuan Yung-lun says that Cheung issued his own code of three regulations, called san-t'iao, for his own fleet, but these are not known to exist in a written form.[9] The code was very strict and according to Richard Glasspoole, strictly enforced.[14]

- Anyone giving their own orders (ones that didn't come down from Ching Shih) or disobeying those of a superior was beheaded on the spot.

- No one was to steal from the public fund or any villagers that supplied the pirates.[9]

- All goods taken as booty had to be presented for group inspection. The booty was registered by a purser and then distributed by the fleet leader. The original seizer received 20% and the rest was placed into the public fund.

- Actual money was turned over to the squadron leader, who only gave a small amount back to the seizer, so the rest could be used to purchase supplies for unsuccessful ships.[9][12]:39 According to Philip Maughan, the punishment for a first-time offense of withholding booty was severe whipping of the back. Large amounts of withheld treasure or subsequent offenses carried the death penalty.[12]:29

Ching Shih's code had special rules for female captives. Standard practice was to release women, but J.L. Turner witnessed differently. Usually, the pirates made their most beautiful captives their concubines or wives. If a pirate took a wife he had to be faithful to her.[15] The ones deemed unattractive were released and any remaining were ransomed. Pirates that raped female captives were put to death. If pirates had consensual sex with captives, the pirate was beheaded and the woman he was with had cannonballs attached to her legs and was thrown over the side of the boat.[9][12]:29[15]

Violations of other parts of the code were punished with flogging, clapping in irons, or quartering. Deserters or those who had left without official permission had their ears chopped off and then paraded around their squadron. Glasspoole concluded that the code "gave rise to a force that was intrepid in attack, desperate in defense, and unyielding even when outnumbered."[14]

Pirate career

The fleet under her command established hegemony over many coastal villages, in some cases even imposing levies and taxes on settlements. According to Robert Antony, Ching Shih "robbed towns, markets, and villages, from Macau to Canton."[16] In one coastal village, the Sanshan village, they beheaded 80 men and abducted their women and children and held them for ransom until they were sold in slavery.[17]

In January 1808, the Chinese government tried to destroy her fleet in a series of fierce battles. However, Ching Shih inflicted several defeats on the Chinese navy, capturing and commandeering several of their ships. The government had to revert to using fishing vessels for battle.[18]

At the same time that the government was attacking her, Ching Shih faced a larger threat in the form of other pirate fleets. One, in particular, was O-po-tae, a former allied-pirate who began working with the Qing government, which forced them to retreat from the coast.

For years, the Red Flag Fleet under Ching Shih's rule could not be defeated, neither by Chinese government officials nor by European bounty hunters hired by the Qing government.[19][20] She captured the East India Company merchantman The Marquis of Ely in 1809. The ship was crewed by Captain Richard Glasspoole and seven sailors, all of whom were eventually released. Glasspoole later wrote about his experience in Ching Shih's captivity.[13]

In September and November 1809, Ching Shih and Cheung Po Tsai fleet suffered a series of defeats at the hands of the Portuguese Navy at the Battle of the Tiger's Mouth, eventually coming to the realization there was no way they would be able to hold out forever. In their final battle at Chek Lap Kok in 1810, they surrendered to the Portuguese Navy on 21 January and later accepted an amnesty offered by the Qing Imperial government to all pirates who agreed to surrender, ending their career and allowed to keep the loot that same year.[21] This amnesty allowed only 60 pirates to be banished, 151 to be exiled, and only 126 to be put to death out of her whole fleet of 17,318 pirates.[17] The remaining pirates only had to surrender their weapons. Cheung Po Tsai changed back to his former name and was repatriated to the Qing Dynasty government. He became a captain in the Qing's Guangdong navy. That is one story. However, the Portuguese version does not match in terms of dates or much else two other sources, the Chinese narrative of Yuan Yonglun, the Jinghai Fenji[22] that was translated and published in English in 1831[23] or Richard Glasspoole's narrative of his capture, made as an official report to the East India Company, which appears as an appendix to Neumann's translation and various other contemporary and later sources.[24] From these two sources it seems clear that the Portuguese narrative, not published until twenty years later[25] has significant errors.

Late life and death

Upon being pardoned for her life as a pirate, Ching Shih negotiated for Cheung Po to retain several ships, including approximately 120 to be used for employment on the salt trade. She also arranged for Cheung Po and other pirates in the fleets to be given positions in the Chinese bureaucracy.[8]

Ching Shih also requested that the government officially recognize her as the wife of Cheung Po. Despite the restrictions against widows remarrying, her request was granted as the wife of a government official.[8] In 1813, Ching Shih gave birth to a son, Cheung Yu Lin. She would later have a daughter who was born at an unknown date.

After Cheung Po died at sea in 1822, Ching Shih moved the family to Macau and opened a gambling house.[26] She was also involved in the salt trade there.[27]

In her later years, she served as an advisor to Lin Zexu during the First Opium War (1839-1842).[28]

In 1844, she died in bed surrounded by her family in Macau, at the age of 69.[26]

Cultural references

A semi-fictionalized account of Ching Shih's piracy appeared in Jorge Luis Borges's short story The Widow Ching, Lady Pirate (part of A Universal History of Infamy (1935)), where she is described as "a lady pirate who operated in Asian waters, all the way from the Yellow Sea to the rivers of the Annam coast", and who, after surrendering to the imperial forces, is pardoned and allowed to live the rest of her life as an opium smuggler. Borges acknowledged the 1932 book The History of Piracy, by Philip Gosse (grandson of the naturalist Philip Henry Gosse), as the source of the tale.[29]

In chapter 15 of Codename: Sailor V, a manga created by Naoko Takeuchi, Sailor V transforms temporarily into Ching Shih.

In 2003, Ermanno Olmi made a film, Singing Behind Screens, loosely based on Borges's retelling, though rights problems prevented the Argentine writer from appearing in the credits.[30][31]

Afterlife, a 2006 OEL graphic novel, depicts Ching Shih as a guardian who fights demons to protect the denizens of the underworld.

In The Wake of the Lorelei Lee, book 8 of L.A. Meyer's Bloody Jack series, Jacky is captured by Ching Shih and so impresses her that the pirate bestows her with a tattoo of a dragon on the back of her neck to indicate she is under Shih's protection.

A character loosely based on Ching Shih appears in the 2007 film Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End. Played by Takayo Fischer Mistress Ching is portrayed as one of the 9 Pirate Lords of the Brethren Court and the powerful leader of the pirate confederation of China. The character also appears in 3 tie-in books, Rising in the East, Day of the Shadow, and The Price of Freedom.

Another character possibly based on Ching Shih, appears in the 2020 game Genshin Impact, created by miHoYo. Known as Captain of the Crux, Beidou is described as "a trusted, unbound and forthright leader".

Puppetmongers Theatre of Toronto, Canada, mounted 2 different productions based on Ching Shih's life. The first was a co-production with the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, directed by Jon Ludwig in 2000, and the second version, directed by Mark Cassidy played at Toronto's Tarragon Theatre Extra Space in 2002.

In the 2015 Hong Kong television drama Captain of Destiny, Maggie Shiu plays a character who's based on Ching Shih.

Red Flag, a limited series which centers on Ching Shih, starring Maggie Q and Francois Arnaud, was scheduled to start filming in the fall of 2014 in Malaysia.[32]

On 19 March 2018, a character who references the real-life Ching Shih, named "Madame Shih" was added to the MMORPG Runescape, debuting in a pirate-themed quest titled "Pieces of Hate". She goes on to feature in another quest, released on 25 February 2019, titled "Curse of the Black Stone". In both quests, she was captured but eventually escapes with help from the player, possibly referencing Ching Shih's knack for getting out of all sorts of dangerous situations.[33]

In 2020, Angela Eiter did the first ascent of the mountain climbing route Madame Ching (which she named after Ching Shih) in Imst, Austria.[34][35]

See also

References

- Murray, Dian (1987). Pirates of the South China Coast, 1790–1810. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1376-4.

- Lily Xiao Hong Lee, A. D. Stefanowska, Clara Wing-chung Ho, 2003, 387 pages

- Banerji, Urvija (6 April 2016). "The Chinese Female Pirate Who Commanded 80,000 Outlaws". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Mrs. Cheng: The Most Successful Pirate in History". HowStuffWorks. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Most successful pirate was beautiful and tough". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "History's greatest woman pirate becomes a Hong Kong children's story". South China Morning Post. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "The Pirate Ching Shih « The Global Dispatches". Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Murray, Dian (1981). "One Woman's Rise to Power: Cheng I's Wife and the Pirates". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 8 (3): 147–161. ISSN 0315-7997.

- Yuan Yung-lun. Ching hai-fen chi (Record of the Pacification of the Pirates).

- "PIRATE QUEEN: A STORY OF ZHENG YI SAO." Kirkus Reviews LXXXVIII, no. 1 (1 Jan 2020). ProQuest 2331022871

- Lu K'un, Ch'eng, Kwang-tung hai-fang hui-lan (An Examination of Kwangtung's Sea Defense)

- Maughan, Philip (1812). "An Account of the Ladrones Who Infested the Coast of China". Further Statement of the Ladrones on the Coast of China. London: Lane, Darling.

- Murray, Dian (2001). "Cheng I Sao in Fact and Fiction". In Pennell, C.R. (ed.). Bandits at Sea: A Pirates Reader. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-0-8147-6679-8.

- Glasspoole, Richard (1812). "Substance of Mr. Glasspoole's Relation, Upon His Return to England, Respecting the Ladrones" (PDF). Further statement of the ladrones on the coast of China: intended as a continuation of the accounts published by Mr. Dalrymple. Printed by Lane, Darling. pp. 44–45.

- Turner, J. (c. 1809). Account of the Captivity of J. J. Turner, Chief Mate of the Ship Tay, Amongst the Ladrones. London: T. Tegg. p. 71.

- Antony, Robert (2003). Like Froth Floating on the Sea: The world of pirates and seafarers in Late Imperial South China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-1-55729-078-6.

- Vallar, Cindy. "Pirates & Privateers: The History of Maritime Piracy – Cheng I Sao". www.cindyvallar.com. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Ossian, Rob. "Cheng I Sao". thepirateking.com. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- "Woman Becomes One of World's Most Powerful Pirates ⋆ History Channel". 20 June 2016.

- Gail Selinger; W. Thomas Smith, Jr. (2006). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Pirates. Alpha Books. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-59257-376-9.

- Andrea J. Buchanan, Miriam Peskowitz-2007-279-page

- Yuan, Yonglun (1830). Jinghai Fenji. Guangzhou.

- Neumann, Charles Friedrich (1831). History of the pirates who infested the China Sea from 1807 to 1810. London: Oriental Translation Fund.

- Further statement of the ladrones on the coast of China: intended as a continuation of the accounts published by Mr. Dalrymple. London: Lane, Darling & Co. 1812.

- Andreade, Jose Ignacio (1835). Memorie dos feitoes Macaenses contra os piratas da China: e da entrada violenta does Inglezes na cidade de Macao. Lisbon: na Typografia Lisbonense.

- Koerth-Baker, Maggie (28 August 2007). "Most successful pirate was beautiful and tough". CNN. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- 104098. "盘点古代女富豪:寡妇清身家约白银8亿万两--文史--人民网". history.people.com.cn. Retrieved 1 November 2018.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "中国历史上最强女海盗:曾只身俘获英国军舰-搜狐军事频道". mil.sohu.com. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Borges, Jorge Luis (1972). A Universal History of Infamy. Dutton.

- Cantando dietro i paraventi at IMDb

- Weissberg, Jay (23 October 2003). "Singing Behind Screens". Variety.

- "Francois Arnaud To Co-Star in Limited Series 'Red Flag'". Deadline Hollywood. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Runescape Wiki-Madame Shih

- http://www.climbing.com/.amp/news/angy-eiter-completes-5-15b-first-ascent-story-photo-gallery/

- 🖉"NEWSFLASH: 9b First Ascent for Angela Eiter". www.ukclimbing.com.