William Kidd

William Kidd, also known as Captain William Kidd or simply Captain Kidd (c. 1655 – 23 May 1701),[1] was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians, for example Sir Cornelius Neale Dalton, deem his piratical reputation unjust.[2]

William Kidd | |

|---|---|

Portrait by James Thornhill | |

| Born | c. 1655 Greenock, Scotland |

| Died | 23 May 1701 (aged 47) Wapping, England |

| Relatives | Shea Dauphinée, Michael Dauphinée, James Dauphinée |

| Piratical career | |

| Type | Pirate / Privateer |

| Allegiance | |

| Commands | Blessed William Adventure Galley |

Biography

Early life and education

Kidd was born in Dundee,[3] Scotland. Greenock was given as his place of birth (although some say it was Dundee, and others say Belfast),[4] and his age as 41 in testimony under oath at the High Court of the Admiralty in October 1694 or 1695.[5] A local society supported the family financially after the death of the father.[6] The myth that his "father was thought to have been a Church of Scotland minister" has been discounted, insofar as there is no mention of the name in comprehensive Church of Scotland records for the period. Others still hold the contrary view.[7][8]

Early voyages

Kidd later settled in the newly anglicized New York City,[9] where he befriended many prominent colonial citizens, including three governors.[10] Some published information suggests that he was a seaman's apprentice on a pirate ship during this time, before partaking in his more famous seagoing exploits.

By 1689, Kidd was a member of a French–English pirate crew sailing the Caribbean under Captain Jean Fantin.[11] During one of their voyages, Kidd and other crew members mutinied, ousting the captain and sailing to the British colony of Nevis.[12] There they renamed the ship Blessed William, and Kidd became captain either as a result of election by the ship's crew, or by appointment of Christopher Codrington, governor of the island of Nevis.[13] Captain Kidd, an experienced leader and sailor by that time, and the Blessed William became part of Codrington's small fleet assembled to defend Nevis from the French, with whom the English were at war.[14][15] The governor did not pay the sailors for their defensive services, telling them instead to take their pay from the French. Kidd and his men attacked the French island of Marie-Galante, destroying its only town and looting the area, and gathering for themselves around 2,000 pounds sterling. Later, during the War of the Grand Alliance, on commissions from the provinces of New York and Massachusetts Bay, Kidd captured an enemy privateer off the New England coast.[16] Shortly afterwards, he was awarded £150 for successful privateering in the Caribbean, and one year later, Captain Robert Culliford, a notorious pirate, stole Kidd's ship while he was ashore at Antigua in the West Indies. In 1695, William III of England appointed Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont, governor in place of the corrupt Benjamin Fletcher, who was known for accepting bribes to allow illegal trading of pirate loot.[17] In New York City, Kidd was active in the building of Trinity Church, New York.[18][19]

On 16 May 1691, Kidd married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort,[20] an English woman in her early twenties, who had already been twice widowed and was one of the wealthiest women in New York, largely because of her inheritance from her first husband.[21]

Preparing his expedition

On 11 December 1695, Bellomont was governing New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, and he asked the "trusty and well beloved Captain Kidd"[22] to attack Thomas Tew, John Ireland, Thomas Wake, William Maze, and all others who associated themselves with pirates, along with any enemy French ships. It would have been viewed as disloyalty to the crown to turn down this request, carrying much social stigma, making it difficult for Kidd to say no. The request preceded the voyage which established Kidd's reputation as a pirate and marked his image in history and folklore.

Four-fifths of the cost for the venture was paid for by noble lords, who were among the most powerful men in England: the Earl of Orford, the Baron of Romney, the Duke of Shrewsbury, and Sir John Somers. Kidd was presented with a letter of marque, signed personally by King William III of England. This letter reserved 10% of the loot for the Crown, and Henry Gilbert's The Book of Pirates suggests that the King may have fronted some of the money for the voyage himself. Kidd and his acquaintance Colonel Robert Livingston orchestrated the whole plan; they sought additional funding from a merchant named Sir Richard Blackham.[23] Kidd also had to sell his ship Antigua to raise funds.

The new ship, Adventure Galley,[24] was well suited to the task of catching pirates, weighing over 284 tons burthen and equipped with 34 cannon, oars, and 150 men. The oars were a key advantage, as they enabled Adventure Galley to manoeuvre in a battle when the winds had calmed and other ships were dead in the water. Kidd took pride in personally selecting the crew, choosing only those whom he deemed to be the best and most loyal officers.

As the Adventure Galley sailed down the Thames, Kidd unaccountably failed to salute a Navy yacht at Greenwich, as custom dictated. The Navy yacht then fired a shot to make him show respect, and Kidd's crew responded with an astounding display of impudence – by turning and slapping their backsides in [disdain].[25]

Because of Kidd's refusal to salute, the Navy vessel's captain retaliated by pressing much of Kidd's crew into naval service, despite rampant protests. Thus short-handed, Kidd sailed for New York City, capturing a French vessel en route (which was legal under the terms of his commission). To make up for the lack of officers, Kidd picked up replacement crew in New York, the vast majority of whom were known and hardened criminals, some undoubtedly former pirates.

Among Kidd's officers was his quartermaster Hendrick van der Heul. The quartermaster was considered "second in command" to the captain in pirate culture of this era. It is not clear, however, if Van der Heul exercised this degree of responsibility because Kidd was nominally a privateer. Van der Heul is also noteworthy because he may have been African or of African descent. A contemporary source describes him as a "small black Man". If Van der Heul was indeed of African ancestry, this fact would make him the highest-ranking black pirate so far identified. Van der Heul went on to become a master's mate on a merchant vessel and was never convicted of piracy.

Hunting for pirates

In September 1696, Kidd weighed anchor and set course for the Cape of Good Hope. A third of his crew died on the Comoros due to an outbreak of cholera, the brand-new ship developed many leaks, and he failed to find the pirates whom he expected to encounter off Madagascar.

As it became obvious that his ambitious enterprise was failing, Kidd became desperate to cover its costs. But, once again, he failed to attack several ships when given a chance, including a Dutchman and a New York privateer. Some of the crew deserted Kidd the next time that Adventure Galley anchored offshore, and those who decided to stay on made constant open threats of mutiny.

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. Kidd's gunner William Moore was on deck sharpening a chisel when a Dutch ship appeared. Moore urged Kidd to attack the Dutchman, an act not only piratical but also certain to anger Dutch-born King William. Kidd refused, calling Moore a lousy dog. Moore retorted, "If I am a lousy dog, you have made me so; you have brought me to ruin and many more." Kidd snatched up and heaved an ironbound bucket at Moore. Moore fell to the deck with a fractured skull and died the following day.[26]

Seventeenth-century English admiralty law allowed captains great leeway in using violence against their crew, but outright murder was not permitted. Yet Kidd seemed unconcerned, later explaining to his surgeon that he had "good friends in England, that will bring me off for that".

Accusations of piracy

Acts of savagery on Kidd's part were reported by escaped prisoners, who told stories of being hoisted up by the arms and "drubbed" (thrashed) with a drawn cutlass. On one occasion, crew members ransacked the trading ship Mary and tortured several of its crew members while Kidd and the other captain, Thomas Parker, conversed privately in Kidd's cabin. When Kidd found out what had happened, he was outraged and forced his men to return most of the stolen property.

Kidd was declared a pirate very early in his voyage by a Royal Navy officer, to whom he had promised "thirty men or so".[22] Kidd sailed away during the night to preserve his crew, rather than subject them to Royal Navy impressment.[27]

On 30 January 1698, Kidd raised French colours and took his greatest prize, the 400-ton Quedagh Merchant,[28][29] an Indian ship hired by Armenian merchants that was loaded with satins, muslins, gold, silver, an incredible variety of East Indian merchandise, as well as extremely valuable silks. The captain of Quedagh Merchant was an Englishman named Wright, who had purchased passes from the French East India Company promising him the protection of the French Crown. After realising the captain of the taken vessel was an Englishman, Kidd tried to persuade his crew to return the ship to its owners, but they refused, claiming that their prey was perfectly legal, as Kidd was commissioned to take French ships, and that an Armenian ship counted as French if it had French passes. In an attempt to maintain his tenuous control over his crew, Kidd relented and kept the prize. When this news reached England, it confirmed Kidd's reputation as a pirate, and various naval commanders were ordered to "pursue and seize the said Kidd and his accomplices" for the "notorious piracies" they had committed.[30]

Kidd kept the French sea passes of the Quedagh Merchant, as well as the vessel itself. While the passes were at best a dubious defence of his capture, British admiralty and vice-admiralty courts (especially in North America) heretofore had often winked at privateers' excesses into piracy, and Kidd may have been hoping that the passes would provide the legal fig leaf that would allow him to keep Quedagh Merchant and her cargo. Renaming the seized merchantman Adventure Prize, he set sail for Madagascar.

On 1 April 1698, Kidd reached Madagascar. After meeting privately with trader Tempest Rogers (who would later be accused of trading and selling Kidd's looted East India goods),[31] he found the first pirate of his voyage, Robert Culliford (the same man who had stolen Kidd's ship years before) and his crew aboard Mocha Frigate. Two contradictory accounts exist of how Kidd reacted to his encounter with Culliford. According to The General History of the Pirates, published more than 25 years after the event by an author whose identity remains in dispute, Kidd made peaceful overtures to Culliford: he "drank their Captain's health", swearing that "he was in every respect their Brother", and gave Culliford "a Present of an Anchor and some Guns".[32] This account appears to be based on the testimony of Kidd's crewmen Joseph Palmer and Robert Bradinham at his trial. The other version was presented by Richard Zacks in his 2002 book The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. According to Zacks, Kidd was unaware that Culliford had only about 20 crew with him, and felt ill-manned and ill-equipped to take Mocha Frigate until his two prize ships and crews arrived, so he decided not to molest Culliford until these reinforcements came. After Adventure Prize and Rouparelle came in, Kidd ordered his crew to attack Culliford's Mocha Frigate. However, his crew, despite their previous eagerness to seize any available prize, refused to attack Culliford and threatened instead to shoot Kidd. Zacks does not refer to any source for his version of events.[33]

Both accounts agree that most of Kidd's men now abandoned him for Culliford. Only 13 remained with Adventure Galley. Deciding to return home, Kidd left the Adventure Galley behind, ordering her to be burnt because she had become worm-eaten and leaky. Before burning the ship, he was able to salvage every last scrap of metal, such as hinges. With the loyal remnant of his crew, he returned to the Caribbean aboard the Adventure Prize. Some of his crew later returned to America on their own as passengers aboard Giles Shelley's ship Nassau.[34]

Trial and execution

Prior to returning to New York City, Kidd knew that he was a wanted pirate and that several English men-of-war were searching for him. Realizing that Adventure Prize was a marked vessel, he cached it in the Caribbean Sea, sold off his remaining plundered goods through pirate and fence William Burke,[35] and continued toward New York aboard a sloop. He deposited some of his treasure on Gardiners Island, hoping to use his knowledge of its location as a bargaining tool.[36] Kidd found himself in Oyster Bay, as a way of avoiding his mutinous crew who gathered in New York. In order to avoid them, Kidd sailed 120 nautical miles (220 km; 140 mi) around the eastern tip of Long Island, and then doubled back 90 nautical miles (170 km; 100 mi) along the Sound to Oyster Bay. He felt this was a safer passage than the highly trafficked Narrows between Staten Island and Brooklyn.[37]

Bellomont (an investor) was away in Boston, Massachusetts. Aware of the accusations against Kidd, Bellomont was justifiably afraid of being implicated in piracy himself and knew that presenting Kidd to England in chains was his best chance to save himself. He lured Kidd into Boston with false promises of clemency,[38] then ordered him arrested on 6 July 1699. Kidd was placed in Stone Prison, spending most of the time in solitary confinement. His wife, Sarah, was also imprisoned. The conditions of Kidd's imprisonment were extremely harsh, and appear to have driven him at least temporarily insane. By then, Bellomont had turned against Kidd and other pirates, writing that the inhabitants of Long Island were "a lawless and unruly people" protecting pirates who had "settled among them".[39]

After over a year, Kidd was sent to England for questioning by the Parliament of England. The new Tory ministry hoped to use Kidd as a tool to discredit the Whigs who had backed him, but Kidd refused to name names, naively confident his patrons would reward his loyalty by interceding on his behalf. There is speculation that he probably would have been spared had he talked. Finding Kidd politically useless, the Tory leaders sent him to stand trial before the High Court of Admiralty in London, for the charges of piracy on high seas and the murder of William Moore. Whilst awaiting trial, Kidd was confined in the infamous Newgate Prison, and wrote several letters to King William requesting clemency.

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defence.[40] He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy) and sentenced to death. He was hanged in a public execution on 23 May 1701, at Execution Dock, Wapping, in London.[16] He was hanged twice. On the first attempt, the hangman's rope broke and Kidd survived. Although some in the crowd called for Kidd's release, claiming the breaking of the rope was a sign from God, Kidd was hanged again minutes later, this time successfully. His body was gibbeted over the River Thames at Tilbury Point – as a warning to future would-be pirates – for three years.[41]

Kidd's associates Richard Barleycorn, Robert Lamley, William Jenkins, Gabriel Loffe, Able Owens, and Hugh Parrot were also convicted, but pardoned just prior to hanging at Execution Dock.

Kidd's Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early twentieth century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building.[42] These passes call the extent of Kidd's guilt into question. Along with the papers, many goods were brought from the ships and soon auctioned off as "pirate plunder". They were never mentioned in the trial.

As to the accusations of murdering Moore, on this he was mostly sunk on the testimony of the two former crew members, Palmer and Bradinham, who testified against him in exchange for pardons. A deposition Palmer gave, when he was captured in Rhode Island two years earlier, contradicted his testimony and may have supported Kidd's assertions, but Kidd was unable to obtain the deposition.

A broadside song, "Captain Kidd's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament", was printed shortly after his execution and popularised the common belief that Kidd had confessed to the charges.[43]

_for_Allen_%2526_Ginter_Cigarettes_MET_DP835020.jpg.webp)

Mythology and legend

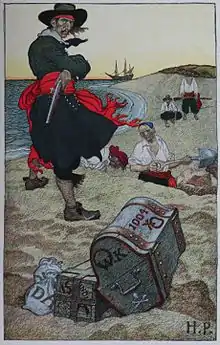

The belief that Kidd had left buried treasure contributed considerably to the growth of his legend. The 1701 broadside song "Captain Kid's Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament" lists "Two hundred bars of gold, and rix dollars manifold, we seized uncontrolled".[43][44] This belief made its contributions to literature in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug"; Washington Irving's "The Devil and Tom Walker"; Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island and Nelson DeMille's Plum Island. It also gave impetus to the constant treasure hunts conducted on Oak Island in Nova Scotia; in Suffolk County, Long Island in New York where Gardiner's Island is located; Charles Island in Milford, Connecticut; the Thimble Islands in Connecticut; Cockenoe Island in Westport, Connecticut;[45] and on the island of Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy.

Captain Kidd did bury a small cache of treasure on Gardiners Island in a spot known as Cherry Tree Field; however, it was removed by Governor Bellomont and sent to England to be used as evidence against Kidd.[46][47]

Some time during the 1690s Kidd visited Block Island, where he was supplied by Mrs. Mercy (Sands) Raymond, daughter of the mariner James Sands. The story has it that, for her hospitality, Mrs. Raymond was bid to hold out her apron, into which Kidd threw gold and jewels until it was full. After her husband Joshua Raymond died, Mercy moved with her family to northern New London, Connecticut (later Montville), where she bought much land. The Raymond family was thus said to have been "enriched by the apron".[48]

On Grand Manan in the Bay of Fundy, as early as 1875, reference was made to searches on the west side of the island for treasure allegedly buried by Kidd during his time as a privateer.[49] For nearly 200 years, this remote area of the island has been called "Money Cove".

In 1983, Cork Graham and Richard Knight went looking for Captain Kidd's buried treasure off the Vietnamese island of Phú Quốc. Knight and Graham were caught, convicted of illegally landing on Vietnamese territory, and assessed each a $10,000 fine. They were imprisoned for 11 months until they paid the fine.[50]

Quedagh Merchant found

For years, people and treasure hunters have tried to locate Quedagh Merchant.[51] It was reported on 13 December 2007 that "wreckage of a pirate ship abandoned by Captain Kidd in the 17th century has been found by divers in shallow waters off the Dominican Republic." The waters in which the ship was found were less than ten feet deep and were only 70 feet (21 m) off Catalina Island, just to the south of La Romana on the Dominican coast. The ship is believed to be "the remains of Quedagh Merchant".[52][53] Charles Beeker, the director of Academic Diving and Underwater Science Programs in Indiana University (Bloomington)'s School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, was one of the experts leading the Indiana University diving team. He said that it was "remarkable that the wreck has remained undiscovered all these years given its location," and given that the ship has been the subject of so many prior failed searches.[54] Captain Kidd's cannon, an artifact from the shipwreck, was added to a permanent exhibit at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis in 2011.[55]

False find

In May 2015, a 50-kilogram (110 lb) ingot expected to be silver was found in a wreck off the coast of Île Sainte-Marie in Madagascar by a team led by marine archaeologist Barry Clifford, and was believed to be part of Captain Kidd's treasure.[56][57][58] Clifford handed the booty to Hery Rajaonarimampianina, President of Madagascar.[59][60] However, in July 2015, a UNESCO scientific and technical advisory body revealed that the ingot consisted of 95% lead, and speculated that the wreck in question might be a broken part of the Sainte-Marie port constructions.[61]

Portrayals in popular culture

Edgar Allan Poe uses the legend of Kidd's buried treasure in his seminal detective story The Gold Bug.

Charles Laughton played Kidd twice on film, first in 1945 in Captain Kidd, then in 1952 in Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd.

Kidd is mentioned in the 1945 song "Captain Kidd" by singer Ella Mae Morse with Billy May and his orchestra.[62]

Kidd is also name-checked in the song The Land of Make Believe by Bucks Fizz, which was a number-one hit in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium and Ireland in 1982. The lyric is, "Captain Kidd's on the sand, With the treasure close at hand."

John Crawford played Kidd in the 1953 Columbia film serial The Great Adventures of Captain Kidd.

The most recent film portrayal was by Love Nystrom in the 2006 mini-series Blackbeard.

Captain Kidd is mentioned in Bob Dylan's song Bob Dylan's 115th Dream from his fifth album Bringing It All Back Home.

Captain Kidd appears in Persona 5, as one of the eponymous Personas belonging to Ryuji Sakamoto. The game's theme is about outcasts/outlaws, as well as rebellion against the established order/society, and portrays several individuals (mostly from fiction) that fit this theme, such as Arsène Lupin, Pope Joan and Ishikawa Goemon.

Captain Kidd appears in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

The 1957 children's book Captain Kidd's Cat by Robert Lawson is a largely fictionalized account of Kidd's last voyage, trial and execution, told from the point of view of his loyal ship's cat. The book portrays Kidd as an innocent privateer who was framed by corrupt officials as a scapegoat for their own crimes.

The song "Ballad of William Kidd" by the heavy metal band Running Wild is based on Kidd's life, particularly the events surrounding his trial and execution.

A version of "Ballad of William Kidd" is sung by Commander Klaes Ashford in Seasons 3 and 4 of "The Expanse"

"The Ballad of William Kidd" is performed by Blackbeard's Tea Party, making reference to his life throughout the song.

Doraemon: Nobita's Great Adventure in the South Seas portrays a highly fictionalized version of Captain Kidd as a pirate in the Pacific with more of an American accent than a Scottish one who comes across the Doraemon and his friends that were caught in a time distortion. The combined group finds an island with secret treasure and is being used by a business from the future for his own benefit. Eventually, the businessman is captured by the Time Patrol and Kidd continues his voyage.

The character of Ogin in the anime Girls und Panzer models herself heavily on Kidd, particularly with regard to her personality and leadership style. She is the commander of a British Mark IV tank in "Das Finale".

The band Scissorfight had a song called "The Gibbeted Captain Kidd" on their 1998 album Balls Deep.

In the manga and anime series One Piece, there is a character named Eustass "Captain" Kid, whose name and epithet are inspired by the real-life Captain Kidd.

Four missions in Assassin's Creed III involve finding map pieces that Captain Kidd had given to four of his crew members for safekeeping. Finding all four pieces would reveal the location of Kidd's treasure, which in the Assassin's Creed series is a Piece of Eden that gives the player the ability to repel bullets.

Captain Kidd inspired the creation of a pirate character by the same name in various video games published by SNK. The character makes appearances in the games World Heroes 2, World Heroes 2 Jet, World Heroes Perfect, and SNK vs. Capcom: Card Fighters Clash.

See also

- Joseph Bradish, a pirate who sailed in Kidd's company[63]

- George Dew, buccaneer, pirate, and privateer who briefly sailed alongside Kidd in 1691 near the Piscataqua River.[64]

- Captain Kidd's Cannon

- Gardiners Island

- Oak Island

- Treasure Island

References and notes

- Johnson, Ben. "Captain William Kidd". Historic UK. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "Execution of Captain Kidd | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Captain William Kidd". Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- "William Kidd: Biography on Undiscovered Scotland". www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Laing, Aislinn (7 May 2015). "Captain William Kidd: privateer or pirate?". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Courtly Lives – The Kidd Family". www.angelfire.com. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Pirates: William Kidd". Genealogy & Family History Achievements Heraldry and Research. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Hawkins, Paul (2002). "Captain William Kidd Web Site: History". Archived from the original (self-published historical site) on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "Captain Kidd in New York City | Boroughs of the Dead". Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Boys, Bowery (27 January 2010). "Captain Kidd and his swanky New York waterfront home". The Bowery Boys: New York City History. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Jean Fantin, St. Kitts, 1689 LIMITED EDITION". Ferminiatures.com. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Zacks, Richard (2003). The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. New York: Hachette Books. ISBN 9781401398187. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Selwood, Dominic (23 May 2017). "On this day in 1701: Pirate of the Caribbean, William 'Captain' Kidd, meets his end at Execution Dock". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Hubbard, Vincent (2002). A History of St. Kitts. Macmillan Caribbean. p. 52. ISBN 9780333747605.

- Hubbard, Vincent (2002). Swords, Ships & Sugar. Corvallis: Premiere Editions International, Inc. pp. 104–105. ISBN 9781891519055.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 783–784.

- "Bellomont, Richard Coote, Earl of". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2001. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- "History". trinitywallstreet.org. 26 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Question of the Day: Trinity's Very Own Pirate?". The Archivist's Mailbag. Trinity Church. 19 November 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Sterling, Bruce (2 February 2018). "Mrs. Captain Kidd, shore-side piratess". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Zacks, pp. 82–83, 86.

- Hamilton, (1961) p.?

- "A secret agreement between pirate hunters, 1696". Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- Frank R. Stockton. "Buccaneers and Pirates of Our Coasts" "The Real Captain Kidd". The Baldwin Online Children's Literature Project. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Botting (1978) p.106

- Cordingly (1995), p.183

- Harris, Graham (2002). Treasure and Intrigue The Legacy of Captain Kidd. Dundurn. pp. 114–115. ISBN 9781550024098. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Pirates of the High Seas – Capt. William Kidd". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ""Quedagh Merchant" (ship)". Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Hamilton, (1961)

- Office, Great Britain Public Record (1908). Calendar of State Papers: Colonial Series ... London: Longman. pp. 486–487. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Charles Johnson (1728). The History of the Pyrates, p. 75.

- Zacks, p. 185-86.

- Jameson, John Franklin (1923). Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period by J. Franklin Jameson. New York: Macmillan. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Westergaard, Waldemar (1917). The Danish West Indies Under Company Rule (1671–1754): With a Supplementary Chapter, 1755–1917. New York: Macmillan. pp. 115–118. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "Long Island Genealogy". longislandgenealogy.com. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Richard Zacks, The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd (Hyperion, 2003)

- "The Quest for the Armenian Vessel, Quedagh Merchant" (PDF). AYAS Nautical Research Club. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- "Legend of Capt. Kidd". Newsday. 12 April 2009. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Zacks, p. 364.

- Armstrong, Catherine; Chmielewski, Laura M. (4 December 2013). The Atlantic Experience: Peoples, Places, Ideas. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-40434-3.

- Ralph Delahaye Paine (1911). The Book of Buried Treasure: Being a True History of the Gold, Jewels, and Plate of Pirates, Galleons, Etc., which are Sought for to this Day. Heinemann. p. 124.

- The complete words of the original broadside song "Captain Kid's Farewel to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate's Lament, to the tune of Coming Down" are at davidkidd.net. "Captain Kidd Lyrics. The lyrics of Captain Kidd from 1701 to today". 23 July 2011. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- The genealogy of the historic tune can also be found at davidkidd.net.

- Kanaga, Matt (27 April 2011). "Cockenoe Island: Farm? Distillery? Power plant? Buried Treasure?". Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Zacks, Richard (2002). The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. Hyperion. pp. 241–243. ISBN 0786884517. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- Ralph Delahaye Paine (1911). The Book of Buried Treasure: Being a True History of the Gold, Jewels, and Plate of Pirates, Galleons, Etc., which are Sought for to this Day. Heinemann. p. 304.

- Caulkins, Frances Manwaring (1852). History of New London, Connecticut. p. 293.

- "Grand Manan – Captain Kidd's Money Cove". pennystockjournal.blogspot.co.uk. Penny Stock Journal. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Branigin, William (12 May 1984). "Tracking Captain Kidd's Treasure Puts Pair in Vietnamese Captivity". The Washington Post.

- "Captain Kidd (1645–1701)". PortCities London. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- "Captain Kidd Ship Found". Yahoo News. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- "Captain Kidd's Shipwreck Of 1699 Discovered". Science Daily. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- "IU team finds fabled pirate ship". INDYSTAR.COM. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- Falkenstein, Jaclyn (16 March 2010). "Children's Museum Reveals First Major Component of National Geographic Treasures of the Earth". The Children's Museum of Indianapolis Press Release. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- "Pirate Captain Kidd's 'treasure' found in Madagascar". BBC. 7 May 2015.

- Elgot, Jessica (7 May 2015). "'Captain Kidd's treasure' found off Madagascar". Retrieved 8 January 2017 – via The Guardian.

- Leopold, Todd. "Capt. Kidd's treasure found off Madagascar, report says". cnn.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Captain Kidd's treasure 'found' in Madagascar". telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "PressReader.com – Connecting People Through News". pressreader.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Mission to Madagascar". UNESCO Scientific and Technical Advisory Body assists Madagascar. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- https://www.discogs.com/Ella-Mae-Morse-With-Billy-May-And-His-Orchestra-Captain-Kidd-Ya-Betcha-/release/8542320

- Seitz, Don Carlos (1 March 2002). Under the Black Flag: Exploits of the Most Notorious Pirates. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486421315.

- Marley, David (2010). Pirates of the Americas. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842012. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

Bibliography

- Botting, Douglas (1978). The Pirates. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Company. ISBN 0316848948. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Cordingly, David (1995). Under The Black Flag : The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. Harcourt Brace & Company.

- Hamilton, Cochran (1961). Pirates of the Spanish Main. American Heritage Junior Library (1st ed.). New York: American Heritage. ISBN 0060213469. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

Further reading

Books

- Campbell (1853). An Historical Sketch of Robin Hood and Captain Kid. New York.

- Dalton, Sir Cornelius Neale (1911). The Real Captain Kidd: A Vindication. New York: Duffield.

- Gilbert, H. (1986). The Book of Pirates. London: Bracken Books.

- Howell, T. B., ed. (1701). "The Trial of Captain William Kidd and Others, for Piracy and Robbery". A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanors. XIV. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown (published 1816). pp. 147–234. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Ritchie, Robert C. (1986). Captain Kidd and the War against the Pirates. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Wilkins, Harold T. (1937). Captain Kidd and His Skeleton Island. New York: Liveright Publishing Corp.

- Zacks, Richard (2002). The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. Hyperion Books. ISBN 0-7868-8451-7.

- Konstam, Angus (2008). The Complete History of Piracy. (Osprey Publishing).

Articles

- Captain Kidd Pirate's Treasure Buried in the Connecticut River

- The King's Commission to William Kidd for the Capture of Captain Thomas Tew and Others

- Biography at piratesinfo.com

- Dave's Blog Blog, observer with the Indiana University expedition to the Quedagh Merchant (ongoing)

- National Archives – Article listing Records held concerning Captain Kidd

- Pirates and the history of Lordship, Connecticut

- Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Captain William Kidd The court documents of the trial of William Kidd, in Early Modern English.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1892 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about William Kidd. |

- Captain Kidd pub, What's in Wapping? Local community website