Bohor reedbuck

The bohor reedbuck (Redunca redunca) is an antelope native to central Africa. The animal is placed under the genus Redunca and in the family Bovidae. It was first described by German zoologist and botanist Peter Simon Pallas in 1767. The bohor reedbuck has five subspecies. The head-and-body length of this medium-sized antelope is typically between 100–135 cm (39–53 in). Males reach approximately 75–89 cm (30–35 in) at the shoulder, while females reach 69–76 cm (27–30 in). Males typically weigh 43–65 kg (95–143 lb) and females 35–45 kg (77–99 lb). This sturdily built antelope has a yellow to grayish brown coat. Only the males possess horns which measure about 25–35 cm (9.8–13.8 in) long.

| Bohor reedbuck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male bohor reedbuck in Serengeti, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Genus: | Redunca |

| Species: | R. redunca |

| Binomial name | |

| Redunca redunca (Pallas, 1767) | |

| Subspecies[2] | |

|

Subspecies list

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

A herbivore, the bohor reedbuck prefers grasses and tender reed shoots with high protein and low fiber content. This reedbuck is dependent on water, though green pastures can fulfill its water requirement. The social structure of the bohor reedbuck is highly flexible. Large aggregations are observed during the dry season, when hundreds of bohor reedbuck assemble near a river. Males become sexually mature at the age of three to four years, while females can conceive at just one year of age, reproducing every nine to fourteen months. Though there is no fixed breeding season, mating peaks in the rainy season. The gestation period is seven and a half months long, after which a single calf is born. The calves are weaned at eight to nine months of age.

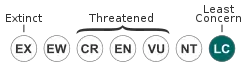

The bohor reedbuck inhabits moist grasslands and swamplands as well as woodlands. The bohor reedbuck is native to Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania and Togo. The animal is possibly extinct in Ivory Coast and Uganda. Reckless hunting and loss of habitat as a result of human settlement have led to significant decline in the numbers of the bohor reedbuck, although this antelope tends to survive longer in such over-exploited areas as compared to its relatives. The total populations of the bohor reedbuck are estimated to be above 100,000. Larger populations occur in eastern and central Africa than in western Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) rates the bohor reedbuck as of least concern.

Taxonomy

The scientific name of the bohor reedbuck is Redunca redunca. The animal is placed under the genus Redunca and in the family Bovidae. It was first described by German zoologist and botanist Peter Simon Pallas in 1767.[2] The three species of Redunca, including the bohor reedbuck, are the least derived members of the tribe Reduncini (except the genus Pelea). The order of size in the genus Redunca is an evidence supporting the descent of the reduncines from a small ancestor.[3]

Five subspecies of the bohor reedbuck have been recognized:[3][4]

- R. r. bohor Rüppell, 1842: Also known as the Abyssinian bohor reedbuck. It occurs in southwestern, western and central Ethiopia, and Blue Nile (Sudan).

- R. r. cottoni (W. Rothschild, 1902): It occurs in the Sudds (Southern Sudan), northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and probably in northern Uganda. R. r. donaldsoni is a synonym.

- R. r. nigeriensis (Blaine, 1913): This subspecies occurs in Nigeria, northern Cameroon, southern Chad and Central African Republic.

- R. r. redunca (Pallas, 1767): Its range extends from Senegal east to Togo. It inhabits the northern savannas of Africa. The relationship of this subspecies to R. r. nigeriensis is not clear.

- R. r. wardi (Thomas, 1900): Found in Uganda, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and eastern Africa. R. r. ugandae and R. r. tohi are synonyms.

Physical description

_male.jpg.webp)

The bohor reedbuck is a medium-sized antelope. The head-and-body length is typically between 100–135 cm (39–53 in).[5] Males reach approximately 75–89 cm (30–35 in) at the shoulder, while females reach 69–76 cm (27–30 in).[6] Males typically weigh 43–65 kg (95–143 lb) and females 35–45 kg (77–99 lb). The bushy tail is 18–20 cm (7.1–7.9 in) long.[5][7] This reedbuck is sexually dimorphic, with males 10% to 20% larger than females and showing more prominent markings.[6][8] Of the subspecies, R. r. cottoni is the largest, whereas R. r. redunca is the smallest.[3]

This sturdily built antelope has a yellow to grayish-brown coat. Generally, the bohor reedbuck is yellower than other reedbucks. The large and diffuse sebaceous glands present on the coat make the coat greasy and give it a strong odor.[9] Juveniles are darker than the adults as well as long-haired.[6] While R. r. bohor appears yellowish gray, R. r. wardi is richly tinted.[3] The undersides are white in color. A few distinct markings can be observed—such as a dark stripe on the front of each foreleg; white markings under the tail; and a pale ring of hair around the eyes and along the lips, lower jaw, and upper throat.[5][6] However, R. r. redunca lacks dark stripes on its forelegs.[3] The males have thicker necks. Its large, oval-shaped ears distinguish it from other antelopes.[10] There is a round bare spot below each ear.[6] Apart from sebaceous glands, bohor reedbuck have a pair of inguinal glands and vestigial foot glands, and four nipples.[9] A bohor reedbuck can survive for at least ten years.[8] The tracks of the bohor reedbuck are slightly smaller than those of the southern reedbuck.[11]

As a prominent sign of sexual dimorphism, only males possess a pair of short, stout horns, that extend backward from the forehead and hook slightly forward.[8] The horns measure about 25–35 cm (9.8–13.8 in).[5] However, some Senegalese individuals have longer and wide-spreading horns.[8] In comparison to the other reedbucks, the bohor reedbuck has the shortest and most hooked horns.[12] The longest horns are observed in R. r. cottoni, which are hooked less than normal and may curve inwards. In contrast to R. r. cottoni, R. r. bohor has short and stout horns, with hooks pointing forward.[3] The length of the horns of an individual of a certain region seems to be related to the population density in that region to some extent. While short horns are observed in individuals of eastern Africa, where populations are dispersed, longer and wide-spreading horns are found on animals in the Nile valley, where populations are concentrated.[4]

Ticks and parasites

The bohor reedbuck is host to several parasites. The most notable helminths found in the bohor reedbuck are Carmyerius papillatus (in the rumen), Stilesia globipunctata (in the small intestine), Trichuris globulosa (in the caecum), Setaria species (in the abdominal cavity), Dictyocaulus species (in the lungs) and Taenia cysts (in the muscles). Other parasites include Schistosoma bovis, Cooperia rotundispiculum, Haemonchus contortus, species of Oesophagostomum, Amphistoma and Stilesia. The common ticks found on the bohor reedbuck are Amblyomma species and Rhipicephalus evertsi.[3]

Ecology and behavior

Bohor reedbuck are active throughout the day, seeking cover during the daytime and grazing in the night. A large proportion of the whole day is spent on feeding and vigilance.[13] They can easily camouflage in grasses and reeds, and hide themselves rather than running from danger.[8] When threatened, they usually remain motionless or retreat slowly into cover for defense, but if the threat is close, they flee, whistling shrilly to alert the others. It hides from predators rather than forming herds in defense. Many predators, including lions, leopards, spotted hyenas, African wild dogs and Nile crocodiles, prey on the reedbuck.[5]

If shade is available, females remain solitary; otherwise, they, along with their offspring, congregate to form herds of ten animals. Female home ranges span over 15–40 hectares (37–99 acres; 0.058–0.154 sq mi), while the larger territories of males cover 25–60 hectares (62–148 acres; 0.097–0.232 sq mi). These home ranges keep overlapping. As the daughters grow up, they distance themselves from their mothers' home ranges. Territorial males are much tolerant; they may even associate with up to 19 bachelor males in the absence of females. As many as five females may be found in a male's territory. Territorial bulls drive out their sons when they start developing horns (when they are about a year-and-a-half old). These young males form groups of two to three individuals on the borders of territories, till they themselves mature in their fourth year.[8] Large aggregations are observed during the dry season, when hundreds of bohor reedbuck assemble near a river.[6]

Two prominent forms of display among these animals is whistling and bounding. Instead of scent-marking its territory, the reedbuck will give a shrill whistle to make the boundaries of its territory be known. As it whistles, it expels air through its nose with such a force that the whole of its body vibrates. These whistles, usually one to three in number, are followed by a few stotting bounds. This behavior is also used to raise alarm in herds. In this, the reedbuck raises its neck, exposing the white patch on its throat, but keeping the tail down, and leaps in a way similar to the impala's jumps, landing on its forelegs. This is accompanied by the popping of the inguinal glands in the legs. Fights begin with both opponents holding their horns low, in a combat stance; followed by the locking of horns and pushing one another. These fights can even lead to deaths.[9]

Diet

A herbivore, the bohor reedbuck prefers grasses and tender reed shoots with high protein and low fiber content. This reedbuck is dependent on water, though green pastures can fulfill its water requirement.[6] A study of the bohor reedbuck's diet in Rwenzori Mountains National Park (Uganda) revealed that, throughout the year, the most preferred species was Sporobolus consimilis. Other grasses the animals fed on included Hyparrhenia filipendula, Heteropogon contortus and Themeda triandra, all of which are species commonly found in heavily grazed grasslands. Bohor reedbuck preferred Cynodon dactylon and Cenchrus ciliaris in the wet season, and switched to Sporobolus pyramidalis and Panicum repens in the dry season. Though they rarely feed on dicots, these can include Capparis and Sida species. On regularly burnt pastures, the bohor reedbuck feeds on Imperata species, while in places close by water sources, it eats Leersia and newly sprouted Vossia species (like topi and puku).[3]

Primarily a nocturnal grazer, the bohor reedbuck may also feed at daytime. A study showed that feeding peaked at dawn and late afternoon. In the night, two feeding peaks were observed once again: at dusk and midnight.[14] They traverse a long way from their daytime refuges while grazing. Seasonal differences in the amount of time spent while grazing in a particular area is possibly related to the availability and quality of grasses there.[3] The bohor reedbuck often grazes in association with other grazers such as hartebeest, topi, puku and kob. In Kenyan farmlands, the reedbuck may feed on growing wheat and cereals.[8]

Reproduction

Males become sexually mature at the age of three to four years, while females can conceive at just one year of age, reproducing every nine to fourteen months. Though there is no fixed breeding season, mating peaks in the rainy season.[9] Fights for dominance take place in some particular "assembly fields", where up to 40 males may assemble in an area of 1 hectare (2.5 acres; 0.0039 sq mi). Some parts of these grounds are the main attractions - marked with dung and urine. The reason behind the attractiveness of these few spots for sexually active males is the oestrogen in the females' urine.[4]

Courtship begins with the dominant male approaching the female, who then assumes a low-head posture and urinates. Unresponsive females run away on being pursued by a male. A male keen on sniffing the female's vulva keeps flicking his tongue. As they continue their "mating march", the male licks the female's rump and persistently attempts mounting her. On mounting, the males tries to clasp her flanks tightly. If she stands firmly, it is a sign that she is ready to mate. Copulation is marked by a single ejaculation, after which both animals stand motionless or a while, and then resume grazing.[6][9]

The gestation period is seven and a half months long, after which a single calf is born. The mothers keep their offspring concealed for as long as eight weeks. The mother keeps within a distance of 20–30 m (66–98 ft) of its calf. Nursing, usually two to four minutes long, involves licking the whole body of the calf and suckling. The infant is suckled usually once in the day and one to two times at night. The female's previous calf usually resists separation. At the age of two months, the calf begins grazing alongside its mother, and seeks protection from her if alarmed. Though after four months the calf is no more licked, it may still be groomed by its mother.[9] The calves are weaned at eight to nine months of age.[6]

Habitat and distribution

The bohor reedbuck inhabits moist grasslands and swamplands as well as woodlands. It is found in two kinds of habitat in northern Cameroon: the seasonally flooded grasslands rich in grasses like Vetiveria nigritana and Echinochloa pyramidalis (in the Sahelo-Sudan region) and Isoberlina woodlands (in the Sudano-Guinean region).[3] Often found on grasslands susceptible to floods and droughts, the bohor reedbuck can adapt remarkably well to radical seasonal changes and calamities.[15] It is not so widespread as the bushbuck due to its habitat requirements.[16] In some margins of its range, the bohor reedbuck shares its habitat with the mountain reedbuck. The ranges of the bohor reedbuck and southern reedbuck extensively overlap in Tanzania.[3]

Endemic to Africa, the bohor reedbuck is native to Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania and Togo. The animal is possibly extinct in Ivory Coast and Uganda.[1] Formerly widespread in western, central and eastern Africa, its present range extends from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east.[17] Among the three reedbuck species, bohor reedbuck is the most widespread in Tanzania.[18] Its status in Burundi, Eritrea, Ghana and Togo is uncertain, while it is rare in Niger and Nigeria.[3]

Threats and conservation

Reckless hunting and loss of habitat as a result of human settlement have led to a significant decline in the numbers of the bohor reedbuck,[19] although this antelope tends to survive longer in such over-exploited areas as compared to its relatives.[17] Natural calamities, like drought, are also major threats. While populations have declined in northern Cameroon due to degradation of floodplains through the construction of upstream dams,[1] their habitat has been destroyed in Chad and Tanzania due to expansion of agriculture and settlement.[3] Several deaths occur due to roadkill and drowning as well.[3] During the dry season, bohor reedbuck are hunted with dogs and nets in Uganda. Reedbuck with the largest horns are prized by hunters.[6]

The total populations of the bohor reedbuck are estimated to be above 100,000. Though the populations are decreasing, it is not sufficiently low to meet the near threatened criterion. Thus, the IUCN rates the bohor reedbuck as of least concern. Around three-fourths of the populations survive in protected areas.[1] Populations of the reedbuck are either declining or uncertain in Boucle du Baoulé National Park (Mali); Comoé National Park (Ivory Coast); Mole and Digya national parks (Ghana). Numbers in the Akagera National Park, where its last-known populations in Rwanda exist, have seen a steep fall.[3]

Though populations have substantially decreased in western Africa, bohor reedbuck still exist in Niokolo-Koba National Park (Senegal); Corubal River (Guinea-Bissau); Kiang West National Park (Gambia);[20] Arly-Singou and Nazinga Game Ranch (Burkina Faso). Larger numbers occur in eastern and central Africa, mostly in protected areas such as Bouba Ndjida (Cameroon); Manovo-Gounda St. Floris National Park (Central African Republic); Bale Mountains National Park (Ethiopia); Murchison Falls National Park and Pian Upe Wildlife Reserve (Uganda); Maasai Mara (Kenya); Serengeti National Park, Moyowosi-Kigosi and Selous Game Reserve (Tanzania).[17]

References

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008). "Redunca redunca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 722. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Kingdon, J.; Hoffman, M. (2013). Mammals of Africa. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 421, 431–6. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2.

- Kingdon, J. (2013). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. London: Bloomsbury Pub. ISBN 978-1-4081-7481-4.

- Huffman, B. "Bohor reedbuck". Ultimate Ungulate. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Newell, T. L. "Redunca redunca". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Animal Diversity Web.

- Estes, R. D. (1993). The Safari Companion : A Guide to Watching African Mammals, Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, and Primates. Harare (Zimbabwe): Tutorial Press. pp. 75–8. ISBN 0-7974-1159-3.

- Kingdon, J. (1988). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part C. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 351–9. ISBN 0-226-43718-3.

- Estes, R. D. (2004). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals : Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (4th ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 91–3, 94–8. ISBN 0-520-08085-8.

- Kennedy, A. S.; Kennedy, V. (2012). Animals of the Masai Mara. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4491-3.

- Stuart, C.; Stuart, T. (2000). A Field Guide to the Tracks and Signs of Southern and East African Wildlife (3rd ed.). Cape Town: Struik. p. 86. ISBN 1-86872-558-8.

- Rafferty, J. P. (2011). Grazers (1st ed.). New York: Britannica Educational Pub. pp. 116–8. ISBN 978-1-61530-336-6.

- Djagoun, C. A. M. S.; Djossa, B. A.; Mensah, G. A.; Sinsin, B. A. (2013). "Vigilance efficiency and behaviour of bohor reedbuck (Pallas 1767) in a savanna environment of Pendjari Biosphere Reserve (northern Benin)". Mammal Study. 38 (2): 81–9. doi:10.3106/041.038.0203. S2CID 85879802.

- Afework, B.; Bekele, A.; Balakrishnan, M. (7 October 2009). "Population status, structure and activity patterns of the bohor reedbuck Redunca redunca in the north of the Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia". African Journal of Ecology. 48 (2): 502–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2009.01139.x.

- "Bohor reedbuck". Wildscreen. ARKive. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- East, R. (1990). Antelopes : Global Survey and Regional Action Plans. Gland: IUCN. p. 37. ISBN 2-8317-0016-7.

- East, R. (1999). African Antelope Database 1998. Gland, Switzerland: The IUCN Species Survival Commission. pp. 153–7. ISBN 2-8317-0477-4.

- Skinner, A. (2005). Tanzania & Zanzibar (2nd ed.). London: Cadogan Guides. p. 34. ISBN 1-86011-216-1.

- Edroma, E. L.; Kenyi, J. M. (March 1985). "Drastic decline in bohor reedbuck (Redunca redunca Pallas 1977) in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda". African Journal of Ecology. 23 (1): 53–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1985.tb00712.x.

- Stuart, S. N.; Jenkins, M. D.; Adams, R. J. (1990). Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands : Conservation, Management, and Sustainable Use. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. p. 96. ISBN 2-8317-0021-3.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Redunca redunca. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Redunca redunca. |

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Animal, Smithsonian Institution, 2005, pg. 251