Biodiversity hotspot

A biodiversity hotspot is a biogeographic region with significant levels of biodiversity that is threatened by human habitation.[1][2]

Norman Myers wrote about the concept in two articles in “The Environmentalist” (1988),[3] and 1990[4] revised after thorough analysis by Myers and others “Hotspots: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions”[5] and a paper published in the journal Nature.[6]

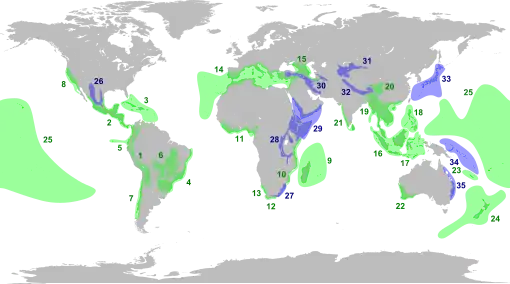

To qualify as a biodiversity hotspot on Myers 2000 edition of the hotspot-map, a region must meet two strict criteria: it must contain at least 0.5% or 1,500 species of vascular plants as endemics, and it has to have lost at least 75% of its primary vegetation.[6] Around the world, 36 areas qualify under this definition.[7] These sites support nearly 60% of the world's plant, bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species, with a very high share of those species as endemics. Some of these hotspots support up to 15,000 endemic plant species and some have lost up to 95% of their natural habitat.[7]

Biodiversity hotspots host their diverse ecosystems on just 2.4% of the planet's surface,[2] however, the area defined as hotspots covers a much larger proportion of the land. The original 25 hotspots covered 11.8% of the land surface area of the Earth.[1] Overall, the current hotspots cover more than 15.7% of the land surface area, but have lost around 85% of their habitat.[8] This loss of habitat explains why approximately 60% of the world's terrestrial life lives on only 2.4% of the land surface area.

Hotspot conservation initiatives

Only a small percentage of the total land area within biodiversity hotspots is now protected. Several international organizations are working in many ways to conserve biodiversity hotspots.

- Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a global program that provides funding and technical assistance to nongovernmental organizations and participation to protect the Earth's richest regions of plant and animal diversity including: biodiversity hotspots, high-biodiversity wilderness areas and important marine regions.

- The World Wide Fund for Nature has derived a system called the "Global 200 Ecoregions", the aim of which is to select priority Ecoregions for conservation within each of 14 terrestrial, 3 freshwater, and 4 marine habitat types. They are chosen for their species richness, endemism, taxonomic uniqueness, unusual ecological or evolutionary phenomena, and global rarity. All biodiversity hotspots contain at least one Global 200 Ecoregion.

- Birdlife International has identified 218 “Endemic Bird Areas” (EBAs) each of which hold two or more bird species found nowhere else. Birdlife International has identified more than 11,000 Important Bird Areas[9] all over the world.

- Plant life International coordinates several the world aiming to identify Important Plant Areas.

- Alliance for Zero Extinction is an initiative of many scientific organizations and conservation groups who co-operate to focus on the most threatened endemic species of the world. They have identified 595 sites, including many Birdlife’s Important Bird Areas.

- The National Geographic Society has prepared a world map[10] of the hotspots and ArcView shapefile and metadata for the Biodiversity Hotspots[11] including details of the individual endangered fauna in each hotspot, which is available from Conservation International.[12]

By the influence of that the central government of India arrived a new authority named CAMPA (Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority) to control the destruction of forests and biological spots in India.

Distribution by region

North and Central America

- California Floristic Province •8•

- Madrean pine-oak woodlands •26•

- Mesoamerica •2•

- North American Coastal Plain •36•[13][14]

The Caribbean

- Caribbean Islands •3•

- Atlantic Forest •4•

- Cerrado •6•

- Chilean Winter Rainfall-Valdivian Forests •7•

- Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena •5•

- Tropical Andes •1•

- Mediterranean Basin •14•

- Cape Floristic Region •12•

- Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa •10•

- Eastern Afromontane •28•

- Guinean Forests of West Africa •11•

- Horn of Africa •29•

- Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands •9•

- Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany •27•

- Succulent Karoo •13•

- Eastern Himalaya •32•

- Indo-Burma, India and Myanmar •19•

- Western Ghats and Sri Lanka •21•

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

- East Melanesian Islands •34•

- New Caledonia •23•

- New Zealand •24•

- Philippines •18•

- Polynesia-Micronesia •25•

- Eastern Australian temperate forests •35•

- Southwest Australia •22•

- Sundaland and Nicobar islands of India •16•

- Wallacea •17•

- Japan •33•

- Mountains of Southwest China •20•

- Caucasus •15•

- Irano-Anatolian •30•

Critiques of "Hotspots"

The high profile of the biodiversity hotspots approach has resulted in some criticism. Papers such as Kareiva & Marvier (2003)[15] have argued that the biodiversity hotspots:

- Do not adequately represent other forms of species richness (e.g. total species richness or threatened species richness).

- Do not adequately represent taxa other than vascular plants (e.g. vertebrates, or fungi).

- Do not protect smaller scale richness hotspots.

- Do not make allowances for changing land use patterns. Hotspots represent regions that have experienced considerable habitat loss, but this does not mean they are experiencing ongoing habitat loss. On the other hand, regions that are relatively intact (e.g. the Amazon basin) have experienced relatively little land loss, but are currently losing habitat at tremendous rates.

- Do not protect ecosystem services.

- Do not consider phylogenetic diversity.[16]

A recent series of papers has pointed out that biodiversity hotspots (and many other priority region sets) do not address the concept of cost.[17] The purpose of biodiversity hotspots is not simply to identify regions that are of high biodiversity value, but to prioritize conservation spending. The regions identified include some in the developed world (e.g. the California Floristic Province), alongside others in the developing world (e.g. Madagascar). The cost of land is likely to vary between these regions by an order of magnitude or more, but the biodiversity hotspot designations do not consider the conservation importance of this difference. However, the available resources for conservation also tend to vary in this way.

See also

- Biodiversity – Variety and variability of life forms

- Conservation biology – The study of threats to biological diversity

- Crisis ecoregion

- Ecoregion – Ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion

- Global 200

- Hawaiian honeycreeper conservation

- High-Biodiversity Wilderness Area

- Hope spot: biodiversity hotspots in the open sea

- Key Biodiversity Area

- Megadiverse countries – Nation with extremely high biological diversity or many endemic species

- Protected area

- Wilderness – Undisturbed natural environment

References

- "Biodiversity Hotspots in India". www.bsienvis.nic.in.

- "Why Hotspots Matter". Conservation International.

- Myers, N. (1988). "Threatened biotas: "Hot spots" in tropical forests". Environmentalist. 8: 187–208. doi:10.1007/BF02240252.

- Myers, N. The Environmentalist 10 243-256 (1990)

- Russell A. Mittermeier, Norman Myers and Cristina Goettsch Mittermeier, Hotspots: Earth's Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions, Conservation International, 2000 ISBN 978-968-6397-58-1

- Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities" (PDF). Nature. 403 (6772): 853–858. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..853M. doi:10.1038/35002501. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 10706275. S2CID 4414279.

- "Biodiversity hotspots defined". Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Conservation International. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Biodiversity Hotspots". www.e-education.psu.edu.

- Archived August 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Conservation International" (PDF). The Biodiversity Hotspots. 2010-10-07. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- "Conservation International". The Biodiversity Hotspots. 2010-10-07. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- "Resources". Biodiversityhotspots.org. 2010-10-07. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- "North American Coastal Plain". Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Noss, Reed F.; Platt, William J.; Sorrie, Bruce A.; Weakley, Alan S.; Means, D. Bruce; Costanza, Jennifer; Peet, Robert K. (2015). "How global biodiversity hotspots may go unrecognized: lessons from the North American Coastal Plain" (PDF). Diversity and Distributions. 21 (2): 236–244. doi:10.1111/ddi.12278.

- Kareiva, P. and M. Marvier (2003) Conserving Biodiversity Coldspots, American Scientist, 91, 344-351.

- Daru, Barnabas H.; van der Bank, Michelle; Davies, T. Jonathan (2014). "Spatial incongruence among hotspots and complementary areas of tree diversity in southern Africa". Diversity and Distributions. 21 (7): 769–780. doi:10.1111/ddi.12290.

- Possingham, H. and K. Wilson (2005) Turning up the heat on hotspots, Nature, 436, 919-920.

Further reading

- Dedicated issue of Philosophical Transactions B on Biodiversity Hotspots. Some articles are freely available.

- Spyros Sfenthourakis, Anastasios Legakis: Hotspots of endemic terrestrial invertebrates in Southern Greece. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001

External links

- A-Z of Areas of Biodiversity Importance: Biodiversity Hotspots

- Conservation International's Biodiversity Hotspots project

- African Wild Dog Conservancy's Biodiversity Hotspots Project

- Biodiversity hotspots in India

- New biodiversity maps color-coded to show hotspots

- Shapefile of the Biodiversity Hotspots (v2016.1)