Battle of Polygon Wood

The Battle of Polygon Wood took place from 26 September to 3 October 1917, during the second phase of the Third Battle of Ypres in the First World War. The battle was fought near Ypres in Belgium, in the area from the Menin road to Polygon Wood and thence north, to the area beyond St Julien.[lower-alpha 1] Much of the woodland had been destroyed by the huge quantity of shellfire from both sides since 16 July and the area had changed hands several times.

| Battle of Polygon Wood | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Passchendaele on the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Australian infantry wearing respirators | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

7 British divisions 2 Australian divisions | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

British: 15,375 Australian: 5,770 | 13,500: 21–30 September | ||||||

General Herbert Plumer continued the series of British general attacks with limited objectives. The attacks were led by lines of skirmishers, followed by small infantry columns organised in depth (a formation which had been adopted by the Fifth Army in August) with a vastly increased amount of artillery support, the infantry advancing behind five layers of creeping barrage on the Second Army front.

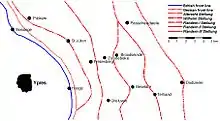

The advance was planned to cover 1,000–1,500 yd (910–1,370 m) and stop on reverse slopes, which were easier to defend, enclosing ground which gave observation of German reinforcement routes and counter-attack assembly areas. Preparations were then made swiftly to defeat German counter-attacks, by mopping-up and consolidating the captured ground with defences in depth. The attack inflicted a severe blow on the German 4th Army, causing many losses, capturing a significant portion of Flandern I Stellung, the fourth German defensive position, which threatened the German hold on Broodseinde ridge.

The drier weather continued to benefit the British attackers by solidifying the ground and raising mist which obscured British infantry attacks made around dawn. The mist cleared during the morning and revealed German Eingreif (counter-attack) formations to air and ground observation, well in advance of their arrival on the battlefield.[2] German methodical counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe) from 27 September – 3 October failed and German defensive arrangements were changed hastily after the battle to try to counter British offensive superiority.[3]

Background

Tactical developments

The preliminary operation to capture Messines ridge (7–14 June) had been followed by a strategic pause as the British repaired their communications behind Messines ridge, completed the building of the infrastructure necessary for a much larger force in the Ypres area and moved troops and equipment north from the Arras front.[4] After delays caused by local conditions, the Battles of Ypres had begun on 31 July with the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, which was a substantial local success for the British, taking a large amount of ground and inflicting many casualties on the German defenders.[5] The Germans had recovered some of the lost ground in the middle of the attack front and restricted the British advance on the Gheluvelt Plateau further south. British attacks had then been seriously hampered by unseasonal heavy rain during August and had not been able to retain much of the additional ground captured on the plateau on 10, 16–18, 22–24 and 27 August due to the determined German defence, mud and poor visibility.[6]

Haig ordered artillery to be transferred from the southern flank of the Second Army and more artillery to be brought into Flanders from the armies further south, to increase the weight of the attack on the Gheluvelt Plateau.[lower-alpha 2] The principal role was changed from the Fifth to the Second Army and the boundary between the two armies was moved north towards the Ypres–Roulers railway, to narrow the frontages of the Second Army divisions on the Gheluvelt Plateau. A pause in British attacks was used to reorganise and to improve supply routes behind the front line, to carry forward 54,572 long tons (55,448 t) of ammunition above normal expenditure. Guns were moved forward to new positions and the infantry and artillery reinforcements practised for the next attack. The unseasonal rains stopped, the ground began to dry and the cessation of British attacks misled the Germans, who risked moving some units away from Flanders.[8] The offensive had resumed on 20 September with the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, using similar step-by-step methods to those of the Fifth Army after 31 July, with a further evolution of technique, based on the greater mass of artillery made available to enable the consolidation of captured ground with sufficient strength and organisation to defeat German counter-attacks.[9] Most of the British objectives had been captured and held, with substantial losses being inflicted on the six German ground-holding divisions and their three supporting Eingreif divisions.[10] British preparations for the next step began immediately and both sides studied the effect of the battle and the implications it had for their dispositions.[11][12]

Prelude

British preparations

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.0 | 66 | dull |

| 21 | 0.0 | 62 | dull |

| 22 | 0.0 | 63 | fine |

| 23 | 0.0 | 65 | fine |

| 24 | 0.0 | 74 | dull |

| 25 | 0.0 | 75 | mist |

| 26 | 0.5 | 68 | mist |

| 27 | 0.0 | 67 | dull |

On 21 September, Haig instructed the Fifth Army (General Hubert Gough) and Second Army (General Herbert Plumer) to make the next step across the Gheluvelt Plateau, on a front of 8,500 yd (4.8 mi; 7.8 km). The I Anzac Corps (Lieutenant-BGeneral William Birdwood) would conduct the main advance of about 1,200 yd (1,100 m), to complete the occupation of Polygon Wood and the south end of Zonnebeke village.[14] The Second Army altered its corps frontages soon after the attack of 20 September so that each attacking division could be concentrated on a 1,000 yd (910 m) front. Roads and light railways were built behind the new front line to move artillery and ammunition forward, beginning on 20 September; in fine weather this was finished in four days. As before Menin road, bombardment and counter-battery fire began immediately, with practice barrages fired daily as a minimum. Artillery from the VIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston) and IX Corps (Lieutenant General Alexander Hamilton-Gordon) in the south conducted bombardments to simulate attack preparations on Zandvoorde and Warneton. Haig intended that later operations would capture the rest of the ridge from Broodseinde, giving the Fifth Army scope to advance beyond the ridge north-eastwards and allow the commencement of Operation Hush.[14]

The huge amounts of shellfire from both sides had cut up the ground and destroyed roads. New road circuits were built to carry supplies forward, especially artillery ammunition. Heavier equipment bogged in churned mud so had to be brought forward by wagons along roads and tracks, many of which were under German artillery observation from Passchendaele ridge, rather than being moved cross-country. The I Anzac Corps had 205 heavy guns, one for every 9 m (9.8 yd) of front and many field artillery brigades with 18-pounder guns and 4.5-inch howitzers, which with the guns of the other attacking corps, were moved forward 2,000 yd (1,800 m) from 20–24 September. Assembled forward of the artillery were heavy Vickers machine-guns of the divisional machine-gun companies, 56 for the creeping machine-gun barrage and 64 SOS guns for emergency barrages against German counter-attacks and to increase the barrage towards the final objective.[15]

The frontages of VIII and IX Corps were moved northwards so that X Corps (Lieutenant-General Thomas Morland) could take over 600 yd (550 m) of front up to the southern edge of Polygon Wood, which kept the frontages of the two Australian divisions of I Anzac Corps to 1,000 yd (910 m). The 39th Division took over from the 41st Division, ready to attack Tower Hamlets (at the top of the Bassevillebeek spur), the 33rd Division replaced the 23rd Division beyond the Menin road and the 5th and 4th Australian divisions replaced the 1st and 2nd Australian divisions in Polygon Wood.[16] The Action of 25 September 1917 took place between the Menin road and Polygon Wood as the 33rd Division was taking over from the 23rd Division; for a time the German attack threatened to delay preparations for the British attack due the next day. Some ground was captured by the Germans and part of it was then recaptured by the 33rd Division. Plumer ordered that the flank guard protecting the I Anzac Corps on 26 September be formed by the 98th Brigade of the 33rd Division while the 100th Brigade recaptured the lost ground.[17]

Plan

Dispersed and camouflaged German defences, using shell-hole positions, pillboxes, with much of the German infantry held back for counter-attacks, meant that as British units advanced and became weaker and disorganised by losses, fatigue, poor visibility and the channelling effect of waterlogged ground, they met more and fresher German defenders.[18] The German defensive system had been more effective in the unusually rainy weather in August, making movement much more difficult and forcing the British to keep to duckboard tracks, easy to identify and bombard. Objectives were chosen to provide the British infantry with good positions from which to face German counter-attacks, rather than to advance with unlimited objectives. The Fifth Army had set objectives much closer than 3,000–3,500 yd (1.7–2.0 mi; 2.7–3.2 km) after 31 July and the Second Army methods of September were based on SS 144 The Normal Formation for the Attack (February 1917), reflecting the experience of the fighting in August and to exploit opportunities made possible by the reinforcement of the Flanders front with another 626 guns before 20 September.[19][lower-alpha 3]

The methods based on the Second Army Note of 31 August had proved themselves on 20 September and were to be repeated.[23] The extra infantry made available, by increasing the number of divisions and narrowing attack frontages, had greater depth than the August attacks. The leading waves of infantry were lightly equipped, further apart and followed by files or small groups ready to swarm around German defences uncovered by the skirmish lines. Each unit kept a sub-unit in close reserve, brigades a reserve battalion, battalions a reserve company and companies a reserve platoon.[24] The manual SS 144 (February 1917) reiterated the platoon organisation laid down in SS 143 and recommended an attacking frontage of 200 yd (180 m) for a battalion, with wide intervals between each man, line and wave, to create a dispersed attack in depth. Where one or two objectives were to be captured, the first wave should advance to the final objective, with troops in following waves to mop-up and occupy the captured ground. Where more objectives were set, the first wave was to stop at the first objective, mop-up and dig in, ready to receive German counter-attacks, as following waves leapfrogged beyond them to the further objectives and did the same, particularly when enough artillery was present to provide covering fire for all of the depth of the attack.[25]

The leap-frog method was chosen for the September attacks, whereas in July and August both methods had been used.[26] Intermediate objectives closer to the front line were selected and the number of infantry attacking the first objective was reduced, since the German garrisons in the forward defended areas were small and widely dispersed. A greater number of units leapfrogged through to the next objective and the distance to the final objective was further reduced, to match the increasing density of German defences; the creeping barrage slowed as it moved towards the final objective.[27] Particular units were allotted to mop-up and occupy areas behind the most advanced troops, to make certain that pockets of Germans overrun by the foremost troops were killed or captured, before they could emerge from shelter and re-join the battle. Increased emphasis was placed on Lewis-guns, rifle-fire and rifle-grenades. Hand-grenades were given less emphasis in favour of more rifle training. The proportion of smoke ammunition for rifle grenades and Stokes mortars was increased, to blind the occupants of German pillboxes as they were being surrounded. All units were required to plan an active defence against counter-attack, using the repulse of German infantry as an opportunity to follow up and inflict more casualties.[28]

X Corps was to advance to create a defensive flank on the right, attacking with the 33rd and 39th divisions either side of the Menin road. The main attack was to be conducted by the I Anzac Corps with the 5th and 4th Australian divisions on the remainder of Polygon Wood and the southern part of Zonnebeke village. The Australian attack was in two stages, 800–900 yd (730–820 m) to the Butte and Tokio pillbox and after a one-hour pause for consolidation, a final advance beyond the Flandern I Stellung and the Tokio spur. To the north, V Corps of the Fifth Army with the 3rd and 59th (2nd North Midland) divisions was to reach a line from Zonnebeke to Hill 40 and Kansas Farm crossroads, using the smoke and high explosive barrage (rather than shrapnel) demonstrated by the 9th (Scottish) Division on 20 September.[29] A brigade of the 58th (2/1st London) Division, (XVIII Corps) was to attack up Gravenstafel spur towards Aviatik Farm. The relief of V Corps by II Anzac Corps, to bring the ridge as far north as Passchendaele into the Second Army area was postponed because the 1st and 2nd Australian divisions were still battle-worthy.[30]

German preparations

Tower Hamlets spur overlooked the ground south towards Zandvoorde. The upper valleys of the Reutelbeek and Polygonebeek further north offered a commanding view of the German counter-attack assembly areas in the low ground north of the Menin road. The Butte de Polygone a large mound in Polygon Wood was part of the Wilhelmstellung and had been fortified with dugouts and foxholes. The Butte gave observation of the east end of the Gheluvelt Plateau towards Becelaere and Broodseinde.[31] By mid-1917, the area east of Ypres had six German defensive positions, the front position, the Albrechtstellung (second position), Wilhelmstellung (third position), Flandern I Stellung (fourth position), Flandern II Stellung (fifth position) and Flandern III Stellung (under construction). Between the German positions lay the Belgian villages of Zonnebeke and Passchendaele.[32]

The German defences had been arranged in a forward zone, main battle zone and rearward battle zone and after the defeat of 20 September, the 4th Army tried to adapt its defensive methods to the British tactics.[33] At a conference on 22 September, the German commanders decided to increase the artillery effort between battles, half for counter-battery fire and half against British infantry. The accuracy of German artillery fire was to be improved by increasing the amount of artillery observation available to direct fire during British attacks. Infantry raiding was to be stepped up and counter-attacks to be made more quickly.[34] By 26 September, the ground-holding divisions had been reorganised so that their regiments were side by side, covering a front of about 1,000 yd (910 m) each, with the battalions one-behind-the-other, the first in the front line, one in support and the third in reserve, over a depth of 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km).[35] Each of the three ground-holding divisions on the Gheluvelt Plateau had an Eingreif division in support, double the ratio on 20 September.[36]

Action of 25 September 1917

On 25 September, a German attack on the front of the 20th (Light) Division (XIV Corps) was prevented by artillery fire but on the X Corps front, south of I Anzac Corps, a bigger German attack took place.[37] Crown Prince Rupprecht had ordered the attack to recover ground on the Gheluvelt Plateau and to try to gain time for reinforcements to be brought into the battle zone.[38] Two regiments of the 50th Reserve Division attacked either side of the Reutelbeek, with the support of 44 field and 20 heavy batteries of artillery, four times the usual amount of artillery for one division.[39] The attack was made on a 1,800 yd (1,600 m) front, from the Menin road to Polygon Wood, to recapture pillboxes and shelters in the Wilhelmstellung 500 yd (460 m) away. The German infantry had been due to advance at 5:15 a.m. but the barrage fell short and the German infantry had to fall back until it began to creep forward at 5:30 a.m.[39] The German infantry managed to advance on the flanks, about 100 yd (91 m) near the Menin road and 600 yd (550 m) north of the Reutelbeek, close to Black Watch Corner, with the help of a number of observation and ground-attack aircraft and a box-barrage, which obstructed the supply of ammunition to the British defenders. Return-fire from the 33rd Division troops under attack and the 15th Australian Brigade along the southern edge of Polygon wood, forced the Germans under cover after they had recaptured several pillboxes near Black Watch Corner.[40]

Battle

Second Army

In X Corps, the 19th (Western) Division of IX Corps provided flanking artillery fire, machine-gun fire and a smoke screen for the 39th Division, keeping a very thinly occupied front line, which received much German retaliatory artillery fire at first, which fell on unoccupied ground, then diminished and became inaccurate during the day.[41] The 39th Division attacked at 5:50 a.m. on 26 September with two brigades. The "Quadrilateral" further down Bassevillebeek spur, which commanding the area around Tower Hamlets was captured; the right brigade had been caught in the boggy ground of the Bassevillebeek and its two tanks in support got stuck near Dumbarton Lakes. Soon after arriving in the "Quadrilateral" it was counter-attacked by part of the German 25th Division and pushed back 200 yd (180 m).[42] The left brigade passed through Tower Hamlets to reach the final objective and consolidated behind Tower Trench, with an advanced post in the north-west of Gheluvelt Wood.[43]

The right brigade of the 33rd Division advanced to recapture the ground lost in the German attack the day before and was stopped 50 yd (46 m) short of its objective, until a reserve company assisted and gained touch with the left brigade of the 39th Division to the south. On the left of the brigade the old front line was regained by 1:30 p.m. and posts established beyond the Reutelbeek.[44] The 98th Brigade on the left attacked with reinforcements from the reserve brigade at 5:15 a.m. so as to advance 500 yd (460 m) with the troops at Black Watch Corner in action the previous day. At 2:20 a.m. the brigade had gained Jerk House and met the 5th Australian Division to the north. A German barrage forced a delay until 5:30 a.m. but the German bombardment increased in intensity and the advance lost the barrage, reaching only as far as Black Watch Corner. A reserve battalion was sent through the 5th Australian Division sector, to attack to the south-east at noon, which enabled the brigade to regain most of the ground lost the day before, although well short of the day's objectives. A German counter-attack at 2:30 p.m. was driven off and more ground re-taken by the 100th Brigade on the right. A pillbox near the Menin road taken at 4:00 p.m. was the last part of the area captured by the German attack the previous day to be re-taken. A German counter-attack at 5:00 p.m. was stopped by artillery fire.[45]

I Anzac Corps attacked with the 5th Australian Division on the right. In the 15th Australian Brigade the battalions were to advance successively but bunched up near the first objective and were stopped by pillboxes at the "racecourse" and fire from the 33rd Division area to the south. At 7:30 a.m. the right-hand battalion dug in at the boundary with the 33rd Division and the other two advanced to the second objective by 11:00 a.m. The left brigade assembled in twelve waves on a strip of ground 60 yd (55 m) deep and avoided the German barrage fired at 4:00 a.m. which fell behind them and advanced through the fog 500 yd (460 m) almost unopposed to The Butte. At some pillboxes there was resistance but many German soldiers surrendered when they were rapidly surrounded.[46] The Butte was rushed and was found to be full of German dugouts.[47] Two battalions passed through at 7:30 a.m. towards the second objective, a 1,000 yd (910 m) stretch of the Flandern I Stellung and some pillboxes, until held up by fire from a German battalion headquarters on the Polygonebeek. A reserve battalion overran the dugouts and more pillboxes nearby, advancing to just beyond the final objective, at the junction with the 4th Australian Division to the north, taking 200 prisoners and 34 machine-guns. An attempted German counter-attack by part of the 17th Division was dispersed by artillery and machine-gun fire.[48][49]

The 4th Australian Division assembled well forward and avoided the German barrage by squeezing up into an area 150 yd (140 m) deep and attacked at 6:45 a.m. with two brigades. The right brigade attacked through a mist, took the first objective with only short delays to capture pillboxes but then mistakenly advanced into the standing barrage, which had paused for twice as long as usual, to assist the 3rd Division advance through muddier conditions to the north and had to be brought back until the barrage moved forward. The brigade reached the final objective from just short of the Flandern I Stellung on the right and the edge of Zonnebeke on the left and gained touch with the 5th Australian Division further south. At 1:20 p.m. air reconnaissance reported German troops east of Broodseinde ridge and at 3:25 p.m. as the German force from the 236th Division, massed to counter-attack it was dispersed by artillery fire. The northern brigade advanced to the final objective against minor opposition, moving beyond the objective to join with the 3rd Division to the north, which had pressed on into Zonnebeke. Attempts by the Germans to counter-attack at 4:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. were stopped by the protective barrage and machine-gun fire.[50][51]

Fifth Army

The southern boundary of the Fifth Army lay about 800 yd (730 m) south of the Ypres–Roulers railway, in the V Corps area. The 3rd Division attacked either side of the line at 5:50 a.m. The right brigade met little resistance but was briefly held up when crossing the Steenbeek. The advance slowed under machine-gun fire from Zonnebeke station on the far side of the railway as troops entered Zonnebeke. North of the embankment, the left brigade attacked at 5:30 a.m. in a mist and reached the first objective, despite crossing severely boggy ground, at 7:00 a.m. The advance resumed and reached the western slope of Hill 40, just short of the final objective. A German counter-attack began at 2:30 p.m. but was stopped easily. A bigger attempt at 6:30 p.m. was defeated with rifle and machine-gun fire, as the British attack on Hill 40 resumed, eventually leaving both sides still on the western slope.[52]

The 59th (2nd North Midland) Division attacked with two brigades, the right brigade advancing until held up by its own barrage, to take Dochy Farm at 7:50 a.m. One battalion found a German barrage laid behind the British creeping barrage, creeping back with it, causing many casualties.[53] The advance continued beyond the final objective to Riverside and Otto farms but when the protective barrage fell short, Riverside was abandoned. The left brigade advanced and took Schuler Farm, Cross Cottages, Kansas, Martha, Green and Road Houses then Kansas Cross and Focker pillboxes. As the brigade reached the final objective, Riverside, Toronto and Deuce Houses were captured. A German counter-attack between 5:30 p.m. and 6:50 p.m. pushed back some advanced posts, which with reinforcements were regained by 11:00 p.m.[52]

In the XVIII Corps area, the 58th (2/1st London) Division attacked with one brigade at 5:50 a.m. In a thick mist some of the British troops lost direction and were then held up by fire from Dom Trench and a pillbox but after these were captured, the advance resumed until stopped at Dear House, Aviatik Farm and Vale House, about 400 yd (370 m) short of the final objective. A German counter-attack pushed the British back from Aviatik Farm and Dale House and an attempt to regain them failed. Another attack at 6:11 p.m. reached Nile on the divisional boundary with the 3rd Division. German troops trickling forward to Riverside and Otto pillboxes were stopped by artillery and machine-gun fire.[54]

Air operations

Aircraft of the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) flew over the infantry on contact patrol, the aeroplanes being distinguished by black streamers on the rear edge of their left wings. The crews called for signals from the ground by sounding a klaxon horn or dropping lights, to which infantry responded with red flares to communicate their position to be reported to the Australian divisional headquarters.[46] The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) began operations on the night of 25–26 September when 100 and 101 squadrons attacked German billets and railway stations. Mist rose before dawn and ended night flying early; low cloud was present at 5:50 a.m. when the infantry advanced, which made observation difficult. Contact-patrol and artillery-observers could see the ground and reported 193 German artillery batteries to British artillery. Fighters flying at about 300 ft (91 m) attacked German infantry and artillery; German aircraft tried the same tactic against British troops with some success, although five were shot down by ground fire. Six German aircraft were shot down by RFC and Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) pilots over the battlefield.[55] Operations further afield were reduced due to the low cloud but three German airfields were attacked and an offensive patrol over the front line intercepted German bombers and escorts and drove them off.[56]

German 4th Army

Despite difficulties at the extremities of the attack front, by mid-morning most British objectives had been gained and consolidated. The Germans launched several counter-attacks, with the Eingreif divisions supported by the equivalent of ten normal divisional artilleries.[36] Clearing weather assisted early observation of the German counter-attacks, most of which were repulsed by accurate, heavy, medium and field artillery and small-arms fire, causing many German casualties.[57] At Zonnebeke a local counter-attack by the 34th Fusilier Regiment (3rd Reserve Division) was attempted around 6:45 a.m., with part of the 2nd battalion (in support) advancing to reinforce the 3rd Battalion holding the front line and the reserve battalion (1st) joining the counter-attack, after advancing west over Broodseinde ridge.[58] The order reached the troops south of the Ypres–Roulers railway quickly, who attacked immediately. The companies south of Zonnebeke advanced and were overrun by British troops on the Grote Molen spur and taken prisoner.[59]

Closer to the railway, troops reached the lake near Zonnebeke church and were pinned down by a British machine-gun already dug-in nearby. The order to counter-attack was slow to arrive north of the railway and did not begin until I Battalion (in reserve) arrived. The battalion was able to descend the slope from Broodseinde covered by mist and smoke, which led to few losses but some units losing direction. The British barrage near the village caused many casualties but the survivors pressed on through it and at 7:30 a.m. reached the remnants of the 3rd Battalion near the level crossing north of the village, just in time to hold off a renewed British attack 200 yd (180 m) short of their position, as stray German troops trickled in. By mid-morning the mist had cleared, allowing German machine-gunners and artillery to pin the British down around Grote Molen spur and Frezenburg ridge, forestalling a British attack intended for 10:00 a.m..[59]

Around noon, British aircraft on counter-attack patrol began to send wireless messages warning of German infantry advancing towards the front that had been attacked. Similar reports from the ground began in the early afternoon. In the centre German infantry from the 236th Division, 234th Division and 4th Bavarian Division were advancing north of Becelaere–Broodseinde–Passchendaele Ridge, while the 17th Division advanced south of Polygon wood.[60] British artillery immediately bombarded these areas, disrupting the German deployment and causing the German attacks to be disjointed. A German officer later wrote of severe delays and disorganisation caused to German Eingreif units by British artillery-fire and air attacks.[61] A counter-attack either side of Molenaarelsthoek was stopped dead at 3:25 p.m. At 4:00 p.m. German troops advancing around Reutel to the south were heavily bombarded, as were German artillery positions in Holle Bosch, ending the German advance. A German attack then developed near Polderhoek, whose survivors managed to reach the British infantry and were seen off in bayonet fighting. Observation aircraft found German troops massing against Tower Hamlets, on the Bassevillebeek spur and artillery and machine-gun barrages stopped the attack before it reached the British infantry.[62]

At 6:50 p.m. the Germans managed to organise an attack from Tower Hamlets to north of Polygon Wood; such German infantry as got through the barrages were "annihilated" by the British infantry.[62] German counter-attacks were only able to reach the new front line and reinforce the remnants of the front divisions.[63] The 236th Division (Eingreif) attacked south of the Ypres–Roulers railway and 4th Bavarian Division (Eingreif) for 2,000 yd (1,800 m) to the north, with field artillery and twelve aircraft attached to each division and the 234th Division in support.[64] British counter-attack patrols easily observed the advance and as the lines of German troops breasted Broodseinde ridge at 2:30 p.m., a huge bombardment enveloped them. German field artillery with the infantry was hit by artillery-fire, which blocked the roads, causing delays and disorganisation. German infantry had many casualties, as they advanced down the slope in good visibility. The 236th Division lost so many men that it was only able to reinforce the troops of the 3rd Reserve Division, found east of the Zonnebeke–Haus Kathé road on Grote Molen spur, chasing a few Australian souvenir hunters out of Molenaarelsthoek.[65]

The 4th Bavarian Division had to find a way across the mud of the Paddebeek, east of Kleinmolen Spur and suffered 1,340 casualties to reach the survivors of the 3rd Reserve Division from Polygon Wood to Kleinmolen) and the 23rd Reserve Division from Kleinmolen to St Julien. A British attack at 6:00 p.m. and the German counter-attack over Hill 40 and Kleinmolen coincided and both sides ended where they began.[66] The Eingreif units took up to two hours to cover one kilometre through the British barrages and arrived exhausted. The 17th Division had replaced the 16th Bavarian Division as the Eingreif division covering Zandvoorde, just before the battle. At 10:00 a.m. parts of the division advanced north-west towards Terhand and met the first layer of the British barrage, delaying the arrival of advanced units at their assembly areas until 1:00 p.m. Orders to advance took until 2:00 p.m. to arrive and the troops moved through crater fields and the British bombardment, dispersing to avoid swamps and the worst of the British artillery fire. Polderhoek was reached at 4:10 p.m. but the troops were skylined near Polderhoek Château and hit by artillery and machine-gun fire from three sides; the counter-attack "withered away".[67] A lull began at 8:30 p.m. and after a quiet night, British and Australian troops occupied Cameron House and the head of the Reutelbeek valley, near Cameron Covert.[68]

27–29 September

On 27 September in the X Corps area on the right flank, south of the Menin road, the 39th Division stopped three German counter-attacks against Tower Hamlets Spur with artillery fire and on the night of 27/28 September, the division was relieved by the 37th Division. In the 33rd Division area, after a report that Cameron House had been captured by the Australians, a battalion of the 98th Brigade to the north, attacked towards the 5th Australian Division against determined German resistance, reaching the Australians at Cameron Covert at 3:50 p.m. That night, the 33rd Division was relieved by the 23rd Division, which had received only two days' rest. On the morning of 27 September, the 76th Brigade and the 8th Brigade of the 3rd Division, east of Zonnebeke in the V Corps area, received orders to push on to the blue line atop Hill 40 but the attack failed. The 9th Brigade was ordered to complete the task on the evening of 28 September but at 6:35 p-m. on 27 September, a German barrage fell on the positions of the division, especially at Hill 40. The 3rd Division repulsed a determined German attack with artillery, machine-gun and rifle-fire after severe fighting, particularly around Bostin Farm but the division, including the 9th Brigade, suffered many casualties to German artillery-fire and the attack due on 28 September was called off, since the reverse slope position on the west side of Hill 40 was more sheltered than the blue line along the top of the hill and was a suitable jumping-off line for the next attack.[69][lower-alpha 4] At least seven counter-attacks had been made by the Germans on 27 September and another seven had followed the next day.[71]

Aftermath

Analysis

Each of the three German ground-holding divisions attacked on 26 September had an Eingreif division in support, which was twice the ratio of 20 September. No ground captured by the British had been regained and the counter-attacks had managed only to reach ground held by the remnants of the front-line divisions. The German official historians recorded that the German counter-attacks found well-dug-in (eingenistete) infantry and in places, more British attacks.[68] Albrecht von Thaer, the Chief of Staff of Gruppe Wijtschate (the XII Saxon Corps headquarters) made a diary entry on 28 September that "We are living through truly abominable days" and that he had no idea what to do about the British limited-objective attacks and their devastating artillery support.[72]

The British infantry had advanced over the "field of corpses" with few casualties and dug in. German counter-attacks had advanced through the British artillery-fire only to meet massed machine-gun fire and "collapse[d] in ruins". Thaer wrote that reinforcing the front line would only present more men to be annihilated but the practice of keeping them back for counter-attacks had been thwarted. Only masses of tanks could help but the German army had none; Loßberg did not know what to do and Ludendorff had no panacea either.[72] For the first time, the number of divisions in the 4th Army was increased but ammunition consumption was unsustainable; even on quiet days, the 4th Army fired more shells than daily receipts of the army group and on days like 20 September, consumption doubled. On 28 September, Hindenburg decided to revert to holding the front line in more strength to resist an attack and to conduct Gegenangriffe after the British attack, rather than persist with futile and costly Gegenstoße; Loßberg issued new orders to the 4th Army on 30 September.[73]

Second Army Intelligence estimated that ten divisional artilleries had supported the German troops defending the Gheluvelt Plateau, doubling the Royal Artillery casualties compared to the previous week.[36] Major-General Charles (Tim) Harington, the Second Army chief of staff, warned in a memorandum that the maximum effort made by the 4th Army to hold ground between the Menin road and Zonnebeke, demonstrated the vital importance of the ground to the German defence. Another German attack on Tower Hamlets was spotted assembling and deluged with artillery-fire during the night of 26/27 September and repulsed. The effort made by the Germans to hold the ground captured on 25 September at the Reutelbeek and south of Polygon Wood showed the importance of the upper ends of the valley between Becelaere and Gheluvelt. The 3rd Reserve Division had experienced desertions and refusals of orders, the 50th Reserve Division was also thought to have suffered such casualties that the divisions would be relieved and that two divisions involved in the counter-attacks of 25 September had also suffered severely. The Germans could be expected to defend the Zandvoorde Ridge north of Becelaere with even greater determination to prevent the British from gaining observation over the assembly areas beyond it to the east.[74]

Casualties

The British had 15,375 casualties; 1,215 being killed. In the Second army, the 39th Division suffered 1,577 casualties on 26 September, the 33rd Division 2,905, 444 being killed, the 4th Australian Division suffered 1,529 casualties (1,717 according to Charles Bean, the Australian official historian, in 1941) the 5th Australian Division had 3,723 casualties (4,014 killed and wounded from 26–28 September according to Bean).[75][31] In the Fifth Army, the 3rd Division had 4,032 casualties, 497 killed, the 59th Division 1,110, 176 killed and the 58th Division 499 casualties, of whom 98 were killed.[75] From 20 to 27 September, the 236th (Eingreif) Division suffered 1,227 casualties, the 234th Division had 1,850 casualties, the 10th Ersatz Division 672, the 50th Reserve Division 1,850 and the 23rd Reserve (Eingreif) Division 2,119 casualties. The 3rd Reserve Division, 17th (Eingreif) Division, 19th Reserve Division and 4th Bavarian (Eingreif) Division casualties are unknown; Gruppe Ypern suffered 25,089 casualties in September.[76][75] In Der Weltkrieg the German official historians recorded 13,500 casualties from 21–30 September, to which James Edmonds, the British official historian, controversially added 30 percent for lightly wounded in the second 1917 volume of History of the Great War (1948).[77]

Subsequent operations

A lull followed until 30 September, when a morning attack by regiments of the fresh 8th and 45th Reserve divisions and the 4th Army Sturmbattalion, with flame-throwers and a smoke screen, on the 23rd Division (X Corps) front, north of the Menin road was defeated.[78] Another German attempt at 5.30 a.m. on 1 October, with support from ground-attack aircraft, pushed two battalions back 150 yd (140 m); three later attacks were repulsed. Further north the Germans attacked the 7th Division at 6:15 a.m. and were stopped by artillery and small arms fire. A renewed attack at 9:00 a.m. also failed and when preparations for a third attack were seen at Cameron Covert and Joist Trench, an artillery bombardment stopped all activity. Joist Farm was lost by the 21st Division during a German attack on Polygon Wood and Black Watch Corner and the line stabilised east of Cameron House. German attacks near the Menin road on the 37th Division front in IX Corps and the 5th Division (X Corps) on 3 October failed.[79] On 30 September the Germans had conducted three counter-attacks, followed by five more on 1 October and another two on 3 October.[71]

Commemoration

Though smaller than in 1917, Polygon Wood is still a large feature; the remains of three German pillboxes captured by the Australians lie deep among the trees but few trench lines remain. The Butte is still prominent and mounted on top of it is the 5th Australian Division memorial. There are two Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries in the vicinity of Polygon Wood, the CWGC Polygon Wood Cemetery and the CWGC Buttes New British Cemetery. Within Buttes New British Cemetery is the CWGC New Zealand Memorial to the Missing.[80]

Notes

- The name Polygon Wood (German-Polygonwald or French-Bois de Polygone) was derived from the shape of a plantation forest that lay along the axis of the Australian advance on 26 September 1917. The wood was sometimes known as Racecourse Wood, as there was a track within it. Before the Great War, Polygon Wood was used by the Belgian Army and within it stands a large mound, known as the Butte, which was used as a rifle range; there was also a small airfield near the area.[1]

- From 28 August – 12 September, 240 field guns and howitzers, 386 medium and heavy guns and howitzers arrived from the Third and Fourth armies.[7]

- Several writers have followed the official historian, James Edmonds (1991 [1948]) in ascribing these changes to the influence of Plumer and the Second Army staff, once Haig had transferred the main offensive effort from the Fifth Army, in late August.[20] The narrative of the Official History makes it clear that the Fifth Army methods used in July and August and those of the Second Army from September to the end of the battle were similar and that the changes were incremental.[21] The practice of troops behind the leading infantry moving in artillery formation or columns had been used on 31 July at the Battle of Pilckem Ridge. The Capture of Westhoek on 10 May and the Battle of Langemarck (16–18 August) were strictly limited attacks, on the fronts of the II and XIX corps, to reach the black and green lines (second and third objectives) of the 31 July attack.[22]

- On 28 September, XVIII Corps relieved the 58th Division with the 48th Division and in XIV Corps the 29th Division took over from the 20th Division.[70]

Footnotes

- Gibbs 2009, p. 359.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 290.

- Sheldon 2007, pp. 185–186.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 24–25.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 95–96.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 183–213.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 244.

- Terraine 1977, p. 257.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 239–242, 452–464.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 253–279.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 280–289, 290–295.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 168–170.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 69–82.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 280.

- Bean 1941, pp. 791–796.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 282.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 284.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 456–459.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 183–213, 449–452; Davidson 2010, pp. 44–48.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 239; Liddle 1997, pp. 37, 52–54, 111–112, 233; Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 113–114; Sheffield & Todman 2004, pp. 126–127, 182–184.

- Simpson 2001, pp. 133–136.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 81; Edmonds 1991, pp. 184–202.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 459–464.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 240–242.

- Bond 1999, pp. 85–86.

- Bewsher 1921, pp. 200–201.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 459.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 460–461.

- Ewing 2001, p. 237.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 281.

- Bean 1941, p. 795.

- Wynne 1976, p. 284.

- Lupfer 1981, p. 14.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 295.

- Rogers 2010, pp. 169–170.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 293.

- Moorhouse 2003, pp. 174–175; Bean 1941, pp. 799–809.

- Sheldon 2007, p. 166; Edmonds 1991, p. 283.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 283.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 283; Bean 1941, p. 794; Sheldon 2007, p. 167.

- Wyrall 2009, p. 118.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 288.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 82–83.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 83–84.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 83–85.

- Ellis 1920, p. 245.

- Bean 1941, p. 826.

- Bean 1941, pp. 826–827.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 85–87.

- Bean 1941, pp. 829, 830.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 87–89.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 89–92.

- Oates 2010, p. 167.

- McCarthy 1995, p. 93.

- Jones 2002, pp. 191–192.

- Jones 2002, pp. 193–194.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 290–293.

- Rogers 2010, p. 172.

- Rogers 2010, p. 173.

- Bean 1941, p. 823.

- Sheldon 2007, pp. 167–168.

- Sheldon 2007, p. 173.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 291–292.

- Rogers 2010, p. 174.

- Bean 1941, p. 830.

- Rogers 2010, p. 175.

- Sheldon 2007, pp. 169–171.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 292.

- Perry 2014, pp. 340–341.

- Perry 2014, p. 341.

- Terraine 1977, p. 278.

- Lloyd 2017, pp. 200–201.

- Boff 2018, p. 179.

- Harington 2017, pp. 117–119.

- Perry 2014, p. 346.

- USWD 1920.

- Reichsarchiv 1942, p. 96; Edmonds 1991, p. 293; McRandle & Quirk 2006, pp. 667–701.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 302.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 93–96.

- Bean 1941, p. 794.

References

Books

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941) [1933]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. IV (1941 ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-7022-1710-4. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Bewsher, F. W. (1921). The History of the 51st (Highland) Division 1914–1918 (online ed.). London: Blackwood. OCLC 3499483. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Boff, J. (2018). Haig's Enemy: Crown Prince Rupprecht and Germany's War on the Western Front (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967046-8.

- Bond, B., ed. (1999). Look To Your Front: Studies in the First World War. Kent: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-065-7.

- Davidson, Sir J. (2010) [1953]. Haig : Master of the Field. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-184884-362-2.

- Die Kriegführung im Sommer und Herbst 1917. Die Ereignisse außerhalb der Westfront bis November 1918. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande. XIII (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. 1942. OCLC 257129831. Retrieved 17 November 2012 – via Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Ellis, A. D. (1920). The Story of the Fifth Australian Division, Being an Authoritative Account of the Division's Doings in Egypt, France and Belgium. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 464115474. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Ewing, J. (2001) [1921]. The History of the Ninth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-1-84342-190-0. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Gibbs, P. (2009) [1918]. From Bapaume to Passchendaele, The Western Front, 1917 (Kessinger Publishing ed.). New York: G. H. Doran. ISBN 978-1-120-28395-5. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Harington, C. (2017) [1935]. Plumer of Messines (facsimile pbk. Gyan Books, India ed.). London: John Murray. OCLC 186736178.

- Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War (1914–1918). Document (United States. War Department) No. 905. Washington D.C.: United States Army, American Expeditionary Forces, Intelligence Section. 1920. OCLC 565067054. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1934]. The War in the Air: Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. IV (Naval & Military Press ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-415-4. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Liddle, P. H., ed. (1997). Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third Battle of Ypres. London: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-588-5.

- Lloyd, N. (2017). Passchendaele: A New History. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-241-00436-4.

- Lupfer, T. (1981). The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Change in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War (PDF). Fort Leavenworth: US Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 8189258. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- McCarthy, C. (1995). The Third Ypres: Passchendaele, the Day-By-Day Account. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-217-5.

- Moorhouse, B. (2003). Forged By Fire: The Battle Tactics and Soldiers of a World War One Battalion, The 7th Somerset Light Infantry. Kent: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-191-3.

- Oates, W. C. (2010) [1920]. The Sherwood Foresters in the Great War: The 2/8th Battalion (Nabu Press ed.). Nottingham: Bell. ISBN 978-1-172-60270-4.

- Perry, R. A. (2014). To Play a Giant's Part: The Role of the British Army at Passchendaele (1st ed.). Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-78331-146-0.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (1996). Passchendaele: The Untold Story. Cumberland: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-172-60270-4.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-90603-376-7.

- Sheffield, G.; Todman, D. (2004). Command and Control on the Western Front: The British Army's Experience 1914–18. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-083-1.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. London: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-564-4.

- Terraine, J. (1977). The Road to Passchendaele: The Flanders Offensive 1917, A Study in Inevitability. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-436-51732-7.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

- Wyrall, E. (2009) [1932]. The Nineteenth Division 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-1-84342-208-2.

Journals

- McRandle, J. H.; Quirk, J. (2006). "The Blood Test Revisited: A New Look at German Casualty Counts in World War I". The Journal of Military History. Lexington Va. 70 (3 July 2006): 667–701. doi:10.1353/jmh.2006.0180. ISSN 0899-3718.

Theses

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (PhD). London: London University. OCLC 557496951. uk.bl.ethos.367588. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

Further reading

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (repr. London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 978-0-948130-18-2.

- Rawson, A. (2017). The Passchendaele Campaign 1917 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-52670-400-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Polygon Wood. |

- Order of Battle – France and Flanders 1917, Battle # 98 – Order of Battle for the Battle of Polygon Wood

- Historical facts on WWI in the Ypres region: Australian Embassy and Mission to the European Communities

- Sketch of the German Butte de Polygon defences

- Battle of Polygon Wood, 26 September 1917

- Battle of Polygon Wood

- YouTube video of Polygon Wood