Austria-Hungary

Austria–Hungary, often referred to as the Austro–Hungarian Empire or the Dual Monarchy, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe[lower-alpha 1] between 1867 and 1918.[6][7] It was formed with the Austro–Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and was dissolved following its defeat in the First World War.

Austro-Hungarian Monarchy | |

|---|---|

| 1867–1918 | |

Medium coat of arms

(1867–1915) | |

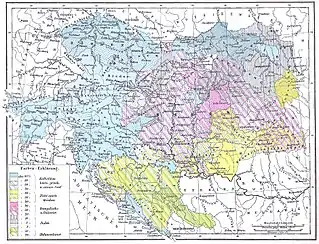

.svg.png.webp) Austria–Hungary on the eve of World War I | |

| Capital | Vienna[1] (Cisleithania) Budapest (Transleithania) |

| Official languages |

Other spoken languages: Bosnian, Czech, Romani (Carpathian), Italian, Istro-Romanian, Polish, Romanian, Rusyn, Ruthenian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovene, Yiddish[3] |

| Religion | 76.6% Catholic (incl. 64–66% Roman & 10–12% Eastern) 8.9% Protestant (Lutheran, Reformed, Unitarian) 8.7% Orthodox 4.4% Jewish 1.3% Muslim (1910 census[4]) |

| Demonym(s) | Austro-Hungarian |

| Government | Constitutional dual monarchy |

| Emperor-King | |

• 1867–1916 | Franz Joseph I |

• 1916–1918 | Karl I & IV |

| Minister-President of Austria | |

• 1867 (first) | F. F. von Beust |

• 1918 (last) | Heinrich Lammasch |

| Prime Minister of Hungary | |

• 1867–1871 (first) | Gyula Andrássy |

• 1918 (last) | János Hadik |

| Legislature | 2 national legislatures |

| Herrenhaus Abgeordnetenhaus | |

| House of Magnates House of Representatives | |

| Historical era | New Imperialism • World War I |

| 30 March 1867 | |

| 7 October 1879 | |

| 6 October 1908 | |

| 28 June 1914 | |

| 28 July 1914 | |

| 31 October 1918 | |

| 12 November 1918 | |

| 16 November 1918 | |

| 10 September 1919 | |

| 4 June 1920 | |

| Area | |

| 1905[5] | 621,537.58 km2 (239,977.00 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1914 | 52,800,000 |

| Currency | |

It was a real union between two monarchies, the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. A third component of the union was the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, an autonomous region under the Hungarian crown, which negotiated the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement in 1868. From 1878 Austria–Hungary jointly governed Bosnia-Hercegovina, which it annexed in 1908. Austria–Hungary was ruled by the House of Habsburg and constituted the last phase in the constitutional evolution of the Habsburg Monarchy. The union was established by the Austro–Hungarian Compromise on 30 March 1867 in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War. Following the 1867 reforms, the Austrian and Hungarian states were co-equal in power. The two states conducted common foreign, defense, and financial policies, but all other governmental faculties were divided between respective states.

Austria–Hungary was a multinational state and one of Europe's major powers at the time. Austria–Hungary was geographically the second-largest country in Europe after the Russian Empire, at 621,538 km2 (239,977 sq mi)[8] and the third-most populous (after Russia and the German Empire). The Empire built up the fourth-largest machine building industry in the world, after the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom.[9] Austria–Hungary also became the world's third-largest manufacturer and exporter of electric home appliances, electric industrial appliances, and power generation apparatus for power plants, after the United States and the German Empire.[10][11]

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise remained bitterly unpopular among the ethnic Hungarian voters[12] because ethnic Hungarians did not vote for the ruling pro-compromise parties in the Hungarian parliamentary elections. Therefore, the political maintenance of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise (thus Austria–Hungary itself) was mostly a result of the popularity of the pro-compromise ruling Liberal Party among the ethnic minority voters in the Kingdom of Hungary.

After 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina came under Austro-Hungarian military and civilian rule[13] until it was fully annexed in 1908, provoking the Bosnian crisis among the other powers.[14] The northern part of the Ottoman Sanjak of Novi Pazar was also under de facto joint occupation during that period, but the Austro-Hungarian army withdrew as part of their annexation of Bosnia.[15] The annexation of Bosnia also led to Islam being recognized as an official state religion due to Bosnia's Muslim population.[16]

Austria–Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. It was already effectively dissolved by the time the military authorities signed the armistice of Villa Giusti on 3 November 1918. The Kingdom of Hungary and the First Austrian Republic were treated as its successors de jure, whereas the independence of the West Slavs and South Slavs of the Empire as the First Czechoslovak Republic, the Second Polish Republic, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, respectively, and most of the territorial demands of the Kingdom of Romania were also recognized by the victorious powers in 1920.

Creation

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Austria |

|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Hungary |

|

|

|

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (called the Ausgleich in German and the Kiegyezés in Hungarian), which inaugurated the empire's dual structure in place of the former Austrian Empire (1804–1867), originated at a time when Austria had declined in strength and in power—both in the Italian Peninsula (as a result of the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859) and among the states of the German Confederation (it had been surpassed by Prussia as the dominant German-speaking power following the Austro-Prussian War of 1866).[17] The Compromise re-established[18] the full sovereignty of the Kingdom of Hungary, which was lost after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

Other factors in the constitutional changes were continued Hungarian dissatisfaction with rule from Vienna and increasing national consciousness on the part of other nationalities (or ethnicities) of the Austrian Empire. Hungarian dissatisfaction arose partly from Austria's suppression with Russian support of the Hungarian liberal revolution of 1848–49. However, dissatisfaction with Austrian rule had grown for many years within Hungary and had many other causes.

By the late 1850s, a large number of Hungarians who had supported the 1848–49 revolution were willing to accept the Habsburg monarchy. They argued that while Hungary had the right to full internal independence, under the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, foreign affairs and defense were "common" to both Austria and Hungary.[19]

After the Austrian defeat at Königgrätz, the government realized it needed to reconcile with Hungary to regain the status of a great power. The new foreign minister, Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust, wanted to conclude the stalemated negotiations with the Hungarians. To secure the monarchy, Emperor Franz Joseph began negotiations for a compromise with the Hungarian nobility, led by Ferenc Deák. On 20 March 1867, the re-established Hungarian parliament at Pest started to negotiate the new laws to be accepted on 30 March. However, Hungarian leaders received the Emperor's coronation as King of Hungary on 8 June as a necessity for the laws to be enacted within the lands of the Holy Crown of Hungary.[19] On 28 July, Franz Joseph, in his new capacity as King of Hungary, approved and promulgated the new laws, which officially gave birth to the Dual Monarchy.

Name and terminology

The realm's official name was in German: Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie and in Hungarian: Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia (English: Austro-Hungarian Monarchy),[20] though in international relations Austria–Hungary was used (German: Österreich-Ungarn; Hungarian: Ausztria-Magyarország). The Austrians also used the names k. u. k. Monarchie (English: k. u. k. monarchy)[21] (in detail German: Kaiserliche und königliche Monarchie Österreich-Ungarn; Hungarian: Császári és Királyi Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia)[22] and Danubian Monarchy (German: Donaumonarchie; Hungarian: Dunai Monarchia) or Dual Monarchy (German: Doppel-Monarchie; Hungarian: Dual-Monarchia) and The Double Eagle (German: Der Doppel-Adler; Hungarian: Kétsas), but none of these became widespread either in Hungary, or elsewhere.

The realm's full name used in the internal administration was The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen.

- German: Die im Reichsrat vertretenen Königreiche und Länder und die Länder der Heiligen Ungarischen Stephanskrone

- Hungarian: A Birodalmi Tanácsban képviselt királyságok és országok és a Magyar Szent Korona országai

From 1867 onwards, the abbreviations heading the names of official institutions in Austria–Hungary reflected their responsibility:

- k. u. k. (kaiserlich und königlich or Imperial and Royal) was the label for institutions common to both parts of the Monarchy, e.g., the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine (War Fleet) and, during the war, the k.u.k. Armee (Army). The common army changed its label from k.k. to k.u.k. only in 1889 at the request of the Hungarian government.

- K. k. (kaiserlich-königlich) or Imperial-Royal was the term for institutions of Cisleithania (Austria); "royal" in this label referred to the Crown of Bohemia.

- K. u. (königlich-ungarisch) or M. k. (Magyar királyi) ("Royal Hungarian") referred to Transleithania, the lands of the Hungarian crown. In the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia, its autonomous institutions hold k. (kraljevski) ("Royal") as according to the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement, the only official language in Croatia and Slavonia was Croatian, and those institutions were "only" Croatian.

Following a decision of Franz Joseph I in 1868, the realm bore the official name Austro-Hungarian Monarchy/Realm (German: Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie/Reich; Hungarian: Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia/Birodalom) in its international relations. It was often contracted to the Dual Monarchy in English or simply referred to as Austria.[23]

Structure

The Compromise turned the Habsburg domains into a real union between the Austrian Empire ("Lands Represented in the Imperial Council", or Cisleithania)[8] in the western and northern half and the Kingdom of Hungary ("Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen", or Transleithania).[8] in the eastern half. The two halves shared a common monarch, who ruled as Emperor of Austria[24] over the western and northern half portion and as King of Hungary[24] over the eastern portion.[8] Foreign relations and defense were managed jointly, and the two countries also formed a customs union.[25] All other state functions were to be handled separately by each of the two states.

Certain regions, such as Polish Galicia within Cisleithania and Croatia within Transleithania, enjoyed autonomous status, each with its own unique governmental structures (see: Polish Autonomy in Galicia and Croatian–Hungarian Settlement).

The division between Austria and Hungary was so marked that there was no common citizenship: one was either an Austrian citizen or a Hungarian citizen, never both.[26][27] This also meant that there were always separate Austrian and Hungarian passports, never a common one.[28][29] However, neither Austrian nor Hungarian passports were used in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. Instead, the Kingdom issued its own passports, which were written in Croatian and French, and displayed the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia-Dalmatia on them.[30] Croatia-Slavonia also had executive autonomy regarding naturalization and citizenship, defined as "Hungarian-Croatian citizenship" for the kingdom's citizens.[31] It is not known what kind of passports were used in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was under the control of both Austria and Hungary.

The Kingdom of Hungary had always maintained a separate parliament, the Diet of Hungary, even after the Austrian Empire was created in 1804.[32] The administration and government of the Kingdom of Hungary (until 1848–49 Hungarian revolution) remained largely untouched by the government structure of the overarching Austrian Empire. Hungary's central government structures remained well separated from the Austrian imperial government. The country was governed by the Council of Lieutenancy of Hungary (the Gubernium) – located in Pressburg and later in Pest – and by the Hungarian Royal Court Chancellery in Vienna.[33] The Hungarian government and Hungarian parliament were suspended after the Hungarian revolution of 1848 and were reinstated after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise in 1867.

Despite Austria and Hungary sharing a common currency, they were fiscally sovereign and independent entities.[34] Since the beginnings of the personal union (from 1527), the government of the Kingdom of Hungary could preserve its separate and independent budget. After the revolution of 1848–1849, the Hungarian budget was amalgamated with the Austrian, and it was only after the Compromise of 1867 that Hungary obtained a separate budget.[35] From 1527 (the creation of the monarchic personal union) to 1851, the Kingdom of Hungary maintained its own customs controls, which separated her from the other parts of the Habsburg-ruled territories.[36] After 1867, the Austrian and Hungarian customs union agreement had to be renegotiated and stipulated every ten years. The agreements were renewed and signed by Vienna and Budapest at the end of every decade because both countries hoped to derive mutual economic benefit from the customs union. The Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary contracted their foreign commercial treaties independently of each other.[8]

Vienna served as the Monarchy's primary capital. The Cisleithanian (Austrian) part contained about 57 percent of the total population and the larger share of its economic resources, compared to the Hungarian part.

Government

There were three parts to the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire:[37]

- the common foreign, military, and a joint financial policy (only for diplomatic, military, and naval expenditures) under the monarch

- the "Austrian" or Cisleithanian government (Lands Represented in the Imperial Council)

- the "Hungarian" or Transleithanian government (Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen)

|

← common emperor-king, common ministries ← entities ← partner states | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Joint government

The common government was led by a Ministerial Council (Ministerrat für Gemeinsame Angelegenheiten), which had responsibility for the Common Army, navy, foreign policy, and the customs union.[19] It consisted of three Imperial and Royal Joint-ministries (k.u.k. gemeinsame Ministerien):

- Ministry of the Imperial and Royal Household and Foreign Affairs, known as the Imperial Chancellery before 1869;

- Imperial and Royal Ministry of War, known as the Imperial Ministry of War before 1911;

- Imperial and Royal Ministry of Finance, known as the Imperial Ministry of Finance before 1908, responsible only for the finances of the other two joint-ministries.[38]

In addition to the three ministers, the Ministerial Council also contained the prime minister of Hungary, the prime minister of Cisleithania, some Archdukes, and the monarch.[39] The Chief of the General Staff usually attended as well. The council was usually chaired by the Minister of the Household and Foreign Affairs, except when the Monarch was present. In addition to the council, the Austrian and Hungarian parliaments each elected a delegation of 60 members, who met separately and voted on the expenditures of the Ministerial Council, giving the two governments influence in the common administration. However, the ministers ultimately answered only to the monarch, who had the final decision on matters of foreign and military policy.[38]

Overlapping responsibilities between the joint ministries and the ministries of the two halves caused friction and inefficiencies.[38] The armed forces suffered particularly from the overlap. Although the unified government determined the overall military direction, the Austrian and Hungarian governments each remained in charge of recruiting, supplies and training. Each government could have a strong influence over common governmental responsibilities. Each half of the Dual Monarchy proved quite prepared to disrupt common operations to advance its own interests.[39]

Relations during the half-century after 1867 between the two parts of the dual monarchy featured repeated disputes over shared external tariff arrangements and over the financial contribution of each government to the common treasury. These matters were determined by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, in which common expenditures were allocated 70% to Austria and 30% to Hungary. This division had to be renegotiated every ten years. There was political turmoil during the build-up to each renewal of the agreement. By 1907, the Hungarian share had risen to 36.4%.[40] The disputes culminated in the early 1900s in a prolonged constitutional crisis. It was triggered by disagreement over which language to use for command in Hungarian army units and deepened by the advent to power in Budapest in April 1906 of a Hungarian nationalist coalition. Provisional renewals of the common arrangements occurred in October 1907 and in November 1917 on the basis of the status quo. The negotiations in 1917 ended with the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy.[38]

Parliaments

Hungary and Austria maintained separate parliaments, each with its own prime minister: the Diet of Hungary (commonly known as the National Assembly) and the Imperial Council in Cisleithania. Each parliament had its own executive government, appointed by the monarch. In this sense, Austria–Hungary remained under an autocratic government, as the Emperor-King appointed both Austrian and Hungarian prime ministers along with their respective cabinets. This made both governments responsible to the Emperor-King, as neither half could have a government with a program contrary to the views of the Monarch. The Emperor-King could appoint non-parliamentary governments, for example, or keep a government that did not have a parliamentary majority in power in order to block the formation of another government which he did not approve of.

The Imperial Council was a bicameral body: the upper house was the House of Lords (German: Herrenhaus), and the lower house was the House of Deputies (German: Abgeordnetenhaus). Members of the House of Deputies were elected through a system of "curiae" which weighted representation in favor of the wealthy but was progressively reformed until universal manhood suffrage was introduced in 1906.[41][42] To become law, bills had to be passed by both houses, signed by the government minister responsible and then granted royal assent by the Emperor.

The Diet of Hungary was also bicameral: the upper house was the House of Magnates (Hungarian: Főrendiház), and the lower house was the House of Representatives (Hungarian: Képviselőház). The "curia" system was also used to elect members of the House of Representatives. Franchise was very limited, with around 5% of men eligible to vote in 1874, rising to 8% at the beginning of World War I.[43] The Hungarian parliament had the power to legislate on all matters concerning Hungary, but for Croatia-Slavonia only on matters which it shared with Hungary. Matters concerning Croatia-Slavonia alone fell to the Croatian-Slavonian Diet (commonly referred to as the Croatian Parliament). The Monarch had the right to veto any kind of Bill before it was presented to the National Assembly, the right to veto all legislation passed by the National Assembly, and the power to prorogue or dissolve the Assembly and call for new elections. In practice, these powers were rarely used.

Empire of Austria (Cisleithania)

The administrative system in the Austrian Empire consisted of three levels: the central State administration, the territories (Länder), and the local communal administration. The State administration comprised all affairs having relation to rights, duties, and interests "which are common to all territories"; all other administrative tasks were left to the territories. Finally, the communes had self-government within their own sphere.

The central authorities were known as the "Ministry" (Ministerium). In 1867 the Ministerium consisted of seven ministries (Agriculture, Religion and Education, Finance, Interior, Justice, Commerce and Public Works, Defence). A Ministry of Railways was created in 1896, and the Ministry of Public Works was separated from Commerce in 1908. Ministries of Public Health and Social Welfare were established in 1917 to deal with issues arising from World War I. The ministries all had the title k.k. ("Imperial-Royal"), referring to the Imperial Crown of Austria and the Royal Crown of Bohemia.

Each of the seventeen territories had its own government, led by a Governor (officially Landeschef, but commonly called Statthalter or Landespräsident), appointed by the Emperor, to serve as his representative. Usually, a territory was equivalent to a Crown territory (Kronland), but the immense variations in area of the Crown territories meant that there were some exceptions.[44] Each territory had its own territorial assembly (Landtag) and executive (Landesausschuss). The territorial assembly and executive were led by the Landeshauptmann (i.e., territorial premier), appointed by the Emperor from the members of the territorial assembly. Many branches of the territorial administrations had great similarities with those of the State, so that their spheres of activity frequently overlapped and came into collision. This administrative "double track", as it was called, resulted largely from the origin of the State – for the most part through a voluntary union of countries that had a strong sense of their own individuality.

Below the territory was the district (Bezirk) under a district-head (Bezirkshauptmann), appointed by the State government. These district-heads united nearly all the administrative functions which were divided among the various ministries. Each district was divided into a number of municipalities (Ortsgemeinden), each with its own elected mayor (Bürgermeister). The nine statutory cities were autonomous units at the district-level.

The complexity of this system, particularly the overlap between State and territorial administration, led to moves for administrative reform. As early as 1904, premier Ernest von Koerber had declared that a complete change in the principles of administration would be essential if the machinery of State were to continue working. Richard von Bienerth's last act as Austrian premier in May 1911 was the appointment of a commission nominated by the Emperor to draw up a scheme of administrative reform. The imperial rescript did not present reforms as a matter of urgency or outline an overall philosophy for them. The continuous progress of society, it said, had made increased demands on the administration, that is to say, it was assumed that reform was required because of the changing times, not underlying problems with the administrative structure. The reform commission first occupied itself with reforms about which there was no controversy. In 1912 it published "Proposals for the training of State officials". The commission produced several further reports before its work was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. It was not till March 1918 that the Seidler Government decided upon a program of national autonomy as a basis for administrative reform, which was, however, never carried into effect.[45]

Kingdom of Hungary (Transleithania)

Executive power in Transleithania was vested in a cabinet responsible to the National Assembly, consisting of ten ministers, including: the Prime Minister, the Minister for Croatia-Slavonia, a Minister besides the King, and the Ministers of the Interior, National Defence, Religion and Public Education, Finance, Agriculture, Industry, and Trade, Public Works and Transport, and Justice. The Minister besides the King was responsible for coordination with Austria and the Imperial and royal court in Vienna. In 1889, the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade was split into separate ministries of Agriculture and Trade. The Ministry of Public Works and Transport was folded into the new Ministry of Trade.

From 1867 the administrative and political divisions of the lands belonging to the Hungarian crown were remodeled due to some restorations and other changes. In 1868 Transylvania was definitely reunited to Hungary proper, and the town and district of Fiume maintained its status as a Corpus separatum ("separate body"). The "Military Frontier" was abolished in stages between 1871 and 1881, with Banat and Šajkaška being incorporated into Hungary proper and the Croatian and Slavonian Military Frontiers joining Croatia-Slavonia.

In regard to local government, Hungary had traditionally been divided into around seventy counties (Hungarian: megyék, singular megye; Croatian: Croatian: županija) and an array of districts and cities with special statuses. This system was reformed in two stages. In 1870, most historical privileges of territorial subdivisions were abolished, but the existing names and territories were retained. At this point, there were a total of 175 territorial subdivisions: 65 counties (49 in Hungary proper, 8 in Transylvania, and 8 in Croatia), 89 cities with municipal rights, and 21 other types of municipality (3 in Hungary proper and 18 in Transylvania). In a further reform in 1876, most of the cities and other types of municipality were incorporated into the counties. The counties in Hungary were grouped into seven circuits,[35] which had no administrative function. The lowest level subdivision was the district or processus (Hungarian: szolgabírói járás).

After 1876, some urban municipalities remained independent of the counties in which they were situated. There were 26 of these urban municipalities in Hungary: Arad, Baja, Debreczen, Győr, Hódmezővásárhely, Kassa, Kecskemét, Kolozsvár, Komárom, Marosvásárhely, Nagyvárad, Pancsova, Pécs, Pozsony, Selmecz- és Bélabanya, Sopron, Szabadka, Szatmárnémeti, Szeged, Székesfehervár, Temesvár, Újvidék, Versecz, Zombor, and Budapest, the capital of the country.[35] In Croatia-Slavonia, there were four: Osijek, Varaždin and Zagreb and Zemun.[35] Fiume continued to form a separate division.

The administration of the municipalities was carried on by an official appointed by the king. These municipalities each had a council of twenty members. Counties were led by a County head (Hungarian: Ispán or Croatian: župan) appointed by the king and under the control of the Ministry of the Interior. Each county had a municipal committee of 20 members,[35] comprising 50% virilists (persons paying the highest direct taxes) and 50% elected persons fulfilling the prescribed census and ex officio members (deputy county head, main notary, and others). The powers and responsibilities of the counties were constantly decreased and were transferred to regional agencies of the kingdom's ministries.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

In 1878, the Congress of Berlin placed the Bosnia Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire under Austro-Hungarian occupation. The region was formally annexed in 1908 and was governed by Austria and Hungary jointly through the Imperial and Royal Ministry of Finance's Bosnian Office (German: Bosnische Amt). The Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina was headed by a governor (German: Landsschef), who was also the commander of the military forces based in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The executive branch was headed by a National Council, which was chaired by the governor and contained the governor's deputy and chiefs of departments. At first, the government had only three departments, administrative, financial and legislative. Later, other departments, including construction, economics, education, religion, and technical, were founded as well.[46]

The Diet of Bosnia, created in 1910, had very limited legislative powers. The main legislative power was in the hands of the emperor, the parliaments in Vienna and Budapest, and the joint-minister of finance. The Diet of Bosnia could make proposals, but they had to be approved by both parliaments in Vienna and Budapest. The Diet could only deliberate on matters that affected Bosnia and Herzegovina exclusively; decisions on armed forces, commercial and traffic connections, customs, and similar matters, were made by the parliaments in Vienna and Budapest. The Diet also had no control over the National Council or the municipal councils.[47]

The Austrian-Hungarian authorities left the Ottoman division of Bosnia and Herzegovina untouched, and only changed the names of divisional units. Thus the Bosnia Vilayet was renamed Reichsland, sanjaks were renamed Kreise (Circuits), kazas were renamed Bezirke (Districts), and nahiyahs became Exposituren.[46] There were six Kreise and 54 Bezirke.[48] The heads of the Kreises were Kreiseleiters, and the heads of the Bezirke were Bezirkesleiters.[46]

Empire of Austria

The December Constitution of 1867 restored the rule of law, independence of the judiciary, and public jury trials in Austria. The system of general courts had the same four rungs it still has today:

- District courts (Bezirksgerichte);

- Regional courts (Kreisgerichte);

- Higher regional courts (Oberlandesgerichte);

- Supreme Court (Oberster Gerichts- und Kassationshof).

Habsburg subjects would from now on be able to take the State to court should it violate their fundamental rights.[49] Since regular courts were still unable to overrule the bureaucracy, much less the legislature, these guarantees necessitated the creation of specialist courts that could:[50]

- The Administrative Court (Verwaltungsgerichtshof), stipulated by the 1867 Basic Law on Judicial Power (Staatsgrundgesetz über die richterliche Gewalt) and implemented in 1876, had the power to review the legality of administrative acts, ensuring that the executive branch remained faithful to the principle of the rule of law.

- The Imperial Court (Reichsgericht), stipulated by the Basic Law on the Creation of an Imperial Court (Staatsgrundgesetz über die Einrichtung eines Reichsgerichtes) in 1867 and implemented in 1869, decided demarcation conflicts between courts and the bureaucracy, between its constituent territories, and between individual territories and the Empire.[51][52] The Imperial Court also heard complaints of citizens who alleged to have been violated in their constitutional rights, although its powers were not cassatory: it could only vindicate the complainant by declaring the government to be in the wrong, not by actually voiding its wrongful decisions.[51][53]

- The State Court (Staatsgerichtshof) held the Emperor's ministers accountable for political misconduct committed in office.[54][55] Although the Emperor could not be taken to court, many of his decrees now depended on the relevant minister to countersign them. The double-pronged approach of making the Emperor dependent on his ministers and also making ministers criminally liable for bad outcomes would firstly enable, secondly motivate the ministers to put pressure on the monarch.[56]

Kingdom of Hungary

Judicial power was also independent of the executive in Hungary. After the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement of 1868, Croatia-Slavonia had its own independent judicial system (the Table of Seven was the court of last instance for Croatia-Slavonia with final civil and criminal jurisdiction). The judicial authorities in Hungary were:

- the district courts with single judges (458 in 1905);

- the county courts with collegiate judgeships (76 in number); to these were attached 15 jury courts for press offences. These were courts of first instance. In Croatia-Slavonia these were known as the court tables after 1874;

- Royal Tables (12 in number), which were courts of second instance, established at Budapest, Debrecen, Győr, Kassa, Kolozsvár, Marosvásárhely, Nagyvárad, Pécs, Pressburg, Szeged, Temesvár and Ban's Table at Zagreb.

- The Royal Supreme Court at Budapest, and the Supreme Court of Justice, or Table of Seven, at Zagreb, which were the highest judicial authorities. There were also a special commercial court at Budapest, a naval court at Fiume, and special army courts.[35]

Politics

The first prime minister of Hungary after the Compromise was Count Gyula Andrássy (1867–1871). The old Hungarian Constitution was restored, and Franz Joseph was crowned as King of Hungary. Andrássy next served as the Foreign Minister of Austria–Hungary (1871–1879).

The Empire relied increasingly on a cosmopolitan bureaucracy—in which Czechs played an important role—backed by loyal elements, including a large part of the German, Hungarian, Polish and Croat aristocracy.[57]

Political struggles in the Empire

The traditional aristocracy and land-based gentry class gradually faced increasingly wealthy men of the cities, who achieved wealth through trade and industrialization. The urban middle and upper class tended to seek their own power and supported progressive movements in the aftermath of revolutions in Europe.

As in the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire frequently used liberal economic policies and practices. From the 1860s, businessmen succeeded in industrializing parts of the Empire. Newly prosperous members of the bourgeoisie erected large homes and began to take prominent roles in urban life that rivaled the aristocracy's. In the early period, they encouraged the government to seek foreign investment to build up infrastructure, such as railroads, in aid of industrialization, transportation and communications, and development.

The influence of liberals in Austria, most of them ethnic Germans, weakened under the leadership of Count Eduard von Taaffe, the Austrian prime minister from 1879 to 1893. Taaffe used a coalition of clergy, conservatives and Slavic parties to weaken the liberals. In Bohemia, for example, he authorized Czech as an official language of the bureaucracy and school system, thus breaking the German speakers' monopoly on holding office. Such reforms encouraged other ethnic groups to push for greater autonomy as well. By playing nationalities off one another, the government ensured the monarchy's central role in holding together competing interest groups in an era of rapid change.

During the First World War, rising national sentiments and labour movements contributed to strikes, protests and civil unrest in the Empire. After the war, republican, national parties contributed to the disintegration and collapse of the monarchy in Austria and Hungary. Republics were established in Vienna and Budapest.[58]

Legislation to help the working class emerged from Catholic conservatives. They turned to social reform by using Swiss and German models and intervening in private industry. In Germany, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had used such policies to neutralize socialist promises. The Catholics studied the Swiss Factory Act of 1877 that limited working hours for everyone and gave maternity benefits and German laws that insured workers against industrial risks inherent in the workplace. These served as the basis for Austria's 1885 Trade Code Amendment.[59]

The Austro-Hungarian compromise and its supporters remained bitterly unpopular among the ethnic Hungarian voters, and the continuous electoral success of the pro-compromise Liberal Party frustrated many Hungarian voters. While the pro-compromise liberal parties were the most popular among ethnic minority voters, however the Slovak, Serb, and Romanian minority parties remained unpopular among the ethnic minorities. The nationalist Hungarian parties – which were supported by the overwhelming majority of ethnic Hungarian voters – remained in the opposition, except from 1906 to 1910 where the nationalist Hungarian parties were able to form government.[60]

Ethnic relations

.JPG.webp)

In July 1849, the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament proclaimed and enacted ethnic and minority rights (the next such laws were in Switzerland), but these were overturned after the Russian and Austrian armies crushed the Hungarian Revolution. After the Kingdom of Hungary reached the Compromise with the Habsburg Dynasty in 1867, one of the first acts of its restored Parliament was to pass a Law on Nationalities (Act Number XLIV of 1868). It was a liberal piece of legislation and offered extensive language and cultural rights. It did not recognize non-Hungarians to have rights to form states with any territorial autonomy.[61]

The "Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867" created the personal union of the independent states of Hungary and Austria, linked under a common monarch also having joint institutions. The Hungarian majority asserted more of their identity within the Kingdom of Hungary, and it came to conflict with some of her own minorities. The imperial power of German-speakers who controlled the Austrian half was resented by others. In addition, the emergence of nationalism in the newly independent Romania and Serbia also contributed to ethnic issues in the empire.

Article 19 of the 1867 "Basic State Act" (Staatsgrundgesetz), valid only for the Cisleithanian (Austrian) part of Austria–Hungary,[62] said:

All races of the empire have equal rights, and every race has an inviolable right to the preservation and use of its own nationality and language. The equality of all customary languages ("landesübliche Sprachen") in school, office and public life, is recognized by the state. In those territories in which several races dwell, the public and educational institutions are to be so arranged that, without applying compulsion to learn a second country language ("Landessprache"), each of the races receives the necessary means of education in its own language.[63]

The implementation of this principle led to several disputes, as it was not clear which languages could be regarded as "customary". The Germans, the traditional bureaucratic, capitalist and cultural elite, demanded the recognition of their language as a customary language in every part of the empire. German nationalists, especially in the Sudetenland (part of Bohemia), looked to Berlin in the new German Empire.[64] There was a German-speaking element in Austria proper (west of Vienna), but it did not display much sense of German nationalism. That is, it did not demand an independent state; rather it flourished by holding most of the high military and diplomatic offices in the Empire.

Italian was regarded as an old "culture language" (Kultursprache) by German intellectuals and had always been granted equal rights as an official language of the Empire, but the Germans had difficulty in accepting the Slavic languages as equal to their own. On one occasion Count A. Auersperg (Anastasius Grün) entered the Diet of Carniola carrying what he claimed to be the whole corpus of Slovene literature under his arm; this was to demonstrate that the Slovene language could not be substituted for German as the language of higher education.

The following years saw official recognition of several languages, at least in Austria. From 1867, laws awarded Croatian equal status with Italian in Dalmatia. From 1882, there was a Slovene majority in the Diet of Carniola and in the capital Laibach (Ljubljana); they replaced German with Slovene as their primary official language. Galicia designated Polish instead of German in 1869 as the customary language of government.

In Istria, the Istro-Romanians, a small ethnic group composed by around 2,600 people in the 1880s,[65] suffered severe discrimination. The Croats of the region, who formed the majority, tried to assimilate them, while the Italian minority supported them in their requests for self-determination.[66][67] In 1888, the possibility of opening the first school for the Istro-Romanians teaching in the Romanian language was discussed in the Diet of Istria. The proposal was very popular among them. The Italian deputies showed their support, but the Croat ones opposed it and tried to show that the Istro-Romanians were in fact Slavs.[68] During Austro-Hungarian rule, the Istro-Romanians lived under poverty conditions,[69] and those living in the island of Krk were fully assimilated by 1875.[70]

The language disputes were most fiercely fought in Bohemia, where the Czech speakers formed a majority and sought equal status for their language to German. The Czechs had lived primarily in Bohemia since the 6th century and German immigrants had begun settling the Bohemian periphery in the 13th century. The constitution of 1627 made the German language a second official language and equal to Czech. German speakers lost their majority in the Bohemian Diet in 1880 and became a minority to Czech speakers in the cities of Prague and Pilsen (while retaining a slight numerical majority in the city of Brno (Brünn)). The old Charles University in Prague, hitherto dominated by German speakers, was divided into German and Czech-speaking faculties in 1882.

At the same time, Hungarian dominance faced challenges from the local majorities of Romanians in Transylvania and in the eastern Banat, Slovaks in today's Slovakia, and Croats and Serbs in the crown lands of Croatia and of Dalmatia (today's Croatia), in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in the provinces known as the Vojvodina (today's northern Serbia). The Romanians and the Serbs began to agitate for union with their fellow nationalists and language speakers in the newly founded states of Romania (1859–1878) and Serbia.

Hungary's leaders were generally less willing than their Austrian counterparts to share power with their subject minorities, but they granted a large measure of autonomy to Croatia in 1868. To some extent, they modeled their relationship to that kingdom on their own compromise with Austria of the previous year. In spite of nominal autonomy, the Croatian government was an economic and administrative part of Hungary, which the Croatians resented. In the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina many advocated the idea of a trialist Austro-Hungaro-Croatian monarchy; among the supporters of the idea were Archduke Leopold Salvator, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and emperor and king Charles I who during his short reign supported the trialist idea only to be vetoed by the Hungarian government and Count Istvan Tisza. The count finally signed the trialist proclamation after heavy pressure from the king on 23 October 1918.[71]

Language was one of the most contentious issues in Austro-Hungarian politics. All governments faced difficult and divisive hurdles in deciding on the languages of government and of instruction. The minorities sought the widest opportunities for education in their own languages, as well as in the "dominant" languages—Hungarian and German. By the "Ordinance of 5 April 1897", the Austrian Prime Minister Count Kasimir Felix Badeni gave Czech equal standing with German in the internal government of Bohemia; this led to a crisis because of nationalist German agitation throughout the empire. The Crown dismissed Badeni.

The Hungarian Minority Act of 1868 gave the minorities (Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, et al.) individual (but not also communal) rights to use their language in offices, schools (although in practice often only in those founded by them and not by the state), courts and municipalities (if 20% of the deputies demanded it). From June 1907, all public and private schools in Hungary were obliged to ensure that after the fourth grade, the pupils could express themselves fluently in Hungarian. This led to the closing of several minority schools, devoted mostly to the Slovak and Rusyn languages.

The two kingdoms sometimes divided their spheres of influence. According to Misha Glenny in his book, The Balkans, 1804–1999, the Austrians responded to Hungarian support of Czechs by supporting the Croatian national movement in Zagreb.

In recognition that he reigned in a multi-ethnic country, Emperor Franz Joseph spoke (and used) German, Hungarian and Czech fluently, and Croatian, Serbian, Polish and Italian to some degree.

Jews

Around 1900, Jews numbered about two million in the whole territory of the Austro-Hungarian Empire;[72] their position was ambiguous. The populist and antisemitic politics of the Christian Social Party are sometimes viewed as a model for Adolf Hitler's Nazism.[73] Antisemitic parties and movements existed, but the governments of Vienna and Budapest did not initiate pogroms or implement official antisemitic policies. They feared that such ethnic violence could ignite other ethnic minorities and escalate out of control. The antisemitic parties remained on the periphery of the political sphere due to their low popularity among voters in the parliamentary elections.

In that period, the majority of Jews in Austria–Hungary lived in small towns (shtetls) in Galicia and rural areas in Hungary and Bohemia; however, they had large communities and even local majorities in the downtown districts of Vienna, Budapest and Prague. Of the pre-World War I military forces of the major European powers, the Austro-Hungarian army was almost alone in its regular promotion of Jews to positions of command.[74] While the Jewish population of the lands of the Dual Monarchy was about five percent, Jews made up nearly eighteen percent of the reserve officer corps.[75] Thanks to the modernity of the constitution and to the benevolence of emperor Franz Joseph, the Austrian Jews came to regard the era of Austria–Hungary as a golden era of their history.[76] By 1910 about 900,000 religious Jews made up approximately 5% of the population of Hungary and about 23% of Budapest's citizenry. Jews accounted for 54% of commercial business owners, 85% of financial institution directors and owners in banking, and 62% of all employees in commerce,[77] 20% of all general grammar school students, and 37% of all commercial scientific grammar school students, 31.9% of all engineering students, and 34.1% of all students in human faculties of the universities. Jews were accounted for 48.5% of all physicians,[78] and 49.4% of all lawyers/jurists in Hungary.[79] Note: The numbers of Jews were reconstructed from religious censuses. They did not include the people of Jewish origin who had converted to Christianity, or the number of atheists. Among many Hungarian parliament members of Jewish origin, the most famous Jewish members in Hungarian political life were Vilmos Vázsonyi as Minister of Justice, Samu Hazai as Minister of War, János Teleszky as minister of finance and János Harkányi as minister of trade, and József Szterényi as minister of trade.

Foreign policy

The minister of foreign affairs conducted the foreign relations of the Dual Monarchy, and negotiated treaties.[80]

The Dual Monarchy was created in the wake of a losing war in 1866 with Prussia and Italy. To rebuild Habsburg prestige and gain revenge against Prussia, Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust became foreign secretary. He hated Prussia's diplomat, Otto von Bismarck, who had repeatedly outmaneuvered him. Beust looked to France and negotiated with Emperor Napoleon III and Italy for an anti-Prussian alliance. No terms could be reached. The decisive victory of Prusso-German armies in the war of 1870 with France and the founding of the German Empire ended all hope of revenge and Beust retired.[81]

After being forced out of Germany and Italy, the Dual Monarchy turned to the Balkans, which were in tumult as nationalistic efforts were trying to end the rule of the Ottomans. Both Russia and Austria–Hungary saw an opportunity to expand in this region. Russia in particular took on the role of protector of Slavs and Orthodox Christians. Austria envisioned a multi-ethnic, religiously diverse empire under Vienna's control. Count Gyula Andrássy, a Hungarian who was Foreign Minister (1871 to 1879), made the centerpiece of his policy one of opposition to Russian expansion in the Balkans and blocking Serbian ambitions to dominate a new South Slav federation. He wanted Germany to ally with Austria, not Russia.[82]

When Russia defeated Turkey in a war the resulting Treaty of San Stefano was seen in Austria as much too favourable for Russia and its Orthodox-Slavic goals. The Congress of Berlin in 1878 let Austria occupy (but not annex) the province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a predominantly Slavic area. In 1914, Slavic militants in Bosnia rejected Austria's plan to fully absorb the area; they assassinated the Austrian heir and precipitated World War I.[83]

Voting rights

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Austrian half of the dual monarchy began to move towards constitutionalism. A constitutional system with a parliament, the Reichsrat was created, and a bill of rights was enacted also in 1867. Suffrage to the Reichstag's lower house was gradually expanded until 1907, when equal suffrage for all male citizens was introduced.

The 1907 Cisleithanian legislative election were the first elections held under universal male suffrage, after an electoral reform abolishing tax-paying requirements for voters had been adopted by the council and was endorsed by Emperor Franz Joseph earlier in the year.[84] However, seat allocations were based on tax revenues from the States.[84]

Demographics

The following data is based on the official Austro-Hungarian census conducted in 1910.

Population and area

| Area | Territory (km2) | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Empire of Austria | 300,005 (≈48% of Austria–Hungary) | 28,571,934 (≈57.8% of Austria–Hungary) |

| Kingdom of Hungary | 325,411 (≈52% of Austria–Hungary) | 20,886,487 (≈42.2% of Austria–Hungary) |

| Bosnia & Herzegovina | 51,027 | 1,931,802 |

| Sandžak (occupied until 1909) | 8,403 | 135,000 |

Languages

In Austria (Cisleithania), the census of 1910 recorded Umgangssprache, everyday language. Jews and those using German in offices often stated German as their Umgangssprache, even when having a different Muttersprache. 36.8% of the total population spoke German as their native language, and more than 71% of the inhabitants spoke some German.

In Hungary (Transleithania), the census was based primarily on mother tongue,[85][86] 48.1% of the total population spoke Hungarian as their native language. Not counting autonomous Croatia-Slavonia, more than 54.4% of the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Hungary were native speakers of Hungarian (this included also the Jews – around 5% of the population – as mostly they were Hungarian-speaking).[87][88]

Note that some languages were considered dialects of more widely spoken languages. For example: in the census, Rhaeto-Romance languages were counted as "Italian", while Istro-Romanian was counted as "Romanian". Yiddish was counted as "German" in both Austria and Hungary.

| Linguistic distribution of Austria–Hungary as a whole | |

|---|---|

| German | 23% |

| Hungarian | 20% |

| Czech | 13% |

| Polish | 10% |

| Ruthenian | 8% |

| Romanian | 6% |

| Croat | 6% |

| Slovak | 4% |

| Serbian | 4% |

| Slovene | 3% |

| Italian | 3% |

| Language | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| German | 12,006,521 | 23.36 |

| Hungarian | 10,056,315 | 19.57 |

| Czech | 6,442,133 | 12.54 |

| Serbo-Croatian | 5,621,797 | 10.94 |

| Polish | 4,976,804 | 9.68 |

| Ruthenian | 3,997,831 | 7.78 |

| Romanian | 3,224,147 | 6.27 |

| Slovak | 1,967,970 | 3.83 |

| Slovene | 1,255,620 | 2.44 |

| Italian | 768,422 | 1.50 |

| Other | 1,072,663 | 2.09 |

| Total | 51,390,223 | 100.00 |

.jpg.webp)

| Land | Most common language | Other languages (more than 2%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohemia | 63.2% | Czech | 36.45% (2,467,724) | German | ||||

| Dalmatia | 96.2% | Serbo-Croatian | 2.8% | Italian | ||||

| Galicia | 58.6% | Polish | 40.2% | Ruthenian | 1.1% | German | ||

| Lower Austria | 95.9% | German | 3.8% | Czech | ||||

| Upper Austria | 99.7% | German | 0.2% | Czech | ||||

| Bukovina | 38.4% | Ruthenian | 34.4% | Romanian | 21.2% | German | 4.6% | Polish |

| Carinthia | 78.6% | German | 21.2% | Slovene | ||||

| Carniola | 94.4% | Slovene | 5.4% | German | ||||

| Salzburg | 99.7% | German | 0.1% | Czech | ||||

| Silesia | 43.9% | German | 31.7% | Polish | 24.3% | Czech | ||

| Styria | 70.5% | German | 29.4% | Slovene | ||||

| Moravia | 71.8% | Czech | 27.6% | German | 0.6% | Polish | ||

| Gorizia and Gradisca | 59.3% | Slovene | 34.5% | Italian | 1.7% | German | ||

| Trieste | 51.9% | Italian | 24.8% | Slovene | 5.2% | German | 1.0% | Serbo-Croatian |

| Istria | 41.6% | Serbo-Croatian | 36.5% | Italian | 13.7% | Slovene | 3.3% | German |

| Tyrol | 57.3% | German | 38.9% | Italian | ||||

| Vorarlberg | 95.4% | German | 4.4% | Italian | ||||

| Language | Hungary proper | Croatia-Slavonia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| speakers | % of population | speakers | % of population | |

| Hungarian | 9,944,627 | 54.5% | 105,948 | 4.1% |

| Romanian | 2,948,186 | 16.0% | 846 | <0.1% |

| Slovak | 1,946,357 | 10.7% | 21,613 | 0.8% |

| German | 1,903,657 | 10.4% | 134, 078 | 5.1% |

| Serbian | 461,516 | 2.5% | 644,955 | 24.6% |

| Ruthenian | 464,270 | 2.3% | 8,317 | 0.3% |

| Croatian | 194,808 | 1.1% | 1,638,354 | 62.5% |

| Others and unspecified | 401,412 | 2.2% | 65,843 | 2.6% |

| Total | 18,264,533 | 100% | 2,621,954 | 100% |

Historical regions:

| Region | Mother tongues | Hungarian language | Other languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transylvania | Romanian – 2,819,467 (54%) | 1,658,045 (31.7%) | German – 550,964 (10.5%) |

| Upper Hungary | Slovak – 1,688,413 (55.6%) | 881,320 (32.3%) | German – 198,405 (6.8%) |

| Délvidék | Serbo-Croatian – 601,770 (39.8%) | 425,672 (28.1%) | German – 324,017 (21.4%) Romanian – 75,318 (5.0%) Slovak – 56,690 (3.7%) |

| Transcarpathia | Ruthenian – 330,010 (54.5%) | 185,433 (30.6%) | German – 64,257 (10.6%) |

| Fiume | Italian – 24,212 (48.6%) | 6,493 (13%) |

|

| Őrvidék | German – 217,072 (74.4%) | 26,225 (9%) | Croatian – 43,633 (15%) |

| Prekmurje | Slovene – 74,199 (80.4%) – in 1921 | 14,065 (15.2%) – in 1921 | German – 2,540 (2.8%) – in 1921 |

Religion

| Religion | Austria–Hungary | Austria/Cisleithania |

Hungary/Transleithania |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholics (both Roman and Eastern) | 76.6% | 90.9% | 61.8% | 22.9% |

| Protestants | 8.9% | 2.1% | 19.0% | 0% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 8.7% | 2.3% | 14.3% | 43.5% |

| Jews | 4.4% | 4.7% | 4.9% | 0.6% |

| Muslims | 1.3% | 0% | 0% | 32.7% |

Solely in the Empire of Austria:[89]

| Religion | Austria |

|---|---|

| Latin Catholic | 79.1% (20,661,000) |

| Eastern Catholic | 12% (3,134,000) |

| Jewish | 4.7% (1,225,000) |

| Eastern Orthodox | 2.3% (607,000) |

| Lutheran | 1.9% (491,000) |

| Other or no religion | 14,000 |

Solely in the Kingdom of Hungary:[90]

| Religion | Hungary proper & Fiume | Croatia & Slavonia |

|---|---|---|

| Latin Catholic | 49.3% (9,010,305) | 71.6% (1,877,833) |

| Calvinist | 14.3% (2,603,381) | 0.7% (17,948) |

| Eastern Orthodox | 12.8% (2,333,979) | 24.9% (653,184) |

| Eastern Catholic | 11.0% (2,007,916) | 0.7% (17,592) |

| Lutheran | 7.1% (1,306,384) | 1.3% (33,759) |

| Jewish | 5.0% (911,227) | 0.8% (21,231) |

| Unitarian | 0.4% (74,275) | 0.0% (21) |

| Other or no religion | 0.1% (17,066) | 0.0 (386) |

Largest cities

| Rank | Current English name | Contemporary official name[92] | Other | Present-day country | Population in 1910 | Present-day population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Vienna | Wien | Bécs, Beč, Dunaj | Austria | 2,031,498 (city without the suburb 1,481,970) | 1,840,573 (Metro: 2,600,000) |

| 2. | Prague | Prag, Praha | Prága | Czech Republic | 668,000 (city without the suburb 223,741) | 1,301,132 (Metro: 2,620,000) |

| 3. | Trieste | Triest | Trieszt, Trst | Italy | 229,510 | 204,420 |

| 4. | Lviv | Lemberg, Lwów | Ilyvó, Львів, Lvov, Львов | Ukraine | 206,113 | 728,545 |

| 5. | Kraków | Krakau, Kraków | Krakkó, Krakov | Poland | 151,886 | 762,508 |

| 6. | Graz | Grác, Gradec | Austria | 151,781 | 328,276 | |

| 7. | Brno | Brünn, Brno | Berén, Börön, Börénvásár | Czech Republic | 125,737 | 377,028 |

| 8. | Chernivtsi | Czernowitz | Csernyivci, Cernăuți, Чернівці | Ukraine | 87,128 | 242,300 |

| 9. | Plzeň | Pilsen, Plzeň | Pilzen | Czech Republic | 80,343 | 169,858 |

| 10. | Linz | Linec | Austria | 67,817 | 200,841 |

| Rank | Current English name | Contemporary official name[92] | Other | Present-day country | Population in 1910 | Present-day population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Budapest | Budimpešta | Hungary | 1,232,026 (city without the suburb 880,371) | 1,735,711 (Metro: 3,303,786) | |

| 2. | Szeged | Szegedin, Segedin | Hungary | 118,328 | 170,285 | |

| 3. | Subotica | Szabadka | Суботица | Serbia | 94,610 | 105,681 |

| 4. | Debrecen | Hungary | 92,729 | 208,016 | ||

| 5. | Zagreb | Zágráb, Agram | Croatia | 79,038 | 803,000 (Metro: 1,228,941) | |

| 6. | Bratislava | Pozsony | Pressburg, Prešporok | Slovakia | 78,223 | 425,167 |

| 7. | Timișoara | Temesvár | Temeswar | Romania | 72,555 | 319,279 |

| 8. | Kecskemét | Hungary | 66,834 | 111,411 | ||

| 9. | Oradea | Nagyvárad | Großwardein | Romania | 64,169 | 196,367 |

| 10. | Arad | Arad | Romania | 63,166 | 159,074 | |

| 11. | Hódmezővásárhely | Hungary | 62,445 | 46,047 | ||

| 12. | Cluj-Napoca | Kolozsvár | Klausenburg | Romania | 60,808 | 324,576 |

| 13. | Újpest | Hungary | 55,197 | 100,694 | ||

| 14. | Miskolc | Hungary | 51,459 | 157,177 | ||

| 15. | Pécs | Hungary | 49,852 | 145,347 | ||

Austrian Empire

Primary and secondary schools

The organization of the Austrian elementary schools was based on the principle of compulsory school attendance, free education, and the imparting of public instruction in the child's own language. Side by side with these existed private schools. The proportion of children attending private schools to those attending the public elementary schools in 1912 was 144,000 to 4.5 millions, i.e. a thirtieth part. Hence the accusation of denationalizing children through the Schulvereine must be accepted with caution. The expenses of education were distributed as follows: the communes built the schoolhouses, the political sub-districts (Bezirke) paid the teachers, the Crown territory gave a grant, and the State appointed the inspectors. Since the State supervised the schools without maintaining them, it was able to increase its demands without being hampered by financial considerations. It is remarkable that the difference between the State educational estimates in Austria and in Hungary was one of 9.3 millions in the former as opposed to 67.6 in the latter. Under Austria, since everywhere that 40 scholars of one nationality were to be found within a radius of 5 km. a school had to be set up in which their language was used, national schools were assured even to linguistic minorities. It is true that this mostly happened at the expense of the German industrial communities, since the Slav labourers as immigrants acquired schools in their own language. The number of elementary schools increased from 19,016 in 1900 to 24,713 in 1913; the number of scholars from 3,490,000 in 1900 to 4,630,000 in 1913.[93]

Universities in Austrian Empire

The first University in the Austrian half of the Empire (Charles University) was founded by H.R. Emperor Charles IV in Prague in 1347. The second oldest university (University of Vienna) was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365.[94]

The higher educational institutions were predominantly German, but beginning in the 1870s, language shifts began to occur.[95] These establishments, which in the middle of the 19th century had had a predominantly German character, underwent in Galicia a conversion into Polish national institutions, in Bohemia and Moravia a separation into German and Czech ones. Thus Germans, Czechs and Poles were provided for. But now the smaller nations also made their voices heard: the Ruthenians, Slovenes and Italians. The Ruthenians demanded at first, in view of the predominantly Ruthenian character of East Galicia, a national partition of the Polish university existing there. Since the Poles were at first unyielding, Ruthenian demonstrations and strikes of students arose, and the Ruthenians were no longer content with the reversion of a few separate professorial chairs, and with parallel courses of lectures. By a pact concluded on 28 January 1914 the Poles promised a Ruthenian university; but owing to the war the question lapsed. The Italians could hardly claim a university of their own on grounds of population (in 1910 they numbered 783,000), but they claimed it all the more on grounds of their ancient culture. All parties were agreed that an Italian faculty of laws should be created; the difficulty lay in the choice of the place. The Italians demanded Trieste; but the Government was afraid to let this Adriatic port become the centre of an irredenta; moreover the Southern Slavs of the city wished it kept free from an Italian educational establishment. Bienerth in 1910 brought about a compromise; namely, that it should be founded at once, the situation to be provisionally in Vienna, and to be transferred within four years to Italian national territory. The German National Union (Nationalverband) agreed to extend temporary hospitality to the Italian university in Vienna, but the Southern Slav Hochschule Club demanded a guarantee that a later transfer to the coast provinces should not be contemplated, together with the simultaneous foundation of Slovene professorial chairs in Prague and Cracow, and preliminary steps towards the foundation of a Southern Slav university in Laibach. But in spite of the constant renewal of negotiations for a compromise it was impossible to arrive at any agreement, until the outbreak of war left all the projects for a Ruthenian university at Lemberg, a Slovene one in Laibach, and a second Czech one in Moravia, unrealized.

Kingdom of Hungary

Primary and secondary schools

One of the first measures of newly established Hungarian government was to provide supplementary schools of a non-denominational character. By a law passed in 1868 attendance at school was obligatory for all children between the ages of 6 and 12 years. The communes or parishes were bound to maintain elementary schools, and they were entitled to levy an additional tax of 5% on the state taxes for their maintenance. But the number of state-aided elementary schools was continually increasing, as the spread of the Magyar language to the other races through the medium of the elementary schools was one of the principal concerns of the Hungarian government, and was vigorously pursued. In 1902 there were in Hungary 18,729 elementary schools with 32,020 teachers, attended by 2,573,377 pupils, figures which compare favourably with those of 1877, when there were 15,486 schools with 20,717 teachers, attended by 1,559,636 pupils. In about 61% of these schools the language used was exclusively Magyar, in about 6 20% it was mixed, and in the remainder some non-Magyar language was used. In 1902, 80.56% of the children of school age actually attended school. Since 1891 infant schools, for children between the ages of 3 and 6 years, were maintained either by the communes or by the state.

The public instruction of Hungary contained three other groups of educational institutions: middle or secondary schools, "high schools" and technical schools. The middle schools comprised classical schools (gymnasia) which were preparatory for the universities and other "high schools", and modern schools (Realschulen) preparatory for the technical schools. Their course of study was generally eight years, and they were maintained mostly by the state. The state-maintained gymnasia were mostly of recent foundation, but some schools maintained by the various churches had been in existence for three or sometimes four centuries. The number of middle schools in 1902 was 243 with 4705 teachers, attended by 71,788 pupils; in 1880 their number was 185, attended by 40,747 pupils.

Universities in Kingdom of Hungary

In the year 1276, the university of Veszprém was destroyed by the troops of Péter Csák and it was never rebuilt. A university was established by Louis I of Hungary in Pécs in 1367. Sigismund established a university at Óbuda in 1395. Another, Universitas Istropolitana, was established 1465 in Pozsony (now Bratislava in Slovakia) by Mattias Corvinus. None of these medieval universities survived the Ottoman wars. Nagyszombat University was founded in 1635 and moved to Buda in 1777 and it is called Eötvös Loránd University today. The world's first institute of technology was founded in Selmecbánya, Kingdom of Hungary (since 1920 Banská Štiavnica, now Slovakia) in 1735. Its legal successor is the University of Miskolc in Hungary. The Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) is considered the oldest institute of technology in the world with university rank and structure. Its legal predecessor the Institutum Geometrico-Hydrotechnicum was founded in 1782 by Emperor Joseph II.

The high schools included the universities, of which Hungary possessed five, all maintained by the state: at Budapest (founded in 1635), at Kolozsvár (founded in 1872), and at Zagreb (founded in 1874). Newer universities were established in Debrecen in 1912, and Pozsony university was reestablished after a half millennium in 1912. They had four faculties: theology, law, philosophy and medicine (the university at Zagreb was without a faculty of medicine). There were in addition ten high schools of law, called academies, which in 1900 were attended by 1569 pupils. The Polytechnicum in Budapest, founded in 1844, which contained four faculties and was attended in 1900 by 1772 pupils, was also considered a high school. There were in Hungary in 1900 forty-nine theological colleges, twenty-nine Catholic, five Greek Uniat, four Greek Orthodox, ten Protestant and one Jewish. Among special schools the principal mining schools were at Selmeczbánya, Nagyág and Felsőbánya; the principal agricultural colleges at Debreczen and Kolozsvár; and there was a school of forestry at Selmeczbánya, military colleges at Budapest, Kassa, Déva and Zagreb, and a naval school at Fiume. There were in addition a number of training institutes for teachers and a large number of schools of commerce, several art schools – for design, painting, sculpture, music.

| Major nationalities in Hungary | Rate of literacy in 1910 |

|---|---|

| German | 70.7% |

| Hungarian | 67.1% |

| Croatian | 62.5% |

| Slovak | 58.1% |

| Serbian | 51.3% |

| Romanian | 28.2% |

| Ruthenian | 22.2% |

Economy

The Austro-Hungarian economy changed dramatically during the Dual Monarchy. The capitalist way of production spread throughout the Empire during its 50-year existence. Technological change accelerated industrialization and urbanization. The first Austrian stock exchange (the Wiener Börse) was opened in 1771 in Vienna, the first stock exchange of the Kingdom of Hungary (the Budapest Stock Exchange) was opened in Budapest in 1864. The central bank (Bank of issue) was founded as Austrian National Bank in 1816. In 1878, it transformed into Austro-Hungarian National Bank with principal offices in both Vienna and Budapest.[97] The central bank was governed by alternating Austrian or Hungarian governors and vice-governors.[98]

The gross national product per capita grew roughly 1.76% per year from 1870 to 1913. That level of growth compared very favorably to that of other European nations such as Britain (1%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%).[99] However, in a comparison with Germany and Britain, the Austro-Hungarian economy as a whole still lagged considerably, as sustained modernization had begun much later. Like the German Empire, that of Austria–Hungary frequently employed liberal economic policies and practices. In 1873, the old Hungarian capital Buda and Óbuda (Ancient Buda) were officially merged with the third city, Pest, thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. The dynamic Pest grew into Hungary's administrative, political, economic, trade and cultural hub. Many of the state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period. Economic growth centered on Vienna and Budapest, the Austrian lands (areas of modern Austria), the Alpine region and the Bohemian lands. In the later years of the 19th century, rapid economic growth spread to the central Hungarian plain and to the Carpathian lands. As a result, wide disparities of development existed within the empire. In general, the western areas became more developed than the eastern ones. The Kingdom of Hungary became the world's second-largest flour exporter after the United States.[100] The large Hungarian food exports were not limited to neighbouring Germany and Italy: Hungary became the most important foreign food supplier of the large cities and industrial centres of the United Kingdom.[101] Galicia, which has been described as the poorest province of Austro-Hungary, experienced near-constant famines, resulting in 50,000 deaths a year.[102] The Istro-Romanians of Istria were also poor, as pastoralism lost strength and agriculture was not productive.[69]

However, by the end of the 19th century, economic differences gradually began to even out as economic growth in the eastern parts of the monarchy consistently surpassed that in the western. The strong agriculture and food industry of the Kingdom of Hungary with the centre of Budapest became predominant within the empire and made up a large proportion of the export to the rest of Europe. Meanwhile, western areas, concentrated mainly around Prague and Vienna, excelled in various manufacturing industries. This division of labour between the east and west, besides the existing economic and monetary union, led to an even more rapid economic growth throughout Austria–Hungary by the early 20th century. However, since the turn of the twentieth century, the Austrian half of the Monarchy could preserve its dominance within the empire in the sectors of the first industrial revolution, but Hungary had a better position in the industries of the second industrial revolution, in these modern sectors of the second industrial revolution the Austrian competition could not become dominant.[103]

The empire's heavy industry had mostly focused on machine building, especially for the electric power industry, locomotive industry and automotive industry, while in light industry the precision mechanics industry was the most dominant. Through the years leading up to World War I the country became the 4th biggest machine manufacturer in the world.[104]

The two most important trading partners were traditionally Germany (1910: 48% of all exports, 39% of all imports), and Great Britain (1910: almost 10% of all exports, 8% of all imports), the third most important partner was the United States, it followed by Russia, France, Switzerland, Romania, the Balkan states and South America.[8] Trade with the geographically neighbouring Russia, however, had a relatively low weight (1910: 3% of all exports /mainly machinery for Russia, 7% of all imports /mainly raw materials from Russia).

Automotive industry

Prior to World War I, the Austrian Empire had five car manufacturer companies. These were: Austro-Daimler in Wiener-Neustadt (cars trucks, buses),[105] Gräf & Stift in Vienna (cars),[106] Laurin & Klement in Mladá Boleslav (motorcycles, cars),[107] Nesselsdorfer in Nesselsdorf (Kopřivnice), Moravia (automobiles), and Lohner-Werke in Vienna (cars).[108] Austrian car production started in 1897.

Prior to World War I, the Kingdom of Hungary had four car manufacturer companies. These were: the Ganz company[109][110] in Budapest, RÁBA Automobile[111] in Győr, MÁG (later Magomobil)[112][113] in Budapest, and MARTA (Hungarian Automobile Joint-stock Company Arad)[114] in Arad. Hungarian car production started in 1900. Automotive factories in the Kingdom of Hungary manufactured motorcycles, cars, taxicabs, trucks and buses.

Electrical industry and electronics

In 1884, Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy and Miksa Déri (ZBD), three engineers associated with the Ganz Works of Budapest, determined that open-core devices were impractical, as they were incapable of reliably regulating voltage.[115] When employed in parallel connected electric distribution systems, closed-core transformers finally made it technically and economically feasible to provide electric power for lighting in homes, businesses and public spaces.[116][117] The other essential milestone was the introduction of 'voltage source, voltage intensive' (VSVI) systems'[118] by the invention of constant voltage generators in 1885.[119] Bláthy had suggested the use of closed cores, Zipernowsky had suggested the use of parallel shunt connections, and Déri had performed the experiments;[120]

The first Hungarian water turbine was designed by the engineers of the Ganz Works in 1866, the mass production with dynamo generators started in 1883.[121] The manufacturing of steam turbo generators started in the Ganz Works in 1903.

In 1905, the Láng Machine Factory company also started the production of steam turbines for alternators.[122]

Tungsram is a Hungarian manufacturer of light bulbs and vacuum tubes since 1896. On 13 December 1904, Hungarian Sándor Just and Croatian Franjo Hanaman were granted a Hungarian patent (No. 34541) for the world's first tungsten filament lamp. The tungsten filament lasted longer and gave brighter light than the traditional carbon filament. Tungsten filament lamps were first marketed by the Hungarian company Tungsram in 1904. This type is often called Tungsram-bulbs in many European countries.[123]

Despite the long experimentation with vacuum tubes at Tungsram company, the mass production of radio tubes begun during WW1,[124] and the production of X-ray tubes started also during the WW1 in Tungsram Company.[125]

The Orion Electronics was founded in 1913. Its main profiles were the production of electrical switches, sockets, wires, incandescent lamps, electric fans, electric kettles, and various household electronics.

The telephone exchange was an idea of the Hungarian engineer Tivadar Puskás (1844–1893) in 1876, while he was working for Thomas Edison on a telegraph exchange.[126][127][128][129][130]

The first Hungarian telephone factory (Factory for Telephone Apparatuses) was founded by János Neuhold in Budapest in 1879, which produced telephones microphones, telegraphs, and telephone exchanges.[131][132][133]

In 1884, the Tungsram company also started to produce microphones, telephone apparatuses, telephone switchboards and cables.[134]

The Ericsson company also established a factory for telephones and switchboards in Budapest in 1911.[135]

Aeronautic industry

The first airplane in Austria was Edvard Rusjan's design, the Eda I, which had its maiden flight in the vicinity of Gorizia on 25 November 1909.[136]

The first Hungarian hydrogen-filled experimental balloons were built by István Szabik and József Domin in 1784. The first Hungarian designed and produced airplane (powered by a Hungarian built inline engine) was flown at Rákosmező on 4 November[137] 1909.[138] The earliest Hungarian airplane with Hungarian built radial engine was flown in 1913. Between 1912 and 1918, the Hungarian aircraft industry began developing. The three greatest: UFAG Hungarian Aircraft Factory (1914), Hungarian General Aircraft Factory (1916), Hungarian Lloyd Aircraft, Engine Factory at Aszód (1916),[139] and Marta in Arad (1914).[140] During the First World War, fighter planes, bombers and reconnaissance planes were produced in these factories. The most important aero-engine factories were Weiss Manfred Works, GANZ Works, and Hungarian Automobile Joint-stock Company Arad.

Locomotive engine and railway vehicle manufacturers

The locomotive (steam engines and wagons, bridge and iron structures) factories were installed in Vienna (Locomotive Factory of the State Railway Company, founded in 1839), in Wiener Neustadt (New Vienna Locomotive Factory, founded in 1841), and in Floridsdorf (Floridsdorf Locomotive Factory, founded in 1869).[141][142][143]

The Hungarian Locomotive (engines and wagons bridge and iron structures) factories were the MÁVAG company in Budapest (steam engines and wagons) and the Ganz company in Budapest (steam engines, wagons, the production of electric locomotives and electric trams started from 1894).[144] and the RÁBA Company in Győr.

Infrastructure

Telegraph

The first telegraph connection (Vienna – Brno – Prague) had started operation in 1847.[145] In Hungarian territory the first telegraph stations were opened in Pressburg (Pozsony, today's Bratislava) in December 1847 and in Buda in 1848. The first telegraph connection between Vienna and Pest–Buda (later Budapest) was constructed in 1850,[146] and Vienna–Zagreb in 1850.[147]

Austria subsequently joined a telegraph union with German states.[148] In the Kingdom of Hungary, 2,406 telegraph post offices operated in 1884.[149] By 1914 the number of telegraph offices reached 3,000 in post offices and further 2,400 were installed in the railway stations of the Kingdom of Hungary.[150]

Telephone