Battle of Halen

The Battle of Halen, also known as the Battle of the Silver Helmets (Dutch: Slag der Zilveren Helmen, French: Bataille des casques d'argent) because of the many cavalry helmets left behind on the battlefield by the German cuirassiers, took place on 12 August 1914 at the beginning of the First World War, between German forces led by Georg von der Marwitz and Belgian troops led by Léon De Witte. The name of the battle alludes to the Battle of the Golden Spurs (11 July 1302), when 500 pairs of golden spurs were recovered from the battlefield. Halen (Haelen in French) was a small market town and a convenient river crossing of the Gete and was situated on the principal axis of advance of the Imperial German army.[lower-alpha 1] The battle was a Belgian tactical victory but did little to delay the German invasion of Belgium.

| Battle of Halen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Frontiers in the First World War | |||||||

Contemporary postcard depicting the failure of the German cavalry at Halen | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5 regiments 2,400 cavalry 450 infantry cyclists |

6 regiments 4,000 cavalry 2,000 infantry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

160 killed 320 wounded |

150 killed 600 wounded 300 captured | ||||||

Halen Halen (Haelen), a market town in the province of Limburg in eastern Belgium | |||||||

Background

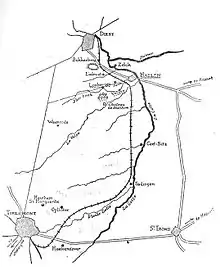

On 3 August the Belgian government refused a German ultimatum and the British government guaranteed military support to Belgium if Germany invaded. Germany declared war on France, the British government ordered general mobilisation and Italy declared neutrality. On 4 August, the British government sent an ultimatum to Germany and declared war on Germany at midnight on 4/5 August, Central European time. Belgium severed diplomatic relations with Germany and Germany declared war on Belgium. German troops crossed the Belgian frontier and attacked Liège.[1] A week after the German invasion, German cavalry had been operating towards Hasselt and Diest, which threatened the left flank of the army on the Gete. Belgian general headquarters chose Halen as a place to delay the advance and make time to complete an orderly retreat to the west. The Belgian Cavalry Division was sent from Sint-Truiden to Büdingen and Halen, to extend the Belgian left flank.[2]

Prelude

The German II Cavalry Corps (Höhere Kavallerie-Kommando2 [HKK 2]) commanded by General Georg von der Marwitz, was ordered to conduct reconnaissances towards Antwerp, Brussels and Charleroi. By 7 August, the scouting parties had found that the area to a line from Diest to Huy was empty of Belgian and Allied troops. Belgian and French troops were rumoured to be between Tienen and Huy; Marwitz advanced to the north, towards parties of Belgian cavalry, which had retired towards Diest.[3] On 11 August, large bodies of German cavalry, artillery and infantry had been seen by Belgian cavalry scouts in the area from Sint-Truiden to Hasselt and Diest. Belgian headquarters anticipated that the German manoeuvres foreshadowed a German advance towards Hasselt and Diest. To block the German advance, the Belgian Cavalry Division commanded by Lieutenant-General Léon de Witte was sent to guard the bridge over the River Gete at Halen. During an evening meeting, the Belgian general staff convinced de Witte to fight a dismounted action, to negate the German numerical advantage.[4]

General de Witte had garrisoned the Gete crossings at Diest, Halen, Geetbets and Budingen. The main road from Hasselt to Diest passed through this village, most of which was on the left bank. If captured, Loksbergen and Waanrode would be outflanked and the left wing of the Belgian army threatened. General de Witte used Halen as an outpost and concentrated a battalion of cyclist infantry and dismounted cavalry behind the village, from Zelk to Velpen and the hamlet of Liebroek, to act as a line of resistance if Halen were captured.[5] At Halen, there are a number of bridges across the rivers Gete and Velp. The village is also transected by the Grootebaan (the main road), which connects Hasselt and Diest. At the start of the war, there were not many bridges in the region, making those at Halen tactically important. The Belgian, as well as the German military high commands, was fully aware of this. Equally important, to the south of the Halen town centre, ran an elevated railway dam which followed a wide, south to north curve through the landscape. This was the former train connexion between the towns of Tienen and Diest, nowadays still prominent in the landscape, partly coinciding with Sportlaan and Stadsbeemd streets and further used as a tourist cycle track. Of the old Halen train station, nothing is left.[6]

To defeat France, the German deployment plan based on work by Alfred von Schlieffen and Helmuth von Moltke included a rapid push through Belgium to avoid the French fortifications along the border with Germany. The rapid capture of Liège, a big railway junction, was crucial for the Germans. Although the city fell on 7 August, the surrounding forts held out until 16 August. Due to the resistance around Liège, East-Brabant and the Gete River drew the attention of the Germans. If their army could push through somewhere between the towns of Diest and Sint-Truiden, the road to Brussels would lay open, driving a wedge between the Belgian army divisions to the north and to the south.[7]

Battle

11 August

Since the outbreak of the war, General De Witte had been assigned reconnaissance tasks in the provinces of Liège and Limburg and his cavalry division was also responsible for the defence of the long and vulnerable east flank of the Belgian army. On 11 August, there was an exchange of fire between groups of scouts near the river Halbeek at Herk-de-Stad and at the bridge across the Gete at Halen. It became clear, while the battle for the fortifications around Liège was still going on, that the cavalry corps from General Georg von der Marwitz would be deployed near Halen to cross the river Gete and push through in the direction of Brussels as quickly as possible. Marwitz's diary proves that it was indeed the intention to reach Brussels. Two days after his defeat at Halen he wrote,

They shall be very unhappy about my service, this I knew beforehand. Everyone had thought that we should have ridden on to Brussels. But it was an impossibility in these terrible circumstances![8]

On the night of 11/12 August, De Witte and his staff decided that, on the following day, lancers and scouts would fight dismounted with their carbines. This deviation from the old battle traditions was the inspiration of two young officers, Commander Tasnier and Lieutenant Van Overstraeten.

12 August: morning

It was only in the early hours of the 12 August that the Belgian army command at Leuven realised that the Germans were directing large amounts of infantry and cavalry to Halen. The German cavalry did not begin to move until 12 August due to the fatigue of the horses caused by the intense summer heat and a lack of oats. The 2nd Cavalry Division (Major-General von Krane) advanced through Hasselt to Spalbeek and the 4th Cavalry Division (Lieutenant-General Otto von Garnier) advanced via Alken to Stevoort. At 7:00 a.m., the Belgian Headquarters discovered from intercepted wireless messages that German troops were advancing towards de Witte's position and sent the 4th Mixed Brigade to reinforce the Cavalry Division. The reinforcements took until 2:00 and 3:00 p.m. to arrive.[9]

The majority of the Belgian troops had taken position near and to the south of the IJzerwinningshoeve (a local farmhouse). Only one company of carabineer-cyclists (approximately 150 men) guarded the bridge across the Gete. Marwitz ordered the 4th Cavalry Division to cross the Gete and at 8:45 a.m., the 7th and 9th Jäger battalions advanced.[9] Around 8:00 a.m., German infantry, backed by artillery, attacked the bridge and soon made the defenders' position untenable. The decision was made to blow up the bridge and to retreat to the south of Halen behind the railway dam. Due to the poor quality of the Belgian gunpowder, the explosion only partly destroyed the bridge. A German scouting party advancing from Herk-de-Stad came under fire from Belgian troops and c. 200 Belgian troopers attempted to set up a fortified position in the old brewery in Halen but were driven out when the Germans brought up field artillery and got c. 1,000 troops into the centre of Halen.[4]

The German command was euphoric when informed that the important bridge had been taken quickly and almost undamaged. German cavalry units moved into Halen in force. At the same time, a pontoon bridge was built near Landwijk castle at Donk to transfer more troops across the Gete for a flank attack on the Belgians. The first attacks on the station of Halen and the railway dam were repulsed by two companies of carabineer-cyclists with rifle and machine-gun fire. The pressure of the German infantry attacks made their position untenable; around noon the soldiers retreated on foot through fields, to join the main force of the division. The Belgian artillery opened fire, which exposed its masked positions; the artillery officers had had ample time to explore the landscape and take up their positions and the guns on the hill known as the Mettenberg were sited perfectly. The shells exploded in the centre of Halen, where a large number of German troops were positioned and caused panic. At first, the Germans thought the artillery-fire was coming from a hill known as the Bokkenberg.[10]

12 August: afternoon

Shortly after noon, two squadrons of the 17th Dragoon Regiment advanced along the Diestersteenweg to the foot of the Bokkenberg. In Zelk, they were engaged by troops behind a barricade. The road was lined with hedges and had been fenced off with barbed wire, forcing the dragoons to make a frontal attack; a great number of them were killed, wounded or captured. The Belgian guns continued firing, followed almost immediately by a new charge by the dragoons across the railway dam, towards the Mettenberg. The Belgian carabineer-cyclists were still retreating through the fields and had already crossed the Betserbaan, a sunken north–south road. Overstraeten feared they were retreating too fast and ordered the carabineer-cyclists to return to the sunken road and take up new positions there but the German cavalry were already advancing through the fields. Over the next two hours, regiments of dragoons, cuirassiers and uhlans appeared on the battlefield in the same order as they had crossed the Gete river and charged with lance and sabre.[10]

The carabineer-cyclists were caught in the open between the Betserbaan (road) and IJzerwinning farm. The sunken road in front of them was a barrier for the charging cavalry and the accuracy of the Belgian artillery dispersed the German cavalry. The sheer volume of the German attacks overpowered the carabineer-cyclists and captains Van Damme and Panquin were killed. Once their position had been overrun, they were caught in cross-fire, when the Belgian lancers in IJzerwinning farm opened fire. The numerous charges by the German cavalry were eventually stopped by small-arms fire. The German attacks on the Belgian guns on the Mettenberg were failures and they were unable immediately to advance to IJzerwinning farm. Backed by their artillery near Halen station and in the village of Velpen, the German infantry attacked the farm and eventually overwhelmed the defenders. With much delay this bad news reached the Belgian headquarters at Leuven,

The cavalry is retreating on Kersbeek-Miscom (...) there is almost nothing left of the entire division.

The breakthrough on the eastern flank of the Belgian army now seemed a fact and King Albert was advised to leave Leuven immediately.[10]

12 August: evening

Belgian troops were steadily losing ground and the situation seemed hopeless. Between 2:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m., the first soldiers of the Mixed Brigade appeared on the battlefield, after a 17 km (11 mi) march from Tienen. Their artillery was put in position on the Molenberg ("Windmill Hill") and in the centre of the village of Loksbergen. Brigade machine-gun sections immediately opened fire on the Germans. Support also came from the nearby town of Diest. Around 5:00 p.m., Colonel Dujardin assembled a combat unit that drove from Diest to Zelk in six cars. Colonel Dujardin was severely wounded at Zelk but Lieutenant van Dooren, of the 4th Regiment of Mounted Chasseurs, succeeded with a few men in silencing the German artillery along the road to Halen. Around 7:00 p.m., IJzerwinning farm was recaptured and De Witte then ordered a counterattack on Velpen and Halen to push the enemy back to the right bank of the river Gete. Unlike the cavalry division, the 4th Mixed Brigade was mainly composed of conscripts and lacked officers. The inexperienced infantry blindly attacked towards the village of Velp, where German machine-gunners had taken cover in a number of houses and farms, and were repulsed. There was a lull at dusk when, impressed by the Belgian resistance and after limited territorial gain and the arrival of Belgian reinforcements, the Germans broke off their attack and retreated. At 11:00 p.m. a telegram from General De Witte reached King Albert's headquarters at Leuven:

... The German troops were repelled on Halen with enormous losses in men and horses...[11]

Aftermath

Analysis

De Witte had repulsed the German cavalry attacks by ordering the cavalry, which included a company of cyclists and one of pioneers, to fight dismounted and meet the attack with massed rifle fire. Significant casualties were inflicted upon the Germans. The German cavalry had managed to obscure the operations on the German right flank, established a front parallel with Liège and discovered the positions of the Belgian field army but had not been able to penetrate beyond the Belgian front line and reconnoitre Belgian dispositions beyond.[12][13] Maximilian von Poseck said after the battle,

The brigade is destroyed.... Rode in against infantry, artillery and machine-guns, hung up on the wire, fell into a sunken road, all shot down.

— Maximilian von Poseck[14]

Although a Belgian victory, the battle had little effect and the Germans later besieged and captured the fortified areas of Namur, Liège and Antwerp, on which Belgian strategy was based. The German advance was stopped at the Battle of the Yser at the end of October 1914, by which time the Germans had driven Belgian and Allied troops out of most of Belgium and imposed a military government.[15]

The fact of the Belgian cavalry fighting dismounted and in that way overcoming the still mounted German cavalry was an early indication of the fact that cavalry - for many centuries a major component of all armies - had become obsolete. With later development of the war and its transformation into trench warfare, all contending armies became aware of this momentous change.

Casualties

The German 4th Cavalry Division suffered casualties of 501 men and c. 848 horses during the battle, casualty rates of 16 per cent and 28 per cent.[14] Casualties of the 2nd and 4th Cavalry divisions were 150 dead, 600 wounded and 200–300 prisoners.[16] The Belgian army suffered 1,122 casualties, including 160 dead and 320 wounded.[17]

Subsequent operations

Until the German advance into France began, the 2nd Cavalry Division remained near Hasselt to guard the area near the Gete and the 4th Cavalry Division moved south on 13 August to the area around Loon, then moved towards the south-east of Tienen and joined the 9th Cavalry Division, which had crossed the Meuse on 14 August. On 16 August, Marwitz advanced with the two divisions to Opprebais and Chaumont-Gistoux, where skirmishing with cavalry and artillery occurred, before meeting infantry who were well dug-in. Next day the cavalry slowly retired towards Hannut.[18]

44 helmets

For the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War, 44 helmets in concrete were constructed and placed in the town Halen near the battlefield to symbolise the German occupation of the area during the war. Each helmet represents one of the towns in Limburg.[19][20][21]

Notes

Footnotes

- Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 6.

- Essen 1917, pp. 106–107.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 107–108.

- General Staff 1915, p. 19.

- Essen 1917, p. 107.

- Hove 2014, p. 2.

- Hove 2014, p. 4.

- Hove 2014, p. 5.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 108.

- Hove 2014, p. 6.

- Hove 2014, p. 7–8.

- General Staff 1915, pp. 20–21.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 109.

- Brose 2001, p. 190.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 208–224, 262–281.

- Duffy 2009.

- Essen 1917, p. 113.

- Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 108–109.

- Dit zijn wij, 44 Limburgse helmen Article in Dutch

- Groote Oorlog 1914–1918 Article in Dutch

- 44 helmen Wereldoorlog I vanaf nu in Halen Article in Dutch

References

Books

- Brose, E. D. (2001). The Kaiser's Army: The Politics of Military Technology in Germany during the Machine Age, 1870–1918. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517945-3.

- Essen, L. J. van der (1917). The Invasion and the War in Belgium from Liège to the Yser. London: T. F. Unwin. OCLC 800487618. Retrieved 4 January 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg: 1914 The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. I. Part 1. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 7 February 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- Strachan, H. (2001). To Arms. The First World War. I (pbk. ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- The war of 1914: Military Operations of Belgium in Defence of the Country and to Uphold Her Neutrality. London: W. H. & L Collingridge. 1915. OCLC 8651831. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

Websites

- Duffy, M. (2009). "The Battle of Halen, 1914". Battles–the Western Front. firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- Hove, P. van den (2014). "Halen, 12th of August, 1914: A Forgotten Battle in a Forgotten Landscape?". Brussels: Flanders Heritage Agency. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

Further reading

- Robinson, J.; Hendricks, F.; Robinson, J. (2015). The Last Great Cavalry Charge: The Battle of the Silver Helmets, Halen 12 August 1914. Stroud: Fonthill. ISBN 978-1-78155-183-7.

- Witte, J. B. (1920). Halen (12 août 1914) [Halen (12 August 1914)] (in French). Bruxelles: A. Dewit. OCLC 38775780.

- Young, G. W. (1914). From the Trenches: Louvain to the Aisne, the First Record of an Eye-Witness. London: T. F. Unwin. OCLC 504166646. Retrieved 26 November 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Haelen (1914). |