Battle of Grand Couronné

The Battle of Grand Couronné (French: Bataille du Grand Couronné) from 4 to 13 September 1914, took place in France after the Battle of the Frontiers, at the beginning of the First World War. After the German victories of Sarrebourg and Morhange, pursuit by the German 6th Army (Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria) and the 7th Army, took four days to regain contact with the French and attack to break through French defences on the Moselle.

| Battle of Grand Couronné | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Frontiers on the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Grand Couronné, September 1914 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Second Army | 6th Army | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 30,000 | |||||||

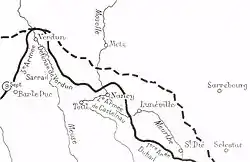

From 24 August to 13 September, the Battle of the Trouée de Charmes (24–28 August) when the German offensive was met by a French counter-offensive, a period of preparation from 28 August to 3 September, when part of the French eastern armies was moved westwards towards Paris, then a final German attack against the Grand Couronné de Nancy, fought from 4 to 13 September 1914 by the 6th Army and the French Second Army (Noël de Castelnau).

Background

After the failure of the French offensives in the Battle of Lorraine on 20 August 1914, the French Second Army was ordered by Joffre, on 22 August, to retreat to the Grand Couronné de Nancy, heights near Nancy, on an arc from Pont-à-Mousson to Champenoux, Lunéville and Dombasle-sur-Meurthe, to defend the position at all costs.[1] On 24 August, Rupprecht and the 6th Army tried to break through the French lines on the Moselle from Toul to Épinal and encircle Nancy. After the Battle of the Mortagne, an attempt by the Germans to advance at the junction of the French First and Second armies.[2]

A lull followed from 28 August to 3 September, then the Germans simultaneously attacked Saint-Dié and Nancy in the Battle of Grand Couronné.[2] After the failure of the Battle of Mortagne, the capture of Nancy would have been an important German psychological victory and the German Emperor Wilhelm II came to supervise the offensive. The German attack was part of an offensive of all the German armies in France in early September; a German success would have outflanked the right of the French armies from the east. Castelnau had to send several divisions westwards to reinforce the Third Army.[3]

Prelude

German offensive preparations

From the end of the Battle of the Trouée de Charmes on 28 August, Rupprecht and his Chief of Staff Konrad Krafft von Dellmensingen obtained more heavy artillery and managed to prevent the transfer of troops to the Eastern Front. Helmuth von Moltke the Younger wanted attacks by the German armies on the eastern flank to resume, preventing the French from withdrawing troops to the western flank near Paris. German preparations were sufficiently advanced for the offensive to begin during the night of 3 September.[4]

French defensive preparations

Castelnau concluded that the losses of the Second Army and the withdrawal of forces, to reinforce the Third Army, made it unlikely that the Second Army could withstand another German attack and submitted a memorandum to Joffre with the alternatives of fighting the battle without withdrawal, which would exhaust his forces or falling back to two successive defensive positions, which would cover the right flank of the French armies from Verdun to Paris and delay the German advance.[5]

Battle

The German offensive began during the night of 3/4 September, against the fortifications of the Grand Couronné on either side of Nancy, which pushed back the 2nd Group of Reserve Divisions (General Léon Durand) to the north and the XX Corps (General Maurice Balfourier) to the south, by the evening of 4 September.[6][lower-alpha 1] In the afternoon of 5 September, Castelnau telegraphed to Joffre that he proposed to evacuate Nancy, rather than hold ground, to preserve the fighting power of the army. Next day Joffre replied that the Second Army was to hold the area east of Nancy if at all possible and only then retire to a line from the Forest of Haye to Saffais, Belchamp and Borville.[6]

The civilian authorities in the city had begun preparations for an evacuation but the troops on the Grand Couronné repulsed German attacks on the right flank during 5 September. To the east and north of Nancy, the Reserve divisions were only pushed back a short distance. An attempt by Moltke to withdraw troops from the 6th Army, to join a new 7th Army being formed for operations on the Oise failed, when Rupprecht and Dellmensingen objected and were backed by the Emperor, who was at the 6th Army headquarters.[6][lower-alpha 2] German attacks continued on 6 September and the XX Corps conducted a counter-attack, which gave the defenders a short period to recuperate but the troops of the 2nd Group of Reserve Divisions, east and north of Nancy began to give way.[7]

On 7 September, German attacks further north drove a salient into the French defences south of Verdun at St. Mihiel, which threatened to separate the Second and Third armies.[8] At Nancy, part of the 59th Reserve Division retreated from the height of St Geneviève, which overlooked the Grand Couronné to the north-west of Nancy, exposing the left flank of the Second Army and Nancy to envelopment. Castelnau prepared to withdraw and abandon Nancy but was circumvented by the Second Army staff, who contacted Joffre and Castelnau was ordered to maintain the defence of the Grand Couronné for another 24 hours. (Castelnau had received news that a son had been killed, giving the orders while still shocked.)[7]

The French abandonment of the height of St Geneviève went unnoticed by the Germans, who had retired during the afternoon and the height was reoccupied before they could react. German attacks continued until the morning of 8 September, then diminished as Moltke began to withdraw troops to the right (west) flank of the German armies. Moltke sent Major Roeder, from his staff to the 6th Army, with orders to end the offensive and prepare to retire to the frontier; only at this point did Rupprecht find out that the armies near Paris were under severe pressure. On 10 September, the 6th Army began to withdraw to the east.[9] On 13 September, Pont-à-Mousson and Lunéville were re-occupied by the French unopposed and the French armies closed up to the Seille river, where the front stabilised until 1918.[10]

Aftermath

Analysis

The battles near Nancy contributed to the Allied success at the First Battle of the Marne, by fixing a large number of German troops in Lorraine. German attempts to break through between Toul and Épinal were costly in manpower and supplies, which might have had more effect elsewhere. The German offensives failed and were not able to prevent Joffre from moving troops westwards to outnumber the German armies near Paris.[11]

Casualties

In 2009, Holger Herwig wrote that in September, the 6th Army suffered 28,957 casualties, with 6,687 men killed, despite half the army being en route to Belgium; most lost in the fighting at the Grand Couronné. The 7th Army suffered 31,887 casualties, of which 10,384 men killed. The German army never calculated a definitive casualty list for the fighting in Alsace and Lorraine but the Bavarian official historian Karl Deuringer made a guess of 60 per cent casualties, of which 15 per cent were killed, in the fifty infantry brigades which fought in the region, which would amount to 66,000 casualties, 17,000 killed, which the Verlustliste (ten-day casualty reports) bore out.[12]

Notes

Footnotes

- Spears 1999, p. 425.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 215–216.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 242–243.

- Tyng 2007, pp. 314–315.

- Tyng 2007, p. 315.

- Tyng 2007, pp. 316–317.

- Tyng 2007, p. 317.

- Spears 1999, pp. 551–552, 554.

- Tyng 2007, pp. 318–319.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 253, 257.

- Tyng 2007, p. 319.

- Herwig 2009, pp. 217–218.

References

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- Spears, E. (1999) [1968]. Liaison 1914 (2nd, Cassell, London ed.). London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 978-0-304-35228-9.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme, Yardley, PA ed.). New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-1-59416-042-4.

Further reading

- Der Herbst-Feldzug 1914: Im Westen bis zum Stellungskrieg, im Osten bis zum Rückzug [The Autumn Campaign 1914: In the West to Position Warfare, in the East to the Retreat]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande [The World War 1914–1918: Military Operations on Land]. V (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler & Sohn. 2012 [1929]. OCLC 838299944. Retrieved 12 February 2014 – via Die Digitale Landesbibliothek Oberösterreich.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich Von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg: 1914 The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. I. Part 1. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Keegan, J. (2000). The First World War. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-70045-3.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Grand Couronné. |