Agriculture in India

The history of Agriculture in India dates back to Indus Valley Civilization and even before that in some places of Southern India.[1] India ranks second worldwide in farm outputs. As per 2018, agriculture employed more than 50% of the Indian work force and contributed 17–18% to country's GDP.[2]

In 2016, agriculture and allied sectors like animal husbandry, forestry and fisheries accounted for 15.4% of the GDP (gross domestic product) with about 41.49% of the workforce in 2020.[3][4][5][6] India ranks first in the world with highest net cropped area followed by US and China.[7] The economic contribution of agriculture to India's GDP is steadily declining with the country's broad-based economic growth. Still, agriculture is demographically the broadest economic sector and plays a significant role in the overall socio-economic fabric of India.

India exported $38 billion worth of agricultural products in 2013, making it the seventh largest agricultural exporter worldwide and the sixth largest net exporter.[8] Most of its agriculture exports serve developing and least developed nations.[8] Indian agricultural/horticultural and processed foods are exported to more than 120 countries, primarily to the Japan, Southeast Asia, SAARC countries, the European Union and the United States.[9][10]

Overview

As per the 2014 FAO world agriculture statistics India is the world's largest producer of many fresh fruits like banana, mango, guava, papaya, lemon and vegetables like chickpea, okra and milk, major spices like chili pepper, ginger, fibrous crops such as jute, staples such as millets and castor oil seed. India is the second largest producer of wheat and rice, the world's major food staples.[11]

India is currently the world's second largest producer of several dry fruits, agriculture-based textile raw materials, roots and tuber crops, pulses, farmed fish, eggs, coconut, sugarcane and numerous vegetables. India is ranked under the world's five largest producers of over 80% of agricultural produce items, including many cash crops such as coffee and cotton, in 2010.[11] India is one of the world's five largest producers of livestock and poultry meat, with one of the fastest growth rates, as of 2011.[12]

One report from 2008 claimed that India's population is growing faster than its ability to produce rice and wheat.[13] While other recent studies claim that India can easily feed its growing population, plus produce wheat and rice for global exports, if it can reduce food staple spoilage/wastage, improve its infrastructure and raise its farm productivity like those achieved by other developing countries such as Brazil and China.[14][15]

In fiscal year ending June 2011, with a normal monsoon season, Indian agriculture accomplished an all-time record production of 85.9 million tonnes of wheat, a 6.4% increase from a year earlier. Rice output in India hit a new record at 95.3 million tonnes, a 7% increase from the year earlier.[16] Lentils and many other food staples production also increased year over year. Indian farmers, thus produced about 71 kilograms of wheat and 80 kilograms of rice for every member of Indian population in 2011. The per capita supply of rice every year in India is now higher than the per capita consumption of rice every year in Japan.[17]

India exported $39 billion worth of agricultural products in 2013, making it the seventh largest agricultural exporter worldwide, and the sixth largest net exporter.[8] This represents explosive growth, as in 2004 net exports were about $5 billion.[8] India is the fastest growing exporter of agricultural products over a 10-year period, its $39 billion of net export is more than double the combined exports of the European Union (EU-28).[8] It has become one of the world's largest supplier of rice, cotton, sugar and wheat. India exported around 2 million metric tonnes of wheat and 2.1 million metric tonnes of rice in 2011 to Africa, Nepal, Bangladesh and other regions around the world.[16]

Aquaculture and catch fishery is amongst the fastest growing industries in India. Between 1990 and 2010, the Indian fish capture harvest doubled, while aquaculture harvest tripled. In 2008, India was the world's sixth largest producer of marine and freshwater capture fisheries and the second largest aquaculture farmed fish producer. India exported 600,000 metric tonnes of fish products to nearly half of the world's countries.[18][19][20] Though the available nutritional standard is 100% of the requirement, India lags far behind in terms of quality protein intake at 20% which is to be tackled by making available protein rich food products such as eggs, meat, fish, chicken etc. at affordable prices[21]

India has shown a steady average nationwide annual increase in the kilograms produced per hectare for some agricultural items, over the last 60 years. These gains have come mainly from India's green revolution, improving road and power generation infrastructure, knowledge of gains and reforms.[22] Despite these recent accomplishments, agriculture has the potential for major productivity and total output gains, because crop yields in India are still just 30% to 60% of the best sustainable crop yields achievable in the farms of developed and other developing countries.[23] Additionally, post harvest losses due to poor infrastructure and unorganised retail, caused India to experience some of the highest food losses in the world.[24][25]

History

Vedic literature provides some of the earliest written record of agriculture in India. Rigveda hymns, for example, describes plowing, fallowing, irrigation, fruit and vegetable cultivation. Other historical evidence suggests rice and cotton were cultivated in the Indus Valley, and plowing patterns from the Bronze Age have been excavated at Kalibangan in Rajasthan.[26] Bhumivargaha, an Indian Sanskrit text, suggested to be 2500 years old, classifies agricultural land into 12 categories: urvara (fertile), ushara (barren), maru (desert), aprahata (fallow), shadvala (grassy), pankikala (muddy), jalaprayah (watery), kachchaha (contiguous to water), sharkara (full of pebbles and pieces of limestone), sharkaravati (sandy), nadimatruka (watered from a river), and devamatruka (rainfed). Some archaeologists believe that rice was a domesticated crop along the banks of the river Ganges in the sixth millennium BC.[27] So were species of winter cereals (barley, oats, and wheat) and legumes (lentil and chickpea) grown in northwest India before the sixth millennium BC. Other crops cultivated in India 3000 to 6000 years ago, include sesame, linseed, safflower, mustard, castor, mung bean, black gram, horse gram, pigeon pea, field pea, grass pea (khesari), fenugreek, cotton, jujube, grapes, dates, jack fruit, mango, mulberry, and black plum. Indians might have domesticated buffalo (the river type) 5000 years ago.[28]

According to some scientists agriculture was widespread in the Indian peninsula, 10000–3000 years ago, well beyond the fertile plains of the north. For example, one study reports 12 sites in the southern Indian states of [Tamil Nadu], [Andhra Pradesh]and [Karnataka] providing clear evidence of agriculture of pulses [Vigna radiata] and [Macrotyloma uniflorum], millet-grasses (Brachiaria ramosa and Setaria verticillata), wheats (Triticum dicoccum, Triticum durum/aestivum), barley (Hordeum vulgare), hyacinth bean (Lablab purpureus), pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), finger millet (Eleusine coracana), cotton (Gossypium sp.), linseed (Linum sp.), as well as gathered fruits of Ziziphus and two Cucurbitaceae.[29][30]

Some claim Indian agriculture began by 9000 BC as a result of early cultivation of plants, and domestication of crops and animals.[31] Settled life soon followed with implements and techniques being developed for agriculture.[32][33] Double monsoons led to two harvests being reaped in one year.[34] Indian products soon reached trading networks and foreign crops were introduced.[34][35] Plants and animals—considered essential to survival by the Indians—came to be worshiped and venerated.[31]

The middle ages saw irrigation channels reach a new level of sophistication, and Indian crops affected the economies of other regions of the world under Islamic patronage.[36][37] Land and water management systems were developed with an aim of providing uniform growth.[38][39]

Despite some stagnation during the later modern era the independent Republic of India was able to develop a comprehensive agricultural programme.[40][41]

Agriculture and colonialism

Over 2500 years ago, Indian farmers had discovered and begun farming many spices and sugarcane. It was in India, between the sixth and four BC, that the Persians, followed by the Greeks, discovered the famous "reeds that produce honey without bees" being grown. These were locally called साखर, (Sākhara). On their return journey, the Macedonian soldiers carried the "honey bearing reeds," thus spreading sugar and sugarcane agriculture.[42][43] People in India had invented, by about 500 BC, the process to produce sugar crystals. In the local language, these crystals were called khanda (खण्ड), which is the source of the word candy.[44]

Before the 18th century, cultivation of sugarcane was largely confined to India. A few merchants began to trade in sugar – a luxury and an expensive spice in Europe until the 18th century. Sugar became widely popular in 18th-century Europe, then graduated to become a human necessity in the 19th century all over the world. This evolution of taste and demand for sugar as an essential food ingredient unleashed major economic and social changes. Sugarcane does not grow in cold, frost-prone climate; therefore, tropical and semitropical colonies were sought. Sugarcane plantations, just like cotton farms, became a major driver of large and forced human migrations in the 19th century and early 20th century – of people from Africa and from India, both in millions – influencing the ethnic mix, political conflicts and cultural evolution of Caribbean, South American, Indian Ocean and Pacific Island nations.[45][46]

The history and past accomplishments of Indian agriculture thus influenced, in part, colonialism, slavery and slavery-like indentured labour practices in the new world, Caribbean wars and world history in 18th and 19th centuries.[47][48][49][50][51]

Indian agriculture after independence

In the years since its independence, India has made immense progress towards food security. Indian population has tripled, and food-grain production more than quadrupled. There has been a substantial increase in available food-grain per capita.

Before the mid-1960s, India relied on imports and food aid to meet domestic requirements. However, two years of severe drought in 1965 and 1966 convinced India to reform its agricultural policy and that it could not rely on foreign aid and imports for food security. India adopted significant policy reforms focused on the goal of food grain self-sufficiency. This ushered in India's Green Revolution. It began with the decision to adopt superior yielding, disease resistant wheat varieties in combination with better farming knowledge to improve productivity. The state of Punjab led India's green revolution and earned the distinction of being the country's breadbasket.[53]

The initial increase in production was centred on the irrigated areas of the states of Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh. With the farmers and the government officials focusing on farm productivity and knowledge transfer, India's total food grain production soared. A hectare of Indian wheat farm that produced an average of 0.8 tonnes in 1948, produced 4.7 tonnes of wheat in 1975 from the same land. Such rapid growth in farm productivity enabled India to become self-sufficient by the 1970s. It also empowered the smallholder farmers to seek further means to increase food staples produced per hectare. By 2000, Indian farms were adopting wheat varieties capable of yielding 6 tonnes of wheat per hectare.[14][54]

With agricultural policy success in wheat, India's Green Revolution technology spread to rice. However, since irrigation infrastructure was very poor, Indian farmers innovated with tube-wells, to harvest ground water. When gains from the new technology reached their limits in the states of initial adoption, the technology spread in the 1970s and 1980s to the states of eastern India — Bihar, Odisha and West Bengal. The lasting benefits of the improved seeds and new technology extended principally to the irrigated areas which account for about one-third of the harvested crop area. In the 1980s, Indian agriculture policy shifted to "evolution of a production pattern in line with the demand pattern" leading to a shift in emphasis to other agricultural commodities like oilseed, fruit and vegetables. Farmers began adopting improved methods and technologies in dairying, fisheries and livestock, and meeting the diversified food needs of a growing population.

As with rice, the lasting benefits of improved seeds and improved farming technologies now largely depends on whether India develops infrastructure such as irrigation network, flood control systems, reliable electricity production capacity, all-season rural and urban highways, cold storage to prevent spoilage, modern retail, and competitive buyers of produce from Indian farmers. This is increasingly the focus of Indian agriculture policy.

India ranks 74 out of 113 major countries in terms of food security index.[21] India's agricultural economy is undergoing structural changes. Between 1970 and 2011, the GDP share of agriculture has fallen from 43% to 16%. This isn't because of reduced importance of agriculture or a consequence of agricultural policy; rather, it is largely due to the rapid economic growth in services, industrial output, and non-agricultural sectors in India between 2000 and 2010.

Agricultural scientist MS Swaminathan has played a vital role in the green revolution. In 2013, NDTV named him one of 25 living legends of India for outstanding contributions to agriculture and making India a food-sovereign country.

Two states, Sikkim[55][56][57][58] and Kerala[59][60] have planned to shift fully to organic farming by 2015 and 2016 respectively.

Irrigation

Indian irrigation infrastructure includes a network of major and minor canals from rivers, groundwater well-based systems, tanks, and other rainwater harvesting projects for agricultural activities. Of these, the groundwater system is the largest.[61] Of the 160 million hectares of cultivated land in India, about 39 million hectare can be irrigated by groundwater wells and an additional 22 million hectares by irrigation canals.[62] In 2010, only about 35% of agricultural land in India was reliably irrigated.[63] About 2/3rd cultivated land in India is dependent on monsoons.[64] The improvements in irrigation infrastructure in the last 50 years have helped India improve food security, reduce dependence on monsoons, improve agricultural productivity and create rural job opportunities. Dams used for irrigation projects have helped provide drinking water to a growing rural population, control flood and prevent drought-related damage to agriculture.[65] However, free electricity and attractive minimum support price for water intensive crops such as sugarcane and rice have encouraged ground water mining leading to groundwater depletion and poor water quality.[66] A news report in 2019 states that more than 60% of the water available for farming in India is consumed by rice and sugar, two crops that occupy 24% of the cultivable area.[67]

Output

As of 2011, India had a large and diverse agricultural sector, accounting, on average, for about 16% of GDP and 10% of export earnings. India's arable land area of 159.7 million hectares (394.6 million acres) is the second largest in the world, after the United States. Its gross irrigated crop area of 82.6 million hectares (215.6 million acres) is the largest in the world. India is among the top three global producers of many crops, including wheat, rice, pulses, cotton, peanuts, fruits and vegetables. Worldwide, as of 2011, India had the largest herds of buffalo and cattle, is the largest producer of milk and has one of the largest and fastest growing poultry industries.[68]

Major products and yields

The following table presents the 20 most important agricultural products in India, by economic value, in 2009. Included in the table is the average productivity of India's farms for each produce. For context and comparison, included is the average of the most productive farms in the world and name of country where the most productive farms existed in 2010. The table suggests India has large potential for further accomplishments from productivity increases, in increased agricultural output and agricultural incomes.[69][70]

| Rank | Commodity | Value (US$, 2016) | Unit price (US$ / kilogram, 2009) |

Average yield (tonnes per hectare, 2017) |

Most productive country (tonnes per hectare, 2017) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rice | $70.18 billion | 0.27 | 3.85 | 9.82 | Australia |

| 2 | Buffalo milk | $43.09 billion | 0.4 | 2.00[73] | 2.00[73] | India |

| 3 | Cow milk | $32.55 billion | 0.31 | 1.2[73] | 10.3[73] | Israel |

| 4 | Wheat | $26.06 billion | 0.15 | 2.8 | 8.9 | Netherlands |

| 5 | Cotton (Lint + Seeds) | $23.30 billion | 1.43 | 1.6 | 4.6 | Israel |

| 6 | Mangoes, guavas | $14.52 billion | 0.6 | 6.3 | 40.6 | Cape Verde |

| 7 | Fresh Vegetables | $11.87 billion | 0.19 | 13.4 | 76.8 | United States |

| 8 | Chicken meat | $9.32 billion | 0.64 | 10.6 | 20.2 | Cyprus |

| 9 | Potatoes | $8.23 billion | 0.15 | 19.9 | 44.3 | United States |

| 10 | Banana | $8.13 billion | 0.28 | 37.8 | 59.3 | Indonesia |

| 11 | Sugar cane | $7.44 billion | 0.03 | 66 | 125 | Peru |

| 12 | Maize | $5.81 billion | 0.42 | 1.1 | 5.5 | Nicaragua |

| 13 | Oranges | $5.62 billion | ||||

| 14 | Tomatoes | $5.50 billion | 0.37 | 19.3 | 55.9 | China |

| 15 | Chick peas | $5.40 billion | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.8 | China |

| 16 | Okra | $5.25 billion | 0.35 | 7.6 | 23.9 | Israel |

| 17 | Soybeans | $5.13 billion | 0.26 | 1.1 | 3.7 | Turkey |

| 18 | Hen eggs | $4.64 billion | 2.7 | 0.1[73] | 0.42[73] | Japan |

| 19 | Cauliflower and Broccoli | $4.33 billion | 2.69 | 0.138[73] | 0.424[73] | Thailand |

| 20 | Onions | $4.05 billion | 0.21 | 16.6 | 67.3 | Ireland |

As per FAOSTAT data, India produces various agriculture products in following values:[74]

| Number | Item | Production (in tonnes) |

| 1 | Apples | 2316000 |

| 2 | Bananas | 30460000 |

| 3 | Beans, green | 725998 |

| 4 | Carrots and turnips | |

| 5 | Cashew nuts, with shell | 743000 |

| 6 | Castor oil seed | 1196680 |

| 7 | Cauliflowers and broccoli | 9083000 |

| 8 | Cherries | 11107 |

| 9 | Chick peas | 9937990 |

| 10 | Chillies and peppers, dry | 1743000 |

| 11 | Chillies and peppers, green | 81837 |

| 12 | Coconuts | 14682000 |

| 13 | Coffee, green | 319500 |

| 14 | Cucumbers and gherkins | 199018 |

| 15 | Garlic | 2910000 |

| 16 | Ginger | 1788000 |

| 17 | Grapes | 3041000 |

| 18 | Lemons and limes | 3482000 |

| 19 | Mangoes, mangosteens, guavas | 25631000 |

| 20 | Melons, other (inc.cantaloupes) | 1266000 |

| 21 | Mushrooms and truffles | 182000 |

| 22 | Oilseeds nes | 42000 |

| 23 | Onions, dry | 22819000 |

| 24 | Oranges | 9509000 |

| 25 | Papayas | 6050000 |

| 26 | Peaches and nectarines | |

| 27 | Pears | 300000 |

| 28 | Pineapples | 1711000 |

| 29 | Potatoes | 50190000 |

| 30 | Rice, paddy | 177645000 |

| 31 | Soybeans | 13267520 |

| 32 | Sugar cane | 405416180 |

| 33 | Sweet potatoes | 1156000 |

| 34 | Tea | 1390080 |

| 35 | Tobacco, unmanufactured | 804454 |

| 36 | Tomatoes | 19007000 |

| 37 | Watermelons | 2495000 |

| 38 | Wheat | 103596230 |

The Statistics Office of the Food and Agriculture Organization reported that, per final numbers for 2009, India had grown to become the world's largest producer of the following agricultural products:[75][76]

- Fresh Fruit

- Lemons and limes

- Buffalo milk, whole, fresh

- Castor oil seeds

- Sunflower seeds

- Sorghum

- Millet

- Spices

- Okra

- Jute

- Beeswax

- Bananas

- Mangoes, mangosteens, guavas

- Pulses

- Indigenous buffalo meat

- Fruit, tropical

- Ginger

- Chick peas

- Areca nuts

- Other bastfibres

- Pigeon peas

- Papayas

- Chillies and peppers, dry

- Anise, badian, fennel, coriander

- Goat milk, whole, fresh

Per final numbers for 2009, India is the world's second largest producer of the following agricultural products:[75]

- Wheat

- Rice

- Fresh vegetables

- Sugar cane

- Groundnuts, with shell

- Lentils

- Garlic

- Cauliflowers and broccoli

- Peas, green

- Sesame seed

- Cashew nuts, with shell

- Silk-worm cocoons, reelable

- Cow milk, whole, fresh

- Tea

- Potatoes

- Onions

- Cotton lint

- Cotton seed

- Eggplants (aubergines)

- Nutmeg, mace and cardamoms

- Indigenous goat meat

- Cabbages and other brassicas

- Pumpkins, squash and gourds

In 2009, India was the world's third largest producer of eggs, oranges, coconuts, tomatoes, peas and beans.[75]

In addition to growth in total output, agriculture in India has shown an increase in average agricultural output per hectare in last 60 years. The table below presents average farm productivity in India over three farming years for some crops. Improving road and power generation infrastructure, knowledge gains and reforms has allowed India to increase farm productivity between 40% to 500% over 40 years.[22] India's recent accomplishments in crop yields while being impressive, are still just 30% to 60% of the best crop yields achievable in the farms of developed as well as other developing countries. Additionally, despite these gains in farm productivity, losses after harvest due to poor infrastructure and unorganised retail cause India to experience some of the highest food losses in the world.

| Crop[22] | Average YIELD, 1970–1971 | Average YIELD, 1990–1991 | Average YIELD, 2010–2011 | Average Yield, 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kilogram per hectare | kilogram per hectare | kilogram per hectare[77] | kilogram per hectare [78] | |

| Rice | 1123 | 1740 | 2240 | 4057.7 |

| Wheat | 1307 | 2281 | 2938 | 3533.4 |

| Pulses | 524 | 578 | 689 | 441.3 |

| Oilseeds | 579 | 771 | 1325 | 1592.8 |

| Sugarcane | 48322 | 65395 | 68596 | 80104.5 |

| Tea | 1182 | 1652 | 1669 | 2212.8 |

| Cotton | 106 | 225 | 510 | 1156.6 |

Production of Crop for various years (in Thousands of hectare)

| Crop | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

| Rice | 34694 | 34694 | 40708.4 | 42648.7 | 44900 | 44010 |

| Wheat | 12927 | 18240.5 | 22278.8 | 24167.1 | 25730.6 | 29068.6 |

| Pulses | 3592 | 2582.8 | 2388 | 2123.1 | 1650 | 1700 |

| Oil seeds | 486 | 453.3 | 557.5 | 557.5 | 716.7 | 1471 |

| Sugar cane | 2413 | 2615 | 2666.6 | 3686 | 4315.7 | 4944.39 |

| Tea | 331.229 | 358.675 | 384.242 | 421 | 504 | 600 |

| Cotton | 7719 | 7800 | 8057.4 | 7661.4 | 9100 | 12178 |

India and China are competing to establish the world record on rice yields. Yuan Longping of China National Hybrid Rice Research and Development Centre set a world record for rice yield in 2010 at 19 tonnes per hectare in a demonstration plot. In 2011, this record was surpassed by an Indian farmer, Sumant Kumar, with 22.4 tonnes per hectare in Bihar, also in a demonstration plot. These farmers claim to have employed newly developed rice breeds and system of rice intensification (SRI), a recent innovation in farming. The claimed Chinese and Indian yields have yet to be demonstrated on 7 hectare farm lots and that these are reproducible over two consecutive years on the same farm.[80][81][82][83]

Horticulture

The total production and economic value of horticultural produce, such as fruits, vegetables and nuts has doubled in India over the 10-year period from 2002 to 2012. In 2012, the production from horticulture exceeded grain output for the first time. The total horticulture produce reached 277.4 million metric tonnes in 2013, making India the second largest producer of horticultural products after China.[84] Of this, India in 2013 produced 81 million tonnes of fruits, 162 million tonnes of vegetables, 5.7 million tonnes of spices, 17 million tonnes of nuts and plantation products (cashew, cacao, coconut, etc.), 1 million tonnes of aromatic horticulture produce and 1.7 million tonnes of flowers (7.6 billion cut flowers).[85][86]

| Country[87] | Area under fruits production (million hectares)[87] | Average Fruits Yield (Metric tonnes per hectare)[87] | Area under vegetable production (million hectares)[87] | Average Vegetable Yield (Metric tonnes per hectare)[87] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.0 | 11.6 | 9.2 | 52.36 | |

| 11.8 | 11.6 | 24.6 | 23.4 | |

| 1.54 | 9.1 | 0.32 | 39.3 | |

| 1.14 | 23.3 | 1.1 | 32.5 | |

| World | 57.3 | 11.3 | 60.0 | 19.7 |

During the 2013 fiscal year, India exported horticulture products worth ₹14,365 crore (US$2.0 billion), nearly double the value of its 2010 exports.[84] Along with these farm-level gains, the losses between farm and consumer increased and are estimated to range between 51 and 82 million metric tonnes a year.

Organic Agriculture

Organic agriculture has fed India for centuries and it is again a growing sector in India. Organic production offers clean and green production methods without the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides and it achieves a premium price in the market place. India has 6,50,000 organic producers, which is more that any other country.[88] India also has 4 million hectares of land certified as organic wildculture, which is third in the world (after Finland and Zambia).[89] As non availability of edible biomass is impeding the growth of animal husbandry in India, organic production of protein rich cattle, fish and poultry feed using biogas /methane/natural gas by cultivating Methylococcus capsulatus bacteria with tiny land and water foot print is a solution for ensuring adequate protein rich food to the population.[90][91][92][93]

Agriculture based cooperatives

India has seen a huge growth in cooperative societies, mainly in the farming sector, since 1947 when the country gained independence from Britain. The country has networks of cooperatives at the local, regional, state and national levels that assist in agricultural marketing. The commodities that are mostly handled are food grains, jute, cotton, sugar, milk, fruit and nuts[94] Support by the state government led to more than 25,000 cooperatives being set up by the 1990s in the state of Maharashtra.[95]

Sugar industry

Most of the sugar production in India takes place at mills owned by local cooperative societies.[96] The members of the society include all farmers, small and large, supplying sugarcane to the mill.[97] Over the last fifty years, the local sugar mills have played a crucial part in encouraging political participation and as a stepping stone for aspiring politicians.[98] This is particularly true in the state of Maharashtra where a large number of politicians belonging to the Congress party or NCP had ties to sugar cooperatives from their local area and has created a symbiotic relationship between the sugar factories and local politics.[99] However, the policy of "profits for the company but losses to be borne by the government", has made a number of these operations inefficient.[100][95]

Marketing

As with sugar, cooperatives play a significant part in the overall marketing of fruit and vegetables in India. Since the 1980s, the amount of produce handled by Cooperative societies has increased exponentially. Common fruit and vegetables marketed by the societies include bananas, mangoes, grapes, onions and many others.[101]

Dairy industry

Dairy farming based on the Amul Pattern, with a single marketing cooperative, is India's largest self-sustaining industry and its largest rural employment provider. Successful implementation of the Amul model has made India the world's largest milk producer.[102] Here small, marginal farmers with a couple or so heads of milch cattle queue up twice daily to pour milk from their small containers into the village union collection points. The milk after processing at the district unions is then marketed by the state cooperative federation nationally under the Amul brand name, India's largest food brand. With the Anand pattern three-fourth of the price paid by the mainly urban consumers goes into the hands of millions of small dairy farmers, who are the owners of the brand and the cooperative.[103]

Banking and rural credit

Cooperative banks play a great part in providing credit in rural parts of India. Just like the sugar cooperatives, these institutions serve as the power base for local politicians.[95]

Problems

"Slow agricultural growth is a concern for policymakers as some two-thirds of India's people depend on rural employment for a living. Current agricultural practices are neither economically nor environmentally sustainable and India's yields for many agricultural commodities are low. Poorly maintained irrigation systems and almost universal lack of good extension services are among the factors responsible. Farmers' access to markets is hampered by poor roads, rudimentary market infrastructure, and excessive regulation."

— World Bank: "India Country Overview 2008"[106]

"With a population of just over 1.3 billion, India is the world's largest democracy. In the past decade, the country has witnessed accelerated economic growth, emerged as a global player with the world's fourth largest economy in purchasing power parity terms, and made progress towards achieving most of the Millennium Development Goals. India's integration into the global economy has been accompanied by impressive economic growth that has brought significant economic and social benefits to the country. Nevertheless, disparities in income and human development are on the rise. Preliminary estimates suggest that in 2009–10 the combined all India poverty rate was 32 % compared to 37 % in 2004–05. Going forward, it will be essential for India to build a productive, competitive, and diversified agricultural sector and facilitate rural, non-farm entrepreneurship and employment. Encouraging policies that promote competition in agricultural marketing will ensure that farmers receive better prices."

— World Bank: "India Country Overview 2011"[15]

A 2003 analysis of India's agricultural growth from 1970 to 2001 by the Food and Agriculture Organization identified systemic problems in Indian agriculture. For food staples, the annual growth rate in production during the six-year segments 1970–76, 1976–82, 1982–88, 1988–1994, 1994–2000 were found to be respectively 2.5, 2.5, 3.0, 2.6, and 1.8% per annum. Corresponding analyses for the index of total agricultural production show a similar pattern, with the growth rate for 1994–2000 attaining only 1.5% per annum.[107]

The biggest problem of farmers is the low price for their farm produce. A recent study showed that proper pricing based on energy of production and equating farming wages to Industrial wages may be beneficial for the farmers.[108]

Infrastructure

India has very poor rural roads affecting timely supply of inputs and timely transfer of outputs from Indian farms. Irrigation systems are inadequate, leading to crop failures in some parts of the country because of lack of water. In other areas regional floods, poor seed quality and inefficient farming practices, lack of cold storage and harvest spoilage cause over 30% of farmer's produce going to waste, lack of organised retail and competing buyers thereby limiting Indian farmer's ability to sell the surplus and commercial crops.

The Indian farmer receives just 10% to 23% of the price the Indian consumer pays for exactly the same produce, the difference going to losses, inefficiencies and middlemen. Farmers in developed economies of Europe and the United States receive 64% to 81%.

Productivity

Although India has attained self-sufficiency in food staples, the productivity of its farms is below that of Brazil, the United States, France and other nations. Indian wheat farms, for example, produce about a third of the wheat per hectare per year compared to farms in France. Rice productivity in India was less than half that of China. Other staples productivity in India is similarly low. Indian total factor productivity growth remains below 2% per annum; in contrast, China's total factor productivity growths is about 6% per annum, even though China also has smallholding farmers. Several studies suggest India could eradicate its hunger and malnutrition and be a major source of food for the world by achieving productivity comparable with other countries.

By contrast, Indian farms in some regions post the best yields, for sugarcane, cassava and tea crops.[109]

Crop yields vary significantly between Indian states. Some states produce two to three times more grain per acre than others.

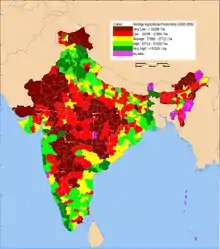

As the map shows, the traditional regions of high agricultural productivity in India are the north west (Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh), coastal districts on both coasts, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu. In recent years, the states of Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh in central India and Gujarat in the west have shown rapid agricultural growth.[110]

The table compares the statewide average yields for a few major agricultural crops in India, for 2001–2002.[111]

| Crop[111] | Average farm yield in Bihar | Average farm yield in Karnataka | Average farm yield in Punjab |

|---|---|---|---|

| kilogram per hectare | kilogram per hectare | kilogram per hectare | |

| Wheat | 2020 | unknown | 3880 |

| Rice | 1370 | 2380 | 3130 |

| Pulses | 610 | 470 | 820 |

| Oil seeds | 620 | 680 | 1200 |

| Sugarcane | 45510 | 79560 | 65300 |

Crop yields for some farms in India are within 90% of the best achieved yields by farms in developed countries such as the United States and in European Union. No single state of India is best in every crop. Tamil Nadu achieved highest yields in rice and sugarcane, Haryana in wheat and coarse grains, Karnataka in cotton, Bihar in pulses, while other states do well in horticulture, aquaculture, flower and fruit plantations. These differences in agricultural productivity are a function of local infrastructure, soil quality, micro-climates, local resources, farmer knowledge and innovations.[111]

The Indian food distribution system is highly inefficient. Movement of agricultural produce is heavily regulated, with inter-state and even inter-district restrictions on marketing and movement of agricultural goods.[111]

One study suggests Indian agricultural policy should best focus on improving rural infrastructure primarily in the form of irrigation and flood control infrastructure, knowledge transfer of better yielding and more disease resistant seeds. Additionally, cold storage, hygienic food packaging and efficient modern retail to reduce waste can improve output and rural incomes.[111]

The low productivity in India is a result of the following factors:

- The average size of land holdings is very small (less than 2 hectares) and is subject to fragmentation due to land ceiling acts, and in some cases, family disputes. Such small holdings are often over-manned, resulting in disguised unemployment and low productivity of labour. Some reports claim smallholder farming may not be cause of poor productivity, since the productivity is higher in China and many developing economies even though China smallholder farmers constitute over 97% of its farming population.[112] A Chinese smallholder farmer is able to rent his land to larger farmers, China's organised retail and extensive Chinese highways are able to provide the incentive and infrastructure necessary to its farmers for sharp increases in farm productivity.

- Adoption of modern agricultural practices and use of technology is inadequate in comparison with Green Revolution methods and technologies, hampered by ignorance of such practices, high costs and impracticality in the case of small land holdings.

- According to the World Bank, Indian branch's Priorities for Agriculture and Rural Development, India's large agricultural subsidies are hampering productivity-enhancing investment. This evaluation is based largely on a productivity agenda and does not take any ecological implications into account. According to a neo-liberal view, over-regulation of agriculture has increased costs, price risks and uncertainty because the government intervenes in labour, land, and credit markets. India has inadequate infrastructure and services.[113] The World Bank also says that the allocation of water is inefficient, unsustainable and inequitable. The irrigation infrastructure is deteriorating.[113] The overuse of water is being covered by over-pumping aquifers but, as these are falling by one foot of groundwater each year, this is a limited resource.[114] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report that food security may be a big problem in the region post 2030.[115]

- Illiteracy, general socio-economic backwardness, slow progress in implementing land reforms and inadequate or inefficient finance and marketing services for farm produce.

- Inconsistent government policy. Agricultural subsidies and taxes are often changed without notice for short term political ends.

- Irrigation facilities are inadequate, as revealed by the fact that only 52.6% of the land was irrigated in 2003–04,[116] which result in farmers still being dependent on rainfall, specifically the monsoon season. A good monsoon results in a robust growth for the economy, while a poor monsoon leads to a sluggish growth.[117] Farm credit is regulated by NABARD, which is the statutory apex agent for rural development in the subcontinent. At the same time, over-pumping made possible by subsidised electric power is leading to an alarming drop in aquifer levels.[118][119][120]

- A third of all food that is produced rots due to inefficient supply chains and the use of the "Walmart model" to improve efficiency is blocked by laws against foreign investment in the retail sector.[121]

Farmer suicides

In 2012, the National Crime Records Bureau of India reported 13,754 farmer suicides.[122] Farmer suicides account for 11.2% of all suicides in India.[122][123] Activists and scholars have offered a number of conflicting reasons for farmer suicides, such as monsoon failure, high debt burdens, genetically modified crops, government policies, public mental health, personal issues and family problems.[124][125][126]

Marketing

Agromarketing is poorly developed in India.[127]

Diversion of agricultural land for non-agricultural purpose

Indian National Policy for Farmers of 2007[128] stated that "prime farmland must be conserved for agriculture except under exceptional circumstances, provided that the agencies that are provided with agricultural land for non-agricultural projects should compensate for treatment and full development of equivalent degraded or wastelands elsewhere". The policy suggested that, as far as possible, land with low farming yields or that was not farmable should be earmarked for non-agricultural purposes such as construction, industrial parks and other commercial development.[128]

Amartya Sen offered a counter viewpoint, stating that "prohibiting the use of agricultural land for commercial and industrial development is ultimately self-defeating."[129] He stated that agricultural land may be better suited for non-agriculture purposes if industrial production could generate many times more than the value of the product produced by agriculture.[129] Sen suggested India needed to bring productive industry everywhere, wherever there are advantages of production, market needs and the locational preferences of managers, engineers, technical experts as well as unskilled labour because of education, healthcare and other infrastructure. He stated that instead of government controlling land allocation based on soil characteristics, the market economy should determine productive allocation of land.[129]

Please check the validity of the source listed above.

Initiatives

The required level of investment for the development of marketing, storage and cold storage infrastructure is estimated to be huge. The government has not been able to implement schemes to raise investment in marketing infrastructure. Among these schemes are 'Construction of Rural Godowns', 'Market Research and Information Network', and 'Development / Strengthening of Agricultural Marketing Infrastructure, Grading and Standardisation'.[130]

The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), established in 1905, was responsible for the search leading to the "Indian Green Revolution" of the 1970s. The ICAR is the apex body in agriculture and related allied fields, including research and education.[131] The Union Minister of Agriculture is the president of the ICAR. The Indian Agricultural Statistics Research Institute develops new techniques for the design of agricultural experiments, analyses data in agriculture, and specialises in statistical techniques for animal and plant breeding.

Recently (May 2016) the government of India has set up the Farmers Commission to completely evaluate the agriculture programme.[132] Its recommendations have had a mixed reception.

In November 2011, India announced major reforms in organised retail. These reforms would include logistics and retail of agricultural produce. The announcement led to major political controversy. The reforms were placed on hold by the government in December 2011.

In the summer of 2012, the subsidised electricity for pumping, which has caused an alarming drop in aquifer levels, put additional strain on the country's electrical grid due to a 19% drop in monsoon rains and may have contributed to a blackout across much of the country. In response the state of Bihar offered farmers over $100 million in subsidised diesel to operate their pumps.[133]

In 2015, Narendra Modi announced to double farmer's income by 2022.[134]

Startups with niche technology and new business models are working to solve problems in Indian agriculture and its marketing.[135] Kandawale is one of such e-commerce website which sells Indian Red Onions to bulk users direct from farmers, reducing unnecessary cost escalations.

Maps

Natural vegetation zones in India

Natural vegetation zones in India

See also

- Animal husbandry in India

- Beekeeping in India

- Rice production in India

- Retailing in India

- Farming Systems in India

- Fishing in India

- Women in agriculture in India

- Forestry in India

- Rural roads and infrastructure in India

- Irrigation in India

- Biotechnology in India

- eFarming by myKheti in India

- List of countries by employment in agriculture

Bibliography

- George A. Grierson (1885). Bihar Peasant Life. Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta.

References

- Brese, White (1993). "Agriculture".

- "India economic survey 2018: Farmers gain as agriculture mechanisation speeds up, but more R&D needed". The Financial Express. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "CIA Factbook: India-Economy". Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- Agriculture's share in GDP declines to 13.7% in 2012–13

- Staff, India Brand Equity Foundation Agriculture and Food in India Accessed 7 May 2013

- "Labor force by agriculture sector in India".

- "India outranks US, China with world's highest net cropland area". Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- India's Agricultural Exports Climb to Record High, United States Department of Agriculture (2014)

- "Agriculture in India: Agricultural Exports & Food Industry in India | IBEF".

- "Home". Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- "FAOSTAT, 2014 data". Faostat.fao.org. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Livestock and Poultry: World Markets & Trade" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. October 2011.

- Sengupta, Somini (22 June 2008). "The Food Chain in Fertile India, Growth Outstrips Agriculture". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Rapid growth of select Asian economies". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2009.

- "India Country Overview 2011". World Bank. 2011. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- "India Allows Wheat Exports for the First Time in Four Years". Bloomberg L.P. 8 September 2011.

- "Fish and Rice in the Japanese Diet". Japan Review. 2006. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- "The state of world fisheries and aquaculture, 2010" (PDF). FAO of the United Nations. 2010.

- "Export of marine products from India (see statistics section)". Central Institute of Fisheries Technology, India. 2008. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013.

- "Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles: India". Food and Africulture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011.

- "India: Global Food Security Index". Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy". Reserve Bank of India: India's Central Bank. 2011.

- "World Wheat, Corn and Rice". Oklahoma State University, FAOSTAT. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015.

- "Indian retail: The supermarket's last frontier". The Economist. 3 December 2011.

- Sinha, R.K. (2010). "Emerging Trends, Challenges and Opportunities presentation, on publications page, see slides 7 through 21". National Seed Association of India. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "The Story of India: a PBS documentary". Public Broadcasting Service, United States.

- Roy, Mira (2009). "Agriculture in the Vedic Period" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 44 (4): 497–520. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Indian Agriculture and IFFCO" (PDF). Quebec Reference Center for Agriculture and Agri-food. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Fuller; Korisettar, Ravi; Venkatasubbaiah, P.C.; Jones, Martink.; et al. (2004). "Early plant domestications in southern India: some preliminary archaeobotanical results" (PDF). Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 13 (2): 115–129. doi:10.1007/s00334-004-0036-9. S2CID 8108444. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- Tamboli and Nene. "Science in India with Special Reference to Agriculture" (PDF). Agri History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- Gupta, p. 57

- Harris & Gosden, p. 385

- Lal, R. (August 2001). "Thematic evolution of ISTRO: transition in scientific issues and research focus from 1955 to 2000". Soil and Tillage Research. 61 (1–2): 3–12 [3]. doi:10.1016/S0167-1987(01)00184-2.

- agriculture, history of. Encyclopædia Britannica 2008.

- Shaffer, pp. 310–311

- Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui, "Water Works and Irrigation System in India during Pre-Mughal Times", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Feb. 1986), pp. 52–77.

- Shaffer, p. 315

- Palat, p. 63

- Kumar, p. 182

- Roy 2006

- Kumar 2006

- Rolph, George (1873). Something about sugar: its history, growth, manufacture and distribution.

- "Agribusiness Handbook: Sugar beet white sugar". Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. 2009.

- "Sugarcane: Saccharum Officinarum" (PDF). USAID, Govt of United States. 2006. p. 7.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2013. Alt URL

- Mintz, Sidney (1986). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-009233-2.

- "Indian indentured labourers". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- "Forced Labour". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- Laurence, K (1994). A Question of Labour: Indentured Immigration Into Trinidad & British Guiana, 1875–1917. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12172-3.

- "St. Lucia's Indian Arrival Day". Caribbean Repeating Islands. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- Lai, Walton (1993). Indentured labor, Caribbean sugar: Chinese and Indian migrants to the British West Indies, 1838–1918. ISBN 978-0-8018-7746-9.

- Steven Vertovik (Robin Cohen, ed.) (1995). The Cambridge survey of world migration. Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-0-521-44405-7.

- The Government of Punjab (2004). Human Development Report 2004, Punjab (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011. Section: "The Green Revolution", pp. 17–20.

- The Government of Punjab (2004). Human Development Report 2004, Punjab (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011. Section: "The Green Revolution", pp. 17–20.

- "Brief history of wheat improvement in India". Directorate of Wheat Research, ICAR India. 2011.

- "Sikkim to become a completely organic state by 2015". The Hindu. 9 September 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "Sikkim makes an organic shift". Times of India. 7 May 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "Sikkim ‘livelihood schools' to promote organic farming" Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Hindu Business Line. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "Sikkim races on organic route". Telegraph India. 12 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Martin, K. a. (19 October 2014). "State to switch fully to organic farming by 2016: Mohanan". The Hindu.

- "CM: Will Get Total Organic Farming State Tag by 2016".

- S. Siebert et al. (2010), Groundwater use for irrigation – a global inventory, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 14, pp. 1863–1880

- Global map of irrigated areas: India FAO-United Nations and Bonn University, Germany (2013)

- Agricultural irrigated land (% of total agricultural land) The World Bank (2013)

- Economic Times: How to solve the problems of India's rain-dependent agricultural land

- National Water Development Agency Ministry of Water Resources, Govt of India (2014)

- "India's thirsty crops upset water equation". Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- Biswas, Soutik (2019). "India election 2019: How sugar influences the world's biggest vote". BBC.com (8 May 2019). BBC. BBC. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "India: Basic Information". United States Department of Agriculture – Economic Research Service. August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013.

- Adam Cagliarini and Anthony Rush (June 2011). "Bulletin: Economic Development and Agriculture in India" (PDF). Reserve Bank of Australia. pp. 15–22.

- "Food and Agricultural commodities production / Commodities by country / India". FAOSTAT. 2013.

- "Production / Crops / India". FAOSTAT. 2014.

- Tonnes per livestock animal

- "Agricultural Proudction in india, 2019".

- "Country Rank in the World, by commodity". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011.

- These are food and agriculture classification groups. For definition with list of botanical species covered under each classification, consult FAOSTAT of the United Nations; Link: http://faostat.fao.org/site/384/default.aspx

- Data checks suggest there is difference between FAO's statistics office and Reserve Bank of India estimates; these differences are small and may be because of the fiscal year start months.

- "India agriculture proction".

- "production of crops in India".

- L.P. Yuan (2010). "A Scientist's Perspective on Experience with SRI in CHINA for Raising the Yields of Super Hybrid Rice" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2011.

- "Indian farmer sets new world record in rice yield". The Philippine Star. 18 December 2011. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

- "Grassroots heroes lead Bihar's rural revolution". India Today. 10 January 2012.

- "System of Rice Intensification". Cornell University. 2011.

- Deficit rains spare horticulture, record production expected Livemint, S Bera, Hindustan Times (19 January 2015)

- Final Area & Production Estimates for Horticulture Crops for 2012–2013 Archived 6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Government of India (2014)

- Horticulture output Horticulture Board of India

- "Horticulture in India" (PDF). MOSPI, Government of India. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Paull, John & Hennig, Benjamin (2016) rider Vinay Kumar Atlas of Organics: Four Maps of the World of Organic Agriculture Journal of Organics. 3(1): 25–32.

- Paull, John (2016) Organics Olympiad 2016: Global Indices of Leadership in Organic Agriculture, Journal of Social and Development Sciences. 7(2):79–87

- "BioProtein Production" (PDF). Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals – and us". Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "New venture selects Cargill's Tennessee site to produce Calysta FeedKind® Protein". Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "Assessment of environmental impact of FeedKind protein" (PDF). Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Vadivelu, A. and Kiran, B.R., 2013. Problems and prospects of agricultural marketing in India: An overview. International journal of agricultural and food science, 3(3), pp.108–118.

- Dahiwale, S. M. (11 February 1995). "Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra". Economic and Political Weekly. 30 (6): 340–342. JSTOR 4402382.

- Biswas, Soutik (2019). "India election 2019: How sugar influences the world's biggest vote". BBC.com (8 May 2019). BBC. BBC. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "National Federation of Cooperative Sugar Factories Limited". Coopsugar.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Patil, Anil (9 July 2007). "Sugar cooperatives on death bed in Maharashtra". Rediff India. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Baviskar, edited by B.S.; Mathew, George (2008). Inclusion and exclusion in local governance : field studies from rural India. London: SAGE. p. 319. ISBN 9788178298603.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- http://www.helsinki.fi/iehc2006/papers2/Das72.pdf

- K. V. Subrahmanyam; T. M. Gajanana (2000). Cooperative Marketing of Fruits and Vegetables in India. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 45–60. ISBN 978-81-7022-820-2.

- Scholten, Bruce A. (2010). India's white revolution Operation Flood, food aid and development. London: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 10. ISBN 9781441676580.

- Damodaran, H., 2008. Patidars and Marathas. In India’s New Capitalists (pp. 216–258). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Global Tractor Market Analysis Available to AEM Members from Agrievolution Alliance Association of Equipment Manufacturers, Wisconsin, USA (2014)

- India proves fertile ground for tractor makers The Financial Times (8 April 2014) (subscription required)

- "India Country Overview 2008". World Bank. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- "SMALLHOLDER FARMERS IN INDIA: FOOD SECURITY AND AGRICULTURAL POLICY" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2003.

- How much should a fair price of farmer's produce be?

- Production Crops – Yield by Country Archived 14 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, FAO United Nations 2011

- Ashok Gulati; Pallavi Rajkhowa; Pravesh Sharma (April 2017). Making Rapid Strides- Agriculture in Madhya Pradesh: Sources, Drivers, and Policy Lessons (PDF) (Report). ICRIER. p. 9. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

Figure 8: State-wise Agriculture Growth Rate (2005–06 to 2014–15)

- Mahadevan, Renuka (December 2003). "Productivity growth in Indian agriculture: The role of globalization and economic reform". Asia-Pacific Development Journal. 10 (2): 57–72. doi:10.18356/5728288b-en. S2CID 13201950.

- "Rapid growth of select Asian economies" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2006.

- "India: Priorities for Agriculture and Rural Development". World Bank.

- Biello, David (11 November 2009). "Is Northwestern India's Breadbasket Running Out of Water?". Scientificamerican.com. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Chauhan, Chetan (1 April 2014). "UN climate panel warns India of severe food, water shortage". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2004". 2004. Archived from the original (XLS) on 10 April 2009.

- Sankaran, S. "28". Indian Economy: Problems, Policies and Development. pp. 492–493.

- "Satellites Unlock Secret To Northern India's Vanishing Water". Sciencedaily.com. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Columbia Conference on Water Security in India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Pearce, Fred (1 November 2004). Keepers of the spring: reclaiming our water in an age of globalisation, By Fred Pearce, p. 77. ISBN 9781597268936. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Zakaria, Fareed. "Zakaria: Is India the broken BRIC?" CNN, 21 December 2011.

- National Crime Reports Bureau, ADSI Report Annual – 2012 Archived 10 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine Government of India, p. 242, Table 2.11

- Nagraj, K. (2008). "Farmers suicide in India: magnitudes, trends and spatial patterns" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2011.

- Gruère, G. & Sengupta, D. (2011), Bt cotton and farmer suicides in India: an evidence-based assessment, The Journal of Development Studies, 47(2), 316–337

- Schurman, R. (2013), Shadow space: suicides and the predicament of rural India, Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(3), 597–601

- Das, A. (2011), Farmers' suicide in India: implications for public mental health, International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(1), 21–29

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/167792/11/11_chapter%206.pdf

- National Policy for Farmers, 2007 Archived 24 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- The Telegraph. 23 July 2007 ‘Prohibiting the use of agricultural land for industries is ultimately self-defeating’

- Agriculture marketing india.gov Retrieved in February 2008

- Objectives Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Indian agricultural research institute, Retrieved in December 2007

- "Farmers Commission". Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- " Drought fears loom in India as monsoon stalls." al Jazeera, 5 August 2012.

- "PM Modi: Target to double farmers' income by 2022", The Indian Express, 28 February 2016

- "Tech in Asia – Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". www.techinasia.com. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

Further reading

- Agarwal, Ankit (2011), "Theory of Optimum Utilisation of Resources in agriculture during the Gupta Period", History Today 12, New Delhi, ISSN 2249-748X.

- Akhilesh, K. B., and Kavitha Sooda. "A Study on Impact of Technology Intervention in the Field of Agriculture in India." in Smart Technologies (Springer, Singapore, 2020) pp. 373–385.

- Bhagowalia, Priya, S. Kadiyala, and D. Headey. "Agriculture, income and nutrition linkages in India: Insights from a nationally representative survey." (2012). online

- Bhan, Suraj, and U. K. Behera. "Conservation agriculture in India–Problems, prospects and policy issues." International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2.4 (2014): 1-12.

- Bharti, N. (2018), "Evolution of agriculture finance in India: a historical perspective", Agricultural Finance Review, Vol. 78 No. 3, pp. 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-05-2017-0035

- Brink, Lars. "Support to Agriculture in India in 1995-2013 and the Rules of the WTO." International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium (IATRC) Working Paper 14-01 (2014) online.

- Brown, Trent. Farmers, Subalterns, and activists: social politics of sustainable agriculture in India (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Chauhan, Bhagirath Singh, et al. "Global warming and its possible impact on agriculture in India." in Advances in agronomy (Academic Press, 2014) pp. 65–121.online

- Chengappa, P. G. "Presidential Address: Secondary Agriculture: A Driver for Growth of Primary Agriculture in India." Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 68.902-2016-66819 (2013): 1-19. online

- Dev, S. Mahendra, Srijit Mishra, and Vijay Laxmi Pandey. "Agriculture in India: Performance, Challenges, and Opportunities." in A Concise Handbook of the Indian Economy in the 21st Century (Oxford University Press, 2014) pp. 321–350.

- Goyal, S. & Prabha, & Rai, Dr & Singh, Shree Ram. Indian Agriculture and Farmers-Problems and Reforms. (2016)

- Kekane Maruti Arjun. "Indian, Agriculture- Status, Importance and Role in Indian Economy," International Journal of Agriculture and Food Science Technology, ISSN 2249-3050, Volume 4, Number 4 (2013), pp. 343–346.

- Kumar, Anjani, Krishna M. Singh, and Shradhajali Sinha. "Institutional credit to agriculture sector in India: Status, performance and determinants." Agricultural Economics Research Review 23.2 (2010): 253-264 online.

- Manida, Mr M., and G. Nedumaran. "Agriculture In India: Information About Indian Agriculture & Its Importance." Aegaeum Journal, 8#3 (2020) online

- Mathur, Archana S., Surajit Das, and Subhalakshmi Sircar. "Status of agriculture in India: trends and prospects." Economic and political weekly (2006): 5327-5336 online.

- Nedumaran, Dr G. "E-Agriculture and Rural Development in India." (2020). online

- Ramakumar, R. "Large‐scale Investments in Agriculture in India." IDS Bulletin 43 (2012): 92-103. online

- Ramakumar, R. "Agriculture and the Covid-19 Pandemic: An Analysis with Special Reference to India." Review of Agrarian Studies 10.2369-2020-1856 (2020) online.

- Saradhi, Byra Pardha, et al. "Significant Trends in the Digital Transformation of Agriculture in India." International Journal of Grid and Distributed Computing 13.1 (2020): 2703-2709 [ https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Byra_Pardha_Saradhi2/publication/343760731_Significant_Trends_in_the_Digital_Transformation_of_Agriculture_in_India/links/5f3e25c9a6fdcccc43d7c35d/Significant-Trends-in-the-Digital-Transformation-of-Agriculture-in-India.pdfonline].

- Sharma, Shalendra D. (1999), Development and Democracy in India, Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 125–, ISBN 978-1-55587-810-8

- State of Indian Agriculture 2011–12. New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, March 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Agriculture in India. |

- Indian Agriculture. U.S. Library of Congress.

- Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture & Cooperation website

- Indian Council for Agricultural Research Home Page.

- Principal crops of India and problems with Indian agriculture A collection of statistics (from India Statistical Report, 2011) along with sections of this Wikipedia article and YouTube videos.

- Brighter Green Policy Paper: Veg or NonVeg, India at a Crossroads A December 2011 policy paper analysing the forces behind the rising consumption and production of meat, eggs, and dairy products in India, and the effects on India's people, environment, animals, and the global climate.

- Mukherji, Biman (28 October 2013). "India's farmers start to mechanize amid a labor shortage, increasing productivity. - WSJ.com". Wall Street Journal. Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 30 October 2013.