African-American LGBT community

The African-American LGBT community is part of the overall LGBT culture and overall African-American culture. LGBT (also seen as LGBTQ) stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer. The LGBT community did not receive societal recognition until the historical marking of the Stonewall Riots in 1969 in New York at Stonewall Inn. The Stonewall riots brought domestic and global attention to the lesbian and gay community. Proceeding Stonewall, Romer v. Evans vastly impacted the trajectory of the LGBT community. Ruling in favor of Romer, Justice Kennedy asserted in the case commentary that Colorado's state constitutional amendment "bore no purpose other than to burden LGB persons".[1]

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

|

Advancements in public policy, social discourse, and public knowledge have assisted in the progression and coming out of many LGBT individuals. Statistics show an increase in accepting attitudes towards lesbians and gays among general society. A Gallup survey shows that acceptance rates went from 38% in 1992 to 52% in 2001.[2] However, when looking at the LGBT community through a racial lens, the Black community lacks many of these advantages.[3]

Research and studies are limited for the Black LGBT community due to resistance towards coming out, as well as a lack of responses in surveys and research studies. The coming out rate of blacks is less than those of European (white) descent. The Black LGBT community refers to the African-American (Black) population who identify as LGBT, as a community of marginalized individuals who are further marginalized within their own community. Surveys and research have shown that 80% of African Americans say gays and lesbians endure discrimination compared to the 61% of whites. Black members of the community are not only seen as "other" due to their race, but also due to their sexuality, so they always had to combat racism and homophobia.[3]

History

Pre-Stonewall riot

Trans-woman Lucy Hicks Anderson, born Tobias Lawson in 1886 in Waddy, Kentucky, lived her life serving as a domestic worker in her teen years, eventually becoming a socialite and madame in Oxnard, California during the 1920s and 1930s. In 1945, she was tried in Ventura County for perjury and fraud for receiving spousal allotments from the military, as her dressing and presenting as a woman was considered masquerading. She lost this case but avoided a lengthy jail sentence, only to be tried again by the federal government shortly thereafter. She too lost this case, but she and her husband were sentenced to jail time. After serving their sentences, Lucy and her then husband, Ruben Anderson, relocated to Los Angeles, where they lived quietly until her death in 1954.[4]

Harlem Renaissance

During the Harlem Renaissance, a subculture of LGBTQ African-American artists and entertainers emerged, including people like Alain Locke, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Wallace Thurman, Richard Bruce Nugent, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Moms Mabley, Mabel Hampton, Alberta Hunter, and Gladys Bentley. Places like Savoy Ballroom and the Rockland Palace hosted drag-ball extravaganzas with prizes awarded for the best costumes. Langston Hughes depicted the balls as "spectacles of color". George Chauncey, author of Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940, wrote that during this period "perhaps nowhere were more men willing to venture out in public in drag than in Harlem".[5]

During the first night of the Stonewall riots, LGBTQ African Americans and Latinos likely were the largest percentage of the protestors, because those groups heavily frequented the bar. Homeless black and Latino LGBTQ youth and young adults who slept in nearby Christopher Park were likely among the protestors as well.[5]

Post-Stonewall riot

In 1979, the Lambda Student Alliance (LSA) was established at Howard University. It was the first openly black LGBT organization on a college campus.[6][7]

.jpg.webp)

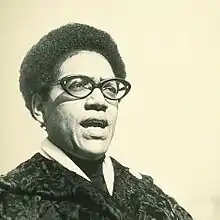

In 1983, after a battle over LGB participation in the 20th anniversary March on Washington, a group of African-American leaders endorsed a national gay rights bill and put Audre Lorde from the National Coalition of Black Gays as speaker on the agenda. In 1984, Rev. Jesse Jackson included LGB people as part of his Rainbow/PUSH.[8]

In 1993, Dr. William F. Gibson, national Chairman of the Board of NAACP, endorsed the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation and repealed the ban on LGB service in the military.[9]

On May 19, 2012, the NAACP passed a resolution in support of same-sex marriage.[10] That same month and year, President Obama became the first sitting president to openly support same-sex marriage.[11]

In 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement was established by three black women, two of whom identify as queer. From its inception, the founders of Black Lives Matter have always put black LGBT voices at the center of the conversation.[12]

In 2017, Moonlight which is a black queer centric film, won several highly acclaimed awards.[13]

In 2018, the critically acclaimed TV show Pose premiered, which is the first to feature a predominately people of color LGBT cast on a mainstream channel.

In 2019, Atlanta's mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms became the first elected official to establish and host an annual event recognizing and celebrating the black LGBT community.[14] Also in 2019, Spelman College which is part of the Atlanta University Center, became the first historically black college or university to fund a chair in queer studies. The endowed chair is named after civil rights activist and famed poet Audre Lorde and backed by a matching gift of $2 million from philanthropist Jon Stryker.[15]And also in 2019, Chicago's mayor Lori Lightfoot became the first openly queer black person elected to lead a major city.

In 2020, Ritchie Torres and Mondaire Jones became the first openly queer black members of the United States Congress.[16]

Some first African-American LGBT holders of political offices in the United States

Rhode Island

- Gordon Fox (D)

- 1st gay African-American member of the Rhode Island General Assembly

- 1st gay African-American Speaker of the Rhode Island House of Representatives

- 1st gay African-American member of the Rhode Island House of Representatives from the 4th and 5th district

Georgia

- Rashad Taylor (D)

- 1st gay African-American member of the Georgia General Assembly

- 1st gay African-American member of the Georgia House of Representatives from the 55th district

Massachusetts

- Althea Garrison (R)

- 1st transgender woman African American member of the Massachusetts General Court

- 1st transgender woman African American of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from the 5th Suffolk District

Nevada

- Pat Spearman (D)

- 1st lesbian African American member of the Nevada Legislature and 1st lesbian African American member of the Nevada Senate from the 1st district

North Carolina

- Marcus Brandon (D)

- 1st gay African-American member of the North Carolina General Assembly and 1st gay African-American member of the North Carolina House of Representatives from the 60th district

Texas

- Barbara Jordan

- 1st African American woman to serve in the Texas House of Representatives (1966)

California

- Ron Oden (D)

- 1st gay African-American United States mayor and 1st gay African American mayor of Palm Springs, California

New Jersey

- Bruce Harris (R)

- 1st gay African-American mayor of Chatham Borough, New Jersey

New York

- Keith St. John (D)

Federal

- Darrin P. Gayles (D)

- 1st gay African-American male United States federal judge

- 1st gay African-American United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida

Economic disparities

The current federal law, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, prohibits employment discrimination. The federal law specifies no discrimination because of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, or genetic information. The current federal law does not specify sexual orientation. There is legislation currently being proposed to congress known as the ENDA (Employment Non-Discrimination Act) that would include hindering discrimination based on sexual orientation, too. And most recently, the Equality Act. However, current policies do not protect sexual orientation and affect the employment rates as well as LGBT individual's incomes and overall economic status. The alone Black people in the United States of America as of the 2010 consensus is 14,129,983 people.[17] Out of that, it is estimated that 4.60 percent of the black population identify as LGBT.

Within the Black LGBT community many face economic disparities and discrimination. Statistically black LGBT individuals are more likely to be unemployed than their non-black counterparts. According to the Williams Institute, the vast difference lies in the survey responses of “not in workforce” from different populations geographically. Black LGBT individuals, nonetheless, face the dilemma of marginalization in the job market. As of 2013, same-sex couples' income is lower than those in heterosexual relationships with an average of $25,000 income. For opposite-sex couples, statistics show a $1,700 increase. Analyzing economic disparities on an intersectional level (gender and race), the black man is likely to receive a higher income than a woman. For men, statistics shows approximately a $3,000 increase from the average income for all black LGBT identified individuals, and a $6,000 increase in salary for same-sex male couples. Female same-sex couples receive $3,000 less than the average income for all black LGBT individuals and approximately $6,000 less than their male counterparts. (Look at Charts below) The income disparity amongst black LGBT families affects the lives of their dependents, contributing to poverty rates. Children growing up in low-income households are more likely to remain in the poverty cycle. Due to economic disparities in the black LGBT community, 32% of children raised by gay black men are in poverty. However, only 13% of children raised by heterosexual black parents are in poverty and only 7% for white heterosexual parents.

Median Incomes for African American Individuals

Median Incomes for African American Individuals

Chart of unemployment percentages of couples and single African American individuals.

Chart of unemployment percentages of couples and single African American individuals.

African Americans and Same-Sex Couples

African Americans and Same-Sex Couples

African Americans and Same-Sex Couples

African Americans and Same-Sex Couples

Chart of unemployment percentages of couples and single African American individuals.

Chart of unemployment percentages of couples and single African American individuals.

Comparatively looking at gender, race, and sexual orientation, black women same-sex couples are likely to face more economic disparities than black women in an opposite sex relationship. Black women in same-sex couples earn $42,000 compared to black women in opposite-sex relationships who earn $51,000, a twenty-one percent increase in income. Economically, black women same-sex couples are also less likely to be able to afford housing. Approximately fifty percent of black women same-sex couples can afford to buy housing compared to white women same-sex couples who have a seventy-two percent rate in home ownership.[19]

Black transgender people

Black transgender individuals face higher rates of discrimination than black LGB individuals. While policies have been implemented to inhibit discrimination based on gender identity, transgender individuals of color lack legal support. Transgender individuals are still not supported by legislation and policies like the LGBT community. New reports show vast discrimination in the black transgender community. Reports show in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey that black transgender individuals, along with non-conforming individuals, have high rates of poverty. Statistics shows a 34% rate of households receiving an income less than $10,000 a year. According to the data, that is twice the rate when looking at transgender individuals of all races and four times higher than the general black population. Many face poverty due to discrimination and bias when trying to purchase a home or apartment. 38% of black trans individuals report in the Discrimination Survey being turned down property due to their gender identity. 31% of the black individuals were evicted due to their identity.[20]

Black transgender individuals also face disparities in education, employment, and health. In education, black transgender and non-conforming persons face brutish environments while attending school. Reporting rates show 49% of black transgender individuals being harassed from kindergarten to twelfth grade. Physical assault rates are at 27% percent, and sexual assault is at 15%. These drastically high rates have an effect on the mental health of black transgender individuals. As a result of high assault/harassment and discrimination, suicide rates are at the same rate (49%) as harassment to black transgender individuals. Employment discrimination rates are similarly higher. Statistics show a 26% rate of unemployed black transgender and non-conforming persons. Many black trans people have lost their jobs or have been denied jobs due to gender identity: 32% are unemployed, and 48% were denied jobs.[20]

Black lesbian culture and identity

Black lesbian identity

There has historically been a lot of racism and racial segregation in lesbian spaces.[21] Racial and class divisions sometimes made it difficult for black and white women to see themselves as on the same side in the feminist movement.[22] Black women faced misogyny from within the black community even during the fight for black liberation. Homophobia was also pervasive in the black community during the Black Arts Movement because “feminine” homosexuality was seen as undermining black power.[23] Black lesbians especially struggled with the stigma they faced within their own community.[22] With unique experiences and often very different struggles, black lesbians have developed an identity that is more than the sum of its parts – black, lesbian, and woman.[24] Some individuals may rank their identities separately, seeing themselves as black first, woman second, lesbian third, or some other permutation of the three; others see their identities as inextricably interwoven.

Gender roles and presentation

The gender relations perspective is a sociological theory which proposes that gender is not just a state of being but rather a system of behavior created through interactions with others, generally to fill various necessary social roles.[25] Same-sex-attracted individuals are just as impacted by the societally reinforced need for these ‘gendered’ roles as heterosexuals are. Within black lesbian communities, gender presentation is often used to indicate the role an individual can be expected to take in a relationship, though many may also simply prefer the presentation for its own sake, assigning less significance to its association with certain behaviors or traits. According to sociologist Mignon Moore, because black lesbians generally existed “outside” of the predominantly white feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s, the community was less affected by the non-black lesbian community’s increased emphasis on androgyne as a rejection of “heterosexual” gender norms.[26]

Instead, they adapted the existing butch/femme dichotomy to form three main categories:

- The terms stud or aggressive (AG) was used to refer to more masculine-presenting lesbians. Stud fashion is generally more in-line with trends popular among black men, rather than the styles typical to non-black butches.

- Individuals now commonly called stems – whom Moore referred to as “gender blenders” – differed from androgynous lesbians by combining aspects of both masculinity and femininity instead of de-emphasizing them.

- Black fems were generally more consistent with white femmes in their feminine expression, though in the modern day, their styles also often align more with the fashion of other black women.

Health disparities

Black LGBT individuals face many health risks due to discriminatory policies and behaviors in medicine. Due to lack of medical coverage and adequate medical treatment, many are faced with heath risks. There is no current legislation fully protecting LGBT individuals from discrimination in the public sphere concerning health care. President Barack Obama has recently written a memo to the Department of Health and Human Services to enact regulations on discrimination of gay and transgender individuals receiving Medicare and Medicaid, as well as to permit full hospital visitation rights to same-sex couples and their families. The United States of Housing and Urban Development proposed policies that would allow access and eligibility to core programs regardless of sexual orientation and gender identity.[27] The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is currently working to be inclusive, as courts have recently passed interpretation of the ACA to prohibit discrimination against transgender individuals and gender non-conforming persons.

HIV/AIDS

One of the greatest concerns in the Black LGBT community is sexually transmitted diseases, and one of the greatest STDs affecting the Black community is HIV/AIDS. Black people account for 44% of new HIV infections in both adults and adolescents. Black women account for 29% of new HIV infections. For black LGBT male-identified individuals, 70% of the population accounts for new HIV infections for both adults and adolescents. The rates of HIV for black LGBT men are higher than their non-black counterparts.[28] One of the major factors that contributes to higher rates of STDs like HIV/AIDS is lack of medical access. Rather than a high prevalence of unsafe sex, it is caused by a limited supply of antiretroviral therapy in non-white communities.[29]

Depiction in popular culture

African-American LGBT culture has been depicted in films such as Patrick Ian Polk's Noah's Arc and Punks, Pariah, and Barry Jenkins' Moonlight, which not only has the main character as a gay African-American but is written by an African American and is based on a play by black gay playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney.[30]

In 2018, the critically acclaimed TV show Pose premiered, which is the first to feature a predominately people of color LGBT cast on a mainstream channel.

Organizations

[31] See also: Category: African-American LGBT organizations

| Name | Years active | Founder | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adodi, Inc. | 1986-Present | Clifford Rawlins | National |

| At the Beach LA | 1988- | Los Angeles | |

| Black AIDS Institute | 1999- | Phill Wilson | National |

| Black Gay Men United | 1987- | Oakland | |

| Black Gay Stuck at Home | 2020-Present | National | |

| Black Men's Xchange | 1989-Present | Cleo Manago | National |

| Brother to Brother | 1982- | San Francisco | |

| Center for Black Equity | 1999-Present | National | |

| Combahee River Collective | 1974-1980 | Boston | |

| Committee of Black Gay Men | 1979- | National | |

| Counter Narrative Project (CNP) | Charles Stephens | Atlanta | |

| D.C. Black Pride | 1991-Present | Washington, DC | |

| Dallas Black Pride | 1996-Present | Dallas | |

| Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD) | 1986-Present | Reverend Charles Angel | New York |

| Hispanic Black Gay Coalition | 2009- | Boston | |

| Hotter than July | 1996-Present | Detroit | |

| LGBT Detroit | 2003-Present | Curtis Lipscomb | Detroit |

| Lighthouse Foundation | 2019-Present | Lighthouse Church of Chicago UCC | Chicago |

| Men of All Colors Together | 1980-1999 | Boston | |

| Men of Melanin Magic | 2016-Present | Boston | |

| Mobilizing Our Brothers Initiative (MOBI) | New York | ||

| National Association of Black and White Men Together | 1980- | National | |

| National Black Justice Coalition | 2003-Present | National | |

| National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays | 1978-1990 | A. Billy S. Jones, Darlene Garner, & Delores P. Berry | National |

| Native Son | 2016-Present | Emil Wilbekin | New York |

| The Okra Project | 2018-Present | Ianne Fields Stewart | New York |

| People of Color in Crisis (POCC) | 1989-2008 | Brooklyn | |

| Pomo Afro Homo | 1990-1995 | Djola Bernard Branner, Brian Freeman, Eric Gupton, & Marvin K. White | San Francisco |

| The Portal (Community Center) | 2001- | Rickie Green | Baltimore |

| Salsa Soul Sisters | 1971 | New York | |

| Unity, Incorporated | 1989- | Tyrone Smith & James Roberts | Philadelphia |

| Us Helping Us, People into Living, Inc. | 1985- | Rainey Cheeks | Washington, DC |

Black gay pride

Several major cities across the nation host black gay pride events focused on uplifting and celebrating the black LGBT community and culture. The two largest are Atlanta Black Pride and D.C. Black Pride.

Some notable people

.jpg.webp)

- Jonathan Capehart

- DeRay McKesson

- Tevin Campbell

- Taylor Bennett

- E. Lynn Harris

- Bayard Rustin

- Glenn Burke

- Johnny Mathis

- Keith Boykin

- Darrin P. Gayles

- Countee Cullen

- Ryan Jamaal Swain

- Ritchie Torres

- Langston Hughes

- Wilson Cruz

- Alvin Ailey

- Larry Levan

- Frankie Knuckles

- Tony Humphries

- Billy Porter

- Karamo Brown

- Mel Tomlinson

- Clark Moore

- Jason Collins

- Michael Sam

- Jussie Smollett

- iLoveMakonnen

- John Ameachi

- James Baldwin

- Paris Barclay

- Charles M. Blow

- Jericho Brown

- Lee Daniels

- Terrance Dean

- Anye Elite

- Willi Smith

- Michael Arceneaux

- David Hampton

- Marcellas Reynolds

- Ryan Russell

- LZ Granderson

- Essex Hemphill

- Langston Hughes

- Don Lemon

- Darryl Stephens

- Bruce Nugent

- Saeed Jones

- Tarell Alvin Mccraney

- Patrick Ian Polk

- Alain LeRoy Locke

- Frank Ocean

- Marlon Riggs

- Shaun T

- Harrison David Rivers

- RuPaul

- Justin Simien

- Andrew Gillum

- Joshua Johnson

- Daryl Stephens

- Sylvester

- Andrew Leon Talley

- Tyler The Creator

- Lil Nas X

- Wentworth Miller

Lesbian and bisexual women

- Niecy Nash

- Deborah Batts

- Lori Lightfoot

- Amandla Stenberg

- Tessa Thompson

- Barbara Jordan

- Willow Smith

- Raven-Symoné

- Tyra Bolling

- Cardi B[32]

- Brittney Griner

- Seimone Augustus

- Angel McCoughtry

- Samira Wiley

- Young M.A.

- Robin Roberts

- Barbara Jordan

- E. Denise Simmons

- Da Brat

- Karine Jean-Pierre

- Josephine Baker

- Octavia Butler

- Gladys Bentley

- Angela Davis

- Rosario Dawson

- Lorraine Hansberry

- Mabel Hampton

- Audre Lorde

- Meshell Ndegeocello

- Ma Rainey

- Moms Mabley

- Wanda Sykes

- Lena Waithe

- Rebecca Walker

- Nell Carter

- Ethel Waters

- Alice Walker

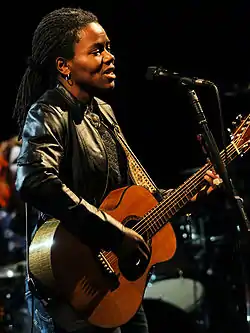

- Tracy Chapman

- Mimi Faust

- Bessie Smith

Pansexual

Transgender

Gender non-conforming

See also

References

- "Movement Analysis: The Pathway to Victory, A Review of Supreme Court LGBT Cases" (PDF). National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Newport, Frank. "American Attitudes Toward Homosexuality Continue to Become More Tolerant". Gallup. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Gecewicz, Claire (October 7, 2014). "Blacks are Lukewarm to Gay Marriage, but Most Say Businesses Most Provide Wedding Services to Gay Couples". Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- Riley, Snorton C. Black on both sides: a racial history of trans identity. Minneapolis. ISBN 9781452955865. OCLC 1008757426.

- Dis-membering Stonewall

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1980/04/24/gays-coming-out-on-campus-first-black-group-at-howard/22ba5e77-4bf3-4653-b5d2-dc98f3093adb/

- https://www.blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/meet-chi-hughes-the-activist-who-co-founded-the-first-openly-lgbtq-student-organization-at-an-hbcu

- Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, Volume 1

- NAACP’s Long History on LGBT Equality

- NAACP endorses same-sex marriage, says it's a civil right

- https://www.cnn.com/2012/05/09/politics/obama-same-sex-marriage/index.html

- https://abcnews.go.com/US/start-black-lives-matter-lgbtq-lives/story?id=71320450

- https://qz.com/919985/oscars-2017-moonlight-wins-best-picture-and-sends-a-powerful-message-about-black-cinema/

- https://thegavoice.com/community/mayor-bottoms-hosts-inaugural-black-gay-pride-reception/

- https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/spelman-first-historically-black-college-create-chair-queer-studies-n1074011

- https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/addybaird/ritchie-torres-mondaire-jones-first-gay-black-congress

- "Households and Families: 2010" (PDF). CB. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- "LGBT Families of Color: Facts at a Glance" (PDF). National Black Justice Coalition. January 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- Dang, Alain; Frazer, Somjen (December 2005). "Black Same-Sex Households in the United States" (PDF). National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute National Black Justice Coalition. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Grant, Jaime; Mottet, Lisa; Tanis, Justin; Harrison, Jack; Herman, Jody; Keisling, Mara (2011). "Injustice at Every Turn" (PDF). National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-06. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Moore, Mignon (2008). "Gendered Power Relations among Women". American Sociological Review. 73 (2): 335–356. doi:10.1177/000312240807300208. S2CID 143591010 – via ProQuest.

- Moore, Mignon R. (2006). "Lipstick or Timberlands? Meanings of Gender Presentation in Black Lesbian Communities". Signs. 32 (1): 113–139. doi:10.1086/505269. JSTOR 10.1086/505269. S2CID 146712513 – via JSTOR.

- Lewis, Cristopher S. (2012). "Cultivating Black Lesbian Shamelessness: Alice Walker's 'The Color Purple'". Rocky Mountain Review. 66 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1353/rmr.2012.0027. JSTOR 41763555. S2CID 145014258 – via JSTOR.

- Bowleg, Lisa (2008). "When Black + Lesbian + Woman [Not Equal To] Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research". Sex Roles. 59 (5–6): 312–325. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z. S2CID 49303030 – via ProQuest.

- Moore, Mignon (2008). "Gendered Power Relations among Women". American Sociological Review. 73 (2): 335–356. doi:10.1177/000312240807300208. S2CID 143591010 – via ProQuest.

- Moore, Mignon R. (2006). "Lipstick or Timberlands? Meanings of Gender Presentation in Black Lesbian Communities". Signs. 32 (1): 113–139. doi:10.1086/505269. JSTOR 10.1086/505269. S2CID 146712513 – via JSTOR.

- Burns, Crosby (July 19, 2011). "Gay and Transgender Discrimination Outside the Workplace". Center for American Progress. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- "HIV Among African Americans" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. February 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- Oster, A.; et al. (2010). "Understanding disparities in HIV infection between black and white men who have sex with men in the United States: data from the national HIV behavioral surveillance system". International Aids Society. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- Gilbert, Sophie. "The Symbolism of Water in Barry Jenkins's 'Moonlight'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2016-12-28.

- Bost, Darius. Evidence of being: the black gay cultural renaissance and the politics of violence. Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-58979-4. OCLC 1028903800.

- https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2018/05/rapper-cardi-b-comes-bisexual/

.jpg.webp)