Tracy Chapman

Tracy Chapman (born March 30, 1964) is an American singer-songwriter, known for her hits "Fast Car" and "Give Me One Reason", along with other singles "Talkin' 'bout a Revolution", "Baby Can I Hold You", "Crossroads", "New Beginning", and "Telling Stories". She is a multi-platinum and four-time Grammy Award–winning artist.[1]

Tracy Chapman | |

|---|---|

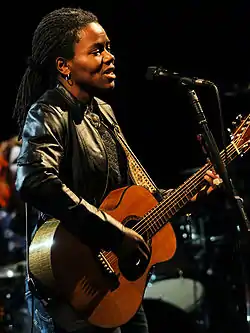

Chapman performing live in Bruges, Belgium in July 2009 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | March 30, 1964 Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Singer-songwriter |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1986–present |

| Labels | Elektra |

| Website | TracyChapman.com |

Chapman was signed to Elektra Records by Bob Krasnow in 1987. The following year she released her critically acclaimed debut album, Tracy Chapman, which became a multi-platinum worldwide hit. The album earned Chapman six Grammy Award nominations, including Album of the Year, three of which she won: Best New Artist, Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for her single "Fast Car", and Best Contemporary Folk Album. Chapman released her second album, Crossroads, the following year, which garnered her an additional Grammy nomination. Since then, Chapman has experienced further success with six more studio albums, which include her multi-platinum fourth album, New Beginning, for which she won a fourth Grammy Award, for Best Rock Song, for its lead single "Give Me One Reason". Chapman's most recent album is Our Bright Future, released in 2008.

Early life

Chapman was born in Cleveland, Ohio. Her parents divorced when she was four years of age.[2] She was raised by her mother, who bought her music-loving three-year-old daughter a ukulele despite having little money.[3] Chapman began playing the guitar and writing songs at age eight. She says that she may have been first inspired to play the guitar by the television show Hee Haw.[4] Chapman's family received welfare. In her native Cleveland, school desegregation efforts led to racial unrest and riots; Chapman experienced frequent bullying and racially motivated assaults as a child.[5]

Raised as a Baptist, Chapman attended an Episcopal high school[4] and was accepted into the program A Better Chance, which sponsors students at college preparatory high schools away from their home community. She graduated from Wooster School in Connecticut, then attended Tufts University,[3][2] graduating with a B.A. degree in Anthropology and African studies.[6]

Career

Chapman made her major-stage debut as an opening act for women's music pioneer Linda Tillery at Boston's Strand Theater on May 3, 1985.[7] Another Tufts student, Brian Koppelman, heard Chapman playing and brought her to the attention of his father, Charles Koppelman. Koppelman, who ran SBK Publishing, signed Chapman in 1986. After Chapman graduated from Tufts in 1987, he helped her to sign a contract with Elektra Records.[6]

At Elektra, she released Tracy Chapman (1988).[2] The album was critically acclaimed,[8] and she began touring and building a fanbase.[2] "Fast Car" began its rise on the U.S. charts soon after she performed it at the televised Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert in June 1988; it became a number 6 pop hit on the Billboard Hot 100 for the week ending August 27, 1988.[9] Rolling Stone ranked the song number 167 on their 2010 list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[10] It is the highest-ranking song on the Rolling Stone list that was both performed and solely written by a female artist. "Talkin' 'bout a Revolution", the follow-up to Fast Car, charted at number 75 and was followed by "Baby Can I Hold You", which peaked at number 48. The album sold well, going multi-platinum and winning three Grammy Awards, including an honor for Chapman as Best New Artist. Later in 1988, Chapman was a featured performer on the worldwide Amnesty International Human Rights Now! Tour.[2]

Chapman's follow-up album, Crossroads (1989), was less commercially successful than her debut had been, but it still achieved platinum status. By 1992's Matters of the Heart, Chapman was playing to a small but devoted audience. Her fourth album, New Beginning (1995), proved successful, selling over three million copies in the U.S. The album included the hit single "Give Me One Reason", which won the 1997 Grammy for Best Rock Song and became Chapman's most successful single to date, peaking at Number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. Following a four-year hiatus, her fifth album, Telling Stories, was released in 2000. Its hit single, "Telling Stories", received heavy airplay on European radio stations and on Adult Alternative and Hot AC stations in the United States. Chapman toured Europe and the United States in 2003 in support of her sixth album, Let It Rain (2002).

To support her seventh studio album, Where You Live (2005), Chapman toured major U.S. cities in October and toured Europe over the remainder of the year. The "Where You Live" tour was extended into 2006; the 28-date European tour featured summer concerts in Germany, Italy, France, Sweden, Finland, Norway, the UK, Russia, and more. On June 5, 2006, she performed at the 5th Gala of Jazz in Lincoln Center, New York, and in a session at the 2007 TED (Technology Entertainment Design) conference in Monterey, California.

Chapman was commissioned by the American Conservatory Theater to compose music for its production of Athol Fugard's Blood Knot, a play on apartheid in South Africa, staged in early 2008.[11]

Atlantic Records released Chapman's eighth studio album, Our Bright Future (2008).[12] Chapman made a 26-date solo tour of Europe. She returned to tour Europe and selected North American cities during the summer of 2009. She was backed by Joe Gore on guitars, Patrick Warren on keyboards, and Dawn Richardson on percussion.[13]

Chapman was appointed a member of the 2014 Sundance Film Festival U.S. Documentary jury.[14]

Chapman performed Ben E. King's "Stand By Me" on one of the final episodes of the Late Show with David Letterman in April 2015. The performance became a viral hit and was the focus of various news articles including some by Billboard and The Huffington Post.[15]

On November 20, 2015, Chapman released Greatest Hits, consisting of 18 tracks including the live version of "Stand by Me", the album is Chapman's first global compilation release.[16]

In October 2018, Chapman sued the rapper Nicki Minaj over copyright infringement, alleging that Minaj had sampled her song "Baby Can I Hold You" without permission.[17] Chapman's lawsuit requested an injunction to prevent Minaj releasing the song "Sorry" and stated that she had "repeatedly denied" permission for "Baby Can I Hold You" to be sampled. Chapman has a policy of declining all such requests, according to the lawsuit. In September 2020, District Court judge Virginia A. Phillips ruled in favor of Minaj, stating that Minaj's experimentation with Chapman's song constitutes fair use rather than copyright infringement.[18] In January 2021, the dispute was completely settled when Minaj paid Chapman $450,000 to avoid a pending trial over how the track had been leaked to radio host Funkmaster Flex, who had played it on his radio show.[19]

Social activism

Chapman is a politically and socially active musician. In a 2009 interview with the American radio network NPR, she said, "I'm approached by lots of organizations and lots of people who want me to support their various charitable efforts in some way. And I look at those requests and I basically try to do what I can. And I have certain interests of my own, generally an interest in human rights."[4] She has performed at numerous socially aware events and continues to do so. In 1988, she performed in London as part of a worldwide concert tour to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with Amnesty International.[20] The same year Chapman also performed in the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute, an event which raised money for South Africa's Anti-Apartheid Movement and seven children's charities.[21] In 2004, Chapman performed (and rode) in the AIDS/LifeCycle event.[22]

Chapman has also been involved with Cleveland's elementary schools. A music video produced by Chapman that highlights significant achievements in African-American history has become an important teaching tool in Cleveland Public Schools. Chapman also agreed to sponsor a "Crossroads in Black History" essay contest for high school students in Cleveland and other cities.[23]

Chapman received an honorary doctorate from Saint Xavier University in Chicago in 1997.[24] In 2004, Chapman was given an honorary doctorate in Fine Arts by her alma mater, Tufts University, recognizing her commitment to social activism.[25]

I'm fortunate that I've been able to do my work and be involved in certain organizations, certain endeavors, and offered some assistance in some way. Whether that is about raising money or helping to raise awareness, just being another body to show some force and conviction for a particular idea. Finding out where the need is – and if someone thinks you're going to be helpful, then helping.

— Tracy Chapman[26]

Chapman often performs at and attends charity events such as Make Poverty History, amfAR, and AIDS/LifeCycle, to support social causes. She identifies as a feminist.[27]

Personal life

Although Chapman has never publicly disclosed her sexual orientation, writer Alice Walker has stated that she and Chapman were in a romantic relationship during the mid-1990s.[28] Chapman maintains a strong separation between her personal and professional life.[29][2] "I have a public life that's my work life and I have my personal life," she said. "In some ways, the decision to keep the two things separate relates to the work I do."[29]

Discography

- Studio albums

- Tracy Chapman (1988)

- Crossroads (1989)

- Matters of the Heart (1992)

- New Beginning (1995)

- Telling Stories (2000)

- Let It Rain (2002)

- Where You Live (2005)

- Our Bright Future (2008)

References

- "Tracy Chapman". Grammy Awards. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Pond, Steve (September 22, 1988). "Tracy Chapman: On Her Own Terms". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Williamson, Nigel (March 11, 2008). "Tracy Chapman's Biography". About-Tracy-Chapman.net. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Martin, Michael (August 20, 2009). "Without Further Ado, Songster Tracy Chapman Returns". NPR. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Fleming, Amy (October 31, 2008). "Amy Fleming on Tracy Chapman, the quiet revolutionary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2020 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Tracy Chapman". All Music Guide. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009 – via Pandora.com.

- McLaughlin, Jeff (May 1, 1985). "Linda Tillery's 'healing music'". Boston Globe. Boston, MA. p. 78.

- Murphy, Peter. "On this day in 1988: Tracy Chapman starts a three-week run at No.1 with her eponymous debut album". Hotpress. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "The Hot 100 Chart". Billboard. August 27, 1988. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- "500 Greatest Songs of All Time: Tracy Chapman, 'Fast Car'". Rolling Stone. April 7, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Jessica Werner Zack (2008). "A Guiding Hopefulness" (PDF). American Conservatory Theater. pp. 28–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "Our Bright Future (2008), Tracy Chapman's 8th album". November 1, 2008. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "2009 – Our Bright Future Summer European + US Tour" Archived August 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, About Tracy Chapman, December 22, 2008.

- "Tracy Chapman, Dana Stevens, Bryan Singer, Max Mayer and More Among 2014 Sundance Film Festival Jurors". Broadway World. January 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Pitney, Nico (June 12, 2015). "Tracy Chapman Singing 'Stand By Me' Will Break Your Heart". HuffPost. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "Tracy Chapman Greatest Hits releases on Nov 20, 2015". About Tracy Chapman. October 16, 2015. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "Tracy Chapman sues Nicki Minaj over unauthorised sample". The Guardian. October 23, 2018. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Maddaus, Gene (September 16, 2020). "Judge Rules in Favor of Nicki Minaj in Tracy Chapman Copyright Dispute". Variety. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- Brodsky, Rachel (January 9, 2021). "Nicki Minaj to pay Tracy Chapman $450k in 'Sorry' copyright infringement lawsuit". The Independent. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- Paul Paz y Miño (January 24, 2014). "An Activist Remembers the Concert That Moved a Generation". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "Live Aid's Legacy of Charity Concerts". BBC News. June 30, 2005. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "AIDS LifeCycle 2004". Online Posting. YouTube. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "School Uses Video To Teach Black History". Curriculum Review. 29 (8): 11. 1990.

- "Previous honorary degree recipients". Saint Xavier University. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "Commencement Speaker Announced". E-News. Tufts University. May 23, 2004. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Younge, Gary (September 28, 2002). "A Militant Mellow". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Amy Fleming (October 31, 2008). "The quiet revolutionary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Wajid, Sara (December 15, 2006). "No retreat". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- "2002 – Tracy Chapman still introspective?" Archived August 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, About Tracy Chapman, October 15, 2002.

External links

- Official website

- Tracy Chapman at AllMusic

- Tracy Chapman discography at Discogs

- Tracy Chapman at Curlie

- Atlantic Records page

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jody Watley |

Grammy Award for Best New Artist 1989 |

Succeeded by Milli Vanilli (Award later revoked) |

| Preceded by Whitney Houston for "I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)" |

Grammy Award for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance 1989 for "Fast Car" |

Succeeded by Bonnie Raitt for "Nick of Time" |

| Preceded by Steve Goodman for Unfinished Business |

Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album 1989 for Tracy Chapman |

Succeeded by Indigo Girls for Indigo Girls |

| Preceded by Glen Ballard and Alanis Morissette for "You Oughta Know" |

Grammy Award for Best Rock Song 1997 for "Give Me One Reason" |

Succeeded by Wallflowers for "One Headlight" |