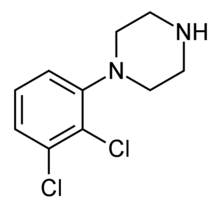

2,3-Dichlorophenylpiperazine

2,3-Dichlorophenylpiperazine (2,3-DCPP or DCPP) is a chemical compound from the phenylpiperazine family. It is both a precursor in the synthesis of aripiprazole and one of its metabolites.[1][2] It is unclear whether 2,3-DCPP is pharmacologically active as a serotonin receptor agonist similar to its close analogue 3-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP), though it has been shown to act as a partial agonist of the dopamine D2 and D3 receptors.[3]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.126.497 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H12Cl2N2 | |

| Molar mass | 231.12 g/mol |

| Appearance | brown oil |

| Density | 1.272g/cm3 °C |

| Melting point | 242 to 244 °C (468 to 471 °F; 515 to 517 K) |

| Boiling point | 365.1 °C (689.2 °F; 638.2 K) at 760mmHg |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 174.6 °C (346.3 °F; 447.8 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Legality

2,3-DCPP has been made illegal in Japan and Hungary after having been identified in seized designer drug samples.[4][5]

Analogues and derivatives

As with the related compound mCPP, 2,3-DCPP is an essential precursor to several pharmaceutical drugs which are widely used in medicine, and is also formed as a metabolite of these drugs in patients, although generally only in insignificant amounts.

The positional isomer 3,4-dichlorophenylpiperazine (3,4-DCPP) is also known, and acts as both a serotonin releaser via the serotonin transporter,[6] and a β1-adrenergic receptor blocker,[7] though with relatively low affinity at both targets.

See also

References

- Leś A, Badowska-Rosłonek K, Łaszcz M, Kamieńska-Duda A, Baran P, Kaczmarek Ł (2010). "Optimization of aripiprazole synthesis". Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica. 67 (2): 151–7. PMID 20369792.

- Caccia S (August 2007). "N-dealkylation of arylpiperazine derivatives: disposition and metabolism of the 1-aryl-piperazines formed". Current Drug Metabolism. 8 (6): 612–22. doi:10.2174/138920007781368908. PMID 17691920.

- Newman AH, Beuming T, Banala AK, Donthamsetti P, Pongetti K, LaBounty A, et al. (August 2012). "Molecular determinants of selectivity and efficacy at the dopamine D3 receptor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 55 (15): 6689–99. doi:10.1021/jm300482h. PMC 3415572. PMID 22632094.

- "指定薬物名称・構造式一覧(平成27年9月16日現在)" (PDF) (in Japanese). 厚生労働省. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- A Magyarországon megjelent, a Kábítószer és Kábítószer-függőség Európai Megfigyelő Központjának Korai Jelzőrendszerébe (EMCDDA EWS) 2005 óta bejelentett ellenőrzött anyagok büntetőjogi vonatkozású besorolása

- Walline CC, Nichols DE, Carroll FI, Barker EL (June 2008). "Comparative molecular field analysis using selectivity fields reveals residues in the third transmembrane helix of the serotonin transporter associated with substrate and antagonist recognition". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 325 (3): 791–800. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.136200. PMC 2637348. PMID 18354055.

- Christopher JA, Brown J, Doré AS, Errey JC, Koglin M, Marshall FH, et al. (May 2013). "Biophysical fragment screening of the β1-adrenergic receptor: identification of high affinity arylpiperazine leads using structure-based drug design". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 56 (9): 3446–55. doi:10.1021/jm400140q. PMC 3654563. PMID 23517028.

External links

Media related to 2,3-Dichlorophenylpiperazines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 2,3-Dichlorophenylpiperazines at Wikimedia Commons