Olanzapine

Olanzapine, sold under the trade name Zyprexa among others, is an atypical antipsychotic primarily used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[7] For schizophrenia, it can be used for both new-onset disease and long-term maintenance.[7] It is taken by mouth or by injection into a muscle.[7]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zyprexa, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601213 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Atypical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60-65%[2][3][4] |

| Protein binding | 93%[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver (direct glucuronidation and CYP1A2 mediated oxidation) |

| Elimination half-life | 33 hours, 51.8 hours (elderly)[5] |

| Excretion | Urine (57%; 7% as unchanged drug), faeces (30%)[5][6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.320 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

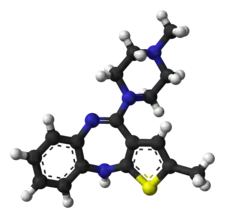

| Formula | C17H20N4S |

| Molar mass | 312.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 195 °C (383 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Practically insoluble in water mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include weight gain, movement disorders, dizziness, feeling tired, constipation, and dry mouth.[7] Other side effects include low blood pressure with standing, allergic reactions, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, high blood sugar, seizures, gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, and tardive dyskinesia.[7] In older people with dementia, its use increases the risk of death.[7] Use in the later part of pregnancy may result in a movement disorder in the baby for some time after birth.[7] Although how it works is not entirely clear, it blocks dopamine and serotonin receptors.[7]

Olanzapine was patented in 1971 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1996.[7][8] It is available as a generic medication.[7] In 2017, it was the 239th-most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses

Schizophrenia

The first-line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication, with olanzapine being one such medication.[11] Olanzapine appears to be effective in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, treating acute exacerbations, and treating early-onset schizophrenia.[12][13][14][15] The usefulness of maintenance therapy, however, is difficult to determine, as more than half of people in trials quit before the 6-week completion date.[16] Treatment with olanzapine (like clozapine) may result in increased weight gain and increased glucose and cholesterol levels when compared to most other second-generation antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia.[13][17]

Comparison

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the British Association for Psychopharmacology, and the World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry suggest that little difference in effectiveness is seen between antipsychotics in prevention of relapse, and recommend that the specific choice of antipsychotic be chosen based on a person's preference and the drug's side-effect profile.[18][19][20] The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality concludes that olanzapine is not different from haloperidol in the treatment of positive symptoms and general psychopathology, or in overall assessment, but that it is superior for the treatment of negative and depressive symptoms.[21] It has a lower risk of causing movement disorders than typical antipsychotics.[12]

In a 2013 comparison of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia, olanzapine was ranked third in efficacy. It was 5% more effective than risperidone (fourth), 24-27% more effective than haloperidol, quetiapine, and aripiprazole, and 33% less effective than clozapine (first).[12] A 2013 review of first-episode schizophrenia concluded that olanzapine is superior to haloperidol in providing a lower discontinuation rate, and in short-term symptom reduction, response rate, negative symptoms, depression, cognitive function, discontinuation due to poor efficacy, and long-term relapse, but not in positive symptoms or on the clinical global impressions (CGI) score. In contrast, pooled second-generation antipsychotics showed superiority to first-generation antipsychotics only against the discontinuation, negative symptoms (with a much larger effect seen among industry- compared to government-sponsored studies), and cognition scores. Olanzapine caused less extrapyramidal side effects and less akathisia, but caused significantly more weight gain, serum cholesterol increase, and triglyceride increase than haloperidol.[22]

A 2012 review concluded that among 10 atypical antipsychotics, only clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone were better than first-generation antipsychotics.[23] A 2011 review concluded that neither first- nor second-generation antipsychotics produce clinically meaningful changes in CGI scores, but found that olanzapine and amisulpride produce larger effects on the PANSS and BPRS batteries than five other second-generation antipsychotics or pooled first-generation antipsychotics.[24] A 2010 Cochrane systematic review found that olanzapine may have a slight advantage in effectiveness when compared to aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone.[17] No differences in effectiveness were detected when comparing olanzapine to amisulpride and clozapine.[17] A 2014 meta-analysis of 9 published trials having minimum duration 6 months and median duration 52 weeks concluded that olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone had better effects on cognitive function than amisulpride and haloperidol.[25]

Bipolar disorder

Olanzapine is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as a first-line therapy for the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder.[26] Other recommended first-line treatments are haloperidol, quetiapine, and risperidone.[26] It is recommended in combination with fluoxetine as a first-line therapy for acute bipolar depression, and as a second-line treatment by itself for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.[26]

The Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommends olanzapine as a first-line maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder and the combination of olanzapine with fluoxetine as second-line treatment for bipolar depression.[27]

A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that olanzapine with fluoxetine was the most effective among 9 treatments for bipolar depression included in the analysis.[28]

Other uses

Evidence does not support the use of atypical antipsychotics, including olanzapine, in eating disorders.[29]

Olanzapine has not been rigorously evaluated in generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, delusional parasitosis, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Olanzapine is no less effective than lithium or valproate and more effective than placebo in treating bipolar disorder.[30] It has also been used for Tourette syndrome and stuttering.[31]

Olanzapine has been studied for the treatment of hyperactivity, aggressive behavior, and repetitive behaviors in autism.[32]

Olanzapine is frequently prescribed off-label for the treatment of insomnia, including difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. The daytime sedation experienced with olanzapine is generally comparable to quetiapine and lurasidone, which is a frequent complaint in clinical trials. In some cases, the sedation due to olanzapine impaired the ability of people to wake up at a consistent time every day. Some evidence of efficacy for treating insomnia is seen, but long-term studies (especially for safety) are still needed.[33]

Olanzapine has been recommended to be used in antiemetic regimens in people receiving chemotherapy that has a high risk for vomiting.[34]

Pregnancy and lactation

Olanzapine is associated with the highest placental exposure of any atypical antipsychotic.[35] Despite this, the available evidence suggests it is safe during pregnancy, although the evidence is insufficiently strong to say anything with a high degree of confidence.[35] Olanzapine is associated with weight gain, which according to recent studies, may put olanzapine-treated patients' offspring at a heightened risk for neural tube defects (e.g. spina bifida).[36][37] Breastfeeding in women taking olanzapine is advised against because olanzapine is secreted in breast milk, with one study finding that the exposure to the infant is about 1.8% that of the mother.[5]

Elderly

Citing an increased risk of stroke, in 2004, the Committee on the Safety of Medicines in the UK issued a warning that olanzapine and risperidone, both atypical antipsychotic medications, should not be given to elderly patients with dementia. In the U.S., olanzapine comes with a black box warning for increased risk of death in elderly patients. It is not approved for use in patients with dementia-related psychosis.[38] A BBC investigation in June 2008, though, found that this advice was being widely ignored by British doctors.[39] Evidence suggested that elderly are more likely to experience weight gain on olanzapine compared to aripiprazole and risperidone.[40]

Adverse effects

The principal side effect of olanzapine is weight gain, which may be profound in some cases and/or associated with derangement in blood-lipid and blood-sugar profiles (see section metabolic effects). A recent meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerance of 15 antipsychotic drugs (APDs) found that it had the highest propensity for causing weight gain out of the 15 APDs compared with an SMD of 0.74[12] Extrapyramidal side effects, although potentially serious, are infrequent to rare from olanzapine,[41] but may include tremors and muscle rigidity.

It is not recommended to be used by IM injection in acute myocardial infarction, bradycardia, recent heart surgery, severe hypotension, sick sinus syndrome, and unstable angina.[42]

Several patient groups are at a heightened risk of side effects from olanzapine and antipsychotics in general. Olanzapine may produce nontrivial high blood sugar in people with diabetes mellitus. Likewise, the elderly are at a greater risk of falls and accidental injury. Young males appear to be at heightened risk of dystonic reactions, although these are relatively rare with olanzapine. Most antipsychotics, including olanzapine, may disrupt the body's natural thermoregulatory systems, thus permitting excursions to dangerous levels when situations (exposure to heat, strenuous exercise) occur.[5][6][43][44][45]

Other side effects include galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, and erectile dysfunction (impotence).[46]

Paradoxical effects

Olanzapine is used therapeutically to treat serious mental illness. Occasionally, it can have the opposite effect and provoke serious paradoxical reactions in a small subgroup of people, causing unusual changes in personality, thoughts, or behavior; hallucinations and excessive thoughts about suicide have also been linked to olanzapine use.[47]

Drug-induced OCD

Many different types of medication can create or induce pure obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in patients who have never had symptoms before. A new chapter about OCD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (2013) now specifically includes drug-induced OCD.

Atypical antipsychotics (second-generation antipsychotics), such as olanzapine (Zyprexa), have been proven to induce de novo OCD in patients.[48][49][50][51]

Metabolic effects

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all atypical antipsychotics to include a warning about the risk of developing hyperglycemia and diabetes, both of which are factors in the metabolic syndrome. These effects may be related to the drugs' ability to induce weight gain, although some reports have been made of metabolic changes in the absence of weight gain.[52][53] Studies have indicated that olanzapine carries a greater risk of causing and exacerbating diabetes than another commonly prescribed atypical antipsychotic, risperidone. Of all the atypical antipsychotics, olanzapine is one of the most likely to induce weight gain based on various measures.[54][55][56][57][58] The effect is dose dependent in humans[59] and animal models of olanzapine-induced metabolic side effects. There are some case reports of olanzapine-induced diabetic ketoacidosis.[60] Olanzapine may decrease insulin sensitivity,[61][62] though one 3-week study seems to refute this.[63] It may also increase triglyceride levels.[55]

Despite weight gain, a large multicenter, randomized National Institute of Mental Health study found that olanzapine was better at controlling symptoms because patients were more likely to remain on olanzapine than the other drugs.[64] One small, open-label, nonrandomized study suggests that taking olanzapine by orally dissolving tablets may induce less weight gain,[65] but this has not been substantiated in a blinded experimental setting.

Post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome

Postinjection delirium/sedation syndrome (PDSS) is a rare syndrome that is specific to the long-acting injectable formulation of olanzapine, olanzapine pamoate.[66] The incidence of PDSS with olanzapine pamoate is estimated to be 0.07% of administrations, and is unique among other second-generation, long-acting antipsychotics (e.g. paliperidone palmitate), which do not appear to carry the same risk.[66] PDSS is characterized by symptoms of delirium (e.g. confusion, difficulty speaking, and uncoordinated movements) and sedation.[66] Most people with PDSS exhibit both delirium and sedation (83%).[66] Although less specific to PDSS, a majority of cases (67%) involved a feeling of general discomfort.[66] PDSS may occur due to accidental injection and absorption of olanzapine pamoate into the bloodstream, where it can act more rapidly, as opposed to slowly distributing out from muscle tissue.[66] Using the proper, intramuscular-injection technique for olanzapine pamoate helps to decrease the risk of PDSS, though it does not eliminate it entirely.[66] This is why the FDA advises that people who are injected with olanzapine pamoate be watched for 3 hours after administration, in the event that PDSS occurs.[66]

Animal toxicology

Olanzapine has demonstrated carcinogenic effects in multiple studies when exposed chronically to female mice and rats, but not male mice and rats. The tumors found were in either the liver or mammary glands of the animals.[67]

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[68] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[69] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[69] Less commonly, vertigo, numbness, or muscle pains may occur.[69] Symptoms generally resolve after a short time.[69]

Tentative evidence indicates that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[70] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[71] Rarely, tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[69]

Overdose

Symptoms of an overdose include tachycardia, agitation, dysarthria, decreased consciousness, and coma. Death has been reported after an acute overdose of 450 mg, but also survival after an acute overdose of 2000 mg.[72] Fatalities generally have occurred with olanzapine plasma concentrations greater than 1000 ng/ml post mortem, with concentrations up to 5200 ng/ml recorded (though this might represent confounding by dead tissue, which may release olanzapine into the blood upon death).[73] No specific antidote for olanzapine overdose is known, and even physicians are recommended to call a certified poison control center for information on the treatment of such a case.[72] Olanzapine is considered moderately toxic in overdose, more toxic than quetiapine, aripiprazole, and the SSRIs, and less toxic than the monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants.[35]

Interactions

Drugs or agents that increase the activity of the enzyme CYP1A2, notably tobacco smoke, may significantly increase hepatic first-pass clearance of olanzapine; conversely, drugs that inhibit CYP1A2 activity (examples: ciprofloxacin, fluvoxamine) may reduce olanzapine clearance.[74] Carbamazepine, a known enzyme inducer, has decreased the concentration/dose ration of olanzapine by 33% compared to olanzapine alone.[73] Another enzyme inducer, ritonavir, has also been shown to decrease the body's exposure to olanzapine, due to its induction of the enzymes CYP1A2 and uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT).[73] Probenecid increases the total exposure (area under the curve) and maximum plasma concentration of olanzapine.[73] Although olanzapine's metabolism includes the minor metabolic pathway of CYP2D6, the presence of the CYP2D6 inhibitor fluoxetine does not have a clinically significant effect on olanzapine's clearance.[73]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Action | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | ≥3,676 | ND | [75][76] | |

| NET | >10,000 | ND | [75] | |

| DAT | >10,000 | ND | [75] | |

| 5-HT1A | 2,063–2,720 | Antagonist | [77][78] | |

| 5-HT1B | 509–660 | ND | [75][78] | |

| 5-HT1D | 540–1,582 | ND | [75][78] | |

| 5-HT1E | 2,010–2,408 | ND | [75][78] | |

| 5-HT1F | 310 | ND | [78] | |

| 5-HT2A | 1.32–24.2 | Inverse agonist | [79][80] | |

| 5-HT2B | 11.8–12.0 | Inverse agonist | [81][82] | |

| 5-HT2C | 6.4–29 | Inverse agonist | [80][82] | |

| 5-HT3 | 202 | Antagonist | [75] | |

| 5-HT5A | 1,212 | Full Agonist | [75] | |

| 5-HT6 | 6.0–42 | Antagonist | [75][83] | |

| 5-HT7 | 105–365 | Antagonist | [75][84] | |

| α1A | 109–115 | Antagonist | [75][77] | |

| α1B | 263 | Antagonist | [75] | |

| α2A | 192–470 | Antagonist | [78][84] | |

| α2B | 82–180 | Antagonist | [77][78] | |

| α2C | 29–210 | Antagonist | [77][78] | |

| β1 | >10,000 | ND | [75][78] | |

| β2 | >10,000 | ND | [75][78] | |

| D1 | 35–118 | Antagonist | [80][84] | |

| D2 | 3.00–106 | Antagonist | [85][86] | |

| D2L | 31–38 | Antagonist | [78][80] | |

| D2S | 21–52 | Antagonist | [78][87] | |

| D3 | 7.8–91 | Antagonist | [85][86] | |

| D4 | 1.6–50 | Antagonist | [85][76] | |

| D4.2 | 17–102 | Antagonist | [88][89] | |

| D4.4 | 21–60 | Antagonist | [87] | |

| D5 | 74–90 | Antagonist | [75][80] | |

| H1 | 0.65–4.9 | Inverse agonist | [75][78] | |

| H2 | 44 | Antagonist | [75] | |

| H3 | 3,713 | Antagonist | [75] | |

| H4 | >10,000 | Antagonist | [75] | |

| M1 | 2.5–73 | Antagonist | [90][91] | |

| M2 | 48–622 | Antagonist | [83] | |

| M3 | 13–126 | Antagonist | [82][83] | |

| M4 | 10–350 | Antagonist | [83][90] | |

| M5 | 6.0–82 | Antagonist | [83][90] | |

| σ1 | >5,000 | ND | [78] | |

| σ2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| Opioid | >10,000 | ND | [78] | |

| nACh | >10,000 | ND | [75] | |

| NMDA (PCP) | >10,000 | ND | [75] | |

| VDCC | >10,000 | ND | [75][78] | |

| VGSC | >5,000 | ND | [78] | |

| hERG | 6,013 | Blocker | [92] | |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. All data are for human cloned proteins, except H3 (guinea pig), σ1 (guinea pig), opioid (rodent), NMDA/PCP (rat), VDCC, and VGSC.[75] | ||||

Olanzapine has a higher affinity for 5-HT2A serotonin receptors than D2 dopamine receptors, which is a common property of most atypical antipsychotics, aside from the benzamide antipsychotics such as amisulpride along with the nonbenzamides aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, blonanserin, cariprazine, melperone, and perospirone.

Olanzapine had the highest affinity of any second-generation antipsychotic towards the P-glycoprotein in one in vitro study.[93] P-glycoprotein transports a myriad of drugs across a number of different biological membranes (found in numerous body systems) including the blood-brain barrier (a semipermeable membrane that filters the contents of blood prior to it reaching the brain); P-GP inhibition could mean that less brain exposure to olanzapine results from this interaction with the P-glycoprotein.[94] A relatively large quantity of commonly encountered foods and medications inhibit P-GP, and pharmaceuticals fairly commonly are either substrates of P-GP, or inhibit its action; both substrates and inhibitors of P-GP effectively increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier to P-GP substrates and subsequently increase the central activity of the substrate, while reducing the local effects on the GI tract. The mediation of olanzapine in the central nervous system by P-GP means that any other substance or drug that interacts with P-GP increases the risk for toxic accumulations of both olanzapine and the other drug.[95]

Olanzapine is a potent antagonist of the muscarinic M3 receptor,[96] which may underlie its diabetogenic side effects.[97][98] Additionally, it also exhibits a relatively low affinity for serotonin 5-HT1, GABAA, beta-adrenergic receptors, and benzodiazepine binding sites.[41][99]

The mode of action of olanzapine's antipsychotic activity is unknown. It may involve antagonism of dopamine and serotonin receptors. Antagonism of dopamine receptors is associated with extrapyramidal effects such as tardive dyskinesia (TD), and with therapeutic effects. Antagonism of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors is associated with anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth and constipation; in addition, it may suppress or reduce the emergence of extrapyramidal effects for the duration of treatment, but it offers no protection against the development of TD. In common with other second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics, olanzapine poses a relatively low risk of extrapyramidal side effects including TD, due to its higher affinity for the 5HT2A receptor over the D2 receptor.[100]

Antagonizing H1 histamine receptors causes sedation and may cause weight gain, although antagonistic actions at serotonin 5-HT2C and dopamine D2 receptors have also been associated with weight gain and appetite stimulation.[101]

Metabolism

Olanzapine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system; principally by isozyme 1A2 (CYP1A2) and to a lesser extent by CYP2D6. By these mechanisms, more than 40% of the oral dose, on average, is removed by the hepatic first-pass effect.[41] Clearance of olanzapine appears to vary by sex; women have roughly 25% lower clearance than men.[73] Clearance of olanzapine also varies by race; in self-identified African Americans or Blacks, olanzapine's clearance was 26% higher.[73] A difference in the clearance does not apparent between individuals identifying as Caucasian, Chinese, or Japanese.[73] Routine, pharmacokinetic monitoring of olanzapine plasma levels is generally unwarranted, though unusual circumstances (e.g. the presence of drug-drug interactions) or a desire to determine if patients are taking their medicine may prompt its use.[73]

Society and culture

Regulatory status

Olanzapine is approved by the US FDA for:

- Treatment—in combination with fluoxetine—of depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder (December 2003).[102]

- Long-term treatment of bipolar I disorder (January 2004).[103][104]

- Long-term treatment—in combination with fluoxetine—of resistant depression (March 2009)[105]

- Oral formulation: acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adults, acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (monotherapy and in combination with lithium or sodium valproate)

- Intramuscular formulation: acute agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar I mania in adults

- Oral formulation combined with fluoxetine: treatment of acute depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults, or treatment of acute, resistant depression in adults[106]

- Treatment of the manifestations of psychotic disorders (September 1996[107] – March 2000).[108]

- Short-term treatment of acute manic episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (March 2000)[108]

- Short-term treatment of schizophrenia instead of the management of the manifestations of psychotic disorders (March 2000)[108]

- Maintaining treatment response in schizophrenic patients who had been stable for about eight weeks and were then followed for a period of up to eight months (November 2000)[108]

The drug became generic in 2011. Sales of Zyprexa in 2008 were $2.2 billion in the US and $4.7 billion worldwide.[109]

Controversy and litigation

Eli Lilly has faced many lawsuits from people who claimed they developed diabetes or other diseases after taking Zyprexa, as well as by various governmental entities, insurance companies, and others. Lilly produced a large number of documents as part of the discovery phase of this litigation, which started in 2004; the documents were ruled to be confidential by a judge and placed under seal, and later themselves became the subject of litigation.[110]

In 2006, Lilly paid $700 million to settle around 8,000 of these lawsuits,[111] and in early 2007, Lilly settled around 18,000 suits for $500 million, which brought the total Lilly had paid to settle suits related to the drug to $1.2 billion.[112][113]

A December 2006 New York Times article based on leaked company documents concluded that the company had engaged in a deliberate effort to downplay olanzapine's side effects.[112][114] The company denied these allegations and stated that the article had been based on cherry-picked documents.[112][113] The documents were provided to the Times by Jim Gottstein, a lawyer who represented mentally ill patients, who obtained them from a doctor, David Egilman, who was serving as an expert consultant on the case.[110] After the documents were leaked to online peer-to-peer, file-sharing networks by Will Hall and others in the psychiatric survivors movement, who obtained copies,[115] in 2007 Lilly filed a protection order to stop the dissemination of some of the documents, which Judge Jack B. Weinstein of the Brooklyn Federal District Court granted. Judge Weinstein also criticized the New York Times reporter, Gottstein, and Egilman in the ruling.[110] The Times of London also received the documents and reported that as early as 1998, Lilly considered the risk of drug-induced obesity to be a "top threat" to Zyprexa sales.[113] On October 9, 2000, senior Lilly research physician Robert Baker noted that an academic advisory board to which he belonged was "quite impressed by the magnitude of weight gain on olanzapine and implications for glucose."[113]

Lilly had threatened Egilman with criminal contempt charges regarding the documents he took and provided to reporters; in September 2007, he agreed to pay Lilly $100,000 in return for the company's agreement to drop the threat of charges.[116]

In September 2008, Judge Weinstein issued an order to make public Lilly's internal documents about the drug in a different suit brought by insurance companies, pension funds, and other payors.[110]

In March 2008, Lilly settled a suit with the state of Alaska,[117] and in October 2008, Lilly agreed to pay $62 million to 32 states and the District of Columbia to settle suits brought under state consumer protection laws.[116]

In 2009, Eli Lilly pleaded guilty to a US federal criminal misdemeanor charge of illegally marketing Zyprexa for off-label use and agreed to pay $1.4 billion. The settlement announcement stated "Eli Lilly admits that between Sept. 1999 and March 31, 2001, the company promoted Zyprexa in elderly populations as treatment for dementia, including Alzheimer’s dementia. Eli Lilly has agreed to pay a $515 million criminal fine and to forfeit an additional $100 million in assets."[118][119]

Trade names

Olanzapine is generic and available under many trade names worldwide.[1]

| A | Aedon, Alonzap, Amulsin, Anzap, Anzatric, Anzorin, Apisco, Apo-Olanzapine, Apo-Olanzapine ODT, Apsico, Arenbil, Arkolamyl |

| B | Benexafrina, Bloonis |

| C | Caprilon, Cap-Tiva, Clingozan |

| D | Deprex, Domus, Dopin |

| E | Egolanza, Elynza, Emzypine, Epilanz-10, Exzapine |

| F | Fontanivio, Fordep |

| G | |

| H | |

| I | Irropia |

| J | Jolyon-MD |

| K | Kozylex |

| L | Lanopin, Lanzapine, Lanzep, Lapenza, Lapozan, Lazap, Lazapir, Lazapix, Lezapin-MD, Lopez |

| M | Marathon, Meflax, Midax, Medizapin |

| N | Niolib, Nodoff, Norpen Oro, Nykob, Nyzol |

| O | Oferta, Oferta-Sanovel, Olace, Oladay, Oladay-F, Olaffar, Olan, Olanap, Olancell, Olandix, Olandoz, Olandus, Olankline, Olanpax, Olanstad, Olanza, Olanza Actavis, Olanza Actavis ODT, Olanzalet, Olanzalux, Olanzamed, Olanzapin 1A Pharma, Olanzapin AbZ, Olanzapin Accord, Olanzapin Actavis, Olanzapin AL, Olanzapin Apotex, Olanzapin Aristo, Olanzapin axcount, Olanzapin beta, Olanzapin Bluefish, Olanzapin Cipla, Olanzapin easypharm, Olanzapin Egis, Olanzapin G.L., Olanzapin Genera, Olanzapin Genericon, Olanzapin Helvepharm, Olanzapin Hennig, Olanzapin Heumann, Olanzapin HEXAL, Olanzapin Krka, Olanzapin Lilly, Olanzapin Mylan, Olanzapin Niolib, Olanzapin Orion, Olanzapin PCD, Olanzapin PharmaS, Olanzapin Ranbaxy, Olanzapin ratiopharm, Olanzapin ReplekFarm, Olanzapin Rth, Olanzapin Sandoz, Olanzapin Spirig HC, Olanzapin Stada, Olanzapin SUN, Olanzapin Teva, Olanzapin Viketo, Olanzapin Zentiva, Olanzapina Accord, Olanzapina Actavis, Olanzapina Actavis PTC, Olanzapina Aldal, Olanzapina Almus, Olanzapina Alter, Olanzapina Angenerico, Olanzapina Anipaz, Olanzapina Apotex, Olanzapina APS, Olanzapina Arrowblue, Olanzapina Aspen, Olanzapina Aurobindo, Olanzapina Basi, Olanzapina Bexalabs, Olanzapina Blixie, Olanzapina Bluefish, Olanzapina Bluepharma, Olanzapina Cantabria, Olanzapina Ceapharma, Olanzapina Ciclum, Olanzapina Cinfa, Olanzapina Cipla, Olanzapina Combix, Olanzapina Doc Generici, Olanzapina Dr. Reddy's, Olanzapina Eulex, Olanzapina Eurogenerici, Olanzapina Fantex, Olanzapina Farmoz, Olanzapina Flas Pharma Combix, Olanzapina Genedec, Olanzapina Generis, Olanzapina Germed, Olanzapina Glenmark, Olanzapina Green Avet, Olanzapina Helm, Olanzapina Kern Pharma, Olanzapina Krka, Olanzapina La Santé, Olanzapina Labesfal, Olanzapina Leugim, Olanzapina Lilly, Olanzapina LPH, Olanzapina Mabo, Olanzapina Medana, Olanzapina Medis, Olanzapina Medley, Olanzapina Mylan, Olanzapina Nakozap, Olanzapina Nolian, Olanzapina Normon, Olanzapina Ozilormar, Olanzapina Parke-Davis, Olanzapina Pensa, Olanzapina Pensa Pharma, Olanzapina Pharmakern, Olanzapina Polipharma, Olanzapina Polpharma, Olanzapina Qualigen, Olanzapina Ranbaxy, Olanzapina Ratio, Olanzapina Ratiopharm, Olanzapina Reconir, Olanzapina Reddy, Olanzapina Rospaw, Olanzapina Sabacur, Olanzapina Sandoz, Olanzapina Sarb, Olanzapina Stada, Olanzapina Sun, Olanzapina TAD, Olanzapina Technigen, Olanzapina Terapia, Olanzapina Teva, Olanzapina Tevagen, Olanzapina tolife, Olanzapina Torrent, Olanzapina Vegal, Olanzapina Vida, Olanzapina Winthrop, Olanzapina Wynn, Olanzapina Kraz, Olanzapina Zentiva, Olanzapina Zerpi, Olanzapina Zonapir, Olanzapin-Actavis, Olanzapin-CT, Olanzapine 1A Pharma, Olanzapine Accord, Olanzapine Actavis, Olanzapine Adamed, Olanzapine Alter, Olanzapine Alvogen, Olanzapine Apotex, Olanzapine Arrow Génériques, Olanzapine Auro, Olanzapine Aurobindo, Olanzapine Biogaran, Olanzapine Bluefish, Olanzapine CF, Olanzapine Clonmel, Olanzapine Cristers, Olanzapine Dexcel, Olanzapine EG, Olanzapine Egis, Olanzapine Evolugen, Olanzapine Galenicum, Olanzapine Generichealth, Olanzapine Glenmark, Olanzapine GSK, Olanzapine Isomed, Olanzapine Jacobsen, Olanzapine Jubilant, Olanzapine Lekam, Olanzapine Lesvi, Olanzapine Medana, Olanzapine Mylan, Olanzapine Neopharma, Olanzapine Niolib, Olanzapine Nyzol, Olanzapine Odis Mylan, Olanzapine ODT Generichealth, Olanzapine ODT Sanis Health, Olanzapine ODT Teva, Olanzapine ODT-DRLA, Olanzapine Orion, Olanzapine Polpharma, Olanzapine Prasco, Olanzapine Ranbaxy, Olanzapine Ratiopharm, Olanzapine Sandoz, Olanzapine Sanis Health, Olanzapine Sanovel, Olanzapine Stada, Olanzapine Sun, Olanzapine Synthon, Olanzapine Teva, Olanzapine Torrent, Olanzapine Zentiva, Olanzapine Zentiva Lab, Olanzapine Zydus, Olanzapine-DRLA, Olzapine |

| P | |

| Q | |

| R | |

| S | |

| T | |

| U | |

| V | |

| W | |

| X | |

| Y | |

| Z | Zyprexa, Zolafren, Zalasta |

Dosage forms

Olanzapine is marketed in a number of countries, with tablets ranging from 2.5 to 20 mg. Zyprexa (and generic olanzapine) is available as an orally disintegrating "wafer", which rapidly dissolves in saliva. It is also available in 10-mg vials for intramuscular injection.[74]

Research

Olanzapine has been studied as an antiemetic, particularly for the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).[120]

In general, olanzapine appears to be about as effective as aprepitant for the prevention of CINV, though some concerns remain for its use in this population. For example, concomitant use of metoclopramide or haloperidol increases the risk for extrapyramidal symptoms. Otherwise, olanzapine appears to be fairly well tolerated for this indication, with somnolence being the most common side effect.[121]

Olanzapine has been considered as part of an early psychosis approach for schizophrenia. The Prevention through Risk Identification, Management, and Education study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and Eli Lilly, tested the hypothesis that olanzapine might prevent the onset of psychosis in people at very high risk for schizophrenia. The study examined 60 patients with prodromal schizophrenia, who were at an estimated risk of 36–54% of developing schizophrenia within a year, and treated half with olanzapine and half with placebo.[122] In this study, patients receiving olanzapine did not have a significantly lower risk of progressing to psychosis. Olanzapine was effective for treating the prodromal symptoms, but was associated with significant weight gain.[123]

References

- Drugs.com Drugs.com international listings for Olanzapine Page accessed August 4, 2015

- Kassahun K, Mattiuz E, Nyhart E, Obermeyer B, Gillespie T, Murphy A, et al. (January 1997). "Disposition and biotransformation of the antipsychotic agent olanzapine in humans". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 25 (1): 81–93. PMID 9010634.

- Callaghan JT, Bergstrom RF, Ptak LR, et al. (September 1999). "Olanzapine: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile". Clin Pharmacokinetics. 37 (3): 177–193. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937030-00001. PMID 10511917.

- Mauri MC, Volonteri LS, Colasanti A, et al. (2007). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of atypical antipsychotics: a critical review of the relationship between plasma concentrations and clinical response". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 46 (5): 359–88. doi:10.2165/00003088-200746050-00001. PMID 17465637. S2CID 43859718.

- "PRODUCT INFORMATION OLANZAPINE SANDOZ® 2.5mg/5mg/7.5mg/10mg/15mg/20mg FILM-COATED TABLETS" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Sandoz Pty Ltd. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Zyprexa, Zyprexa Relprevv (olanzapine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Olanzapine, Olanzapine Pamoate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S (2015). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (12th ed.). London, U K: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-118-75460-3.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Olanzapine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (25 March 2009). "Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- Harvey RC, James AC, Shields GE (January 2016). "A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis to Assess the Relative Efficacy of Antipsychotics for the Treatment of Positive and Negative Symptoms in Early-Onset Schizophrenia". CNS Drugs. 30 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1007/s40263-015-0308-1. PMID 26801655. S2CID 35702889.

- Pagsberg AK, Tarp S, Glintborg D, Stenstrøm AD, Fink-Jensen A, Correll CU, Christensen R (March 2017). "Acute Antipsychotic Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 56 (3): 191–202. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.013. PMID 28219485.

- Osser DN, Roudsari MJ, Manschreck T (2013). "The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on schizophrenia". Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 21 (1): 18–40. doi:10.1097/HRP.0b013e31827fd915. PMID 23656760. S2CID 22523977.

- Duggan L, Fenton M, Rathbone J, Dardennes R, El-Dosoky A, Indran S (April 2005). "Olanzapine for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD001359. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001359.pub2. PMID 15846619.

- Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, Schmid F, Schwarz S, Duggan L, Kissling W, Leucht S (March 2010). "Olanzapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD006654. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006654.pub2. PMC 4169107. PMID 20238348.

- "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Barnes TR (2011). "Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology" (PDF). J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 25 (5): 567–620. doi:10.1177/0269881110391123. PMID 21292923. S2CID 40089561.

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ (2013). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects". World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 14 (1): 2–44. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.739708. PMID 23216388. S2CID 28750563.

- Abou-Setta AM, Mousavi SS, Spooner C, Schouten JR, Pasichnyk D, Armijo-Olivo S, et al. (August 2012). "First-Generation Versus Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Adults: Comparative Effectiveness [Internet]". PMID 23035275. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Zhang JP, Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Malhotra AK, Kane JM, Correll CU (July 2013). "Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 (6): 1205–18. doi:10.1017/S1461145712001277. PMC 3594563. PMID 23199972.

- Citrome L (August 2012). "A systematic review of meta-analyses of the efficacy of oral atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of adult patients with schizophrenia". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 13 (11): 1545–73. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.626769. PMID 21999805. S2CID 23170925.

- Lepping P, Sambhi RS, Whittington R, Lane S, Poole R (May 2011). "Clinical relevance of findings in trials of antipsychotics: systematic review". Br J Psychiatry. 198 (5): 341–5. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075366. PMID 21525517.

- Désaméricq G, Schurhoff F, Meary A, Szöke A, Macquin-Mavier I, Bachoud-Lévi AC, Maison P (February 2014). "Long-term neurocognitive effects of antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 70 (2): 127–34. doi:10.1007/s00228-013-1600-y. PMID 24145817. S2CID 13119694.

- "Bipolar disorder: the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care | 1-recommendations | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O'Donovan C, et al. (December 2006). "Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007". Bipolar Disord. 8 (6): 721–39. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00432.x. PMID 17156158.

- Selle V, Schalkwijk S, Vázquez GH, Baldessarini RJ (March 2014). "Treatments for acute bipolar depression: meta-analyses of placebo-controlled, monotherapy trials of anticonvulsants, lithium and antipsychotics". Pharmacopsychiatry. 47 (2): 43–52. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1363258. PMID 24549862.

- Maglione M, Maher AR, Hu J, et al. (2011). "Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update". AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). PMID 22132426. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Narasimhan M, Bruce TO, Masand P (October 2007). "Review of olanzapine in the management of bipolar disorders". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 3 (5): 579–587. PMC 2656294. PMID 19300587.

- Scott L (Winter 2006). "Genetic and Neurological Factors in Stuttering". Stuttering Foundation of America.

- "Olanzapine and Autism". Research Autism. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Morin AK (March 2014). "Off-label use of atypical antipsychotic agents for treatment of insomnia". Mental Health Clinician. 4 (2): 65–72. doi:10.9740/mhc.n190091.

- Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, Bohlke K, Barbour SY, Clark-Snow RA, et al. (October 2017). "Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 35 (28): 3240–3261. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4789. PMC 4876353. PMID 28759346.

- Taylor D. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Rasmussen SA, Chu SY, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J (June 2008). "Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a metaanalysis". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 198 (6): 611–619. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.021. PMID 18538144.

- McMahon DM, Liu J, Zhang H, Torres ME, Best RG (February 2013). "Maternal obesity, folate intake, and neural tube defects in offspring". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 97 (2): 115–122. doi:10.1002/bdra.23113. PMID 23404872.

- "Important Safety Information for Olanzapine". Zyprexa package insert. Eli Lilly & Company. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death compared to placebo. [...] ZYPREXA (olanzapine) is not approved for the treatment of elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis.

- "Doctors 'ignoring drugs warning'". BBC News. 17 June 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- Yeung EY, Chun S, Douglass A, Lau TE (8 May 2017). "Effect of atypical antipsychotics on body weight in geriatric psychiatric inpatients". SAGE Open Medicine. 5: 2050312117708711. doi:10.1177/2050312117708711. PMC 5431608. PMID 28540050.

- Lexi-Comp Inc. (2010) Lexi-Comp Drug Information Handbook 19th North American Ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp Inc. ISBN 978-1-59195-278-7.

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press http://www.medicinescomplete.com [Accessed on 2 February 2020]

- Stöllberger C, Lutz W, Finsterer J (July 2009). "Heat-related side-effects of neurological and non-neurological medication may increase heatwave fatalities". European Journal of Neurology. 16 (7): 879–82. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02581.x. PMID 19453697. S2CID 25016607.

- "OLANZAPINE (olanzapine) tablet OLANZAPINE (olanzapine) tablet, orally disintegrating [Prasco Laboratories]". DailyMed. Prasco Laboratories. September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Olanzapine 10 mg tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Aurobindo Pharma - Milpharm Ltd. 17 May 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Olanzapine Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Cerner Multum Incorporated (27 September 2011). "Olanzapine". Drugs.com.

- Alevizos, Basil; Papageorgiou, Charalambos; Christodoulou, George N. (1 September 2004). "Obsessive-compulsive symptoms with olanzapine". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 7 (3): 375–377. doi:10.1017/S1461145704004456. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 15231024.

- Kulkarni, Gajanan; Narayanaswamy, Janardhanan C.; Math, Suresh Bada (1 January 2012). "Olanzapine induced de-novo obsessive compulsive disorder in a patient with schizophrenia". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 44 (5): 649–650. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.100406. ISSN 0253-7613. PMC 3480803. PMID 23112432.

- Lykouras, L.; Zervas, I. M.; Gournellis, R.; Malliori, M.; Rabavilas, A. (1 September 2000). "Olanzapine and obsessive-compulsive symptoms". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (5): 385–387. doi:10.1016/s0924-977x(00)00096-1. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 10974610. S2CID 276209.

- Schirmbeck, Frederike; Zink, Mathias (1 March 2012). "Clozapine-Induced Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Critical Review". Current Neuropharmacology. 10 (1): 88–95. doi:10.2174/157015912799362724. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 3286851. PMID 22942882.

- Ramankutty G (2002). "Olanzapine-induced destabilization of diabetes in the absence of weight gain". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 105 (3): 235–6, discussion 236–7. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.2c257a.x. PMID 11939979. S2CID 5965031.

- Lambert MT, Copeland LA, Sampson N, Duffy SA (2006). "New-onset type-2 diabetes associated with atypical antipsychotic medications". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 30 (5): 919–23. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.02.007. PMID 16581171. S2CID 24739534.

- Moyer P (25 October 2005). "CAFE Study Shows Varying Benefits Among Atypical Antipsychotics". Medscape Medical News. WebMD. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (4 April 2006). "Efficacy and Tolerability of Olanzapine, Quetiapine and Risperidone in the Treatment of First Episode Psychosis: A Randomised Double Blind 52 Week Comparison". AstraZeneca Clinical Trials. AstraZeneca PLC. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

At week 12, the olanzapine-treated group had more weight gain, a higher increase in [ body mass index ], and a higher proportion of patients with a BMI increase of at least 1 unit compared with the quetiapine and risperidone groups (p<=0.01).

- Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, Berisford MA, Goldstein D, Pashdag J, Mintz J, Marder SR (1999). "Novel Antipsychotics". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (6): 358–63. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0602. PMID 10401912.

- "NIMH study to guide treatment choices for schizophrenia" (Press release). National Institute of Mental Health. 19 September 2005. Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, Hamer RM, Gu H, Lazarus A, Sweitzer D, Olexy C, Weiden P, Strakowski SD (July 2007). "Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (7): 1050–60. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1050. PMID 17606657.

- Nemeroff CB (1997). "Dosing the antipsychotic medication olanzapine". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 Suppl 10 (Suppl 10): 45–9. PMID 9265916.

- Fulbright AR, Breedlove KT (2006). "Complete Resolution of Olanzapine-Induced Diabetic Ketoacidosis". Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 19 (4): 255–8. doi:10.1177/0897190006294180. S2CID 73047103.

- Chiu CC, Chen CH, Chen BY, Yu SH, Lu ML (August 2010). "The time-dependent change of insulin secretion in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 34 (6): 866–70. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.003. PMID 20394794. S2CID 22445875.

- Sacher J, Mossaheb N, Spindelegger C, Klein N, Geiss-Granadia T, Sauermann R, Lackner E, Joukhadar C, Müller M, Kasper S (June 2008). "Effects of olanzapine and ziprasidone on glucose tolerance in healthy volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (7): 1633–41. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301541. PMID 17712347.

- Sowell M, Mukhopadhyay N, Cavazzoni P, Carlson C, Mudaliar S, Chinnapongse S, Ray A, Davis T, Breier A, Henry RR, Dananberg J (December 2003). "Evaluation of insulin sensitivity in healthy volunteers treated with olanzapine, risperidone, or placebo: a prospective, randomized study using the two-step hyperinsulinemic, euglycemic clamp". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 88 (12): 5875–80. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021884. PMID 14671184.

- Carey B (20 September 2005). "Little Difference Found in Schizophrenia Drugs". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- de Haan L, van Amelsvoort T, Rosien K, Linszen D (2004). "Weight loss after switching from conventional olanzapine tablets to orally disintegrating olanzapine tablets". Psychopharmacology. 175 (3): 389–90. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1951-2. PMID 15322727. S2CID 38751442.

- Luedecke D, Schöttle D, Karow A, Lambert M, Naber D (January 2015). "Post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome in patients treated with olanzapine pamoate: mechanism, incidence, and management". CNS Drugs. 29 (1): 41–6. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0216-9. PMID 25424243. S2CID 10928442.

- Brambilla G, Mattioli F, Martelli A (2009). "Genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of antipsychotics and antidepressants". Toxicology. 261 (3): 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2009.04.056. PMID 19410629.

- Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- Haddad P, Haddad PM, Dursun S, Deakin B (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. pp. 207–216. ISBN 9780198527480.

- Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655. S2CID 6267180.

- Sacchetti E, Vita A, Siracusano A, Fleischhacker W (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797.

- "Symbyax (Olanzapine and fluoxetine) drug overdose and contraindication information". RxList: The Internet Drug Index. WebMD. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- Schwenger E, Dumontet J, Ensom MH (July 2011). "Does olanzapine warrant clinical pharmacokinetic monitoring in schizophrenia?". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 50 (7): 415–28. doi:10.2165/11587240-000000000-00000. PMID 21651311. S2CID 21097041.

- "Olanzapine Prescribing Information" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Ablordeppey SY, Altundas R, Bricker B, Zhu XY, Kumar EV, Jackson T, Khan A, Roth BL (2008). "Identification of a butyrophenone analog as a potential atypical antipsychotic agent: 4-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,4-diazepan-1-yl]-1-(4-fluorophenyl)butan-1-one". Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16 (15): 7291–301. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.06.030. PMC 2664318. PMID 18595716.

- Kroeze WK, Hufeisen SJ, Popadak BA, Renock SM, Steinberg S, Ernsberger P, Jayathilake K, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (2003). "H1-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (3): 519–26. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300027. PMID 12629531.

- Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, Luyten WH, Van Gompel P, Lesage AS, De Loore K, Leysen JE (1996). "Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding". Psychopharmacology. 124 (1–2): 57–73. doi:10.1007/bf02245606. PMID 8935801. S2CID 12028979.

- Davies MA, Setola V, Strachan RT, Sheffler DJ, Salay E, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL (2006). "Pharmacologic analysis of non-synonymous coding h5-HT2A SNPs reveals alterations in atypical antipsychotic and agonist efficacies". Pharmacogenomics J. 6 (1): 42–51. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500342. PMID 16314884.

- Kongsamut S, Roehr JE, Cai J, Hartman HB, Weissensee P, Kerman LL, Tang L, Sandrasagra A (1996). "Iloperidone binding to human and rat dopamine and 5-HT receptors". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 317 (2–3): 417–23. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00840-0. PMID 8997630.

- Wainscott DB, Lucaites VL, Kursar JD, Baez M, Nelson DL (1996). "Pharmacologic characterization of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine2B receptor: evidence for species differences". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 276 (2): 720–7. PMID 8632342.

- Bymaster FP, Nelson DL, DeLapp NW, Falcone JF, Eckols K, Truex LL, Foreman MM, Lucaites VL, Calligaro DO (1999). "Antagonism by olanzapine of dopamine D1, serotonin2, muscarinic, histamine H1 and alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in vitro". Schizophr. Res. 37 (1): 107–22. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00146-7. PMID 10227113. S2CID 19891653.

- Bymaster FP, Felder CC, Tzavara E, Nomikos GG, Calligaro DO, Mckinzie DL (2003). "Muscarinic mechanisms of antipsychotic atypicality". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 27 (7): 1125–43. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.008. PMID 14642972. S2CID 28536368.

- Fernández J, Alonso JM, Andrés JI, Cid JM, Díaz A, Iturrino L, Gil P, Megens A, Sipido VK, Trabanco AA (2005). "Discovery of new tetracyclic tetrahydrofuran derivatives as potential broad-spectrum psychotropic agents". J. Med. Chem. 48 (6): 1709–12. doi:10.1021/jm049632c. PMID 15771415.

- Seeman P, Tallerico T (1998). "Antipsychotic drugs which elicit little or no parkinsonism bind more loosely than dopamine to brain D2 receptors, yet occupy high levels of these receptors". Mol. Psychiatry. 3 (2): 123–34. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000336. PMID 9577836.

- Burstein ES, Ma J, Wong S, Gao Y, Pham E, Knapp AE, Nash NR, Olsson R, Davis RE, Hacksell U, Weiner DM, Brann MR (2005). "Intrinsic efficacy of antipsychotics at human D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors: identification of the clozapine metabolite N-desmethylclozapine as a D2/D3 partial agonist". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315 (3): 1278–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.092155. PMID 16135699. S2CID 2247093.

- Seeman P, Van Tol HH (1995). "Deriving the therapeutic concentrations for clozapine and haloperidol: the apparent dissociation constant of a neuroleptic at the dopamine D2 or D4 receptor varies with the affinity of the competing radioligand". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 291 (2): 59–66. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(95)90125-6. PMID 8566176.

- Arnt J, Skarsfeldt T (1998). "Do novel antipsychotics have similar pharmacological characteristics? A review of the evidence". Neuropsychopharmacology. 18 (2): 63–101. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00112-7. PMID 9430133.

- Tallman JF, Primus RJ, Brodbeck R, Cornfield L, Meade R, Woodruff K, Ross P, Thurkauf A, Gallager DW (1997). "I. NGD 94-1: identification of a novel, high-affinity antagonist at the human dopamine D4 receptor". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 282 (2): 1011–9. PMID 9262370.

- Bymaster FP, Calligaro DO, Falcone JF, Marsh RD, Moore NA, Tye NC, Seeman P, Wong DT (1996). "Radioreceptor binding profile of the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine". Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(94)00129-N. PMID 8822531.

- Bymaster FP, Falcone JF (2000). "Decreased binding affinity of olanzapine and clozapine for human muscarinic receptors in intact clonal cells in physiological medium". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 390 (3): 245–8. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00037-6. PMID 10708730.

- Kongsamut S, Kang J, Chen XL, Roehr J, Rampe D (2002). "A comparison of the receptor binding and HERG channel affinities for a series of antipsychotic drugs". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 450 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02074-5. PMID 12176106.

- Wang JS, Zhu HJ, Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL (September 2006). "Evaluation of antipsychotic drugs as inhibitors of multidrug resistance transporter P-glycoprotein". Psychopharmacology. 187 (4): 415–423. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0437-9. PMID 16810505. S2CID 13365903.

- Moons T, de Roo M, Claes S, Dom G (August 2011). "Relationship between P-glycoprotein and second-generation antipsychotics". Pharmacogenomics. 12 (8): 1193–1211. doi:10.2217/pgs.11.55. PMID 21843066.

- Horn JR, Hansten P (1 December 2008). "Drug Transporters: The Final Frontier for Drug Interactions". Pharmacy Times.

- Johnson DE, Yamazaki H, Ward KM, Schmidt AW, Lebel WS, Treadway JL, Gibbs EM, Zawalich WS, Rollema H (2005). "Inhibitory Effects of Antipsychotics on Carbachol-Enhanced Insulin Secretion from Perifused Rat Islets: Role of Muscarinic Antagonism in Antipsychotic-Induced Diabetes and Hyperglycemia". Diabetes. 54 (5): 1552–8. doi:10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1552. PMID 15855345.

- Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Deng C (10 October 2013). "Second Generation Antipsychotic-Induced Type 2 Diabetes: A Role for the Muscarinic M3 Receptor". CNS Drugs. 27 (12): 1069–1080. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0115-5. PMID 24114586. S2CID 5133679.

- Silvestre JS, Prous J (2005). "Research on adverse drug events. I. Muscarinic M3 receptor binding affinity could predict the risk of antipsychotics to induce type 2 diabetes". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (5): 289–304. doi:10.1358/mf.2005.27.5.908643. PMID 16082416.

- "olanzapine". NCI Drug Dictionary. National Cancer Institute. 2 February 2011.

- Lemke TL, Williams DA (2009) Foye's Medicinal Chemistry, 6th edition. Wolters Kluwer: New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-89960-30-8.

- Wallace TJ, Zai CC, Brandl EJ, Müller DJ (18 August 2011). "Role of 5-HT(2C) receptor gene variants in antipsychotic-induced weight gain". Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine. 4: 83–93. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S11866. PMC 3513221. PMID 23226055.

- "NDA 21-520" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 24 December 2003. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- "NDA 20-592 / S-019" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 14 January 2004. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- Pillarella J, Higashi A, Alexander GC, Conti R (2012). "Trends in Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotics for Treatment of Bipolar Disorder in the United States, 1998–2009". Psychiatric Services. 63 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100092. PMC 4594841. PMID 22227765.

- Bobo WV, Shelton RC (2009). "Olanzapine and fluoxetine combination therapy for treatment-resistant depression: review of efficacy, safety, and study design issues". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 5: 369–83. doi:10.2147/NDT.S5819. PMC 2706569. PMID 19590732.

- treatment resistant depression defined as major depressive disorder in adult patients who do not respond to two separate trials of different antidepressants of adequate dose and duration in the current episode

- "NDA 20-592" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. 6 September 1996. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- "Eli Lilly and Company Agrees to Pay $1.415 Billion to Resolve Allegations of Off-label Promotion of Zyprexa". U.S. Justice Department. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Lilly 2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Lilly. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- Walsh MW (5 September 2008). "Judge to Unseal Documents on the Eli Lilly Drug Zyprexa". The New York Times.

- Berenson A (4 January 2007). "Mother Wonders if Psychosis Drug Helped Kill Son". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Berenson A (5 January 2007). "Lilly Settles With 18,000 Over Zyprexa". The New York Times.

- Pagnamenta, Robin (23 January 2007). "Eli Lilly was concerned by Zyprexa side-effects from 1998". The Times (London). Archived from the original on 20 February 2007.

- Berenson A (17 December 2006). "Eli Lilly Said to Play Down Risk of Top Pill". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Ashton K (16 January 2007). "Activist Gagged for Drug Fact Leak in Lily Case" (PDF). Hampshire Daily Gazette.

- Harris G, Berenson A (14 January 2009). "Lilly Said to Be Near $1.4 Billion U.S. Settlement". The New York Times.

- Berenson A (26 March 2008). "Lilly Settles Alaska Suit Over Zyprexa". The New York Times.

- "Lilly settles Zyprexa suit for $1.42 billion". NBCNews.com. Associated Press. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021.

- Berenson A (18 December 2006). "Drug Files Show Maker Promoted Unapproved Use". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Sutherland, Anna; Naessens, Katrien; Plugge, Emma; Ware, Lynda; Head, Karen; Burton, Martin J.; Wee, Bee (21 September 2018). "Olanzapine for the prevention and treatment of cancer-related nausea and vomiting in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD012555. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012555.pub2. PMC 6513437. PMID 30246876.

- Schwartzberg L (March 2018). "Getting it right the first time: recent progress in optimizing antiemetic usage". Supportive Care in Cancer. 26 (Suppl 1): 19–27. doi:10.1007/s00520-018-4116-2. PMC 5876255. PMID 29556812.

- McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller TJ, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman R, Lindborg S, Tohen M, Breier A (2003). "The PRIME North America randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis". Schizophrenia Research. 61 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00439-5. PMID 12648731. S2CID 1118339.

- McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, Addington J, Miller T, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, Hoffman RE, Preda A, Epstein I, Addington D, Lindborg S, Trzaskoma Q, Tohen M, Breier A (2006). "Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Olanzapine Versus Placebo in Patients Prodromally Symptomatic for Psychosis". American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (5): 790–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.790. PMID 16648318.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olanzapine. |

- "Olanzapine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Berenson A (5 January 2007). "Lilly Settles With 18,000 Over Zyprexa". The New York Times.